Several kinds of chronicler, he's been

The books and selves of Lawrence Joseph

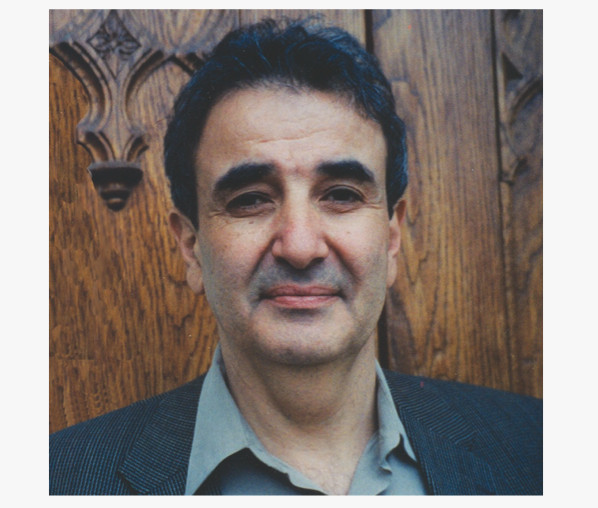

Critics often introduce Lawrence Joseph through his biography. David Kirby’s 2005 review of Codes and Into It for the New York Times, for example, musters geography, ethnicity, religion, and the law to make the poet seem at once exotic and familiar.[1] First we meet Joseph the lawyer-poet: a hybrid guaranteed, even now, to catch the reader’s eye. (Twenty years ago David Lehman introduced Joseph to Newsweek readers in just the same way: “Do poetry and the law make strange bedfellows? Lawrence Joseph thinks not.”)[2] Next, in a flashback paragraph, we learn that the poet “was born in Detroit in 1948, the grandchild of Lebanese and Syrian Catholics” and that his poems “speak of his family’s often trying experiences: the slights […] and the violence, especially the 1967 riot that left sections of downtown gutted and the wounding of his father, a grocer, in a 1970 holdup attempt.” After this appeal to pathos Kirby sketches Joseph’s literary career in chatty, even chummy language. “Not surprisingly, Joseph’s earlier writings include a lot of who-am-I poems,” the critic begins; over time, those evolve into the world-weary observations of an urbane attorney. “[A]s Joseph the lawyer makes his way up the ladder,” we learn, “Joseph the poet begins to use phrases like ‘financial markets’ and ‘decreased foreign investment’” and “the voice in the poems expresses malaise: ‘I make favors, complain, wear / a white shirt and blue suit. I’m tired.’”

But to introduce Joseph as “[t]he Catholic, Lebanese son of a Depression-era auto worker in Detroit,” as Michael True calls him in Commonweal,[3] or as a grandson of immigrants who “himself worked in the auto plants,” as David Wojahn ups the ante in Writer’s Chronicle,[4] is not simply to wrap him in the familiar contexts of ethnic identity and working-class authenticity. Nor, pace Kirby, need it merely inscribe him in a twice-told tale of social mobility and its discontents. This sort of introduction can also place him in a literary context. “It is not surprising, given his background, that his early work is considerably influenced by Philip Levine” Wojahn thus tells his readers;[5] “[l]ike Philip Levine, that other Detroit poet,” writes Paul Mariani in America, Joseph begins by invoking urban particulars: “the 7-Up Cadillac Bar, Our Lady of Redemption Melchite Catholic Church, Seminole and Charlevoix and Mack Avenues,” and so on.[6] As Joseph leaves behind this “skillfully rendered but familiar sort of personal lyric”[7] for a more jagged, elusive, collagist poetics marked by “jump-cuts” and a “lashing together of lyric reflection with snippets of testimony,”[8] he does so as part of a broader, decade-defining turn in American verse. “The sensibility at work in Joseph’s poems,” Roger Gilbert explains in his review of Before Our Eyes, “is that of a troubled aesthete, a connoisseur of light and color who keeps reminding himself that people are dying in the streets. The note has become a familiar one in recent poetry.”[9] On this account, Joseph evolves from a patently autobiographical ethnic and regional poet such as Levine into a poet of “textured information” more readily comparable to Robert Hass, Jorie Graham, and Ann Lauterbach — all poets who write in the “disjunctive, contrapuntal, nervously skittering” poetry that Gilbert identifies as the “period style” of the 1980s.[10]

This contextual narrative places Joseph both in time and in space. It makes the transition in his work correspond, more or less, to his relocation from Detroit to New York City; it lets him stand as a chronicler not only of the social reality that has surrounded him, but also of the changes in literary fashion. Nowhere in this story, however, do we hear about the ways that Joseph’s early work already stands back from the 1970s “personal lyric,” whether by embedding poems from this mode into mythic, high-modernist contexts, or (a volume later) questioning both the personal lyric as genre and the vision of selfhood it depends upon. Neither do we learn from it how his more recent books return to and revitalize that early religious, even visionary mode, bringing glimpses of unexpected depth beneath (or above, or within) the jostling surfaces common in poetry of “textured information.” The reductive smoothness of this contextual introduction, that is to say, needs to be ruffled by a counternarrative, one that accounts for the complexities within each volume, and also for the dramas of departure and return that constitute Joseph’s “breaking of style” from poem to poem, book to book, and literary self to literary self.[11]

Tracing this counternarrative, we discover a poet who is a far less autobiographical, far more consciously fictive character than critics have described. Perhaps we should have expected this. “The ‘I’ in the poems,” Joseph has insisted, “is Rimbaud’s modernist ‘The I is another.’”[12] But this spare, allusive proviso does not prepare us for the artful distance the poet maintains from the selves that he variously mythologizes and debunks, brings into focus and plucks from our grasp, in each new collection. The unit of composition for Joseph proves to be as much the book as it is the standalone lyric. Each collection revolves around a different central concern; or, rather, given the dialectical nature of Joseph’s imagination, each mulls over or works through its own distinctive set of “refractory contraries,” generally signaled by the opening gestures of each volume.[13] To appreciate the poems in any given book, you need to read them in light of their titles, epigraphs, or opening poems, with those contraries at stake. To give each successive volume its due, you need to see how it introduces the poet freshly to his readers, not least by repeating and varying each introduction that has come before. In this essay, I will trace these selves and self-introductions in Joseph’s first three books, which function as a sort of triptych. The self we see at the close of Before Our Eyes is, to my mind, essentially the same as the one we encounter a dozen years later in Into It, however violently the world surrounding that self has changed.

“I was appointed the poet of heaven”: Shouting at No One

Clues to this contrapuntal story can be found in the few poetics statements and interviews that Joseph has used to contextualize his work. Compared to his contemporaries — Heather McHugh, for example, or Barrett Watten, both born, like Joseph, in 1948 — he has offered few such documents; given this scarcity, the consistency of the few we have takes on particular significance. In them, Joseph has doggedly insisted that his work be read in the contexts of international modernism, not just recent American literature. When interviewer Charles Graeber remarks that Joseph’s early poetry “reminds me topically of Philip Levine’s Detroit poems,” for example, the poet patiently counters that those pieces lie, instead, “in the tradition of post-Baudelairian ‘city’ poetry,” so that “ Detroit’ is, in the book, essentially metaphorical — an emblem, or code.” “I consider myself in the tradition of American poets who have written not only out of the American tradition, but out of traditions other than our own,” Joseph told the Poetry Society of America in 1998.[14] When Contemporary Authors invited him to describe his poetry to the students who consult this reference resource, Joseph explained that he dreams of “embodying a cosmopolitanism.”[15] The gathering of apothegms, observations, and epigrams he calls “Notions of Poetry and Narration” features more than a dozen European and Levantine authors, from Apollinaire, Brecht, Cavafy, and Dante to Ferdinand Pessoa and Christa Wolf. One figure in particular, the Italian modernist Eugenio Montale, gets quoted or cited fourteen times, making him a presence second only to Wallace Stevens in this crucial collagetext. (There is no sign at all of Philip Levine, Robert Hass, Jorie Graham, or Ann Lauterbach.)

