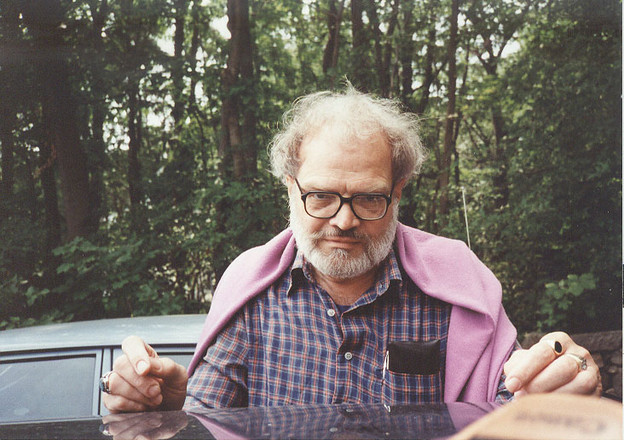

Kenneth Irby's homecoming

To read Kenneth Irby is to experience the attentive gestures of perceptive life. As he observes (via Sir Thomas Browne): “To live indeed is to be again our selves … Ready to be any thing, in the extasie of being ever.” Carl O. Sauer’s geographic and cultural sense of morphology informs the complex spiritual depth in Irby’s lucid writing. He is preoccupied with lands that have insisted on my attention, too: Texas, Kansas, New Mexico, California; so for me to read his poetry invites a sympathetic and friendly perspective, one constructed adjacently on the plains of the Midwest. A spiritual geography takes shape through the pressures of attention he gives to these regions. A body of love is extended by habits of perception, renewing affection for place through the careful pursuit of a feeling mind.

Irby’s writing, moreover, attempts to conjoin the visible and invisible terrains that confront him. A narrative adheres in the lyric accumulation of his art to reveal the dispersed self in words, something located beyond memory and beyond action. His art contributes a narrative of creative imaginings, advancing what Kenneth Burke once called a qualitative progression of formal appeal.[1] Such arrangements are dispersed through echoes, returns, incongruent ruptures, restatements of key themes, paradoxes, and variances in the incremental movements that give art adherence, its present tense. While Irby’s work has appeared in small editions over several decades, the effect of reading The Intent On: Collected Poems 1962–2006 (2009) is like encountering a major symphonic event (the inspired romanticism of Frederick Delius informs with lush splendor the qualitative movement of the serial sequences here).

Irby upholds Charles Olson’s consideration of geography and North American space; Edward Dorn’s sense of the West as divided topography; Robert Duncan’s attention to spiritual depths and correspondences; Walt Whitman’s body of feeling as sexual gateway; and Nerval’s romanticizing power. While he draws on these figures to enable his art, Irby’s writing is devoted also to a body of feeling that is uniquely his own, one that attempts again and again to register the depth of home or homecoming “across the gap,” between phenomenal experience and the imagined realities superimposed on the sensuous textures of place. Throughout the restless search arranged in the body of his work, there is a primary sense of place as homeward recognition and recall in the variant pulsations of life.

Major themes, literary and geographic resonances, and proprioceptive acknowledgments were discussed in regards to Irby’s work by 1979. That year Robert J. Bertholf’s journal Credences devoted an issue to Irby’s writing. The biographic, textual, and historic particulars of the early poems are addressed with enthusiasm by luminaries of the period like Don Byrd, Thomas Meyer, Jed Rasula, Theodore Enslin, Robert Kelly, and others.[2] For me now, 1979 stands out as a moment of the beginning of closure for the openness and investigations of the 1960s. Within a year Ronald Reagan would begin extending the dollar sign over everything, and a new pacing in poetic temperament in the US would start to take place, shifting emphasis away from the New American writing so firmly articulated with Donald Allen’s seminal anthology. Instead, a preference for the terms of the academy and the creative writing workshop would displace the expansive and speculative approaches seen in Normon O. Brown, Henry Corbin, Sherman Paul, and others who influenced much of the writing of the 1970s.

