Sing Our Rivers Red

Tanaya Winder

Tanaya Winder is from the Duckwater Shoshone, Pyramid Lake Paiute, and Southern Ute nations. She is a poet, performer, and activist and is a co-founder of Sing Our Rivers Red (SORR), a collective of indigenous artists, poets, and activists working to help raise awareness around the crisis faced by indigenous women in Canada and the US. According to the Department of Justice, “Native American women are 2.5 times more likely to experience assault in their lifetimes than women of other races. One in three will be raped in their lifetime, and on some reservations women are murdered at a rate ten times higher than the national average.” SORR’s projects include promoting National Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women Awareness Day, now ratified by five states and a handful of cities, and the creation of the “Earring Exhibit,” a traveling exhibit of earrings donated by the families of Native American women who have been murdered or are missing, or in some cases donated by women who have themselves been victims of assualt. The Earring Exhibit has been presented in galleries in Colorado, Connecticut, New York, North Dakota, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Montana, New Mexico, Oregon, South Dakota, and Washington.

I spoke with Tanaya about her work with SORR (and other activist projects) and about her own stunning performance work, which I was lucky enough to witness at CU Boulder last month.

Julie Carr: Can you tell me about your beginnings as a poet? Specifically, was there a moment when your work took a political turn?

Tanaya Winder: I studied poetry as an undergraduate at Stanford University. While there I took classes from Robert Pinsky and others who were teaching formalist or craft-oriented writing. It wasn't until Gabrielle Calvocoressi, who was then a Stegner Fellow, showed me Elizabeth Bishop’s “One Art” that I realized that poetry lives in loss. I was grieving my grandfather at the time and began to write about this. But I did not have the language or knowledge at that young age to know that grief was also historical trauma. I didn’t write much about identity then. It was Cherrie Moraga who inspired me to delve into my ancestral strength and the power of the voice I carried inside me. Later I went to the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque and studied with Joy Harjo, who became my mentor.

Carr: I was particularly moved by your singing in the piece you performed. Can you talk about that?

Winder: I’ve always sung, my family and especially my grandfather encouraged me to sing. But growing up and even into college I kept it private. The dangers of being seen as a woman, a woman of color, and even more a native woman meant that it took me a while to feel ok with sharing my voice this way. But at readings I was presenting very intense and difficult material. At some point I realized that I could sing to help people feel connected and grounded at a reading/performance, that the singing could become a mediator.The power of the song created an inlet in a space where the more painful or intense material could be discussed.

Carr: Can you talk about the origins of SORR and the Earrings Exhibit?

Winder: My sister was in a doctoral program in Canada. From her I learned about the murder rate of indigenous women there. This moved me to study what was happening here. One important detail is that in areas where there are pipelines, the violence against women is even worse. The idea of finding a way to represent this felt crucial to me. So I worked with a group of friends and women to find ways to raise awareness.

Carr: How do you collect the earrings? Do they belong to women who have been murdered?

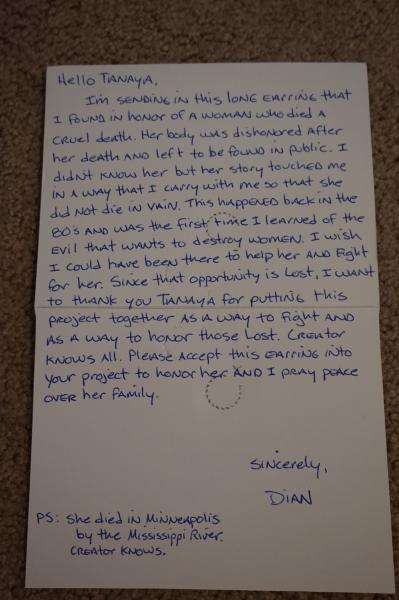

Winder: Yes. In some cases the family members send them to us. In other cases, women who have experienced violence send them. Often people send along notes with the earrings, share their stories with us. We can all bear witness in this way.

Carr: What are you hoping to accomplish with SORR and with your own performances?

Winder: The hope is to ignite healing and hope in other people. People aren’t always provided a space to feel and process. I think of the stage as creating a space for people to remember things they need to acknowledge, feel, or heal. Everybody has the potential to be a mirror for others. What is it we want to reflect back? Working with kids [as the director of CU Boulder's Upward Bound Program] helps ground me. I want to encourage the kids to see all the amazing things about themselves that they can’t see. But adults also need to be shown what we can’t see.

From an Indigenous perspective I'm always thinking about connections to our past, present, and future. I imagine that when people come together, our ancestors are working to help us meet one another and do the work we need to do. The way I think about time allows me to feel that my work is helping to heal some of the historical trauma — the people who were raped and brutalized in colonial times — that they are getting some healing too.

Everybody carries some form of trauma. The question is, are you going to be the person or the generation who stops that trauma and that hurt?

Carr: What are some of the ethical or practical complexities that you face?

Winder: You have to know your place. You have to honor those who come before you. I’m not the first person to do this advocacy work and I won’t be the last. It’s important to talk to those who have done this work before and to talk to those who are doing this work on a daily basis. It's important to learn from them how to do things in a respectful way. It’s also important to be ok with asking for help. At some point I realized that I could not care for the Earring Exhibit alone, that I needed other people to help carry it. I now have three other women committed to caring for it for one year each.

And as a perfomer I have to always ask myself whether I am who I say I am on stage.

Carr: Can you say more about that?

Winder: In 2015, I started Dream Warriors, an Indigenous Artists Management Company, managing hip-hop artists Frank Waln, Tall Paul, and Mic Jordan. We tour separately and sometimes together, performing in the US and abroad. We perform in front of many different types of people from youth to elders; we are always conscious of how we present ourselves and align our lives that way. Basically, it’s making sure you’re “walking your talk.” Further, in order to put our words into action, we started a scholarship to encourage Native American/Alaska Native/Native Hawaiian high school students to pursue their own creative work.

But whenever you’re forging a new path, starting a new project, it’s important to always think about the intention behind what you’re doing. With my book, for example, Words Like Love (West End Press), I was trying to be a bridge between the two worlds I knew well: the university and the poetry that lives there and my community. I wanted to be that bridge without unintentionally disrespecting one group or the other.

I wanted to write a book for the Indigenous teens I work with, something that would help them, but I also wanted to write something that would resonate with the “literary” community, college students and other community members. It's not easy to make those bridges while honoring everyone's perspective.

In closing, I think in the end the best any of us can do is to honor our gifts, our paths, and the passions that have been placed in our hearts. I try my best to be a living example of what I call heartwork. The work that's been placed in your heart is worth honoring. I try to embody love because love is the most powerful force I know.

The Real Life of Poetry