Serious play

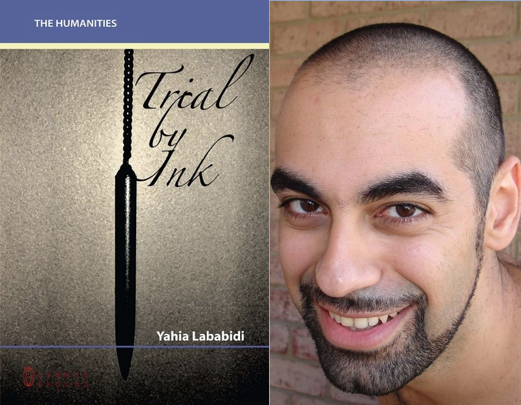

A review of Yahia Lababidi's 'Trial by Ink'

Trial by Ink

Trial by Ink

As the subtitle — “from Nietzsche to Belly Dancing” — suggests, Yahia Lababidi’s essays wiggle their hips in many directions, from sacred to arcane, from pop to professorial. What he admires in Wilde is just this, the writer’s “ability to play with serious subjects. To make light of them” (12). In fact, the true subject of Lababidi’s writing would seem to be these poignant interchanges between seemingly disparate spheres. The spiritual and sociopolitical resonance of belly dancing. The small, contained dynamic between reader and text, between the personal and universal.

Born in 1973, Yahia Lababidi is an Egyptian-Lebanese poet, essayist and aphorist. His work has appeared in journals throughout the world, including Agni, Cimarron Review, Idler, Poetry, New Internationalist and Bidoun. The Independent (UK) chose Signposts to Elsewhere, a collection of aphorisms, as one of its Books of the Year (2008). His writing, much anthologized, has been translated into Arabic, Slovak, Swedish, Turkish and Italian.

Trial by Ink is rather difficult to categorize. In one sense, the collection avoids Emerson’s foolish consistency by taking on such a broad array of subjects and approaching them in a variety of moods and modes. Lababidi offers up literary essays, cultural critiques, and startlingly astute examinations of pop stars. His voice and method are distinct and consistent, however. The essays always encompass, in addition to the surface topic, a study of the author’s approach to that topic. In the preface, Lababidi calls his book “a sort of mental autobiography and a collection of judgments” (ix). He maintains that he writes “to determine what I think about a given subject” (ix). Trial by Ink is admittedly, though unabashedly, subjective. Nonetheless, it doesn’t come off as a string of unsubstantiated and freefloating opinions — the love child of Intro to Philosophy and the blog age — but rather a coherent series of shrewd, thoughtful reflections.

Lababidi’s writing is rapacious with quotation, allusion and learned reference. Rimbaud, Kierkegaard, Eliot, Wittgenstein, Heidegger, Ruskin, Heine, Sontag, Gide, Socrates, Melville, Montaigne, Arnold, Pascal, Rilke, Gogol, Nabokov, Henry James, Beckett, Larkin, Stephen King, Chuck D and (almost literally) countless others cross the stage of this slim book. Nietzsche walks the boards so many times you’d think he was looking for his hat. This never seems forced or pretentious, however, but rather enthusiastic and necessary. Many of Lababidi’s essays concern readers, texts and the cagematch between the two, and he often inserts himself, as both reader and writer, into the fray. He portrays the writer as martyr, invalid, abstainer, submissive, mystic, and healer.

Trial by Ink is divided into three topical sections: literature, popular culture, and the Middle East. The first category incorporates all manner of coherent digressions; biographical, historical, analytical and personal approaches to literature are intermingled. Part II, covering popular culture, embraces Michael Jackson and murder, silence and celebrity, while the last section takes on belly dancing, sexual repression in Egypt, and the many paradoxes and ironies of the modern Middle East. The putative topics, throughout the collection, are diverse, but Lababidi manages to make them cohere through his idiosyncratic perspective and style.

Lababidi is equally deft with the highbrow world of Friedrich Nietzsche and the plucked brow milieu of Michael Jackson. His writerly gaze and attention to significant detail never waver, regardless of the subject at hand. This is Michael on Oprah, fielding questions he never quite answers:

And there he was: an unthreatening, bizarre specimen, a slip of a man, more a geisha girl really, simpering, whimpering and tittering […] And, you couldn’t really take your eyes off his face, not only because it looked like nothing you’d seen — sexual, ambiguous, uncanny, alluring — but because you were desperately trying to read it, scanning its otherworldly surface, rummaging beneath its mysterious skin (70)

This description is lucid and animating, never descending into parody or obviousness, and the prose helps breathe life into the portrait. Moreover, the popular culture essays are funny, which helps leaven the high seriousness of the literary pieces.

