'Their own privately subsidized firm'

Bryher, H.D., and 'curating' modernism

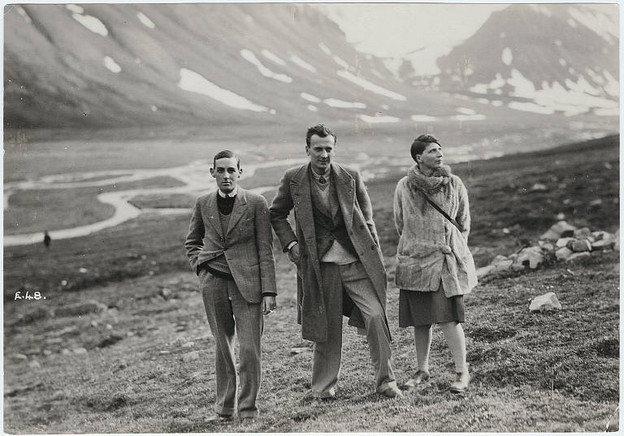

As the child of the wealthiest man in Britain, Bryher (born Annie Winifred Ellerman on September 2, 1894) occupied a unique position within the first half of the twentieth century. Her own success as a writer came later in life — her historical novels and memoirs were bestsellers in the years following World War II — but early on she used her inherited wealth to support a range of career paths: editor, publisher, and patron. Bryher early on established herself as an ardent and vocal supporter of both the creative and practical sides of literary production. She provided financial assistance to struggling poets; subsidized publishing endeavors like Robert McAlmon’s Contact Editions, Sylvia Beach’s Shakespeare and Company, and Harriet Shaw Weaver’s Egoist Press (with which she also collaborated as a contributing editor); established little magazines and presses for emerging artists and her own work; and drew on her longstanding interest in education to produce a large body of pedagogically motivated essays, reviews, and treatises on modern film, poetry, and art. Moreover, she demonstrated a willingness to challenge and transcend traditional boundaries between artistic genres — primarily literature and film — as well as those separating publisher, patron, editor, and artist.

Perhaps ironically, it is the breadth of Bryher’s contributions to the development not only of modernism as an artistic movement, but also of an audience receptive to its aesthetic and political ramifications, that has caused her to be overlooked as an artist in her own right. Jayne Marek has shown that Bryher became, in effect, an “invisible woman” through her associations with figures who were either more dynamically invested in their own personae, or who became the subjects of biographies dedicated to the construction of a mythic portrait of the era.[1] And indeed, Bryher can be hard to locate within primary accounts of her time, in part because she appears to have been so willing to recede into the background, silencing herself in ways that are themselves culturally significant. It is possible to read this silence in part through her unusual personal life, which encompassed a lifelong relationship with H.D. and two marriages of convenience to bisexual men, as well as an ardent conviction that she should have been born a boy. This personal and professional reticence has also, unfortunately, resulted in a critical invisibility that is only now being undone.

Bryher’s marriage to, and fiscal support of, Robert McAlmon — editor/publisher of Contact Editions and, with William Carlos Williams, Contact magazine — often bears the brunt of this invisibility. McAlmon’s memoirs appeared thirty years earlier than Bryher’s, and his champions were dedicated to ensuring his place within the literary mythos surrounding the writers of Paris in the 1920s.[2] Later narratives — including The Autobiography of William Carlos Williams (published by New Directions in 1967), Kay Boyle’s 1968 revision of McAlmon’s Being Geniuses Together, Barbara Guest’s 1985 biography of H.D., Herself Defined, and even Bryher’s own The Heart to Artemis: A Writer’s Memoirs (1962) — as well as academic monographs and surveys, have historically missed Bryher’s reach into nearly every aspect of transatlantic modernist literary and cinematic production.[3] To be fair, the mundanities of literary production — bookkeeping, publicity, education, audience cultivation — that make the romance of “genius” possible, and which Bryher performed and represented, are often not the most compelling elements of literary history. But they are crucial nonetheless.

Bryher’s role in ensuring the viability of modernist writers and artists has begun to be recovered, thanks to scholars such as Marek, Susan McCabe, Charlotte Mandel, and others. Their research begins to excavate the silences, illuminating the Foucauldian dictate that “There is not one but many silences, and they are an integral part of the strategies that underlie and permeate discourses.”[4] While critics like Lawrence Rainey have dismissed Bryher’s literary efforts as, at best, solipsistic — calling Brendin Press, her last publishing house, H.D.’s “own privately subsidized firm”[5] — Marek instead sees Bryher and H.D.’s partnership, in its many and shifting forms, as instrumental to “helping to push forward the frontiers of twentieth-century thought.”[6] Likewise, McCabe shows how Bryher’s archives reveal that “the unusual extent of disparagement, neglect, and discounting of Bryher has more to do with her transgressive ‘husband’ role in curating modernism than with her actual character.”[7] Bryher’s relationships with the artists she admired did cross heteronormative cultural boundaries, in ways unremarked upon yet remarkable. She independently controlled a level of wealth normally reserved for men, and adopted a traditionally “masculine” role in literary production, taking charge of the business side of the presses and magazines she worked with even as she cultivated certain artists and educated the public about them. Yet Bryher was remarkably quiet about her wealth — it garners only a sideways mention in her account of her engagement to Robert McAlmon[8] and is, at best, implicit throughout the rest of her memoirs.

