John Taggart: From his own words

As Lorine Niedecker once wrote of Louis Zukofsky, I can write the same of John Taggart: “I [am] fortunate enough to call him friend and mentor.” I met John back in 1985 as a freshman at Shippensburg University. By some strange luck, I like to believe it was the hands of the gods, I was assigned John as my adviser. I was an undeclared major with “poetry” listed under Hobbies on my application. Perhaps this was the deciding factor that got me placed with him; whatever the case, that placement turned into a mentorship and a friendship that have lasted to the present day.

I have no desire to talk about John’s work in a critical way; the work stands on its own. My inclination is toward biography. Once, when speaking with John on the telephone I let him know that I was reading a biography of Gerard Manley Hopkins, and then I made the comment “I don’t know why I like biography so much.” And John remarked “It’s because you’re nosy.” We both laughed. I would defend myself and say “curious.” I think curiosity is any writer’s hunger. So through the thoughts and advice in John’s letters came the revelation that the one I called Dr. Taggart was also human. Just such a reward is probably one of the reasons why correspondence is so desired.

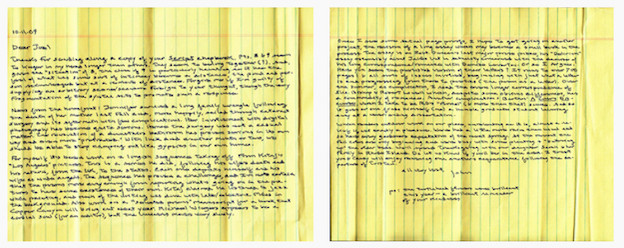

And John’s is a true correspondence, i.e., handwritten. I have included parts from early letters and worked forward through the years. I didn’t start out looking for anything in particular, just for what I thought was most interesting, but now that the selections are next to one another I can see that there’s a definite “religious” theme about them. But what more could be expected; as John has written me on more than one occasion, “My ‘project’ is to rewrite the Bible.”

______________________________________________________________________

Sept. 10, 1989

Still, for a number of reasons you may come to agree with, I’m happy to be the age I am and can imagine little worse than being time-machined back into earlier moments. If nothing else, as the example of Lorine makes clear in her own life, the art can truly get better as you go along; you can get better, you can get to the point where you’re doing what you actually want to do. One of the curious things is that something of a return is often involved. (The Loop title is no accident.) If my own experience is anything to go on, there can be a movement forward. Of course we think we’re moving forward all along, but I have my doubts. In my case, there had to be not only a going back, e.g., to the church, but a consciousness of what was involved: this is me.

Jan 10, 1990

You ask about religion. Having been born into that profession (not to forget, the name Taggart means “priest’s son”), it has taken me a long time to acknowledge it as my world and context. This is not quite the same as having a “view” about it. You can find traces of that in my poems, but the main thing is the acknowledgement itself. It is what is missing in much otherwise admirable contemporary work. And I think that must eventually tell against it. You don’t have to be a believer, don’t have to like it, but you have to have some sense of it to be truly human. To put it most flatly, it has to be part (if not the whole) of your vocabulary. Per Dickinson & Melville, remember that you can belong to the loyal opposition.

12-9-92

Enclosed is a recent poem [“Into The Hill Country”]. It’s a version of the visitation (Mary & Elizabeth). It may be that my “project” is to rewrite the Bible. No lack of work to be done!

September 24, 1995

Growing up in a series of small Midwestern towns, some of which were quite attractive, it’s fair enough to say that the world of books was much more alive and real to me than my immediate surroundings. And this extended to the church. I had, of course, to go every Sunday. But I would always go with at least one book of my own choosing, which, whatever else, would never be the Bible. What biblical knowledge I have is either the product of much later reading or recollections from Sunday School or my Father’s sermons. Enforced attendance makes for resistance and so I was a rebel, if on the subdued side, from the beginning. Dostoevsky or A. J. Cronin (popular novelist of the 50’s) or Salinger would always be in my church suit pocket or craftily (I thought) secreted inside my hymnal. Enforced attendance also makes for the development of a “critical” intelligence. I listened closely to my Father, always on the lookout for flaws in his arguments, weaknesses in his presentations. It makes me keenly aware of the public (spoken) exertion of power. I couldn’t help noticing how he moved a congregation one way or another. And there were other things I couldn’t help but notice: the theatre component of the service — robes, costuming, music, liturgy, the ritual of communion in particular — which, at home & behind the scenes as it were — were always discussed in terms of theatre, judged/evaluated as performance. And here & there I also noted instances of quiet, utterly sincere faith & devotion, persons of that quality. Now the odd thing is that none of this shows up in my early writing, either prose fiction (with which I began) or poetry. I wanted to sound like Robbe-Grillet or Celine or Stevens. It was only when I had done the Pyramid book and felt myself to be at what might be called an impasse of experiment, when I began to question the idea of avant garde experimentation as a worthwhile goal in itself. That it all came back. That is, I felt compelled to acknowledge the existence/value of my own experience and try to do more with it than a version of confessional reporting. In terms of music, it meant turning away from Stockhausen, Cage, Xenakis & others to the wonderfully (terribly?) sexy and innocent rock music I’d grown up with in the 50’s & early 60’s, much of it, importantly, black music. And, true enough, church music, hymn tunes, was involved. This is why Ives often moves me to tears. I can’t help but recognize the hymns he draws from and, as with the piano and violin sonatas, draws away from. A key in this was Kierkegaard, whom I read as a high school student but without anything like real understanding until much later on. He is for me the essence of the Protestant intelligence, which is not to deny his wide learning and considerable wit. The difference is that, finally, I don’t make the movement of faith. So in the end I remain resistant, even though I know I’m dependent upon what’s being resisted. It’s also the case that I have an abiding respect for what’s being resisted, not simply as “material” but as a reality in my life. All the church windows of very ordinary churches, not cathedrals, are real to me. And as they constitute a return to reality, they are more than simply real as actual; they are the windows through & by which I see. Which may simply be another way of saying that, essentially, I’m a rather elderly child, a child of pain as I most often feel in confrontation with the crucifixion picture/window.