Among the Montalean sources Joseph quotes is the germinal essay “Reading Montale” by the poet, translator, and editor Jonathan Galassi.[16] The essay proves a useful guide to the untitled, italicized poem that opens Joseph’s first book, Shouting at No One: a poem, that is, whose typography and prefatory setting echo the famous untitled, italicized poem at the start of the Italian poet’s first collection, Ossi di seppia (Cuttlefish Bones).[17] According to Galassi, this Montale poem, commonly known as “At the Threshold,” introduces us to the enduring narrator of the author’s major poetry, “melancholy, solitary,” an “old young man” whose relationships with history and other characters, both human and semidivine, the rest of the work will trace. It places this man in a resonant, shifting landscape, a coastal orchard, which will serve as the point of comparison for the poems’ later settings. (They grow more urban, or return to rural life; they invoke the sea or rivers or gardens, or again leave these behind.) Finally, the prefatory poem introduces us to the speaker’s core anxiety — a radical solitude that leaves him “extraneous to life,” buffeted by the indifference of history — and also to his characteristic turn to “a saving other,” a you whom he can address, and who can in turn “recognize him and thus rescue him from the prison of himself.”[18]

Does any of this material — either Montale’s method or his underlying narrative — inform Shouting at No One? Here, too, a prefatory poem introduces us to the poet’s unnamed “I,” not in the paradisal “enclosed garden” of the Italian poem, but in heaven itself. “I was appointed the poet of heaven,” the text begins; “It was my duty to describe / Theresa’s small roses / as they bent in the wind” (3). The duty of beauty, we might call this, an aesthetic version of the submission to Spirit taught by Saint Therese, the Carmelite “little flower of Jesus.” Appropriately, Joseph’s verse aspires here to a mimetic free verse prosody, shifting in the second three-line stanza from a casually iambic tetrameter (“it was / my du / ty to / describe”) to a pivoting trochee that snaps the first image into focus (“There / sa’s small / roses”), only to resolve in a graceful, windbent pair of anapests (“as they bent / in the wind”). “A technique sheared of traditional poetic values,” Richard Tillinghast fretted in his otherwise positive review of Shouting at No One, but these lines suggest that those traditional values are quite consciously on display as the volume begins.[19]

Having given us a whisper of paradise — and, in the process, of the limited, purely mimetic function of the poet to be found there — the poem takes its first turn. “I tired of this,” Joseph’s narrator shrugs, “and asked you to let me / write about something else.” The verb “write about” is only slightly more active than “describe,” but the torque of the enjambment before it, the liveliest so far, draws our attention to the change. So does the response that Joseph’s speaker receives to his request. Peremptory, Joseph’s first “You” calls the poet of heaven back to his original duty:

You ordered, “Sit

in the trees where the angels sleep

and copy their breaths

in verse.”

So I did,

and soon I had a public following:

Saint Agnes with red cheeks,

Saint Dorothy with a moon between her fingers

and the Hosts of Heaven.

Either God or a muse — and the difference means little, at this point — the “you” of the poem orders the poet to “sit […] and copy,” again with his attention focused on something spiritual, at least in the etymological sense. (If “wind” bent Theresa’s roses, now the poet must copy “breaths.”) Although the poet says that he complied, the lines that follow suggest otherwise. His lines grow expansive: first a proud pentameter boast (“and soon / I had / a pub / lic fol / lowing”) that lets human literary tradition, and not angelic breath, determine his cadence, and then, as the saints arrive, a pair of descriptions that refuse to echo traditional iconography. Saint Agnes is blushing, and missing her lamb; Saint Dorothy has traded her flowers and basket for a “moon” that resembles, by proximity to “host,” a communion wafer.

Inventive, disobedient, and idiosyncratic, the “poet of heaven” has built an audience for himself. The dimeter line that ends this stanza — “and the Hosts of Heaven” — lingers in self-satisfaction, echoing and answering the first markedly alliterative line, “[i]t was my duty to describe.” Provoked, the “you” abruptly intervenes:

You said, “You’ve failed me.”

I told you, “I’ll write lovelier poems,”

but you answered,

“You’ve already had your chance:

you will be pulled from a womb

into a city.”

To the “You,” loveliness inheres in the subjects of the poems, which their texts simply mirror. That the poet returns to his own verb, “write,” and aspires to write “lovelier poems” rather than humbler, more accurate ones, already marks his fall. With a Dantean sense of appropriate punishment, the “You” dooms the “poet of heaven” to a realm where any loveliness will have to come from his own efforts, one marked not only by the sexuality and violence absent from his native realm, but also by the variety and specificity he seems to crave. “[P]ulled from a womb / into a city,” the poet will have to discover, or invent, what the duty of an urban poet will be.

Set at the threshold of Shouting at No One, this prefatory poem informs the rest of the text in ways that have not, I think, been sufficiently recognized. When the second poem of Shouting at No One plunges us immediately into a painful earthly narrative — “Joseph Joseph breathed slower / as if that would stop / the pain splitting his heart,” it begins — we are meant to notice not only the contrast between the world this poem describes and the one we saw a few pages before, but also the bittersweet turn in the literary activity of the exiled “poet of heaven” (7). Once ordered to copy the breaths of angels, he now records the breaths of a man in pain, both through narrative and, again, through artful, mimetic rhythm. Once eager for “something else” to write about, his lines now spill over, sharply enjambed, from narrative into an angry, expansive catalogue:

He turned the ignition key

to start the motor and leave

Joseph’s Food Market to those

who wanted what was left.

Take the canned peaches,

take the greens, the turnips,

drink the damn whiskey

spilled on the floor,

he might have said. (7)

At which moment, if we are paying attention, we realize that this apparently obedient and mimetic poetry has shaded, quietly, into an act of imagination, a thought of what “he might have said.” The poem returns to simple narration, as though its speaker were trying to force himself simply to say what happened, but most of the events he now describes are mental, lit by glimpses of a world elsewhere:

Though fire was eating half

Detroit, Joseph could only think

of how his father,

with his bad legs, used to hunch

over the cutting board

alone in light particled

with sawdust behind

the meat counter, and he began

to cry.

This lovely image — the grandfather backlit, almost haloed, like St. Joseph, as light catches sawdust “behind / the meat counter” — is particularly poignant if we come to it, as the “poet of heaven” would, with the static, idealized female saints of the previous poem in mind. It stands poised between two versions of poesis the exiled poet continues to negotiate, one mimetic, descriptive, obedient to its subject, the other more independent, idiosyncratic, restless in its search for new material.