Bryher’s contribution to modern art, especially that most underappreciated element of artistic success — what McCabe terms “curating,” or the cultivation of material coupled with the overt attempt to engage a willing audience with it — is best understood by examining her publishing and editing career in toto, as deeply influenced by her personal idiosyncrasies and also marked by both profound silences and moments of astonishing revelation and action. This occurs most clearly when Bryher blurred the boundaries between her personal relationships and her public/professional endeavors, a pattern that can be seen as partially responsible for the ways in which her work has been dismissed as paternal or solipsistic. Rachel Blau DuPlessis’s early work on H.D. represents an important first step toward acknowledging Bryher’s presence within H.D. scholarship and, more broadly, an emergent, alternate modernism that resisted the dominant, masculine ethos of Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot. Blau DuPlessis credits Bryher with helping to develop parts of the poet’s mercurial sexual persona, wondering in a 1979 article if “Perhaps [H.D.] felt guilty to be so happily involved in a world made up of women exclusively — she, her daughter Perdita, and Bryher appear as a kind of triple goddess in some of her late dreams — and had to compensate by torturing herself with thralldom to men.”[9] Twenty years later, DuPlessis notes that Bryher’s presence was an essential part of H.D.’s “complex relational life,” suggesting her centrality within H.D.’s career as a whole.[10] Recovering Bryher-as-muse (of a sort) was a crucial beginning to recovering the complicated nature of a poet like H.D., yet because H.D. is the focus, Bryher’s presence is primarily that of helpmeet or “midwife” of the poet’s genius, rather than an active and influential player herself. Building on this essential work, I want to suggest an expanded vision of the world that these women created together, and its ramifications for the dynamic literary landscape of the early twentieth century.

Bryher’s contributions have been historically difficult to parse in part because she herself is so mercurial, shifting from intimate to public roles with the same people, often within the same circumstances. Lauren Berlant and Michael Warner identify the critical/social impulse to find “a structural differentiation of ‘personal life’ from work, politics, and the public sphere” as distinctly heteronormative, an attempt to reinscribe “public” heterosexuality onto queer relationships.[11] They argue that “[T]he normativity of heterosexual culture links intimacy only to the institutions of personal life, making them privileged institutions of social reproduction, the accumulation and transfer of capital, and self-development.”[12] While much of the early feminist recovery work honored the primacy of the H.D.-Bryher relationship (or her ties with other women and men), in so doing it often glosses the influence she had upon the readers who supported the writers she loved. Bryher transgressed the distinction between professional and personal boundaries fairly consistently, bringing intimates into her public sphere and bestowing professional favors on close friends. Only by taking seriously the delicate balancing act between privacy and revelation, personal life and professional life, that Bryher maintained can we begin to understand how she so profoundly affected the international reception of modernism in the years following World War I.

Bryher’s penchant for transgression was apparent from the start: The protagonist of her early novel, Two Selves (1923), wrestles with the certainty that she was meant to be a boy.[13] This outcast sensibility informed her interest in art as a revolutionary mode of expression and social change, one that she enacted specifically by publishing three novels before her twenty-ninth birthday. It also provides insight into her collaboration with McAlmon for Contact Editions, and the energy and momentum that Bryher inspired in him. McAlmon’s early letters to Bryher revel in their platonic relationship and shared aesthetic sensibility. In an typical missive from 1921, he questions her taste in poets, in this case Marianne Moore, and then enthusiastically compliments her:

[Marianne Moore] will matter as a piquant idea — a closeted intellect I think …. I can’t know whether people like that have any urgent life in them, or not …. [handwritten on margin:] As Mrs North said “You’ll be a great poet.” You are now one of about 5 I know about who do not make a mannered impression of writing. That’s real achievement.[14]

Such conversation repeats throughout his correspondence, mixing critical debate with admiration for her talent, and gratitude for her support. He writes, “O I’m liking myself these days Bryher — and I’m doing writing I’d not have done for years, perhaps never, if I had stayed in that damned New York. You’re to thank for that,”[15] suggesting that he found liberating the fact that the marriage was, in his own words, “legal only, unromantic, and strictly an agreement.”[16] Indeed, these limitations perhaps enabled a more equal exchange of ideas, one unhindered by the traditional social roles Bryher challenged, and ultimately rejected, throughout her life.

The “invisibility” that Marek notes as symptomatic in early treatment of Bryher indicates a pattern in Bryher’s own life that first surfaced in her personal relationships, from as far back as childhood,[17] and revealed itself publicly almost as soon as she entered society, continuing throughout her considerable career. It also manifests in early critical work, downplaying Bryher’s impact by inadvertently concealing ways of understanding the role of people like her, who were able to exploit their own resources in service to art, by working outside the boundaries of traditional partnerships.

“You want something in poetry and in life that I want too”

By the time she became involved in Contact Publishing, Bryher had already established her engagement with the burgeoning literary and artistic movements of the 1910s. Her interest in poetry, and the possibilities of language and art, began long before her involvement with McAlmon — though it was, even early on, inextricably bound up with her personal development and sense of identity. A devoted reader, she recalls in The Heart to Artemis her discovery of the French symbolist poet, Stéphane Mallarmé, and simultaneous introduction to the transatlantic modern poets:

I do not know how I should have lived if it had not been for one of those little magazines that, as Gertrude Stein was fond of quoting, ‘have died to make verse free.’ It was Poetry and Drama, edited by Harold Monro .… F. S. Flint had written articles on modern French poetry and I found in them for the first time the magic word ‘Mallarmé.’[18]

From there, she found Pound’s seminal Des Imagistes, which led her to Amy Lowell and, ultimately, H.D., Harriet Shaw Weaver, and Marianne Moore. Fifty-three years after the event, Bryher wrote of the appeal that vers libre and imagism held for a fifteen-year-old would-be poet on the brink of self-revelation and artistic inspiration: “I was discontented with traditional forms but this was new …. [The artist] must be in advance of his time and as to know is to be outcast from the world, why should he expect recognition?”[19] In this moment, she establishes the themes that resurfaced throughout her life, most especially the ways in which feeling “outcast from the world” fed the literary and artistic innovation of an entire movement. Bryher engages the trope of outsider-as-visionary repeatedly in her memoirs, embracing the overlap between personal identity, political engagement, and professional/artistic development. Indeed, this tension was central to her unusual marital-business arrangements, and to her willingness to transgress the standard editorial role in relation to the artists she supported.