The forms of serial poetry initiated by Robert Duncan and Jack Spicer, and notably taken up by Michael Palmer, Susan Howe, Ted Enslin, Irby, and others, would settle into a literary background largely informed instead by the mashup of linguistic and cultural themes taken up in Language Poetry. 1979 was a gateway year, pivoting between the hippie, open experience of Kerouac’s road and a new institutionalized order of experience. But this, too, is an illusion, as all attempts to measure cultural value ultimately strand the argument in the limited perspective of the critic. Recall, for instance, Robert Duncan’s description of how Pound’s renewal of the image of Persephone was articulated as a cultural figure significant to that particular milieu in the early decades of the last century.[3] Each generation takes from the previous necessary tropes and concerns. If Madam Blavatsky and the Order of the Golden Dawn influenced 1909 London and Paris the way Zizek has been distilled for us today, we begin to see how cultural motives are absorbed, traced, retracked, and finally abandoned for other concerns. Irby’s work straddles literary attention to the cultural geography associated with Black Mountain while also being pressured by the motives of a new era of cultural concern. More importantly, his writing is situated with resolve among the ravines, hillocks, fence posts, and skies of the West. If, as Guy Davenport argues, Pound used the Cantos to build a city “as the one clear conquest of civilization,” and Olson searched for home in the spiritual remains of Gloucester, Irby actualizes the open field, casting a watchful eye on the urban penetration and civil conquests of the rural West. He defines his poetics outside the city walls in fields of wheat and sunflower.

Irby’s writing after 1979 continues to trace the morphology of the continent established in books like Kansas–New Mexico, Relations, To Max Douglas, and Catalpa, but the qualitative progression of form registers new critical perspectives. Ridge to Ridge (Poems 1990–2000) takes place over a decade with the serial formality established in prior work, and attention correlates a body of love to the morphology of a landscape infused with personal narrative.[4] Generally, the longer lines establish a thoughtful inquiry that attempts to narrow the distance between self and reality in a poetic language of homecoming. Surprisingly, however, Ridge to Ridge opens with an untitled section, establishing perspective from an interior hearth rather than the wider vistas suggested by the book’s title:

a life into a few vegetables set in a half-shadowed deep window frame

black dirt gloss across flame orange carrots, ivory sprouted filaments from

upcurved fennel and cardoon stalks

how long to sit there to be seen into the painting

how long the lemon cut before glazed over, and another

but in the words past the breeze through from the bedroom window up the

short hall to the feet, and through again (523)

The opening still life frames the poem, showing perspective of landscape narrowed to the window box garden in an almost ironic relationship to the larger geographic vistas of previous work. But these lines determine Irby’s concern also for the poem, for poetry and physical geography finally intersect in the affectionate correspondence of creative imaginings. In the following serial segment a question brings this firmly to light: “how far away do you have to be to see, to be able finally to hear / the poem / and of nobility in what is lost” (523)? The concerns in Ridge to Ridge largely consider this problem of perspective. Self-imposed distances, spiritual yearning and isolation, and the shamanic barter of social negotiations are all suggested as processes in Irby’s engagement with art. Poetry in this sense becomes a tool to reveal many kinds of perspectives, including visions of the self, the landscape, and the queer morphologies of a sublimated sexual knowledge.

