Openings: Some notes on the political in 'Drafts'

October 21, 2010: An invitation and a beginning

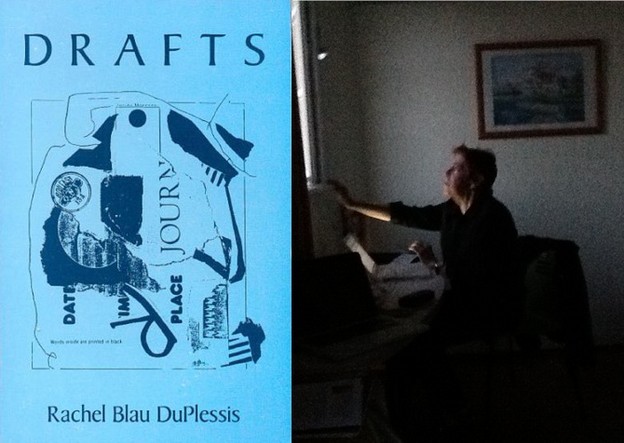

It’s kismet. When I left the Poetry/Rare Books Collection a few days ago, Jim gifted me with a signed broadside of Rachel’s poem “Some Codas,” illustrated with a detail from Duncan’s drawing for the cover of his Fragments of a Disorderd Devotion. And now — upon returning home after a month in Duncan’s archives at Buffalo and Berkeley — I have received Patrick Pritchett’s invitation to write about Rachel’s work. She was the first to give me permission to do much: to read Duncan, unafraid of other’s scorn for his romanticism and, yes, effete poetics (“He’s just a shrill queen. I guess that’s why I don’t like his work,” another mentor had admitted); to embrace the possibility of becoming a “poet-critic” (though the institution too often squashes my double claim, robbing me of time for the first); to know that thinking poetry is living with it, in the totality of language and on the page; to recognize, and challenge, the religiosity of minority identification through the mechanism of the word (though without trusting entirely in what Jolas had called “the revolution of the word”);[1] to experiment out of necessity as demanded by the poetic or even the critical project at hand, not out of faddishness. These were her lessons first. My study of Duncan over the years (fast coming on “decades”) has underscored them, emphasizing their relevance not just for me but also for the art, generally.

So the task is simple: to write in the spirit of Duncan’s notebook studies (of Olson, Levertov, Eigner, Dorn, Dickey — Dickey?!?! —, Blake, Dante, Whitehead, Boehme, Cassirer); of his daybooks on the War Trilogy in the second section of the H.D. Book; of End to Torment, H.D.’s own memoir of her life in poetry with Pound; of Oppen’s and Creeley’s daybooks, to which I keep returning; of the openness and opening and process so important to both of us.[2] And so, I will write my own étude (a favorite word Duncan used to describe his studies) of Rachel’s work. For many reasons, I must keep it personal: not out of overfamiliarity or lack of respect, but for reasons quite the opposite.[3] More than any other poet, critic, or teacher, Rachel has directly shaped my intellectual and artistic consciousness, my author-ity. But she also was one of the few who have modeled, more by example than by explicit instruction, the degree to which personhood exists in tension with subjectivity, personality alternating with impersonality. I will refer to her as she sometimes signs herself, after another: RBD.

As I reread some of her Drafts, this process will be a testing ground for ideas I keep butting up against ideas she, in one way or another, set into motion — set me into motion after — years ago. Process is a procès, as Deleuze and Guattari would say; productive and politicized thinking really is shadowed by a trial, a series of experiments working toward a judgment.[4] RBD would appreciate that duality, she the lover of what she called “shadow words” in the seminars I took with her. [January 15, 2011: Or, as she puts it in “Draft 35: Verso,” “shadow things inside behind the said.”][5] It’s fitting that I use the essay form to conduct these proceedings. I have repeatedly told my own graduate students the now perhaps apocryphal story of when she sat me down — in 2000 or 2001, sometime before I finished that trial called dissertating — to tell me I would always have a hard time writing books. “You are a processual writer,” she diagnosed. Correctly. “You are a writer of essays.” A bewildering observation, especially for a fledgling academic whose career has depended on producing more books read by fewer people, to satisfy administrative fetishists and bean counters. I am writing yet another now. In contrast, my own poetic “career” has been marked by a near-refusal to publish because, as Lynne once joked with me, there are too many “novels (here, read: poetry volumes) of inexperience.” Stevens is my standard. (NB: Harmonium was published when he was forty. I have two more years. One more, by the time this appears.)[6] RBD’s warning may have flummoxed me back then, but now I understand better. She truly appreciates — and models — the spirit behind the word essay. “These are works of ‘reading’ — for essays are acts of writing-as-reading. Acts of trying out, as the French root essayer says.”[7] She doesn’t say as much here, but she knows that that “trying out” is also a putting on trial. There’s judging in testing. Not just a judgment of the subject about which one is writing, but also a judgment — sometimes mixed, always shifting — about what one is writing, that is about writing itself.