Bryher’s editorial relationship with Egoist Press began in 1918 — three years before her marriage to McAlmon — when H.D. introduced her to Harriet Shaw Weaver. She went on to write reviews for The Egoist magazine, and Weaver invited her to translate Antipater of Sidon’s “Six Sea Poems” for The Poets’ Translation Series.[20] H.D. introduced her to Marianne Moore as well, and following her 1921 marriage to McAlmon, Bryher worked with Weaver to publish both Marianne Moore’s Poems and H.D.’s Hymen. The books were printed in a limited edition of 300, the entirety of which Bryher bought and then left with Weaver to resell. While this might seem a baffling action, Bryher’s sponsorship of these two titles represented a crucial element of each poet’s initial reception.

In her analysis of the professional relationship between Marianne Moore and T. S. Eliot, Sheila Kineke defines “literary sponsorship” as a useful framework for understanding modernist patronage and publication, particularly among women. She notes multiple definitions of the term “sponsorship” within the Oxford English Dictionary, including the commercial aspect (“one who pays or contributes towards, the cost of a broadcast programme or other spectacle … in return for commercial advertisement”) and the “agonistic” (“one who stood surety for the appearance and good faith of either party in a trial by combat.”)[21] Commercially, Bryher stood to gain from the success of Poems and Hymen — if not financially, then by a more widespread recognition of artists she championed and, secondarily, acknowledgement of her own abilities as editor. Thus what might be cast as an effort to fetishize or cloister certain authors can also be understood as a way to guarantee audience. Bryher’s willingness to contribute to the publication of Poems and Hymen, and her decision to “stand surety” for their success, allowed Egoist Press to keep costs low for potential buyers. Through Bryher’s sponsorship, the books quite literally paid for themselves. While any poet might hope that her work would be organically discovered, read, and celebrated, the realities of the publishing world in the early twentieth century — particularly for practitioners of a new and daring poetics — often necessitated subsidization.

It matters, as well, that H.D. and Moore were among the first two poets Bryher “published.” Her ardent support of H.D. was perhaps to be expected: Their personal relationship grew out of Bryher’s admiration for H.D.’s poetry, and by the time Hymen was published, Bryher had nursed H.D. through a nearly fatal bout of flu and the birth of her daughter Perdita. With Moore, the personal/professional relationship was more complicated. Bryher and H.D. were Moore’s earliest champions, helping bring her work to the attention of critical supporters like Eliot, Williams, and McAlmon.[22] While H.D. participated fully in the production of Hymen, Bryher’s friendship with Moore empowered the former to overrule the latter’s resistance to publication. Accounts of this dispute range from the resentful[23] to the conspiratorial, but Elizabeth Gregory offers perhaps the most balanced assessment, arguing that Moore’s resistance grew out of an “overall critique of the literary superstructure that her work effects.”[24] Further, she claims that the publication of Poems engendered a response that

combined anger … with gratitude …. Though Moore also took steps to encourage publication of her work, her qualms (more than mere modesty) seem consistent with her revisionary practice in their questioning of the privileged and inviolable status of established texts ….”[25]

In other words, Moore’s resistance was not to publication per se, but to the fixedness such undertakings implied.[26] By publishing a limited edition through a British press, Bryher ensured that Moore could revisit, revise, and republish the poems in later editions and versions, most notably the American Observations, a collection that included much of the work in Poems but published three years later, at Eliot’s urging.[27] Bryher’s willingness to refigure the relationship between poet and publisher, motivated by the personal as well as professional alliances that marked her career, eliminated the more mercenary aspects of publishing, and made it possible for her closest friends (Moore, but also Weaver and H.D.) to work unencumbered.[28]

The chivalric origins of the “agonistic” facet of sponsorship — the champion standing for and defending his familiar — complicate and expand on assessments of Bryher’s patronage as well, specifically through her written reviews. Like Eliot and others, she had no qualms about reviewing her friends. Indeed, one might excuse the uncomfortable ethical propriety of reviewing books one has paid to publish by acknowledging its long tradition within modernist literature, and the fact that Bryher’s wealth obviated the need to sell the books in order to become or remain profitable. In Harriet Monroe’s “symposium” on Marianne Moore, published in the January 1922 number of Poetry, Bryher’s review of Poems reveals both her literary fluency and her efforts to guarantee Moore a wide readership. Monroe describes Bryher (perhaps disingenuously) as a “more moderate admirer” of Moore’s, though the review itself is glowing and poetic in its own right:

This volume … is the fretting of a wish against wish until the self is drawn, not into a world of air and adventure but into a narrower self, patient, dutiful and precise. “Those Various Scalpels” is … as brilliant a poem as any written of late years …. [Moore’s] Poems are an important addition to American literature, to the entire literature of the modern world.[29]

Bryher engaged both the literary and commercial aspects of publishing, doing what she can to establish Moore’s first book as “an important addition to American literature” and situating the poet among those more commonly reviewed in Poetry at the time (Eliot, Pound, H.D., Lowell). It is, in many ways, a nascent form of support and patronage that Bryher would later develop throughout her tenure as publisher/editor of various magazines and presses.

“I would start a film club”: Crossing boundaries in Close Up

By 1927, Bryher had divorced McAlmon and married Kenneth Macpherson, a move that allowed her to more fully explore the patron/publisher roles she had begun to inhabit during her first marriage. With Macpherson and H.D., Bryher established a complicated, triangulated personal relationship — the bisexual Macpherson and H.D. were briefly romantically involved, while Bryher and Macpherson legally adopted Perdita, H.D.’s daughter from an affair with the composer Cecil Gray — which found creative fruition in Close Up magazine, the first film magazine in English, and the film and publishing company POOL. Close Up provided a forum for the pedagogical mode that Bryher embraced from an early age: Her theories of education achieve full expression in the pages of this magazine, devoted as it is to explicating both a modernist aesthetic and a burgeoning and at times baffling new medium. Close Up also established an aesthetic and intellectual connection between the art of cinema and the literary experimentation undertaken by modernist poets and novelists, particularly women. This connection was cultivated and influenced by Bryher’s engagement with both genres, her willingness to put writers and filmmakers into dialogue with each other, and her continued publication of poets as film theorists (and vice versa). The magazine provided a platform through which Bryher first engaged what Celena Kusch calls her “transnational cultural project … shaping the definition of modernism” across national borders.[30] Through Close Up, Bryher created connections between modernist artists in multiple genres, a project that would come to define her influence on the era as a whole.