The longing of sensuous desire is perhaps heard in the yearning song of the sailor in the Spanish ballad, “Romance de Conde Amaldos”: “cry out to the sailor who is singing it, ‘o tell it to me, tell it to me, please!’ / but he but only answers, ‘o no, this song I only tell to him who with me goes’ / / yo no digo esta canción / sino a quien conmigo va” (523). Sexuality is expressed as dynamic energy shared by those who are willing to take risks, to “him who with me goes.” The soul, expressed as the tension of singer and auditor in the ballad, activates sexual correspondence with the body, announced as “a gesture” that “is elsewhere than the palace of administration.” In Irby’s art, the power of imagination swells and consumes the nature of the poet, requiring an attention alien to administrative forms. It is a kind of shelter:

here there is a butterfly in the knowing of that shelter that would return

to change but being there together

ascent by ink and in the black ground black hidden metallic lusters

up out of each stroke of the pen (524)

The “stroke of the pen” into the “black ground black” suggests an erotic charge of energy required in the kind of active love Irby’s imagination requires. The longing for spiritual companionship finds determining forms in an “ascent by ink.” Sexuality is not confined to genital fucking, but pulses as creative urgency across time and distance. The erotic expression is adhesive, shaped by Olson’s sexually evoked notion of energy in the composition methods of “Projective Verse”: The poem for Olson, as for Irby, must “be a high energy-construct and, at all points, an energy-discharge.”[3] The sexually descriptive account, with masculine pressure, reconnects Whitman’s amative aims in Leaves of Grass through a more aggressive and comprehensive totality of sexual potential. Male sensual energy, while not overtly presented by Irby, registers in the descriptive urgency of his dynamic and active engagement with the formal “bodies” of his poems.

The final stanza shifts gears dramatically in a qualitative progression, abandoning the long flowing lines of creative search in favor of more compact statements. A turn to memory restores the poet’s equilibrium, grounding Irby’s resources in imagination’s twin. Imagination and memory correspond with perception and history, internalized potentials in the self as they are transacted on the formal features of geographic terrain. Irby writes:

some high new tangerine wax fancy

or pink fluorescent twin of deep lament

of children’s coloring book on through a lifetime yet

bright warm clothes that are a rug to the empyrean

elytron opened through the solid trunk of driven sheet

wrapped close and then passed on

there could not be without that fancy now

that indirection of embellishment

to be most dignity and testament

crows take the crows take the over

to teach us insufficiency

heart-wrap skin to call exultant austerity

and spring open a redbird drop cut

tierce tierce tierce tierce tierce (524)

Here the earlier “nobility in what is lost” (523) is echoed by the “dignity and testament” of ancient knowledge, a corvine pedagogy based in certain Native American traditions where the figure of crow is that of the shape-shifter, keeper of ancient laws and folkways. Crow is believed to be guide to the supernatural, and so Irby’s concern here reveals a geographically focused intent on spiritual pathways through the calling forth of local figures of transformation. The “bright warm clothes” that barter passage to “empyrean” are terrestrially figured in the “elytron,” or shard, the hard insect wing that rhymes with the crow wings and redbird wings of spring. The “bright clothes” recall the “heart-wrap skin,” and so the formal relationships continually establish echoes in morphology of self-transformation. The final line, too, persists in aligning the spiritual with the animal (tierce is the third of seven canonical hours), dallying in the metaphoric calls of birds.

If perspective comes framed by a window in the opening poem sequence, “[vistas, over Lammas]” begins “down in the furrow” (525) — a harvest poem concerned with “measuring, across the gap” (526). Relations of earth and sky, continental migration, gender and family, genital grasping, art and administration (again) provide the primary thematic structure, but the poem’s incidental form largely coheres through metaphoric claims of a vision of late summer. The human body and the landscape are established in an abiding relationship, and in the narrative of the poem a magus figure appears in an active space of “grass walk heart.” An image of a writer appears on “the land behind the ruined barn … scarring the knees and shins, spattering ink on the knuckles, leaving sores on the wrist to time” (525). The poet-magus observes “the field’s body” beside that of

the last Bard, the last mantic poet, possessor of the secret, shared, and

essential history of the whole tradition and its magic

driven to the highest crag above the brilliant torrent of the boundary

time crack raging between the worlds, sunset grandeur of cataclysm

sweeping the cloudscape away behind

at bay defies the invading army come to exterminate all the Makers

into the disappearance

lost (525)