“Monks of Los Angeles” is a canny reading of Morrissey and Leonard Cohen, two faces of enigma and melancholy in popular music. Lababidi distills the charms of these singer-songwriters with the quick (yet potent) thrusts and parries that mark his writing. His analysis of their hummable anguish is representative: “By making their anxieties public, these artists assuage the loneliness of their listeners the world-over, while serving as leading lights to brethren of solitaries” (81). Despite a penchant for alliteration, Lababidi strikes another killshot with “brethren of solitaries.”

The Middle Eastern essays are, for the most part, concerned with social, cultural and political criticism, but the writing is characteristically agile, vivid and often witty. In “Empire of the Senses,” for example, Lababidi discusses Egypt’s sexual and gender mores: “a woman’s virginity is governed by a kind of gift shop morality — break it, you buy it” (112). Like the best aphorists, Lababidi can be funny without sacrificing poignancy.

By far the most intriguing element of Trail by Ink is Chapter 2, “The Prayer of Attention: A Conversation with Yahia Lababidi.” The name Alex Stein appears under the title, as if he’s interviewing the author, yet the text is positioned in the third person. Although a conversation did take place, with Stein goading Lababidi with questions and interjections, the piece is presented in standard essay format. The interviewer thus becomes disembodied, or rather more disembodied, than usual, the author refers to this dynamic as “assisted monologue,” though “dialogic provocation” might also work. I hesitate to simplify the piece with any facile categorization. It could be regarded as short fiction or memoir, recalling both the mock-interrogation of Camus’s The Fall and Kafka’s short parables. Lababidi is, with purpose and finesse, manipulating our expectations with regard to genre, technique and perspective; his method is experimental, inciting the piece toward unexpected conclusions, but the reading is never “difficult” or ostentatious. On the contrary, his writing manages to be highly complex and sophisticated without losing its readability or elegance.

Fortunately, “The Prayer of Attention” is as compelling in substance as in style and structure. It’s a meditation upon — a scrum and ruck against — art, inspiration, influence and the individual’s transformation through and because of these things. Lababidi foregrounds his own thoughts and inner-djinns in this essay, even more prominently than elsewhere. This seems to be his special talent, anchoring his own peculiar experience to the universal spirit, Emerson’s Over-soul. The piece is odd, alluring, wholly original, a tour de force and, in my view, the linchpin of the collection.

Although Trial by Ink is chock-a-block with literary allusions, it’s the subtitular Nietzsche who looms most steadfastly over the text. Lababidi, in Chapter 1, mentions the presumptive arrogance of the philosopher, and we might wonder if it’s presumptuous for Lababidi, a virtual unknown, to write about his own work in Chapter 2, sandwiched between essays on Nietzsche and Wilde. Lababidi might argue that all writing is an examination of writing, the self, one’s influences and the irresolvable struggle among the three. Throughout the book, he returns to the idea that you can’t choose writing, but rather writing chooses you, so, according to this model, we can’t hold Lababidi accountable for making himself the center of his work.

Trial by Ink is compelling, ardent and sometimes febrile. The prose is confident and polished; like a frozen lake, it is sturdy yet translucent. Lababidi has a polymorphous, gluttonous intellect, one which is able to absorb and synthesize a wide range of ideas and communicate them in a poised, nuanced manner. In the bravura Chapter 2, he addresses his youth: “Those were the days when I would read and think without sleeping, sometimes for two or three days in a row” (12). Indeed, throughout the book, I envisioned a sleep and daylight-deprived young man stalking and devouring books with vampiric fervor. Literature and philosophy are revealed as simultaneously transformative and self-revelatory. Books can make you more like yourself even as they convert you into someone else. He refers to Nietzsche, for instance, as “him-that-was-also-me” (13). Lababidi recounts going into the desert to read Zarathustra “with the intention and in the belief that I [was] going to encounter that part of myself that [was] not entirely accessible in other circumstances” (13).

Lababidi has very sharp insights about thinkers and artists. He says of Nietzsche’s writing: “It doesn’t care much for you. It may, perhaps, want you there, but it doesn’t need you there. It doesn’t seek to appease the reader. It is not eager to please. It wants only to declare its harsh, bold truths, and if you can stand it, you can stay” (13). Here, the author demonstrates a meticulous subtlety and understanding of one of our most misconstrued thinkers, so often imprisoned within oversimplification and critical misprision (Nietzsche as The God Is Dead Guy or The Fascist Guy). Lababidi is a natural aphorist, but not a composer of shiny-but-fatuous sound-bites. Rather, like Nietzsche himself, he is genuinely gifted with the ability to reduce a truth to its most unadorned dimensions and, at the same time, encase it in a tidy, attractive box.