Bryher, H.D., and Macpherson launched POOL and Close Up with the July 1927 number. Close Up was initially a monthly journal intended to “transform the cultural topography of the cinema and its future,”[31] though as the years went on its frequency diminished to quarterly, and it closed in 1933. While Macpherson was the editor in chief and established the philosophical underpinnings of the journal, Bryher took on the managing editor role, running the day-to-day aspects of the magazine and often taking charge of contributors and content. Close Up performed several important functions for Bryher as editor and publisher, and as a cultural avatar. Anne Friedberg argues that

[i]n retrospect, the body of writing in Close Up appears as its own form of “literary montage” — a serial project with the random architecture of juxtaposition, an exhibit of documents which offers the contemporary reader an extensive tour of the ardent debates about cinema as it emerged as an aesthetic form.[32]

Close Up thus embraced a distinctly modernist approach to both intellectual engagement and the cultivation of the reader. This embrace of “montage” helped justify her habit of putting poets and filmmakers into conversation with each other and the reader, placing multiple points of view and theories in close proximity in order to make them new, strange, or provocative in ways that recall both avant-garde filmmakers and the fractured, multifaceted element of modernism more generally. At the same time, Close Up was an organ for publishing writers Bryher personally and publicly championed, giving them room to develop ideas in multiple genres within a supportive environment.

Throughout her tenure as publisher and editor of Close Up, Bryher’s willingness to break the boundaries between art and politics surfaced in her encouragement of her favorite artists to push beyond their own generic ideals. Writers and poets tackled film criticism and theory, while filmmakers contributed poetry and short essays. H.D.’s contributions to Close Up provide a useful example of this: She submitted eleven articles during the first two years of the magazine’s existence, along with poetry. (Perhaps unsurprisingly, her efforts dropped off once the magazine became embroiled in debate about sound and film, leaving behind the more visual elements of the genre.)[33] H.D.’s engagement with film was, as Laura Marcus argues, “in many ways idiosyncratic, to be understood as an aspect of her broader concerns with language and symbol, psychoanalysis, mysticism and spiritualism, classicism and the celebration of women’s beauty and power.”[34] Bryher’s willingness to publish her “idiosyncratic” and, at times, digressive work in a magazine so deeply devoted to both the theory and technical exploration of film demonstrates her personal/professional commitment to H.D.’s artistic development, even if it occasionally wandered from the overt mission of the journal.

In the first issue, July 1927, H.D. published two pieces: a poem, “Projector,” and the first of a three-part film critique, titled “The Cinema and the Classics.” These two works inform each other and frame the number — the critique is the first “feature” and the poem is the last, creating a visual break between the significant body articles and the “Comments and Review” and “Advertisements” departments. H.D.’s relative inexperience with film (particularly as compared to Macpherson or even Bryher) is less important than her desire to write about it, and her criticism introduces ideas that echo, and are echoed in, her poetry.[35] The first installment of “The Cinema and the Classics” is subtitled “Beauty” and H.D. dispenses quickly with movies per se, beginning her second paragraph with the dismissive, “So much for cinema.”[36] Better, she argues, to think of film in terms of an endangered experience of beauty, specifically one that enables something like transcendence: “Anyhow it is up to us, as quickly as we can, to rescue this captured Innocent [film] … stepping frail yet secure across a wasted city. … Beauty, among other things, is reality, and … beauty herself, Helen of Troy, rises triumphant and denounces the world for a season, then retires.”[37] Film becomes a metaphor for resistance to war’s ugliness and brutality, a capricious art capable of instigating fleeting moments of “triumph” that recall an epic age of beauty and glory.

These images appear again in “Projector,” a poem that, while named for a cinematic technology, quickly leaves behind these mechanical roots in favor of a meditation on light, mythology, and transcendence. Here, film is invoked primarily in the ways that H.D. conjures images — shrines, gateways, markets, cross-roads — recalling the frenetic jump-cut of the cinematic frame. As in a film, the images work together to evoke something bigger, epic, transcendent: the light from the projector bulb morphs into “a king of blazing splendour and of gold,”[38] an image that reappears throughout lines that juxtapose pomp and majesty, gold and light, mythos and spiritual revelation. Ultimately, the projector gives a “vision” that offers “fresh hope” for “weary eyes that never saw the sun fall in the sea / nor the bright Pleadiads [sic] rise.”[39] The lyricism of H.D.’s verse and the poetics of her criticism are markedly different from the pedagogical tone of Bryher’s editorials or Macpherson’s theoretical examinations of film. Instead what emerges is a poet working through her own project, using film as one source of inspiration in her own engagement with poetry and spirituality.

These pieces appeared in the first issue of Close Up but they are indicative of the pattern of H.D.’s contributions to the magazine, which themselves reveal Bryher’s own priorities. One of H.D.’s final essays for Close Up, “An Appreciation,” in the March 1929 number, continues her montage style of image-driven, lyrical criticism, situating film critique within the poetic discourse previously established by her oeuvre. Ostensibly a celebration of the career of the actress Louise Brooks, H.D.’s rumination instead dwells lovingly on Brooks’s eating habits, her attitudes at lunch, and a brief conversation between her and G.W. Pabst.[40] H.D. recalls the merits of Christmas pudding,[41] and digresses on emotions and art, calling art “a sentiment that is never called forth and never inspired and never made to blossom by technical ability, by sheer perfection of a medium, by originality and by intellectualism, no matter how dynamic …”[42] But we must wait three pages for H.D. to even mention a specific film, and then it is not Brooks but Pabst whom she praises, shifting the entire focus of the critique as fluidly as she earlier moved from pudding to beauty.