This figure of the Time Visionary (“possessor of the secret”) “defies the invading army” of “the palace of administration” (523), a metonymic value cast largely over systemic forms of thought, economy, and order that contrive for the disappearance of the “essential history” possessed by the “last Bard.” This figure presides later in the poem “by the light of the full moon and the stars of the Big Dipper,” in “the commune of workers in the field of vision, in the field of making” (526). Measurement “across the gap” (against “the torrent of the boundary”) later “opens to the Islands of the Blessed and Beyond the Blessed” (525). Such attention to measurement assures that “it is not lost” in the exterminating forms of administration attempting to arrest the mind of the magus-poet. The bardic claim persists in the visionary corpus of sensual America established by Whitman, but Irby’s sense of authority is presented differently. It’s not the bardic figure who controls “the secret,” but who establishes its relation instead in almost seasonal form as witness to the bodies of the earth. Knowledge of the secret adheres by “the month of the mother” and “the month of the father,” in a “measuring, across the gap” (525). Whitman’s construction of a “bardic ethos” in Leaves of Grass requires the assent of an audience in recognizing the poet as essential holder of wisdom.[4] Irby, however, acknowledges bardic responsibility in the sensuous measurements and observations that are built on perspectives of witness and active creative participation. The dramatic difference in poetic conception ensures Irby’s gifts of coequal engagement with a world determined by his affinities for the open spaces of the West, and it spares him of the Whitmanic role of possessor of visionary power. In other words, Irby values an active participation in the creative topography of his landscape, whereas for Whitman, the power of utterance determines and orders a perverse asymmetry between poetic vision and the experience of reading in submission to the extraordinary and distant bard. Irby humanizes the role of poet while also determining new possibilities of bardic revelation.

The qualitative progression of the poem also disrupts bardic authority, inviting readings that appeal formally through an incongruent extension of terms that organize narrative according to key clusters of imagery. “[H]istory,” “tradition,” and “magic” are modified by “the highest crag,” establishing narrative through contrasts of form and symbolic relations that activate the “sunset grandeur of cataclysm.” Narrative form progresses for Irby through contrasts and sudden enjambed features of a poetic topography that finds its greatest expression in metaphoric statements and revisions. We therefore see the active form here as a series of possible motives or developments that bring satisfaction through the accumulating and shifting features that the poem generates as its own narrative engine.

Since Irby does not overstate the importance of the bardic seer, he’s better able to examine the cyclic wobble of earth’s forces, attending the morphological coherences that inform his work from the beginning. He moves from the cosmological argument of the poem to a sensuous description of a “young man barechested holding the surveyor’s rod” (525). And he goes “beyond the mown enfolded hayfield lined up with the telephone pole” and “disappears behind the lone / monumental sumac.” While the poem sequence opens with anxious quest on behalf of the bardic figure, the landscape and its inhabitants (and its imaginary orderings) are preserved in “body clasping body, across the gap.” These gaps are by nature everywhere in the landscape, but through love bodies reach out to bridge the inevitable distances. At stake there appears to be a resistance to the death of administration, the certainty of colossal separation. But it is also a significant recognition of the body of imagination, the creative “clasping” for the other in all its forms. The humble and humane figure of the bard seeks connection through form; he does not dominate it or the reader, but invites us to perceive according to an advanced stride in the measures of topographic and spiritual “gaps” unforeseen. It is “the heart’s seed” that concerns him, and he presents this seminal figure along, once again, with crows:

what can be known of the heart any more than of the colloquy of the

crows in the field out the window

three in a great triangle, walking

and one flown away, and returned, and their calling

or now in the root crease of the field, where they gather and glean

the heart’s seed

not lost (527)

These talismanic figures of the poem initiate the gathering and gleaning of “the heart’s seed.” They are animistic features that distill the earnest reaching of the bard within the frame of perception that gives form adherence. The poet is shape shifter, coordinated in animistic relations with land and beast. Crows, as birds holding the secrets, correlate with the notion of poet as gatekeeper, or minder of the gaps, initiating possibility through the gestures of affection performed for the apprehension of concerned readers. As the avian familiar of Odin, crows also relate to the poet as seer in Nordic traditions. The significance of these birds for Irby in this poem illustrates the kind of metaphoric threading or comparisons by relation important to his art.

