A conversation with Alice Notley on the poet's novel

Laynie Browne: In your recent book, Songs and Stories of the Ghouls, you write:

“Poetry tells me I’m dead; prose pretends I’m not” [1].

Can you elaborate on this statement? To put it in context, this line is embedded in a section where there is a momentary switch from prose to poetry: “I’m afraid prose won’t go deep enough.” A few lines later “And yet I go on in prose.” You suggest limitations of prose but a choice to continue in prose. Or maybe what is necessary is the movement between the two forms within the work?

Alice Notley: “The Book of Dead” contrasts two states, that of Dead and that of Day. Day is what we have generally agreed life is; Dead is a world where boundaries are erased. It resembles dreams and is where the ghouls live.Poetry is more like Dead than like Day, but prose is more useful for describing what goes on in Dead — how it works. Prose is more useful for flat and general statement. Poetry tends to abolish time and present experience as dense and compressed. Prose is society’s enabler, it collaborates with it in its linearity. A poem sends you back into itself repeatedly, a story leads you on.

Browne: I am especially fascinated with your statement “A poem sends you back into itself repeatedly, a story leads you on.” This seems a great insight into beginning to understand the tremendous fluidity you have in moving from poetry to prose and between each of your poetic projects. Can you elaborate ?

Notley: A poem is never over when you finish reading it, and you can’t possess it linearly or cumulatively even. You have to keep rereading it to try to understand it — it isn’t flat, and if it’s relatively transparent then that’s a mystery too. A poem fascinates, and traditionally you end up unconsciously memorizing it like a song. Whereas with a prose story you keep wanting to find out what happens and so you never stop. A story is pretty flat, but suspense keeps you going.

Browne: Do you think of narrative differently when moving to prose?

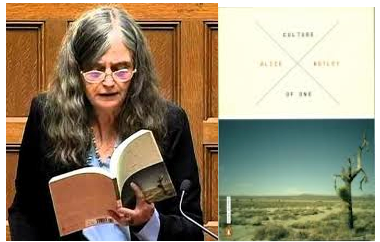

Notley: Yes. I usually prefer poetry for narrative, but I sometimes have to slow down to prose in order to get at what I want to say. And sometimes I want the sound of prose. It is a more lento sound; I have a tendency to write books in sonata form, fast - slow - fast, and Ghouls is like that, as is Désamère. Here, before I forget, I want to say that my most novel-like book is Culture of One, which is a book of poems, but has character, plot, dialogue, and all the trappings of a novel. But back to Ghouls, I found myself wanting to describe this world of Dead, and I would have done it too fast in verse and it would have been harder to get. I was essentially telling it to myself in prose as I began, and I decided to follow the prose impulse.

Prose slows and demands more words. I like poetry for narrative because it’s so much faster and I can leave out so much more. I get sick of those little words -- all the articles and the she-he stuff, I detest scene-setting. I always skim-read novels when I can. Prose fiction limits experience too much, it believes in climaxes and endings as if life had them -- poetry uses them for shapeliness and not much more. When I move to prose I think about what I’ll get out of it. I usually feel something different happening in the sound and the thought process, and then I think about whether I want that. I have some very short stories in the middle of In the Pines influenced by having read Kawabata’s Palm-of- the-Hand-Stories. I guess what I got out of them was a feel for collaborating with society, as if I needed that at the time; but it was fun to get to be so short. In “The Book of Dead“ I got to take pleasure in Medea’s and the narrator’s characters, which I probably wouldn’t have done as much if I’d written the book in poetry. I don’t really believe in character, and in verse I let it take care of itself more, whatever it is. But Medea is a fiction, she just is that because of her historical longevity and implications and thus has to have a character. I made her funny and also generous.

Browne: When I asked you about the Poet’s Novel, your immediate response was to talk about the middle sections of Desamere or Songs and Stories of the Ghouls, which might be considered novellas. What I’m wondering is why of all of your texts would you say that these might be novellas, as opposed to say, any other of your texts?

Notley: Because they are in prose and observe the rules of prose fiction. They are fictional prose works of a length between the story and the novel. I began my writing career as a fiction writer. I was accepted by The Writers Workshop as a fiction writer on the basis of a short story and went there (Iowa) to learn to be a novelist. My MFA is in fiction and poetry. I have a feel for the traditional form of the story/ novella/ novel — I think it’s a difficult form to execute though its language is usually too slow and flattened out for the way my mind works.

Browne: You mentioned that Culture of One is your book which is most like a novel.

You write in a section titled “The Book of Lies”:

“Do you believe this stuff or is it a story?

I believe every fucking word, but it is a story.” [2]

In that quote, the characters are thinking, (Marie and Eve Love), but the question and answer seem central to this question which runs through much of your work asking what is real and what is imagined- or often, what is real and what is fabricated for the benefit of few. So my question is, do you think that poetry and fiction play different roles in awakening a reader to the “real”? Can both be equally potent? Do you believe that the best poetry illuminates the difference between honesty and falseness in some way? Do you see that as part of the task of the poet?