Thus film became one more medium in which H.D. could begin to articulate a philosophy of art as “universal,” capable of, as Marcus argues, “bridging national differences or, at least, … allowing for a clear, undistorted perception of the terms of such differences.”[43] By providing an outlet for H.D.’s idiosyncratic film writings, Bryher encouraged the poet to venture into new forms, new genres, and new ideas by ensuring an audience for them. She also made explicit her own connection to, and support of those ideas. The ease with which she incorporated H.D.’s cross-genre experimentation into the theoretical and technical discourse of Close Up is indicative of Bryher’s own fluidity in regard to her role as publisher, editor, patron, and friend.

“Responsibility for the future”: Publishing during the wars

Bryher’s influence on Close Up was visible until it folded in 1933. Unwilling, perhaps, to stray too far from the world of literary publishing, she started Brendin Publishing Company shortly thereafter. Brendin specialized in limited editions of books, including a lavishly illustrated edition of Marianne Moore’s The Pangolin and Other Verse in 1936; the 1937 Cinema Survey pamphlet by Bryher, Robert Herring, and Dallas Bower; an illustrated edition of H.D.’s children’s book, The Hedgehog; and two collections of H.D.’s poetry intended as for “private circulation” among their friends.[44] These limited-edition books were more than mere frivolity, however, despite the fact that they were printed at the height of the Depression in England, as the continent edged perilously close to war. Even during Britain’s increasingly difficult national and political situation in the 1930s and 1940s, Brendin remained able to produce books, and as a result, helped keep literary production alive in England through World War II.[45] Bryher’s influence is most apparent in her acquisition through Brendin of Life and Letters, at that time a floundering but respectable literary magazine that she retitled Life and Letters To-Day. Critical interpretation of this journal tends to focus on Bryher’s publication of twenty-three of the thirty-one new poems H.D. wrote between 1931 and 1950 in its pages, rather than its lengthy run and international scope.[46] There is little evidence, however, to support the idea that Brendin or Life and Letters To-Day were H.D.’s vanity presses, gifts bestowed by a paternalistic sponsor upon a pet poet; rather, they mark a triumph of Bryher’s skill as editor and publisher, making accessible a wide range of international voices and genres to readers all over the world, and provide a fitting conclusion to her publishing career.

With Life and Letters To-Day, Bryher managed to create and keep viable[47] a literary magazine that explicitly connected her intimate friends and personal aesthetic philosophies to an international community of modernist artists, allowing British readers to experience a range of ideas even as World War II loomed on the horizon. She took over the publication of the magazine in 1935, with her friend and Close Up contributor Robert Herring. The journal had been in existence at that point for seven years, a vehicle primarily of the Bloomsbury group of writers and artists. In a letter from Virginia Woolf to her sister, Vanessa Bell, in February 1928, Woolf details the initial aim of the magazine and its editor, Desmond MacCarthy:

Desmond has been given £6.000 by Oliver Brett to start a monthly magazine with. How bored you would be to hear all of us authors chattering about it! — not that it will ever come out, but if it did come out it would be the most brilliant, the most advanced, the best said paper in the world — Also it would make Desmond’s fortune, so he says.[48]

While the magazine did manage to be born, MacCarthy never achieved the wealth and fame (let alone the superlatives) he hoped for. In part, his own idiosyncrasies may have doomed Life and Letters: his insistence on reviews of established writers; his love of detective fiction; and his embrace of the Bloomsbury writers, who by then were no longer quite so cutting edge.[49] Though MacCarthy published notable authors like Vita Sackville-West, Bertrand Russell, and Robert Graves, he was unable, finally, to establish a coherent identity or aesthetic. The magazine underwent significant financial difficulty and two changes in editorial staff and ownership before Bryher’s school friend and fellow writer, Petrie Townshend, alerted her to the possibility of buying it for £1,500 in April 1935. Bryher appointed Herring, her friend and collaborator from Close Up, and Townshend (for two issues) to handle what she called the “hack work” of day-to-day editing, while she solicited manuscripts and shaped the editorial vision.[50]

This shift in the roles Bryher adopted is notable after her professional collaboration with Macpherson, in which she ably handled the “hack work” to support Macpherson’s vision. Unlike Macpherson, however, Bryher’s name did not appear on the masthead of the newly revamped Life and Letters To-Day, despite her editorial input. Instead, the Table of Contents reads like a Who’s Who of those writers and artists, particularly filmmakers, she worked with throughout her life.[51] The last issue of Life and Letters under Hamish Miles (who took over from MacCarthy in the last years of their involvement with the magazine) includes writers like Roland Lushington and Denis Ireland, and is fronted by an ad for the Everyman’s Library editions of Henry James and G.K. Chesterton.[52] Bryher and Herring’s first issue, on the other hand, bears a remarkable resemblance to the contributor lists of Close Up and even Contact and Contact Editions: Mary Butts, Osbert Sitwell, Siegfried Sassoon, Gertrude Stein, and Havelock Ellis fill its more than 200 pages, and the facing ad signals that the following issue will feature Wallace Stevens, Hanns Sachs, and Jean Prevost.[53] There is a “Cinema Section,” of course, with articles by Sergei Eisenstein and Robert Herring, and an extensive “Reviews of Books” section which in later issues becomes varied enough to warrant categorization by country of origin. Bryher even titled the current events section “News Reel,” a nod to her and Herring’s cinematic backgrounds. Later issues included Dylan Thomas, Dorothy Richardson, Marianne Moore, a very young Elizabeth Bishop, and Thomas Mann. Renata Morresi argues that

Life and Letters To-Day aimed at becoming a centre for cultural debate on literature and the arts, promoting young talented writers, and, in general, at being a crucible for the new, which included new sciences such as psychoanalysis and anthropology and new arts such as cinema.[54]

In this respect, it much more closely resembled other little magazines that preceded it (The Dial, Poetry, The Little Review, The Egoist), than it did a vanity publishing outlet. Bryher’s tenure as publisher/editor lasted fifteen years, rivaling all but Harriet Monroe at Poetry in terms of the length of her run — and she did it under arguably more difficult circumstances. Bryher’s Life and Letters To-Day not only stayed afloat until 1950, it did so as bombs destroyed three different office locations — and sold out month after month.[55]