The prefatory poem also gives us a second opposition: “heaven” versus the “city.” Given Joseph’s claim, in the Graeber interview, to be writing “in the tradition of post-Baudelairian ‘city’ poetry,” it is safe to say that this last is his version of the competing attractions of ideal beauty and urban abjection, salvation and the sordid, that characterize this tradition from Baudelaire to Eliot to Ginsberg.[20] As Michael Hamburger explains in The Truth of Poetry, a study which Joseph cites a half dozen times in “Notions of Poetry and Narration,” this sort of “a polarity that corresponds to Baudelaire’s spleen and ideal’” rarely lets the poet take one side or the other.[21] Rather, they function dialectically, so that even the poet who aspires to write one sort of verse — a “low mimetic” antipoetry or an “autotelic or hermetic art” of pure imagination — will find him- or herself driven to give voice to the other.[22] Hamburger describes the former, low mimetic verse as “austerely dedicated to rendering ‘things as they are’ in the language of people as they speak,”[23] but in an inventive twist on this familiar topos, Joseph begins Shouting at No One with a “poet of heaven” for whom “things as they are” would be idealized, celestial, and delicate, so that his original acts of imagination drive him initially down the ladder of mimesis. The next poem, “Then,” inverts this progress, as the exiled “poet of the city” tries, however briefly, to imagine an alternative to the low mimetic world that traps his father, his grandfather, and perhaps himself.

The final sentences of “Then” offer additional glimpses of heaven, or the ideal, reduced or recast as low mimetic detail. The “old Market’s wooden walls / turned to ash” (7) recall the earlier “trees where the angels sleep” (3), here cut down and burned; the “tenement named ‘Barbara’ in flames” (7) recalls another female saint, or ought to have done so. Like the spiritual “fancies that are curled / [a]round these images, and cling” in Eliot’s “Preludes,” echoes of heaven and sacred history inflect the poem’s arson-ruined streetscape.[24]

Indeed, in light of the prefatory poem, we can see this doubleness throughout the volume. The urban details that establish, for Graeber, a “sense of place” also establish a profound sense of displacement, since every geographical specific (Van Dyke Avenue, the 7-Up Cadillac Bar, the Eldon Axle factory) recalls the lack of such spatial markers in the heaven where we began, just as every house of worship (Mount Zion Temple, St. Marion’s Cathedral, Our Lady of Redemption) reminds us of the speaker’s exile.[25] This doubleness is perhaps most plangently deployed in “Do What You Can,” a poem that opens with one of those emblematic houses of worship (“the Church of I AM”) and ends with a striking deployment of legal discourse. “I wonder if they know,” Joseph writes in the closing lines,

that after the jury is instructed

on the Burden of Persuasion and the Burden of Truth,

that after the sentence of twenty to thirty years comes down,

when the accused begs, “Lord, I can’t do that kind of time,”

the judge, looking down, will smile and say,

“Then do what you can.” (58)

We do not need the prefatory poem to make these details resonant, but it makes their overtones inescapable. The poet knows these things because he, too, operates under twinborn burdens of rhetorical invention (Persuasion) and mimesis (Truth); he, too, has been sentenced, doomed to a life of (in Montale’s words) “total disharmony with the reality that surround[s]” him.[26] The effect is not to tug our attention away from the purely human legal drama of the poem’s close, but rather to magnify and dignify it — and, in the process, to bring others into the ennobling penumbra of the poet’s otherwise private myth. Both the poet and those he observes live, here, under the same cool condemnation, with “Do What You Can,” a fallen city’s muted golden rule.

“I distance myself to see myself”: Curriculum Vitae

Can we tease out a single, coherent myth of the poet from Shouting at No One? Joseph changes his story as the book goes on, so that the voice of poetry “howling within” him is ascribed first to himself (“Then,” 7), then to an angel (“Not Yet,” 21), and in the volume’s closing lines to God himself. Given time, one might sort these out into a single narrative, perhaps even the sort of novelistic “plot” that Galassi’s “Reading Montale” traces through that poet’s work. For the purposes of this essay, however, it suffices to say that the aspiration to myth announced in the prefatory poem lifts its subsequent texts out of the realm of personal lyric, locating them in an ambiguous generic realm somewhere between Montale’s symbolist modernism and the postconfessional lyric of the 1970s. Asking not “who am I,” but “what voice is it in me,” this volume uses the contraries implied by its prefatory poem to add complexity and power to the rest of the book. Backlit by the heavenly scene of the first poem, the urban memories of “Then” and the empathic, humbly observed “Do What You Can” read differently than they do when read on their own; in a longer essay, I would explore how the prefatory poem ballasts the self-celebratory claims of “There Is a God Who Hates Us So Much” (“I was pulled from the womb / into this city” [46], it begins) and how the portrait-poems that flesh out the collection, especially those about immigrants to Detroit, play out on a horizontal axis the same displacements we see in the poet-of-heaven’s vertical exile.For now, let me simply recall Hayden Carruth’s wise dictum that “[b]efore a person can create a poem, he or she must create a poet.”[27] Shouting at No One is as much about that “primal creative act” as it is about Detroit or the poet’s life there per se.

Published five years later, Joseph’s second collection, Curriculum Vitae, sets aside both the vertical axis of Shouting at No One (heaven to the city) and the grand, even mythic approach to the poet’s voice that the first book employed. This is not to say that it abandons them entirely. Read the collections back to back, as they appear in Codes, Precepts, Biases, and Taboos, and you see immediately how Joseph marks each turn in his work through repetition and variation. “It’s not me shouting at no one / in Cadillac Square: it’s God, / roaring inside me, afraid / to be alone,” the first book ends (60); “The disabled garment worker / who explains to his daughter / he’s God the Holy Spirit / and lonely and doesn’t care / if he lives or dies” (65), the next begins, collapsing myth into mental illness, prophetic roaring into explanation, sternness into — well, not sympathy, but something watchful, a little detached, but curious, willing to learn. The speaker, we might say, takes note of these characters, father and daughter, before turning (as the sentence spills forward) to other topics that catch his eye or demand his attention. Framing its introduction of the poet in the educational and professional terms suggested by its title, Curriculum Vitae stays — for the most part — resolutely secular; where religion appears, it is primarily as part of the speaker’s upbringing or an instance of culture. (I will discuss one crucial exception, “Let Us Pray,” later in this piece.)

If any collection invites us to read Joseph as a poet of ethnic, even racial heritage and social class, it is Curriculum Vitae. The title poem (69–70), early in the collection, touches on Arab American identity (“I might have been born in Beruit, / not Detroit, with my right name,” it begins), and in a half dozen lines it runs through this book’s secular versions of the poet’s recurrent motifs: urban violence (“fire in the streets”), the liberating power of the imagination (“My head set on fire in Cambridge, / England, in the Whim Café”), the impact of legal training on the poet’s mind (“After I applied Substance and Procedure / and Statements of Facts / my head was heavy, was earth”). The collection includes a set of poems about autoworker life and the shady wealth that surrounds it; here, too, we find “Sand Nigger” (90), a meditation on Lebanese-American identity that, writes Lisa Suhair Majaj, “Arab-Americans frequently invest with iconic status.”[28] Certainly it remains one of Joseph’s best-known, most-anthologized pieces, and it earns that reputation not least in its bravura closing lines, where the speaker claims and inhabits the insulting name he has been called outside the shelter of home. “‘Sand nigger,’ I’m called, / and the name fits,” he says with a touch of swagger, embracing the clarity of identity that opposition provides. The poem’s final cadence nests a memorable series of oppositions: the poet may be “nice enough / to pass,” but he is also “Lebanese enough / to be against his brother, / with his brother against his cousin, / with cousin and brother / against the stranger” (90, 92).