A 1973 letter from Taggart to Ronald Johnson (courtesy of Peter O‘Leary).

April 13, 1997

At the moment I’m collecting some notes for the Zukofsky conference Bob Creeley is sponsoring at the end of the month. Luckily, Melville was all too much with me when he called, and the arrangement is that I’ll read a poem (The Pyramid Is A Pure Crystal) instead of reading a paper. The notes are to function as an introduction to the poem, which was dedicated to L. Z. when it was first published by Elizabeth Press. It’s been years since I last looked at this poem: a peculiar experience to revisit one’s thinking of over 20 yrs ago. I don’t know that I like the poem all that much, but I was intrigued with the boxes which are printed around the tiny poems in each series. It occurs to me that this is what I am: the poet of the box, the poet of boxes! If I could present what truly interests me, it would be something on the order of: the Platonic solids & the box kites of Alexander Graham Bell! Have you ever seen the old National Geographic photo of Bell & dozens of men pulling at a rope to get one of his giant kites (the shape of an abstract wing) into the air? That’s my idea of a good time! Actually, seeing kites at Bell’s “studio” in Nova Scotia was a galvanizing experience for me. There’s something quite magical about those geometric shapes and the delicacy of the materials (silk & very thin strips of wood). Well, I found it magical. A room of one’s own is a good idea, but a workroom filled with giant kites in various stages of construction strikes me as infinitely preferable. For a kite is a crystal made visible, a crystal you can see (inside out) & fly in the air.

January 26, 1998

Came across an article on Ned Rorem in the Times last week. Not one of my favorite composers, but something he said struck me. Approximate quotation: artists aren’t wild, crazy people; they’re the truly sane ones who know what they must do all their lives. And if there’s some appreciation, however slight, that’s great. A decent credo, I think. The only problem is, speaking only for myself, we tend to need reminding what it is that must be done. As for appreciation, I must tell you about an unlooked for example. Shortly before Christmas a Lutheran minister from Kansas called. He’d been struck by the Marvin Gaye poem & wondered if he could send me something by way of, yes, appreciation. This turned out to be no less than 8 cassette tapes of all sorts of music! & as an omen of sorts, the last selection on the very last tape was the opening from Coltrane’s “A Love Supreme.” This is a “project” I’ve been thinking about for some time (a poem in response to that music). A tremendous gift, and I’ll take [it] as a charm for what I know will be a major undertaking.

1.23.03

Thank you for your kind comments on the pastorelle poems. Their opening out into the rural, as you say, was a gradual process: gradually becoming aware of things around our place, literally learning their names, the names of plants as well as of the persons making up our local history. About equally gradual and “unconscious,” picked up as one goes along. Then, again, not altogether unconscious, i.e., reading WCW on American culture, specifically the immediate as local, played a part, almost forcing me against my will to realize/acknowledge that this was, in fact, my culture and, as such, what was to be acted upon in terms of writing. It took some time to get comfortable with single page poems. I like the fact that they’re scattered throughout a larger book. That way the water-torture effect is avoided (or so I hope).

8.9.07

Not sure if beginners know what they need in their beginnings (an older recognition that one may have been lucky even if that very luck is resented). There seems to be a basic choice between writing as if each try is a new beginning or using what you already have and trying to extend/push it a bit further. So the examples of WCW & Stevens. Main thing: try to avoid writing the same poem over & over!

Edited by Matthew Cooperman