Although Bryher’s name is not on the masthead as editor, her influence can be seen throughout the magazine. The first (unsigned) editorial in the first issue details the magazine’s mission:

We are aware of our debt to the past. We are conscious also of responsibility to the future, and it is because of the need to maintain an outlet for the non-commercial work of our time that we are trying to give “Life and Letters” further life. it will, we are told, be uphill work … we would declare that any bias we have is not towards experiment for its own sake, but to unrecognised achievement. We incline to young writers more for what they may do, given outlet, than for what they have done.[56]

Herring may be the presumptive writer, but the language echoes not only Bryher’s own syntax — her writings for the magazine included reviews, articles, and a serialized novella — but also the philosophy of patronage mentioned briefly in her memoirs. In The Heart to Artemis, she recalls her father’s admonition to support only those artists who are still living (for they need the money), and his willingness to pay for “some of my incredibly bad verses to be printed.”[57] One might see her father’s willingness to blur filial and professional boundaries as the beginning of Bryher’s own such efforts, and it echoes in the “Editorial” — particularly the determination to support what young artists “might do” rather than what “they have done.” Bryher herself proudly recounted her contributor list in The Days of Mars, her memoir of the war years:

Besides contributions from the Sitwells, H.D., Elizabeth Bowen, Dylan Thomas, Vernon Watkins, Alex Comfort and many other writers, we printed, I believe, the first story by Sartre to be translated into English and an early tale by Kafka.[58]

Her deep commitment to an international scope of literary art is apparent as well. Celena Kusch has argued that Bryher was responsible for “connecting H.D. and many of her American colleagues with continental artists and intellectuals”[59] in the early parts of their respective careers; with Life and Letters To-Day, that commitment to a transnational community of artists took concrete form. Kusch reads the first issue’s “Editorial” as indicative of Bryher’s underlying fascination with the “youth” and possibility represented by the idea of America.[60] More than that, it represents the creation of a truly international space, where multiple languages and political beliefs, strangers and intimates, can mingle under the umbrella of modern art. Bryher kept Life and Letters To-Day going during the War, and was committed to its availability around the world, ensuring that her audience could consistently participate in the artistic conversation. The magazine represented the culmination of a lifetime of dedicated support and encouragement for the artists Bryher so admired and the readers she so ardently hoped to cultivate for them.

The transnational element of Bryher’s editorship is a useful place to conclude an analysis of her work within the development of an audience for modernist poetry. Rather than simply seeking larger outlets for the writers published therein, Bryher explicitly saw the development of international relationships, and the education of her readers, as a crucial aspect of her role as publisher/editor. Her own restless relocation,[61] and her sense that she didn’t quite belong to any one country until she staked her lot with Britain during the Blitz, reverberates throughout the magazine’s attempts to connect international empathy, antifascism (or perhaps antinationalism), and artistic engagement. In the Summer 1937 issue, Bryher published a piece titled “Paris 1900,” in which she claims to have “geographic emotions,” that is, a natural empathy with cities — and all the history, social heterogeneity, and motion that they imply — rather than individual people.[62] Implicit within this is the idea of committing to communities rather than nations, and to connecting those communities through wanderlust and international engagement.

In the Autumn 1936 issue, a year before Bryher’s “Paris” piece, the opening “Editorial” established the political and historical ramifications of this fluidity, inviting readers to join a community invested not only in art but also in world politics and social development. Employing a universal and again unsigned “we,” the piece addresses the Spanish civil war and launches an interrogation of the role of art within international dialogues, which ultimately continues until the magazine abruptly ceases publication in 1950. It begins as, quite literally, a call to arms:

A year ago we expressed out intention of being non-political in these pages.… But a year ago is a year ago, and it would be useless to maintain now that Spain’s civil war is none of our business. It is everyone’s business. We hope that we speak for our readers as well as for our authors when we say that we consider it impossible to go to press without paying tribute to the courage of the Spanish people fighting in support of their government.[63]

“We” goes on to criticize the coverage of the war in the English and French press, decrying the media’s painting of the loyalists as “really the rebels,”[64] and warning that such media might be a harbinger of what may come to Britain or France, should a fascist force take over. Moving quickly from politics to the efforts of the International Association of Writers in Defence of Culture to establish the freedom of the press even during times of conflict, the “Editorial” provides the first instance in which Bryher and Herring were explicit about the connection between a vital literary culture and liberty:

But because we ourselves, with our translations and articles from other countries, attempt to keep the world open instead of a collection of closed nationalistic compartments, we do stress that writers such as Gorki when he was alive, Gide, Karel Kapek, Heinrich and Thomas Mann … were alive to the necessity of urging their colleagues to make a stand for those principles of humanity for which they are, or should be, the spokesperson.[65]

Life and Letters To-Day became, in many senses, a beacon of international creativity and audience engagement, an outlet for the editors to educate, empower, and ultimately plead with their audience to take part in the growing unrest around the world. This is particularly true of Bryher, who saw herself at the front lines of a war that no one else would admit was coming. In The Heart to Artemis she recalls living in Switzerland, where she edited Life and Letters To-Day via post and used her home to help Jewish artists flee an increasingly hostile Germany and Austria: “I warned the English privately and also in print. They called me a warmonger and jeered at me for my pains .… I remain ashamed of the majority of my fellow citizens and convinced that apathy is the greatest sin in life.”[66] This sentiment comes through clearly in both the “Editorial” of 1936, and in future issues, a sense that the readers must be active, must be cognizant of, and work to defend, the connection between artistic freedom, international peace, and justice. Most of all, Bryher here enacted an active rejection of the boundaries between such ideals, blurring the lines between art and politics much as she blurred the lines between intimate and professional engagement.