As was the case with Shouting at No One, however, these poems of identity read differently when we set them in the context of the volume as a whole. Here, too, Joseph frames them, gives them additional complexity, through a series of self-introductory gestures, beginning with the poem’s epigraph. “Both in nature and in metaphor,” he quotes Wallace Stevens, “identity is the vanishing-point of resemblance” (63). To a poet, this adage suggests, identity will always be a troubling ideal. Resemblance proliferates, is itself creative, the spark of simile and metaphor. (“It is only au pays de la métaphore / Qu’on est poète,” Stevens reminds us elsewhere.)[29] Identity, by contrast, marks the end to the perception of sameness in difference, difference in sameness, that is so crucial to poetic creation. When two things are identical, after all, they no longer resemble one another, they simply are one another, tout court. This is not to say, however, that identity has no use, no appeal. Identity, writes Stevens, is a “vanishing-point”: in visual terms, this would be the place where parallel lines converge. In representational art, this illusory point of convergence helps establish our sense of perspective. Although in real life it vanishes as we approach it, in art the vanishing point grants depth and heft to everything around it. By implication, then, identity is the place where otherwise parallel lines of life can finally meet: an ever-retreating, fictive construct, but one which brings both resemblances and differences into some harmonious array. Without such a vanishing point, the self might fracture along cubist, multiperspectival lines or dissolve into a swarm of resemblances; at identity’s purest extremes, however, as resemblance vanishes, identity too disappears, a victim of its own self-congruity.

Joseph begins to explore the implications of his epigraph in the poem that opens Curriculum Vitae, “In the Age of Postcapitalism.” It begins with a paratactic array of characters and images, as though challenging the reader to spot the resemblances between them:

The disabled garment worker

who explains to his daughter

he’s God the Holy Spirit

and lonely and doesn’t care

if he lives or dies;

the secret sarcoma shaped like a flower

in the bowels of a pregnant woman;

ashes in the river, a floating chair,

long, white, shrieking cats;

the watch that tells Zurich,

Jerusalem, and Peking time;

and the commodities broker

nervously smiling, mouth slightly twitching

when he says to the police he’s forgotten

where he left his Mercedes:

everything attaches itself to me today. (65)

In the previous volume, each of these figures would have been plotted on the clear, definitive axes that ran vertically from heaven to the city, and horizontally, from Lebanon or Armenia to Detroit. Here pathos, disease, urban decay, cosmopolitan elegance, and a lying businessman simply heap up, defying our efforts to read them as instances of some common plight. To use the metaphor implied by the book’s epigraph, they are parallel lines in search of a vanishing point. As the sentence ends, they find one. “Everything,” we read after that colon, “attaches itself to me today.”

The first self we meet in Curriculum Vitae, then, is neither the wistful “poet of heaven” that started the previous volume, nor the empathetic observer of “Do What You Can” and the portrait poems, nor the fleshly, God-haunted, grimly exultant “poet of my city” we saw at its close. At the simplest grammatical level, he is a “me,” while the previous poet introduced himself as a subject (“I was appointed the poet of heaven”), often speaking a string of significant verbs: “I see,” “I answer,” “I press,” “I wonder” (“Do What You Can,” 57–58). It takes two more sentences for an “I” to enter the poem, and even then it is merely part of a quoted title, “What Has Become of / the Question of ‘I,’” one of several “topics for discussion / at the Institute for Political Economy.” Only after this title, as though in reaction to it, does the poet step forward as an “I” in his own right, learned in occult, Yeatsian lore, in the classical tumults of Eros and Eris (beloved of Sappho and H.D.), and in the mix of rhetorical craft and emotional self-knowledge that makes for literary art. Indeed, he is not just a poet — he is a poet with a beloved, a “her,” however incongruous his

longing may seem, given the times:

I know all about the transmigration of souls.

I know about love and about strife.

To delight in a measured phrase,

to bank the rage in the gut,

to speak more softly,

to waken at three in the morning to think only of her

— in the age of postcapitalism. (65)

It’s as though the speaker heard his own tone soften and recoiled, taking refuge in irony, a knowing shrug, a crisp, theoretical phrase he might have heard at the Institute of Political Economy mentioned a few lines above.

After twenty years of reading this poem, I still often stumble at this turn. The poem so far could easily end here: after all, Joseph has reached the phrase that gives the poem its title, and even more than “everything attaches itself to me today,” this new line offers a briskly summative, clarifying, metatextual gesture. We can use it to name, even to diagnose the lack of “identity” we saw in the speaker during the first part of the poem, the gap between that meager self and the older set of values (religious, aesthetic, amatory) that the speaker goes on to invoke, and even the poem’s bracing turn to the discourse of critical theory, which snaps us out of our nostalgia for those values. All of these, we are invited to nod, characterize an “age of postcapitalism” and the poetry appropriate to it. In such poetry, words like “love,” “strife,” “delight,” and “waken” will mix promiscuously with the language of political economy; in it the longing for love will be at best a local nostalgic effect, a pleasure which the poet will not luxuriate in, but will instead unmask. The self this longing implies, with its old-fashioned inwardness, is a similar effect, likewise to be debunked. Abrupt and disruptive, the phrase “in the age of postcapitalism” draws our attention away from the referential side of the poem — the world it describes and the self who describes it — and sternly fixes our attention on the language of the poem itself.

Such disruptions were not hard to find in poetry of the late 1980s. Indeed, by 1988, when Curriculum Vitae was published, they were common enough in the work of Language writers to have drawn several years of mainstream critical attention. Joseph, however, refuses to end his poem here. If the line “in the age of postcapitalism” steps back from and names the situation in which the poet finds himself, the fact that the poem continues, shifting gears once more, suggests that Joseph also steps back from the theoretical discourse in which terms like “postcapitalism” allow intellectual mastery and oppositional authority. In a deliberately anticlimactic gesture, the poet sets that discourse, too, aside, and looks outward:

Yellow and gray dusk thickens around the Bridge.

Rain begins to slant between

the chimneys and the power plant.

I don’t feel like changing

or waiting anymore either,

and I don’t believe we’re dreaming

this October sixth, in New York City,

during the nineteen eighties. (66)

In Shouting at No One, rain like this would have signaled a gust of redemption, or at least a reminder of its enduring possibility. (“I’ve always waited: / for warm rain to wash the sky,” Joseph writes in this vein in the earlier poem, “Nothing and No One and Nowhere to Go,” 41.) Here, though, it has no such effect; in fact, the poet specifically rejects that hope of change. Neither as scattered as the earlier “me” nor as confident as the subsequent “I,” the speaker rallies himself as best he can in a collective pronoun, but he does so quietly, even sadly, as though both he and the rest of that “we” were simply the victims of time and place without any power to resist, define, or affect them. Even the term “postcapitalism” loses its critical force by the end of the poem, becoming simply part of the linguistic fabric of New York City in the 1980s. In effect, the poem historicizes the term, but the move is less scholarly than simply middle-aged, as though its speaker had already seen too many such phrases go in and out of intellectual fashion.