The qualitative appeal of Irby’s serial writing is also in large part due to the sheer delight in language and the variation of rhythms and rhymes (or off-rhymes) he presents in a kind of jazz improv, where mind and ear conjoin into active participation. For instance, this stanza from “[to almost midnight New Year’s Eve in Glasgow]” opens a sequence where the imaginative process of memory is disclosed as poetic form in a startling sequence dense yet jubilant in its arcs. The poem begins:

into the dark before the dark before the years

the old pants’ velour touch, to the new unknown belongs

as if there were no grown set worry and no undressing out enough

old skin leopard teddy bear witchery of variations memory

and the hat even the feather tango

each nut each sip a look into the ear

incapable smartness, unpredictable calling

old cold metal tumbler the wet lip just sticks to

Coca Cola Lifesavers from before the war accrual

and that soft mezza voce tuba languor and arousal

in the rapt aphasic ear (529)

The enveloping darkness prior to one’s being (“the years”) correlates the “new unknown,” breaking out of the “heart wrap skin” (524) that here becomes “old skin leopard teddy bear witchery of variations of memory.” The sequence, with its abrupt shifts and surprising turns, metaphoric density, and rhythmic aplomb, initiates witness of the self as something that coheres in the forms and images (symbolic forces) that testify through the (often fuzzy) recall of memory. The process activates as “unpredictable calling,” and in the language of the poem, with its symbolic densities and formal progressions, a semblance of what a self might be comes into a new kind of being. The projective elements here certainly recall Olson’s sense of projective verse, where the mind and the body like a jazz musician unite in quick, temperamental pursuits of “the new unknown,” to make it, not, perhaps, known, but activated as spiritual action.

Much of the work in Ridge to Ridge tries to address these dense relations of form through the image of home. The memories worked up into a present tense in the poem activate a sense of home as the accumulation of what is willed into the present through memory. If what we know is wound through a vortex of experience, sensory pulses, applied uses of culture and its forms of language, what coheres as home — as our own? I’m not talking about an ownership as identity — but as spiritual revelation of the common terms of our humanity. Whether it’s Pound’s Wagadu, the Soninke legendary city existing only in the heart, or Olson’s figure of the man with a house on his head, the notion of home retains for Irby a primary feature of identity and process. To see “ridge to ridge” or vista-by-vista is to be constantly active in attention to horizons that come into view and pass away. The past experiences of self arrive and then fade as time frames our passages through diverse situations. For Irby, personal experience is prior to one’s life advancing as creative form, and so home is also homage, an engagement with the distant figures of the imagination that composes the far vista of one’s being. Speaking of Mayan culture and the relationships that adhere across time, Irby recalls observations by Sauer of the centrality of corn, beans, and squash to the ancient diet of the Americas. But this leads him to consider Mayan forms of play, which open up a sense of play in his own “obligation to sustain” as poet-maker:

day care to high school to nursing home, the central corn stalk on the hill

of beans and squash

with its fish and seed, up the spinal column of the hemisphere, the ball

game of the continents

where the directions mesh in play, hole and ear, fiber and hair

become first concert

what play, to be consulted on?

the old grande dame of silk and wool, first dancer once, choreographer of

the lost Pinar once

teacher in the continuance, sun-to-come-up necessary dance with that

same necessary song

a child inherits and knows the obligation to sustain, homage

questions, have you?

between the reflections in the water and the incessant tremor, the short

sharp intake of breath at each intensity

each scarred knuckle smeared the same ecstatic shine (530)