Life and Letters To-Day (by that time titled simply Life and Letters again) abruptly closed in 1950, following a notice at the end of the May 1950 number stating simply: “It is regretted that it has been found impossible to continue LIFE AND LETTERS. The review will therefore be suspended after the June issue, which completes the present volume. The balance of subscriptions will be refunded in due course.”[67] The brevity was likely perceived as jarring for readers, for the next (final) issue features a lengthy apology and explanation for the decision. The June 1950 leader begins:

With this number, as announced in the May issue, we suspend publication. That notice, occurring as it did on the last page and consisting of only three and a half lines, may have seemed somewhat curt. For that, I would apologize. I intended no discourtesy to readers but sought, rather, not to distract attention from the Norwegian authors, whose number it was, by discoursing unduly on so personal or domestic a matter as our cessation.[68]

The reasons Bryher gives for shutting down the magazine will not be unfamiliar to scholars of, or participants in, small-press publication: loss of money, lack of time, instability. I name Bryher here as the single author of this unsigned “Editorial” — the first and only to employ the singular “I” rather than “we” — in part because the focus is so clearly on the financial aspects of publication, but also because she quickly turns attention not only to the readers, writers, and staff, but also to the behind-the-scenes companies that enabled literary production. It is here that she adopts the plural “we”:

Looking back, indeed, the wonder would seem less that we end now than that we did not before — at almost any time in the last ruffled decade-and-a-half of wars, cold wars, and wars of nerves; of abdication and elections; of restriction, regimentation, and reaction. But I do not propose to look back .… We have not lacked support, and I would like here to thank not only readers and writers, but also publishers, agents, and the trade for their unvarying help …[69]

This acknowledgement of the workhorses of the publishing industry — in the same breath as the creativity they make possible — was typical of Bryher’s own sense of the debt owed to the people behind the legends, a tacit awareness, perhaps, of her own place within that circle. Indeed, in The Heart to Artemis, she recalls meeting Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas, whom she much preferred: “[I]t was Miss Toklas whom I loved. She was so kind to me. Perhaps this came from her long practice as Gertrude wrote ‘of sitting with the wives of geniuses.’”[70] As one who had long been regarded as a “wife” of genius — whether supporting Robert McAlmon, H.D., or Kenneth Macpherson — Bryher might easily have seen herself allied as strongly with the businessmen as with the artists. After folding Life and Letters, Bryher went on to develop her own creative impulses, writing a series of bestselling historical novels and three memoirs, and formally ending her position as an editor and publisher (though not ceasing her financial support of individual artists). The final “Editorial” thus provides a fitting coda to a publishing career that spanned three decades and crossed multiple boundaries, upsetting social conceptions of personal and professional relationships; creating a critically empowered readership; and ultimately redefining the role of the editor/publisher/patron in the first half of the twentieth century.

1. Jayne Marek, Women Editing Modernism: “Little” Magazines and Literary History (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1995), 101.

3. See Kay Boyle’s savage characterization of the quiet heiress as “infantile” in Being Geniuses Together (New York: Doubleday and Company, 1968), 53, or Guest’s portrait of a pathologically controlling, and frustratingly sullen, misanthrope in Herself Defined: The Poet H.D. and Her World (New York: Doubleday, 1984), 115. Susan Stanford Friedman offers some insight into Guest’s characterization by demonstrating that her representation of H.D. is one of “a fragile and nervous Circe who draws everyone into her net.” See “Review: H.D.,” Contemporary Literature 26, no. 1 (Spring 1985): 109.

4. Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality, Volume 1: An Introduction, trans. Robert Hurley (London: Penguin, 1990), 27.

5. Lawrence Rainey, Institutions of Modernism: Literary Elites and Public Culture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998), 153.

6. Marek, Women Editing Modernism, 102.

7. Susan McCabe, “Bryher’s Archive: Modernism and the Melancholy of Money,” in English Now: Selected Papers from the 20th IAUPE Conference in Lund 2007 (Lund, Sweden: Lund University Press, 2008), 119. Emphasis mine.

8. Bryher, The Heart to Artemis: A Writer’s Memoirs (Ashfield, MA: Paris Press, 2006), 239.

9. Rachel Blau DuPlessis, “Romantic Thralldom in H.D.,” Contemporary Literature 20, no. 2 (Spring 1979): 189.

10. DuPlessis, “H.D. and Revisionary Myth-Making,” in The Cambridge Companion to Modernist Poetry, ed. Alex Davis and Lee M. Jenkins (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 114.

11. Lauren Berlant and Michael Warner, “Sex in Public,” Critical Inquiry 24, no. 2, “Intimacy” (Winter 1998): 553.

13. Two Selves begins with an evocation of what we might now call transgenderism: “Two selves. Jammed against each other, disjointed and ill-fitting. An obedient Nancy with heavy plaits…. A boy, a brain, that planned adventures and sought wisdom.” Bryher, Two Novels Development and Two Selves, ed. Joanne Winning (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2000), 183.

14. Robert McAlmon, letter to Bryher, 1921, 1. Bryher Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

16. Quoted in Boyle, Being Geniuses Together, 45.

17. In The Heart to Artemis, Bryher recalls meeting Doris Banfield, the girl who took her “all over the [Scilly] islands” (148). They “were inseparable” and “only [grew] nearer to each other throughout the intervening years” (148). The island was, of course, Bryher Island in the Scillies, the name she ultimately adopted as her own.

18. Bryher, The Heart to Artemis, 180.

20. Marek, Women Editing Modernism, 116

21. Sheila Kineke, “T. S. Eliot, Marianne Moore, and the Gendered Operations of Literary Sponsorship,” Journal of Modern Literature 21, no. 1 (Summer 1997): 123.

22. Indeed, while McAlmon found Moore personally aloof and naïve, and felt her poetry “cold,” he did publish her work in Contact at Bryher’s suggestion.

23. George Bornstein argues that the publication of Poems was a misguided failure, as Moore repeatedly expressed unhappiness with that edition. See Material Modernism: The Politics of the Page (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 140.

24. Elizabeth Gregory, introduction to The Critical Response to Marianne Moore (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2003), 4.

26. Letters from McAlmon at the time suggest few people saw Poems as contrary to Moore’s wishes. He writes, “What do you hear from Marianne? I hope she isn’t irretrievably offended by publication of her book, anti —” implying that her unhappiness was more performative than serious (Robert McAlmon, letter to Bryher, 1921, 1).