The first self that we meet in Curriculum Vitae, then, is constituted by the parallel lines of information that “attach” themselves to it, by parallel lines of discourse — poetic and political — and finally by the time and place in which this self-by-accrual occurs. It’s a self that is by turns interested, overwhelmed, assertive, nostalgic, ironic, and melancholy, but one without a single, clearcut identity that would bring these materials into balance and focus. In his sonnet “Meru” Yeats speaks of the way thought goes on “ravening, raging, and uprooting” until one comes to “the desolation of reality.”[30] In a quieter way, this speaker has arrived at a comparable desolation, as though he were simply too knowing for his own good, his intelligence and his sense of identity somehow at odds. To buttress that sense of identity, the poet of this volume needs either to find a self that will withstand the ravening appetite of thought or to construct one, consciously, as the sort of vanishing point in which these parallel lines can meet. And, indeed, the rest of Curriculum Vitae pursues this twofold project of self-discovery and (or through) self-invention, with the book more or less alternating between poems that look into the past for the roots of the present self and poems that step back to challenge, complicate, and even “uproot,” as Yeats says, what was planted a page before. Or, if you prefer, about half pursue the disjunctive, cubist poetics of “In the Age of Postcapitalism,” while the other half step back from that period style to challenge and complicate it. In these, the impulse to see the world in this depthless way rises from the depths of the poet’s identity:

“This is a smart one,” Mama says.

My eyes are as black as hers.

“Too smart, I’m afraid — he’ll

keep unhappy because of it,”

Mama said. I heard her.

That’s what Mama said.

On the feast of my patron saint

that’s what my mama said. (67–68)

Thus the end of the volume’s second poem, “My Eyes Are as Black as Hers,” a poem which had been, until these lines, entirely in the third person. Being “too smart” is not just the cross this “I” has to bear, this grammatical turn suggests. Rather, it is the core fact that makes him an “I” in the first place, one that will keep him, for the rest of his life, from comfortably, unquestioningly inhabiting any single identity. (The authoritative trimeter of the final stanza, less flexible than the looser quatrains before it, reinforces our sense that this is a clinching, definitive moment.)

Of the twenty-six poems in Curriculum Vitae, a dozen, by my count, look back to the disjunctive lead of “In the Age of Postcapitalism.” In these, the reader is often given what we might call “parallel lines” of material, arrays of fact, memory, and observation that seem, at first, “impossible together” (“By the Way,” 81); often the self that speaks them is distanced into the second or third person, haunted by his own self-consciousness. “Myself — an abstraction” he’ll call himself in such self-critical moods, or dismiss himself as an aesthete past his time: “‘Live and die before a mirror,’ / Baudelaire says, sipping espresso / at the corner of Hudson and Barrow” (“I Pay the Price,” 105, 107). But this unrelenting intelligence has an ethical side that cannot be dismissed. Turn the page on “Sand Nigger” and you’ll find “Rubiyat,” a poem whose fourteen jagged quatrains of “how the brain talks, evil in its wakefulness” pepper the reader with clipped, disconcerting sentences. The identity-through-opposition offered by the first sounds good on paper, the gesture suggests, but in historical practice, it is a bewildering nightmare, “too crazy and it’s too much and not unreal” (93). “[W]hat do you think you’re doing,” the speaker of this poem demands of himself, “when you want the names / and the years of the history, who begot whom and who made / which flesh which words that hate for which particular reasons / that compel the pride of the horrors of the oppressed?” Yet ask he must, want he must: the intellect, too, has an appetite, which battens equally on beauty and on atrocity. In the remarkable poem “An Awful Lot Was Happening,” which speaks of war, religion, urban strife, and romantic love during the Vietnam War, Joseph gives us that appetite voice — in fact, in a rare move for the volume, he grounds it in a confident, crisply defined identity. The final three stanzas are worth quoting at length, to see what this self looks like:

When I answered I intended to maintain freedom my brother was riled.

What, or who, collides in you beside whose body I sleep?

No work at Tool & Die, Motors, Transmission, or Tractor

while the price of American crude rises another dollar.

There really wasn’t enough work anywhere. And there was war

God the spirit of holy tongues couldn’t release me from,

or from my dumbness. Pressured — delirious —

from too much inductive thinking, I waited for

the image in whose presence the heart opens and opens

and lived to sleep well; of necessity assessed earth’s profit

in green and red May twilight. —You came toward me

in your black skirt, white blouse rolled at the sleeves.

Anticipation of your eyes, your loose hair!

My elementary needs — to cohere, to control.

An awful lot was happening and I wanted more. (103–04)

As a poem of education — sensual and otherwise — this piece can contain both disjunctive turns and memory-based lyrical passages in a poised, harmonious balance. Few poems in the book present the poet’s “I” as at once this confident and this expansive; as much as “Sand Nigger,” it is a touchstone in the collection.

I have discussed Curriculum Vitae so far in the terms suggested by its epigraph — resemblance, identity, and the complex figure of the “vanishing-point.” The reference to “political economy” in this book’s opening poem suggests another, equally powerful lens through which to view the collection. Joseph wrote these poems at a time when many voices debated the relationships between postmodern poetry and contemporary economics. Frederick Jameson’s germinal essay “Postmodernism, Or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism,” for example, came out in the New Left Review in 1984, and was contested and echoed by poets and critics, especially those interested in Language writing, well past the end of the decade.[31] As we have already seen, Joseph keeps his distance from the term “postcapitalism,” but simply by using it in the opening poem, he primes us to notice how often the poems that follow speak not just of money, but of a self that sees itself in economic terms. The young man who stuffs a ten-dollar bill in his pocket, earned through work as a caddy, contrasts his well-earned payment with the “wonder” of money made by “‘Dice’ Delaney,” the golfer who hires him, through bets. “I knew where it came from. / I knew this much was mine,” he says (“This Much Was Mine,” 79–80). Older, a poet, he sometimes seems to doubt the value of his imaginative work. “I frequent the Café Dante, earn / my memories, repay my moods,” he insists, a bit defensively, near the close of the title poem, adding, “I am as good as the unemployed / who wait in long lines for money” (“Curriculum Vitae,” 69, 70). In his own “lines,” filled with memories and moods, the poet seems to covet the same moral stature.

The final poem in Curriculum Vitae, “There I Am Again,” reminds us why Joseph finds capitalism and identity so deeply intertwined. Where the volume began “in New York City, / during the nineteen-eighties” (“In the Age of Postcapitalism,” 66), it ends by taking the poet back to the family market that we saw destroyed near the start of Shouting at No One. This time, however, the core of the memory is not the store’s destruction, nor the work of the poet’s father and grandfather, but the poet’s youth working behind the counter. “[T]here I am again: always, everywhere,” Joseph writes in the book’s final lines, “apron on, alone behind the cash register, the grocer’s son / angry, ashamed, and proud as the poor with whom he deals” (121). As we have seen, this is not the only self that the speaker contains; the “smart one” recognized by his mother is an even older, equally enduring identity, and one that Joseph has deployed to take a second, critical look at his own gift for identity poetics. At the end of the collection, Joseph reverses this gesture. The “grocer’s son” self tethers and grounds the skittery, unrelenting movement of his intellect, on fine display in the penultimate poem, “On Nature” (118). And because it embraces the risk and shame of an old-fashioned, pre-postcapitalist economic position, “alone behind the cash register,” forced to “deal” directly with others, this self also sponsors the poet’s sense of values, of human worth.

“Vision sustains”: Before Our Eyes

The title of Joseph’s first book, Shouting at No One, hinted at mysteries. A participial phrase, it signaled that the book would explore an activity (poesis, or some variant of it), and that this activity would be done at no one by someone yet to be named (the poet of heaven, or a voice within, or God, depending on the poem). Curriculum Vitae presented us with a crisp, professional term: an abstract, impersonal noun-phrase, “the course of a life,” which the book by turns fleshed out and reflected upon, its poems as often meditations on identity poetics as instances of them. As a title, Before Our Eyes speaks in the first person plural, a new grammatical choice that suggests Joseph has moved beyond the inquiries into self that shaped the first two books. “Myself, / self-made, separated from myself, // who cares?” he shrugs in “Material Facts,” as though refusing to return to those earlier self-creative efforts (128). The plural possessive also tells us that the self we are about to encounter speaks on our behalf, or at least has settled more comfortably into his own multiplicity. Several pieces in the collection, notably “Generation” (138) and “Under a Spell” (135), even suggest that the other self within that “us” is the Muse, the “you — with whom I can’t pretend” who “see[s] everything go through me” (136).