The “dance” and “song” of intercultural, interpersonal progression sustain homage in the “ecstatic shine” of the artist’s visionary intensity. The insistence on vision as the inheritance of lore, dance, and song lets Irby transmit a sense of place as wholly fused with the intent on observation and willful action in the art of attention. The moral obligation of the artist, Irby suggests, is to perform with creative skill and discipline so that a world may be known in the play of its forms. Otherwise, there is no homecoming, no perception of the complex inherence that competes for attention in the process of what we call a world. Without instruments of dance, song, or play, we are limited to imposed claims of what our place in a world can be. Irby continues:

what makes you think you are not in prose because you do not know the

continuity?

it is not melancholy, it is not sadness, it is not lament, but the shape and

trace of distance

is that release? is that what the concern is about homecoming, about

what home is? itself homage

where some kids have never seen an instrument to play at all, and some

adults never known the means of their production

the black ungained bottom of their unexceptioned conjugal necessity

angel (530)

Home is “homecoming,” a return from “the shape and trace of distance,” one’s own unwinding into the spiritual forms through which life takes shape. An invisible morphology runs parallel to that of the visible geographic and cultural morphologies. While these themes appear in earlier books, the critical gesture of the 1990s is to speak with greater frequency about what is risked in homecoming, and the larger failures of neglecting home as the symbolic frequency of one’s arrival into self-awareness. Such an account of homecoming is shoved by “memory’s emptiness / how space and time bulge with so much wanting of / until it is whatever direction is, direction as, directionless / except not-here, except all-here” (531). He speaks of a “cultivation impossible to cultivate,” acknowledging that “memory’s emptiness” is precursor to other paths, “direction as … directionless,” an “all day nakedness and coming on the edge of to explore … ” (531).

Homecoming as the ritual of youth returning to the alma mater becomes the metonymic value for something much greater in Irby’s work. A hieros gamos, a marriage of heaven and earth, spirit and matter, the profane and the sacred, emerge when

out there the first home football game fills the town

in here the same shared inner track is celebration

alchemy is each pulvinus, transmutation of the touch to be like light

a paperclip is the mountain top, and the football game, whistling up

there, but to be water and its transformation out

won in the pines’ sound, lost in the pines’ sound, sound in the knobnut

leapt for and gulped

so for the marriage past, far to the Northland gone

this is the night mail, crossing

crossed at

the border (533)

Such a marriage for Irby in “September Set” involves “the sphincter of arousal in the brain.” This is “pilgrimage,” from carnal flesh and mind, unified form. Here, “time is the life of the soul as it passes from one state of act and experience to another and is not outside it” (534). States of experience like “solitude and grieving are also instruments of vision.” (537). These states are shared as supernatural urgencies in “the rock ring jell in the eyes of the crow, in the cry of the jay / brought around” (541). The constant chorus of the work is renewed: “come enter again return” (544). While lovely phenomenal details of landscape are activated in the poems, the concern for Irby is with a sense of magical self-transformation — not particularly a willful change in the character of the self, but an inevitable progression of form that is in constant variance, pressure, environmental stress, and formation. In “[étude homage, Religio Medici]” he writes: “How we outlive our notions of ourselves / and never know the others in there all along / give them away, become them / only at a stretch imagine / and the stretch is good” (556). The stretch, the bodily motion, tempers spiritual concern, the inevitable patterns and mysteries of one’s variances.

By “[Ides],” the final poem of Ridge to Ridge, the “transitional affluence of life itself” gives way to grief “and wanting to watch something out of the swallowing up part of the made world / to juxtapose to and let the forgetting forget itself for a while” (561). The problem of memory and forgetting, as for Augustine, interferes with a more truthful vision of what remains just beyond perceptive apprehension. The poems in this sequence, unlike others prior to it, begin to acknowledge the invisible, internal landscape that precedes and extends beyond one’s limited abilities to retrieve and process an experience and knowledge. Instead, there is a yearning to “watch something out of the swallowing up part of the made world.” Such Gnostic sensitivity admires bodily form, but also entrusts perspective to a creative, generative potential just beyond reach of that bodily apparatus.