27. Andrew J. Kappel, “Presenting Miss Moore, Modernist: T. S. Eliot’s Edition of Marianne Moore’s ‘Selected Poems,’” Journal of Modern Literature 19, no. 1 (Summer 1994): 130.

28. In The Heart to Artemis, Bryher discusses Moore and H.D., and indeed all of the Paris set, almost entirely in terms of friendship and conversation; she mentions little of the financial aspect of these relationships.

29. Harriet Monroe, “A Symposium on Marianne Moore,” Poetry 19 (January 1922): 208.

30. Celena Kusch, “‘Not a Continent I Dreamed About’: Bryher’s Circle Between the Wars” (paper presented at the Modernist Studies Association Annual Conference, Montreal, Quebec, November 6, 2009), 2.

31. Anne Friedberg, “Introduction: Reading Close Up, 1927–1933,” in Close Up 1927–1933: Cinema and Modernism, ed. James Donald, Anne Friedberg, and Laura Marcus (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1998), 3.

33. Marcus argues, convincingly, that when H.D. did write about sound, she “contrast[ed] it (for the most part unfavourably) with the ‘masks’ of silent cinema which, like those of Greek drama, conceal … a mystery and a vision destroyed by the ‘mechanical,’ overtly automated technologies of ‘movietone’ sound” (“Introduction: Reading Close Up,” 101).

34. Laura Marcus, “Introduction: The Contribution of H.D.,” in Close Up 1927–1933: Cinema and Modernism, 98.

35. Marcus notes, “the interplay between an aesthetics of formal restraint and one of emotional, spiritual, or ‘psychic’ transcendence, between holding back and going beyond, runs throughout H.D.’s film writings.” “Introduction: The Contribution of H.D.,” 97.

36. H.D. “Cinema and Classics: Beauty,” Close Up 1, no. 1 (July 1927): 23.

38. H.D., “Projector,” Close Up 1, no. 1 (July 1927): 47.

40. H.D., “An Appreciation,” Close Up 6, no. 3 (March 1929): 56–57.

41. H.D. spends much time on the food: “Louise Brooks said that the Christmas pudding she had had in London was not flat, but round — basin shape. That she had liked it very much, and lived on it for a week.” “An Appreciation,” 57.

43. Marcus, “Introduction: The Contribution of H.D.,” 104.

44. Rainey, Institutions of Modernism, 153.

45. In Material Modernism, George Bornstein argues that such small, limited editions played “an important role in modernist dissemination during the 1910s and especially the 1920s,” and that Bryher’s use of her wealth to continue the tradition “gestured toward an alternate economic order to the one that had led to the Depression itself” (112–13).

46. Even H.D. biographer Barbara Guest saw the journal as a vanity press for the poet, writing, “If H.D. were worried about her neglect by the literary scene … Bryher would provide a publication in which H.D.’s poetry and prose could once more find its readers.” Herself Defined: The Poet H.D. and Her World (New York: Doubleday, 1984), 232.

47. Bryher’s prescient decision to stock up on paper in 1938 led to accusations that Life and Letters To-Day was hoarding. They were forced to share with other, “less thoughtful” publications as the War dragged on. Charlotte Mandel, “Letters Across the Atlantic: H.D., Bryher, May Sarton, During World War II,” in A Celebration for May Sarton: Essays and Speeches from the National Conference “May Sarton at 80: A Celebration of Her Life and Work,” ed. Constance Hunting (Orono, ME: Puckerbrush Press, 1992), 98.

48. Quoted in Renata Morresi, “Two Examples of Women’s ‘Hidden’ Cultural Net(work): Nancy Cunard’s Onion and Life and Letters To-Day,” in Networking Women: Subjects, Places, Links Europe-America: Towards a Re-writing of Cultural History, 1890–1939, ed. Marina Camboni (Rome, Italy: Edizioni di Storia e Litteratura, 2004), 376.

49. Morresi, “Two Examples,” 376.

51. Interestingly, Rachel Blau DuPlessis and Susan Stanford Friedman recount one episode in which Bryher was kept from publishing a poem by H.D. (“The Master”), which the poet denied her the rights to. For a fuller discussion, see “‘Woman is Perfect’: H.D.’s Debate with Freud,” Feminist Studies 7, no. 3 (Autumn 1981), 417–430.

52. Hamish Miles, “Contents,” Life and Letters 12, no. 64 (April 1935): fp.

53. Bryher, “Contents,” Life and Letters To-Day 13, no. 1 (September 1935): fp.

54. Morresi, “Two Examples,” 375.

55. Mandel, “Letters Across the Atlantic,” 98.

56. “Editorial,” Life and Letters To-Day 13, no. 1 (September 1935): 2.

57. Bryher, The Heart to Artemis, 181.

58. Bryher, The Days of Mars. A Memoir. 1940–46 (London: Calder and Boyars Ltd., 1972), 33.

59. Kusch, “Not a Continent I Dreamed About,” 2.

61. From 1920 until 1950, Bryher’s travels and residences span the globe: New York, California, Paris, London, Cornwall, Berlin, Switzerland, Greece, Egypt — to say nothing of a childhood spent partly in Morocco and Saudi Arabia.

62. Bryher, “Paris 1900,” Life and Letters To-Day 16, no. 8 (Summer 1937): 33.

63. Bryher, “Editorial,” Life and Letters To-Day 15, no. 5 (Autumn 1936): 2.

65. Bryher’s suspicion of state-sponsored censorship can be traced at least as far back as her work for Close Up and her 1927 book-length study, Film Problems of Soviet Russia (Bryher, “Editorial,” Life and Letters To-Day 15, no. 5 [Autumn 1936]: 3).

66. Bryher, The Heart to Artemis, 326.

67. Bryher, “Editorial,” Life and Letters To-Day and The London Mercury and Bookman 64, no. 1 (January–March 1950), bound (London: The Brendin Publishing Company, Ltd.), 172.