The title phrase also suggests that this will be a book of imagistic or panoramic vision. The poet, one assumes, will describe what lies “before our eyes” in a spatial sense of the phrase, as in the opening lines of the title poem, which Joseph places, for the first time, first in the collection:

The sky almost transparent, saturated

manganese blue. Windy and cold.

A yellow line beside a black line,

the chimney on the roof a yellow line

behind the mountain ash on Horatio.

A circular cut of pink flesh hanging

in the shop. Fish, flattened, copper,

heads chopped off. (“Before Our Eyes,” 125)

Startling in their painterly palate, these descriptions strip the depth and pathos from material that, in an earlier book, would have been redolent with meaning. The shop, the flesh, the fish: we saw each in the final poem of Curriculum Vitae, but their roles as setting for a “grocer’s son” self, proud and ashamed, have been set aside in favor of an exact, purely visual delectation. Is this, at that, the same shop? “Horatio” is an avenue in Detroit — but also a street in Manhattan. The poem’s refusal to specify signals its freedom, at least for now, from the metaphorical geographies that shape the first two books.

But Joseph does not limit himself to what is “before our eyes” in this simple, visual sense. “The point is to bring / depths to the surface,” the poem continues, “to elevate / sensuous experience into speech / and the social contract.” The first of these admonitions goes down easily. Depths to the surface, experience into speech: these are unsurprising descriptions of poesis, although “elevate” is a verb we will return to. By adding “and the social contract,” however, Joseph reminds us that speech is not a neutral, private act. Because it implies an interlocutor, and because we must learn language from others, speech implies some kind of social order; it implicates us in one another in ways that poets both depend on and put to new use. A few lines later, Joseph puts these implications of poesis into practice. “By written I mean made,” he explains, “by made I mean felt; / concealed things, sweet sleep of colors.” The poem — a made thing, etymologically speaking — is “felt” by its author, bringing sensuous experience into language, but felt also by its reader, so that things once “concealed” can now be noticed or imagined, like a “sweet sleep of colors.” Such synesthesia and personification are not part of my perception of the world, or at least they were not before I read Joseph’s poem; now they are, which means that both my eye and my “I” have changed.

Language, we might therefore say, exists at once before our eyes and before our I’s, in both the spatial and the temporal senses of the phrase.[32] This spatial / temporal doubleness is, for me, the “refractory contrary” at the heart of Before Our Eyes — far more important a pair, in fact, than the tensions between “beauty and terror, lyric language and historical fact, aesthetics and politics” that Roger Gilbert has argued shape the volume.[33] In Gilbert’s reading, the title poem “traces the fluctuations of a mind in love with sensual beauty but oppressed by its knowledge of history,” and this “conflict of sensibility and conscience” leaves the poet trapped in the uneasy role of a “guilty hedonist.” This reading, however, reduces beauty to the merely visual, so that the tension in the poem lies between the “ephemeral impressions of colored light” and “social chaos” that both appear, spatially speaking, before the poet’s eyes.[34] For Joseph, however — a Catholic poet, steeped in Montale, Stevens, and Dante before them — earthly light and beauty have always at least potentially signaled something far greater, a spiritual radiance, a supernatural order in which beauty and morality, light and law and love, are not so easily distinguished. In this tradition, what comes “before our eyes” in the spatial sense is sometimes dramatically different from, even an affront to, what comes “before our eyes” in the temporal sense, although the two sometimes are interfused, when seen not just by sight, but through prophetic and / or sacramental vision.[35]

That Joseph might need to be read as a religious poet should not come as a surprise. The self in each of his books has been characterized in part — in no small part — by his relationship to the divine. In Shouting at No One the bond was close, but antagonistic. “Who makes me eat my words and makes my eyes pain: / I measure you according to your creation,” he cursed at the end of “There Is a God Who Hates Us So Much” (50). In Curriculum Vitae, the remarkable “Let Us Pray” offers a moment of direct address and connection. First the poet confesses (“I confess / too much”), then he begs to be “cleansed” like a prophet, his mouth made fit to praise (“Let me pray”). As the poem moves into the first person plural, the divine and human intersect: both “cry,” both have flesh and spirit — “Let us pray,” he now writes. In fact, by the end of the poem, it is God, not the poet, who needs consolation. “Let your cry come to me,” the poem ends, “I will not forsake you, / I, Lawrence Joseph, loved so much / by your pain and your beauty” (108).

In Before Our Eyes, Joseph finds a way to imbricate heavenly pathos and beauty with a deeply imperfect world of creation. “[R]efracted into depths // all beauty isn’t underlined,” he warns; sometimes it lies buried under “indignant and ironic // events blocked on top of one another,” so that it takes both grace and skill to spot it (“Now Evening Comes Fast from the Sea,” 175). But “[o]ut of deeper strata // illuminations” manage to rise, and they do so precisely as “confirmations of another order” (“Admissions Against Interest,” 132, 134). We find them in the sunlight that a child “catches / […] in a pocket mirror” and “refracts […] into a senator’s eyes” (“Generation,” 138–39); in the “darkening gold” underlying the disorderly social world (“Over Darkening Gold,” 137); in the “pure unattainable light” that family love recalls in “Sentimental Education” (146). Here and there illuminations erupt almost miraculously, as in “those fingers, / those beams of light / in the middle of the air” where — as the gospel song reminds us, Ezekiel saw the Wheel (“Time Will Tell If So,” 141), a figure that appears in its own right, “[o]ut of the [b]lue,” in the visionary poem of that name (“Out of the Blue,” 149). But their most vivid, unmistakable instantiation comes in a quotidian moment of grace captured in “Whose Performance Am I Watching?” as the poet catches a sacramental glimpse of a man and a woman:

“Just look!” and I did, and there, on the street, Hudson Street,

a rose-colored woman about to kiss a rose-colored man,

both of them older, under a linden tree, behind them

the elevated absence you’ve learned to let be. I’ve never

forgotten the expression on their faces, the only

human beings I’ve ever seen without that rapacious look

everyone else is possessed by. Brightness streaming in every

direction. Judgment, desire, sentence structure taking place.

Not in Siena, but right here. (144)

By linking the visual trope of “brightness” so memorably here with love and judgment, desire and language, Joseph invites us to read those qualities back into other mentions of light elsewhere in the collection, as well as later in this particular poem. (They are, I take it, all attributes of the “opulence” that sunlight “insinuate[es]” as this piece comes to a close [145].) Even the cover art of Before Our Eyes in its original publication underscored this connection. It presents an array of the famous bodiless angels painted on the ceiling of the church of Debre Berhan in Gondar, Ethiopia: a church whose name means, in Amharic, “Mountain of Divine [or Heavenly] Light.”

In the “sacramental” vision of the Catholic poet, Paul Mariani has written, “Evidence of God’s immanent presence ought to be capable of breaking in on us each day, the way air and light and sound do, if we only know what to look and listen for.”[36] Clearly Joseph offers such evidence elsewhere in Before Our Eyes, but does he introduce this motif — does he suggest we “look and listen” — in the collection’s opening poem? The answer comes, for me, in the suite of ars poetica statements that ends “Before Our Eyes,” launching us into the poems that follow. “[P]oetry / I know something about,” this passage begins, and he goes on to define the art in five distinct, complementary ways:

The act of forming

imagined language resisting humiliation.

