First reading of M. NourbeSe Philip's 'Zong!' #6 (2)

Arlene Keizer

Arlene Keizer’s first reading of Philip’s Zong! #6 is the second in a series of five such readings we are currently publishing. Recently we published Evie Shockley’s, and soon we will publish pieces by Kathy Lou Schultz, Meta DuEwa Jones, and Gary Barwin. — Brian Reed, Craig Dworkin, and Al Filreis

The Bone Alphabet

I came to M. NourbeSe Philip’s Zong! (2008) with too much knowledge to offer the text the complete and utter astonishment it deserves. When I received the invitation to write about Zong! #6, I was already thinking about the way Philip’s book disassembles language and forces readers to consider how “un-telling” the already partial and fragmented tale of an obscene, unspeakable sea voyage might shake the structures that made such a voyage possible (structures that have been altered but are still in place). Thus I’m not sure what follows can be termed a “first reading” of this poem; my encounter with Zong! seems to have always been in medias res.

What I knew: Philip challenged herself to assemble her poems out of the words of Gregson v. Gilbert, the only document that remains from the Zong case. Her choice to confine her source of letters and words to a subset of the Roman alphabet was altered only by her need to propose names for the Africans who died en route to Jamaica: those who died of thirst, those who threw themselves overboard in “frenzy,” and those who were thrown overboard to protect the interests of the ship’s owners. These names travel across the bottom of the poems in the “Os” (Bone) section of Zong! and return at the end of the “Ferrum” (Iron) section. We might call them a running foot (wish fulfillment), underscoring the competing principles of overlap and incommensurability that drive Philip’s project forward. These fugitive footnotes are the strongest reminder of the African people and linguistic worlds lost to the Atlantic Ocean. Having been offered them at the beginning, we miss them in the sections where they don’t appear.

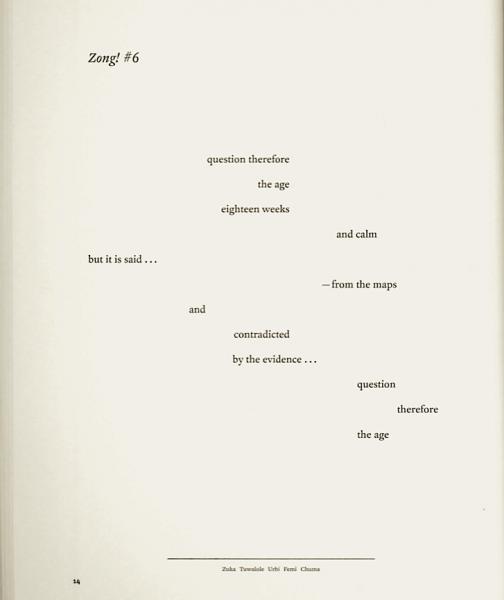

Zong! #6 opens and closes with the injunction to “question therefore / the age,” a call that at first seems simple, given the context of the eighteenth century and its assent to the categories of the classical world: its acceptance that a human being could be placed into the category of res (thing), that an African could be a human res. But when did this age end?

The number six makes me wonder about the length of the sequence. Upon counting, I ask “Why are there twenty-six ‘bones,’ as Philip calls the first set of poems?” Considering the number twenty-six in light of Philip’s obsession with language gives me a flash of insight: these first poems are what I now call Zong!’s “bone alphabet.” They provide the conditions of possibility for the pieces that follow. (Philip calls the four subsequent sections “a translation of the opacity of those early poems.”) And as I slide along the tragic Moebius strip of this book, I cannot forget that this bone alphabet is drawn from Gregson v. Gilbert and numerically matched to the Roman alphabet.

This draws my eye down to the bottom of the page, to the running feet of “Zuka Tuwalole Urbi Femi Chuma.” My next question is “Why these names and not others?” From her “Notanda,” I know that Philip researched Yoruba names. Knowing little about African languages, I begin to wonder if, though written in Roman letters, these names might clearly mark linguistic difference in some ways not immediately apparent.

At this point, I have to confess to my obsessive nature, a hallmark of my character and one of the deepest adjuncts to my creativity and critical drive. Some texts — the ones I love best — fill me with the need to KNOW. I want to tear them open, climb inside, and stitch the pieces back together over me, understanding them through wild immersion and imaginative reconstruction. Zong! seems to invite this. I copy down all 250 names, longhand. I check to see which letters appear in them, and realize that “q” and “v” are missing. What might their absence signify?

I begin to do some research on Bantu languages, the group of languages spread across the widest swath of the African continent. What I learn quickly is that the Roman letters “q,” “v,” and “x” do not correspond to Bantu-language sounds. Of course, there are also Bantu sounds that cannot be rendered with individual Roman letters. When I come upon this information, I become lost, for a moment, in admiration of Philip’s devoted invention, her ameliorative yet anti-lyric practice. I am inside the poem; it settles over me like a polyglot net. These names fracture time, mixing the living and the recent dead into the story of those lost in 1781. (I know some of these names.) These names break the bone alphabet, the Roman alphabet. Reading Zong! #6 with this understanding makes me notice that “question” and “evidence,” two of the most important words in the poem, use letters missing from Bantu sounds. What do I make of this? (And “x” has made it into Zong!’s subscript pantheon — clearly we cannot write any history of the African Diaspora without this letter and its Cartesian violence.)

Zong! #6 takes its words from the argument in favor of the murderous captain and his complicit crew. The lawyers for the captain and the ship’s owners try to set aside the question of the morality of slavery: “It has been decided, whether wisely or unwisely is not now the question, that a portion of our fellow-creatures may become the subject of property. This, therefore, was a throwing overboard of goods, and of part to save the residue. The voyage was eighteen weeks instead of six …” You cannot write “overboard,” “save,” or “voyage” without the Roman “v”: “question / therefore / the age.”

I close the book. My “first reading” of Zong! #6 has been a vertiginous journey.

I drink in the uncanny beauty of Zong!’s cover: the lower part of a femur and the upper ends of a tibia and fibula are set against a silver-grey ocean. A scarlet circle highlights the fanciful knee joint, which looks like a winged vertebra. Eventually, that red punctum pushes a memory to the surface. Taking the place of the knee is another form of articulation altogether — an adinkra symbol from the Akan of Ghana: Gye Nyame, translated into English as “I fear none except God.”

Arlene Keizer is associate professor of English, comparative literature, and African American Studies in the School of Humanities at the University of California at Irvine. Her current book project analyzes the work of the African American visual artist Kara Walker as a window into black postmodernism. Other projects include essays on the ways in which African Diaspora intellectuals have engaged with psychoanalytic theory and practice and essays on memory and theory.