Ultimately it is the essential mysteries and purifications that possess Irby’s imagination. His writing pressures an easy sense of perception in contemporary contexts. He performs ways of knowing and seeing, measuring and valuing. His performances in poetry enact basic conditions in art that reveal, shape, renew, and reorient attention of dynamic objects in equally dynamic spatial fields. The advance Irby makes on the New American poetry is through the humble position of the bardic figure who refuses the role of tribal boss. Exemplification and the ongoing task of poetic labor figure much more predominantly. Irby’s work invites readers to measure their own readings by an effusion of art that makes both music and narrative of shared human experiences. Such an art in narrative can expand the capacities of readers by taking the qualitative progression of formal appeal as the defining feature of serial relationships. In this Irby has always been generous, though in Ridge to Ridge the views are reduced, quieted, eased forth with critical self-awareness. Through a qualitative progression that relies on a renewal of images, phrases, talismanic figures, and scenes of homecoming, Irby establishes a narrative sequence that provides intense pleasure as lyric offerings, but that also confronts readers with an essential story of change, strategies of perception and of being, and, especially, with an appreciation for the renewal of life in the constant flux of landscape. I have been privileged to read Irby for many years, and to speak with him, and to see the Kansas of his imagination. Such geographic necessity informs the heartland of awareness.

1. Burke identifies five essential elements of formal appeal, arguing that these contribute to arousal and fulfillment of desire. They are:

1. Syllogistic progression: advancement step by step (example: mystery stories)

2. Qualitative progression: like foreshadowing — advancement of narrative through echoes, returns, approximate relationships based on nonsyllogistic sequences (much poetry, including Irby’s serial forms, progresses in this way)

3. Repetitive form: restatement of the same thing in different ways

4. Conventional form: forms an audience takes for granted (stories with beginnings, middle, ends)

5. Incidental form: metaphor, paradox, disclosure, reversal, etc — any of the small components that sustain a narrative

Additionally, forms can be interrelated or be in conflict. Most of the narratives we encounter are composed of conventional and nonconventional elements; they advance at times through syllogism, at others through amplification of dominant themes; their metaphorical components often produce closure or paradox, challenging our ability to intervene with our own presuppositions of form. I use this sense of qualitative progression as a way to understand serial poetry, and also as a way to address the progression of Irby’s narrative sequences.

2. See Credences 7 (February 1979), ed. Robert J. Bertholf (Kent, OH: Credences Press). Other contributors include: Eric Mottram, George Quasha, Charles Stein, Paul Metcalf, Reginald Gibbons, George Butterick, David Bromige, Paul Kahn, John Moritz, Bob Callahan, Linda Parker, Mark Karlins, Larry Goodell, Roy Gridley, and a bibliographic “checklist” by Robert J. Bertholf.

3. See Robert Duncan, The H.D. Book (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), 96.

4. Following Olson and Dorn, Irby continued adjacently to pursue cultural and topographical patterns in the environment in ways Carl O. Sauer describes in his influential essay “The Morphology of Landscape,” which determined not only the disciplinary concerns of cultural geography but also motivated many of the New American poets. In essential ways, it laid the foundation for a midcentury poetics, particularly in the West, which was based on attention to the ecology and environment in a creative and physical sense. See “The Morphology of Landscape,” Land and Life: A Selection from the Writings of Carl Ortwin Sauer (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1963).

5. See Olson’s “Projective Verse” (1950) Collected Prose (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 15–26.

6. See for instance Jeffrey Walker’s argument about the asymmetrical relationship between the bardic poet and his (largely his) audience in Bardic Ethos and the American Poem: Whitman, Pound, Crane, Williams, Olson (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1989).

Edited byWilliam J. Harris Kyle Waugh