Fading browns and reds, a maroon glow,

sadness and brightness, glorified.

Voices over charred embankments, smell

of fire and fat. The pure metamorphic

rush through the senses, just as you said

it would be. The soft subtle twilight

only the bearer feels, broken into angles,

best kept to oneself. (125–26)

The first of these definitions signals the poet’s social imagination. Poetry is not just (as Stevens said) the “act of finding / what will suffice,” but an “act of forming” in the name of resistance, of justice. The second definition, by contrast, starts with aesthetic perceptions, but does not end with them. Poetry, it declares, consists of emotion and color “glorified,” a word that Joseph uses in its full theological sense, as one speaks of the “glorified” body of the risen Christ. The third definition, in which poetry is a matter of “voices,” joins the social and the aesthetic. Those voices might be crying out in pain, victims of conflict, but they remain ambiguous, rising “over” the destruction, just as that “smell / of fire and fat” might be either human fat or a touch of savory beauty. (Joseph has given us a scene like this once before: “I fire my rifle into the sun, / shout God’s name, / return to ruins to roast a lamb,” he wrote in poem 3 of “The Phoenix Has Come to a Mountain in Lebanon,” in Shouting at No One, 27). Poetry is “the pure metamorphic / rush through the senses,” Joseph now says, ascribing that definition — in which, one notes, the senses give us access to something beyond them — to an unnamed “you,” a gesture which makes poetry a social bond, a promise that has been kept, no matter who this “you” might be. Picking up on the mysterious identity of that “you,” Joseph ends the passage on a hermetic note. Poetry is “[t]he soft, subtle twilight / only the bearer feels, broken into angles, / best kept to oneself,” he writes (126). Yet rather than shut us out, this withdrawal into privacy draws us closer, tempting those with ears to hear to listen for hints in the words that close the poem: “For the time being, / let’s just stick to what’s before our eyes.”

The “what” that this implies, as the lines above it have shown, is already quite various, and not at all limited to Gilbert’s pair of “ephemeral impressions of colored light” and “social chaos.” The act of “sticking to it,” likewise, may sound reductive at first, but has already turned out to be redolent with aesthetic attention, social solidarity, and hints of the sacred. Joseph reinforces each of these multiplicities by following “Before Our Eyes” with a short, hermetic lyric, “A Flake of Light Moved,” whose four stanzas touch on, respectively, color, love, mystery, and revelation. The nature of that revelation, “[a] flake of light” that interrupts the “[d]iagonal shadows” and “deeper blackness” of the sunset scene, remains hidden from us, but its effect on those who see it is quite clear. “Everyone / watched,” Joseph writes, “as if hypnotized, and more, / much more, than that” (127). David Yezzi’s review of Before Our Eyes balks at this poem. “Given the salt in the rest of the volume, it’s hard to swallow such uncut sugar,” he quips.[37] But throughout the volume Joseph uses such instances of grace to buttress and nourish a self that can then open itself to, bear and transfigure, the salt that Joseph more than delivers, and that Yezzi prefers. In “Brooding,” a lovely erotic memory leads into thoughts of theology, then light, and only then into the social realm, by which the speaker reports himself “unfazed”:

[…] one rose

in the crystal vase

in the room where

she stood before me,

legs slightly apart,

golden dusk all over us

when she insisted

not to go on talking

as if I was dreaming,

arguing the Summa

Theologica’s proofs

that God is the love

she was brought up on,

she and I. Always

this point of departure

always, ceaselessly,

pushed toward

particulars of light

insistent emotions

sometimes abstracted

rarified air.

Not at all fazed

that man on Grand Street

is yelling “Eloi,

eloi, lama sabachthani,”

I’ve heard the words

before. Blocks away

substance dealers

finance insurance

companies, purchase

pension funds. (150)

A similar trajectory shapes the three-part poem “Movement in the Distance Is Larger Up Close.” Here Joseph starts with “[a] certain splendor” suffusing everyone at the “Café Fledermaus” — a scene that is ripe tart critique, even for parody (173). But after a long, wide stanza of the speaker’s “rampage within [him]self” against the times, it is the power of “boundless happiness and joy” that brings him back, with real care, to the mixed urban world around him (174). “The leaves in the park deep, irascible mauve. / The crippled unemployed drawing chalk figures / on the Avenue,” he notes, refusing to rank the two. (Even the unemployed are engaged in poesis, mustering art as resistance, after all.) The public space that includes them both is, the poem concludes, “Where we ought to be.”

Now that Joseph’s first three books are bound in a single volume, one can easily flip back and forth between the self we meet at the start of his career — the “poet of heaven,” before and after his exile — and the one who leaves the stage in Before Our Eyes. Joseph links the two in resonant ways, not least by revisiting, in this third collection, the founding myth of the first. The revision comes at the end of “Generation,” when, after a two-page column of verse, a single quatrain breaks off and looks back at the historical sweep and dizzying “flux” of the poem as a whole. “So that’s when we got the idea in our heads / to be born,” this quatrain remarks, “not to let the sights / slip away, choosing in a badly measured time / human form over nonbeing” (140). Instead of the individual “I” of the early prefatory poem, a plural voice speaks; instead of birth as punishment, we find a choice to be born, as though incarnation were the only way for “nonbeing” to see, to remember, to embrace the “sights” that would otherwise be lost in the chaos of “a badly measured time.”

This mission — and that seems the word, in every sense — requires the self to be attentive, even vulnerable, to the disorder of history, precisely in order to counter disorder by spotting and presenting, again and again, glimpses of some redemptive alternative to it. In the final stanza of the book’s last poem, “Occident-Orient Express,” Joseph speaks as and offers an image of this closing vision of himself:

Against my heart I listen to you

all the time, all the time.

Against my brain, more visible than dream,

the present’s elongations spread

blue behind the fragrant curves

pure abstractions blast through

a fragile mind in a flapping coat

descending the Memorial’s steps

toward incalculable rays of sun

set perpendicular into the earth. (177)

As we might expect by now, this poet is a self-divided figure. “Against my heart” and “against my brain” are phrases that imply both intimacy and resistance (as in, “against my better judgment”); in each case, however, the self is now in a constant relationship (“all the time, all the time”) a “you” that seems simultaneously the world around him, a God or muse within him, and a beloved who embodies a little of all of these. (The combination is familiar in Montale, and goes back to Dante.) This self attends both to “the present” and to “pure abstractions,” and in both cases it does so with sensuous delight, ascribing color and fragrance and shape to both. A “fragile mind in a flapping coat,” this closing figure — of the poet? Of another? — does not need to claim grandeur or strength for itself. Rather, it lets that very fragility hold it open, vulnerable not just to the wounds of social history, but also to beauty and radiance, to what Wallace Stevens called “[a] light, a power, the miraculous influence.”[38]

As we might expect by now, this poet is a self-divided figure. “Against my heart” and “against my brain” are phrases that imply both intimacy and resistance (as in, “against my better judgment”); in each case, however, the self is now in a constant relationship (“all the time, all the time”) a “you” that seems simultaneously the world around him, a God or muse within him, and a beloved who embodies a little of all of these. (The combination is familiar in Montale, and goes back to Dante.) This self attends both to “the present” and to “pure abstractions,” and in both cases it does so with sensuous delight, ascribing color and fragrance and shape to both. A “fragile mind in a flapping coat,” this closing figure — of the poet? Of another? — does not need to claim grandeur or strength for itself. Rather, it lets that very fragility hold it open, vulnerable not just to the wounds of social history, but also to beauty and radiance, to what Wallace Stevens called “[a] light, a power, the miraculous influence.”[38]

