Suffering into shape

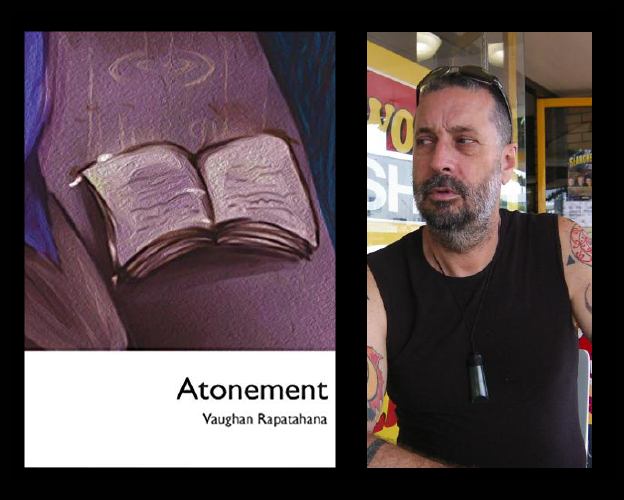

A review of 'Atonement' by Vaughan Rapatahana

Atonement

Atonement

Atonement is the latest collection of poems by the New Zealand Māori poet Vaughan Rapatahana. It follows his 2011 collection, Home, Away, Elsewhere (Proverse, Hong Kong), and like its two predecessors mirrors his peripatetic lifestyle. Rapatahana has worked in Nauru, Brunei Darussalam, the People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong, the UAE, and Australia, and had a varied career before becoming a writer: he worked as a secondary teacher, a special education adviser, a house painter, and a storeman. Although known mainly as a poet, Rapatahana has also written prose fiction and academic articles and has coedited two collections of articles on linguistic imperialism, or the dominance of the English language at the expense of other languages such as te reo Māori, the indigenous language of New Zealand.

Although the title Atonement leads one to expect a more personal and intimate collection, most of the themes are inspired by place, as in the titles “santo tomas deluge 2012,”“macau on a tuesday,” “mauritian time,” and “auckland triptych.” As with most of Rapatahana’s poetry, this collection consists of shape or concrete poems. The typographical arrangement of words is as important to meaning, as are conventional elements of poetry such as word choice, rhythm, rhyme, or imagery. Conventional capital letters and punctuation are largely ignored. The poem “he patai” (“question” in Māori) is laid out in the form of a page-sized question mark. In “nada near naha,” American troops in Okinawa are described as

crew cut & w i d e – e y e

naïfs

in ill fit mufti[1]

In “east coast hamlet,” derelict buildings are

tumble-d

o

w

n

stranded

o n t h e s a n d (36)

The poems cover a range of intense emotions, from dark and mordant images of injustice to regrets about personal loss, aching love and betrayal, feelings rendering by powerful, and surprising imagery as that in the poems “god is a chain letter” and “sarcophagus of love.” The vagaries of the weather do not escape the poet’s acerbic similes and metaphors:

the rain

struts past

my window

like a petulant dog

shakes itself ragged

while pissing on

the spindly plants (92)

the morning is

a washing machine (98)

In some poems there are traces of the extraordinary imagery used in his novel Toa, where inanimate things are often personified:

the dawn picks itself up

from crumple of night

and shakes its skinny shoulders

like a blind dog (14–15)

the driftwood

eyed us

suspiciously (55)

or described as creatures who were once alive and are now dead: “the butchered carcass of a town” (62). The personal poems are quieter and more reflective, expressing regrets and uncertainties, as in the poem “in a cafe, on a boulevard”:

we ate there once

perhaps … maybe

it was coffees …

in the gloom of minds’

mauvaise foi

silhouettes loom (81)

Or in “a forced reunion”:

even now, when it’s far too

late,

there’s the ‘what if ’ and the ‘why didn’t I’

and a hundred other such

barb-armed offenders (34)

The poems in Atonement embrace down-to-earth themes, written in a direct, conversational style and are in most cases readily accessible. Some of them require a bit of an effort on behalf of the reader, although the effort is well worthwhile. For example, the poem “tinian” begins

there’s nothing much

on tinian

[except the casino $$$$$$$$$$] (70–71)

and then reveals, several lines later, that this run-down nondescript island in the Marianas is the place from where American bombers took off to firebomb Tokyo and to nuke Hiroshima and Nagasaki, killing

thousands thousands thousands thousands thousands thousands

more …

The poems in Atonement are peppered with non-English words, most of them Māori. The meanings of the Māori words are given, and the poem “he maimai,” a lament for the dead, is followed by an English version. A perusal of Vaughan Rapatahana’s writing shows that he is a strong militant against linguistic imperialism: that is, the attrition and destruction of indigenous languages in former colonies by the languages of the colonial powers, foremost among them being English and French. This accounts for the constant references to Māori and the poem “sloop of discourse,”which rails against the “whiteman mariners” (the British) exporting their “barmy lexis” (English) in “gallivanting galleons,” “netting the neophytes” (104) who are led to believe they will need English in order to study and progress. The poem concludes with the line "i e l t s rules the waves.” Indeed it does. IELTS (the International English Language Testing System) is an English proficiency test taken by three million people every year, including students and prospective migrants hoping for access to the Anglophone world. The situation applies to nearly all of the countries mentioned in the poems. Why is Rapatahana’s collection called Atonement? There is little evident mention of atonement in the texts. There is, however, an evident and crying need for atonement: atonement for past mistakes, the “why didn’t I?” of past relationships; for the violence in war; for injustice and poverty; and for the pass-or-die tyranny of school children in all too many countries. Whatever the role of the book’s title, the collection of poems is a powerful and multifaceted reflection on human suffering. Another remarkable feature of this book is its size. Its 124 pages of text are miniaturized in what looks like a trigesimo-secundo format (10 x 14 centimeters), a little larger than a smartphone. It’s a portable tome, designed to be read on a bus, a tram, a ferry, or a plane. So, how to sum up Atonement in this context? A publicity agency may describe it thus: “A pint-sized but powerful package of poems, conveniently designed for your pocket or purse! Don’t burn after reading!”

1. Vaughan Rapatahana, Atonement (Hong Kong and Macao: MCCM Creations and ASM/Flying Island Books, 2015), 72.