Notley: You are leaving out an essential fact here: Culture of One is a work of poetic fiction. It is poetry and fiction. The two are not different from each other, not dichotomized or at cross-purposes. I am often a writer of poetic or verse fiction at this point, and I prefer poetry for fictional ends. If you mean do poetry and prose fiction play different roles in awakening the reader to the “real”: prose fiction seems to me to be incapable of doing this, although it may provide some amusement and distraction. I’m not sure poetry does this either — and I’m certainly not interested in being honest. It’s more as if poetry, great poetry, is the real — the real is composed of endless, overlapping poems. Stories, on the other hand, are imposed on the real, in an afterwards sort of way. But I persist, too, in going after them but in poetry. I must think that if something is happening, it’s happening in the way of poetry, in layers, densely and all at once as far as temporality is concerned.

Browne: You mention that you began your career as a fiction writer. Can you talk about when and how you began to gravitate more toward poetry? When did you begin to think of yourself primarily as a poet ? And what pulled you in that direction ? What drew you initially to prose? Or was it always both that were of interest?

Notley: I started writing poems as soon as I started meeting poets and hearing poets read their work, immediately after I arrived in Iowa. I had begun with stories, because that seemed the normal thing to do. It never occurred to me to write poems as long as I was in a culture of prose fiction — that which it all still is. There were two things going on with me as a undergraduate: I was trying to learn how to write stories, and I was trying to understand how classical music worked. I wrote my stories a little as if they were movies: I tried to visualize everything that happened action by action, moment by moment. And I took music courses trying to figure out something about musical composition. I remember analyzing the tone rows in Webern’s Symphony Opus 21 (I think that’s right) for a music course and then receiving an A- because the analysis was correct but there seemed to be no reason to do this — the minus. When I got to Iowa and began to write poems, I think I had finally discovered how to compose on some level; I was composing the poems. They proceeded harmonically and were both emotional and abstract. I of course would never have said this at the time. The second poetry reading I attended was by Bob Creeley, and I was tremendously impressed by his musicality and the fact that I couldn’t understand him and didn’t at all mind that.

Browne: On the surface there is the way any text appears on the page (verse or prose). But prose doesn’t always indicate fiction, non-fiction, poetry, etc., and I’m more interested in other determinants such as your intent. Does a movement to a “poet’s novel” involve any shifts in process, consideration of language, content or structure? What circumstances or projects might impel your work to shift genres?

Notley: Now we get to the question of whether there is such a thing as a “poet’s novel” and I would probably say no. The phrase makes a poet’s novel sound like a failed novel. Or we could be talking about something like the experimental novel, but how is that different from Joyce? I don’t always know why poets call their works novels. But I assumed from your initial email that you were talking about prose fiction written by poets in some sort of traditional way not experimental way. It’s possible I don’t know what we’re talking about!

Browne: I wonder if there were times you felt more drawn to prose- both as writer and reader? What circumstances draw you toward prose? What works of fiction do you return to?

Notley: I’m never drawn more to fiction than poetry, except when I need to read a lot of detective or spy or sci-fi novels. I sort of disapprove of fiction. It’s always telling people what they’re like and what life is like. It constrains us. When I want a prose hit, like I need the pace of it, I read guides to rocks and wildlife. I read the others for story; I don’t watch TV or go to movies. I suppose I read genre novels because they’re like crossword puzzles, though some are very good. Ross Macdonald sometimes seems to me as good as any contemporary poet, especially if you take the whole oeuvre all together mixed up -- it’s like a long poem. I’m very fond of the Dune books, but now I remember what happens in all of them and can’t read them for awhile. I’ve recently over-read Len Deighton’s Bernard Sampson books, the Spenser books of Robert B. Parker, and, I’m afraid, the Stephanie Plum series by Janet Evanovich. I don’t have very good taste. However, if you wanted to go at it from another angle, it’s possible that my entire poetic output, practically, owes its existence to Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying. Also the one where Reba walks barefoot and pregnant to wherever it is. I haven’t read these since I was young, but they are the ones I read when I didn’t have to read books for a college course, when I was home from college in the summer. I was fascinated by how I couldn’t understand them and read them repeatedly before I became a poet. About ten years ago for teaching purposes I opened up a novel by Faulkner and my whole arsenal of tricks was there; I closed the book quickly and freaked out.

Browne: It would be great to hear a bit more about how Faulkner is such an important influence.

Notley: I can’t talk about Faulkner, I can’t say his name again.

Browne: Are there novels written by poets that have been particularly important to your writing?

Notley: Phil Whalen’s Imaginary Speeches for a Brazen Head has been very important to me. I read it too many times awhile ago and haven’t been able to reread it since, but I’m currently conscious of its influence on me in regard to its notion of time. Doug’s The Harmless Building has also been important. And I typed up Ted’s Clear the Range for publication — it is a novel made by crossing out words in the eponymous cowboy novel by Max Brand. Since I did all that typing I rather imagine that I’ve been influenced by it.

Notes:

1. Alice Notley, Songs and Stories of the Ghouls (Middletown CT, Wesleyan University Press, 2011), 39.

2. Alice Notley, Culture of One (New York, Penguin, 2011), 74.

The poet's novel