As Before Our Eyes ends, this final self “descends” towards the earth, but the “rays of sun” that it moves towards also raise its sights up a “perpendicular” axis. A dozen years later, in 2005’s Into It, Joseph’s most recent book, that same self will grapple with the violence and aftermath of 9/11. It is the work of another essay to trace the results. For now, suffice it to say that the light that sets “perpendicular into the earth” at the end of Before Our Eyes points the poet’s path as the next book begins, with its opening poem leading him at once towards the pit of Ground Zero and into the world of poesis, “in it, into it, inside it, down in.”[39] The range of poetics and resources that he brings with him on that descent is unique, I believe, in American poetry: mythic-modernist, identity-poetic, and social/sacramental, each building on and looking back to the others. And as the end of “Woodward Avenue” shows, his latest work recalls and deploys them all, moving from an echo of Motown, the poet’s hometown music, into the mix of critical self-consciousness and sacred vision that Joseph, as no other American poet, seems able to supply:

A dance that you get to,

“The Double-Clutch.” Listen. Sure is funky.

Everyone clapping their hands, popping

their fingers, everyone hip, has walks.

Effects are supplied, both rhythmic

and textual. Another take? Same key?

Sometimes you’ve just got to improvise a bit

before you’re in a groove. Listen.

That’s right. It’s an illumination.

That which occurs in authentic light.

Like the man said. So many selves —

the one who detects the sound of a voice,

that voice — the voice that compounds

his voice — that self obedient to that fate,

increased, enlarged, transparent, changing. (18)

1. David Kirby, “Codes, Precepts, Biases, and Taboos: Poems 1973-1993 and Into It: The Double” (review of Codes and Into It, by Lawrence Joseph), New York Times, September 25, 2005.

2. David Lehman, “The Practical Side of Poetry,” Newsweek,September 22, 1986, 79.

3. Michael True, “The Limits of Language,” Commonweal, September 22, 2006, 31. In point of fact, True’s description is biographically inaccurate; neither Joseph’s grandfather nor his father ever worked in an auto plant, and none of his poems says they did.

4. David Wojahn, “Maggie’s Farm No More: The Fate of Political Poetry,” Writer’s Chronicle 21 (May/Summer 2007): 29.

5. Wojahn, “Maggie’s Farm No More,” 29.

6. Paul Mariani, “History and Language,”America, January 30, 2006, 32.

7. Wojahn, “Maggie’s Farm No More,” 29.

8. David Yezzi, “A Morality of Seeing,” Parnassus: Poetry in Review 19, no. 2 (Fall 1994): 83.

9. Roger Gilbert, “New Poetry and Modern History,” Michigan Quarterly Review 34 (2005): 272, 285, emphasis added.

10. Gilbert, “Textured Information: Poetry, Politics, and Pleasure in the Eighties,” Contemporary Literature 33, no. 2 (1992): 243, 249–50.

11. I borrow the phrase “breaking of style” from Helen Vendler, The Breaking of Style: Hopkins, Heaney, Graham (Boston: Harvard University Press, 1995).

12. In Charles Graeber, “Pulling the Words from the Ruins” (interview with Joseph), Downtown Express 18, no. 25 (November 4–10, 2005).

13. I take the phrase “refractory contraries” from William Arrowsmith in his translator’s prefaceto The Occasions xiii, by Eugenio Montale (1957; repr., New York: W. W. Norton, 1987). As Arrowsmith explains, Montale endeavored “to enclose the refractory contraries — public and private, external and internal, historical and individual, transcendental and immanent — within the confines of the poem”; the passage is quoted by Joseph in “Notions of Poetry and Narration.” Often Joseph will make a Montalean attempt at enclosing contraries in a single text. When he does not, this is often because the contraries in question are dispersed across the book as a whole.

14. Joseph, “What’s American About American Poetry?,” Poetry Society of America.

15. “Lawrence Joseph,” Contemporary Authors Online (Gale Group, 2008).

16. Jonathan Galassi, “Reading Montale,” inCollected Poems: 1920–1954, by Montale, trans. Galassi (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2000), 417.

17. Reprinted in Joseph, Codes, Precepts, Biases, and Taboos: Poems, 1973–1993 (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2005), 3. Unless otherwise noted, citations to Joseph’s poetry are taken from this collection.

18. Galassi, “Reading Montale,” 415, 417.

19. Richard Tillinghast, “Five Poets of Our Time” (review of Shouting at No One, by Joseph), Michigan Quarterly Review 23 (1984): 596, 602–03.

20. Graeber, “Pulling the Words from the Ruins.”

21. Michael Hamburger, “Lost Identities,” inThe Truth of Poetry: Tensions in Modern Poetry from Baudelaire to the 1960s (1969; repr., Manchester, UK: Carcanet Press, 2004), 42, 44.

22. Hamburger, “A New Austerity,” inThe Truth of Poetry,220, 265.

24. T. S. Eliot, “Preludes,” in The New Anthology of American Poetry: Modernisms, 1900–1950, ed. Steven Gould Axelrod and Camille Roman (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2005), 398, 399.

25. Graeber, “Pulling the Words from the Ruins.”

26. “Eugenio Montale: An Interview,” inThe Second Life of Art: Selected Essays, ed. Jonathan Galassi (New York: Ecco Press, 1982), 310, 311.

27. Hayden Carruth, Selected Essays and Reviews (Port Townsend, WA: Copper Canyon Press, 1995), 78.

28. Lisa Suhair Majaj, “Arab Americans and the Meanings of Race,” in Postcolonial Theory and the United States: Race, Ethnicity, and Literature, ed. Amritjit Singh and Peter Schmidt (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2000), 320, 330.

29. Wallace Stevens, “Gaiety in poetry is a precious characteristic …,” in Wallace Stevens: Collected Poetry and Prose, ed. Frank Kermode and Joan Richardson (New York: Library of America, 1997), 920.

30. William Butler Yeats, “Meru,” in The Collected Poems of William Butler Yeats, ed. Richard J. Finneran (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1996), 289.

31. See Frederic Jameson, “Postmodernism, Or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism,” New Left Review I/146 (July–August 1984): 59.

32. The eyes / I’s pun is one that Joseph learns, perhaps, from the title of a book by Louis Zukofsky, I’s (Pronounced ‘Eyes’) (New York: Trobar Press, 1963).

33. Gilbert, “New Poetry and Modern History,” 285.

35. In “The Language of Redemption: The Catholic Poets Adam Zagajewski, Marie Ponsot, and Lawrence Joseph” (Commonweal, May 12, 2003, 12), Andrew Krivak briefly discusses Before Our Eyes as marked by a “prophetic” voice. The ideas he cites from Paul Mariani about “sacramental language,” which he does not apply to Joseph’s work, have also been useful to me here.

36. Quoted in Krivak, “The Language of Redemption,” 12.

37. Yezzi, “A Morality of Seeing,” 88.

38. Stevens, “Final Soliloquy of the Interior Paramour,” in Wallace Stevens: Collected Poetry and Prose, 444.

39. Joseph, Into It (New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2005), 5.

An introduction to Lawrence Joseph

Edited by Eric Selinger