The poet's novel: An oxymoron

The poet's novel — what is it?

One of the first pleasures of exploring the poet’s novel is conversation with other writers on the subject. I’ve been collecting thoughts. With gratefulness to all who responded, I patch together in this commentary many borrowed insights. One thing I’ve noted is when asking if the poet’s novel exists, I am often answered with another question as to what I mean by the “poet’s novel.” Kevin Varonne wrote “do you mean a novel that poets like or feels poetic, or do you mean a novel-in-verse kind of thing?” My answer is yes, I am interested in exploring a full spectrum of what one could mean by the term.

Andrea Baker writes, “Cadence is on display. The narrative has an open endless.” I am fascinated with the brevity and compression of this response. Cadence is less rarely on display in prose. “Display” suggests a visual element, and cadence a musical concentration. So the poet’s novel is in a way this contradiction in terms. How does the visual aspect work? Juliana Baggott writes, “You find yourself reading paragraphs and thinking of line breaks — that’s the first clue you’re reading one.” The careful reading Baggott suggests is akin to the breathwork involved in reading poetry aloud. “The first clue” leads us back to a quality of attention. One could read anything mindlessly and miss the work entirely. In fact, I know from personal experience that it is possible to read a book mechanically while thinking completely unrelated thoughts. This is a skill I developed when compelled to read the same texts over and over again to young children. An attention quite opposite to that is required when reading a poet’s novel. The pause, breath, or “line break” between paragraphs is similar to slowing the speed at which one consumes anything desirable so as to linger. When reading a poet’s novel I find myself slowing not only in order to stretch out the reading process but to reconsider or absorb a phrase or sentence. This deliberate stumbling and stopping is an “open endless.” It takes you back, in the opposite direction of “finishing.” Poet’s novels are often texts which move in multidirectional modes simultaneously.

“Open endless” as a way to discuss narrative is also curious. Did she mean to say “endlessness”? An abruptness to “endless” and “open” leaves one stranded. I may be free associating here in ways Andrea did not intend, but it seems relevant to say that one can count upon a conventional novel not to be “open endless,” not to leave anyone stranded. A poet’s novel is less accommodating. The writer of a poet’s novel is less concerned about whether or not a reader feels invited. Narrative becomes a looming question or an undomesticated animal, in the sense that there is no expectation for neatness, action, linear movement or conclusion. Plot is not a motto affixed as a beacon or held aloft as ideal. One does not know what a squirrel, climbing in through your window and under the bed, will do. Instead, a reader listens.

“There is usually an attention to words that is beyond or slightly different from the attention to language one would expect with a literary novelist,” writes Laura Moriarty. The quality of attention to language is another aspect of the poet’s novel which is essential. A text may be written at the level of the sentence, the phrase, the word, or phoneme. In any of these units of composition, attention to language is heightened and foregrounded to the extent that language itself, the medium in which the form is pronounced, becomes visible as material. This is not true in most conventional novels, in which language can be translucent to the extent that a reader can forget it entirely.

Tyronne Williams writes, “To use Jakobson’s old distinctions, I think of poet’s novels as driven less by metonym and more by metaphor though the fact of the matter is that definition reflects merely my own prejudices.” A work that proceeds by metaphor must insist upon an “open endless” when it comes to narrative. One way to think of this suggestion is that the poet’s novel has an entirely different engine. Associative process often creates a work which is not discovered by the author until it is written. In other words, “writing is thinking” (Bhanu Kapil). And here we circle back to intent. Regardless of how a work is received, named, categorized or ignored, the intent of the author remains in some form, covers a work with fingerprints, even when that intent remains unknown.

Perhaps that last statement is paradoxical, but that will not be the last paradox on which to pound one’s head. I am apparently attracted to forms which require certain misdirected, complicated, even nonsensical or contradictory terms. Rachel Blau DuPlessis expresses this note with much clarity.

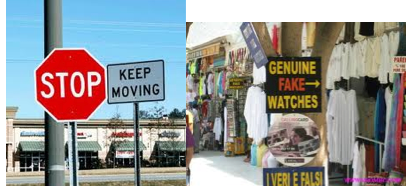

“Saying ‘poet’s novel’ evokes two very strongly tenacious words: a genre word and a practitioner word (novel/poet) that come bearing a veritable cornucopia of cultural associations and historical uses. These associations veer in different directions — narrative (perhaps even realist narrative) and person who specializes in the wifty and the lyric. Those, are, I mean, the first-thought ideological associations. Thus a ‘poet’s novel’ appears to be an oxymoron, a contradiction in terms. Which makes it precisely like a prose poem — another 2 word phrase like a contradiction in terms.”

How would one illustrate an oxymoron? Leave it to poets to be drawn to such contradictions. Part of the project of writing a poet’s novel which is so appealing is this melding of opposites. It isn’t impossible, obviously, but it evokes the allure of the impossible. When I began to write my first novel the initial incentive was, can I do this? Entering a new form, embodying a new form, as a writer is an intoxicating, perhaps daring act. Still it is a dare which is safe, because one can rip it up, literally, or use it as a first step to the next mashup piece. But even more tempting to the poet is what I’ll call the vast sea of the novel. To have characters to talk to, and real or imagined landscapes to inhabit are both incredibly compelling. Yes, one can converse within or inhabit a poem, but a novel is generally more capacious and sturdy. A novel, even a poet’s novel, can give one the sense of a roof over one’s head, which is something that many poets have had to go without. For that reason alone it is not surprising that so many poets have succumbed to this contradictory form.

The poet's novel