Alongside RBD, I want to consider two others who are cornerstones for her work, as well as mine: Duncan and Oppen. Patrick says my plan is to read her between her “Objectivist and Projectivist modalities.” I want to see it less academically, more as a vocation. Better: as a testing ground, a field of experiment. Oppen and Duncan will enter this study only peripherally, in-forming (as Duncan would put it) my reading, just enough to track developments in RBD’s writing. She herself does not distinguish absolutely between objectivism and projectivism. Take, for instance, her characterization of Oppen’s work as “a kind of ontological arousal to thinking itself — not to knowledge as such but to the way thought feels emotionally and morally and processually in time.”[8] That is to say, she, too, sees this “objectivist” as a process thinker, one who works in time through the medium of thinking, of consciousness. Much of what I’m working through now in my own work on Duncan has to do precisely with this idea of consciousness and process as constitutive of his imaginative and visionary mode of projective verse or, more accurately put, field poetics.[9] So, indeed, these two shared predecessors’ examples, poetics, do converge. At the point of consciousness.

Of course, there are differences between Oppen and Duncan. The former gives us the immediacy of word, not as object but as “it”: poem as discrete series; ephemera and phenomenon; a standing still to contemplate; Heidegger’s notion of art as supplying an opening in the pause, “The art work opens up in its own way the Being of beings. This opening up, i.e., this disconcealing, i.e., the truth of beings, happens in the work. In the art work, the truth of what is has set itself to work. Art is truth setting itself to work.”[10] The latter appropriates this philosophical argot of What Is. Rather than a prophetic revelation breaching reality or reaching out to readers through objects and things, though, he sees it as the field itself: the open series; the unfolding of perceptions and consciousness; a continually grasping at one’s physical and linguistic environs to make them known, to make them meaningful, or simply just to make them; Whitehead’s idea of experience and environment as recursive, mutually affecting one another and thus impelling process: “Also in our experience, we essentially arise out of our bodies which are the stubborn facts of the immediate relevant past. We are also carried on by our immediate past of personal experience; we finish a sentence because we have begun it. The sentence may embody a new thought, never phrased before, or an old one rephrased with verbal novelty. There need be no well-worn association between the sounds of the earlier and the later words. But it remains remorselessly true, that we finish a sentence because we have begun it. We are governed by stubborn fact.”[11] Oppen and Duncan conceive of action differently, but they share the similar idea that action is being, the poetic act makes existence articulate. For them, such a notion of action is the extent of the poetic event. Whether meaning comes staccato, moment by moment, or all in a flow, whether it emerges from the field or constitutes the field itself, is irrelevant. Such distinctions are based on rather minor differences for poets and philosophers and academics to quibble over. There is a place and time for that. What matters most here, in these reflections on RBD, though, is the common ground Oppen and Duncan share: that action and being are rooted in meaning.[12]

Can meaning be the bottom line, though? Both Oppen and Duncan are stumped, stupefied, silenced by one common “problem”: politics. If poetry is meaning, if the poem is the event of Life and of Life’s Language voicing itself meaningfully, can politics play a role in poetry? Is politics part of Life (with a capital “L”)? Or, does introducing the political into the poem render existence into merely existentialism (of an angsty order)? Does politics reduce the poem to the effluvia of the person? That is the conclusion both Oppen and Duncan resist. Sometimes that resistance leads only to stoppages. Best-case scenario: writer’s block (viz. Duncan’s major freeze, the year-long stoppage when writing “Passages 26, The Soldiers,” 1964–1965; along with other, shorter moments of writer’s block … most occurring when he was lecturing for universities, a political as well as poetic lecture circuit, and working on poetics essays and his H.D. Book, whose political undercurrents have not yet received sufficient attention). Worst-case scenario: the poet stubbornly refuses to let politics enter the poem, is hounded by apparatuses of the state (including the FBI), is driven into exile, and falls silent (viz. Oppen, 1934–1958). Either kind of stoppage results from the poet’s obedience to the pressures of a patriarchal “Thou Shalt Not,” from perhaps his own unacknowledged belief that poetry is pure of the taint of the polis, an unrecognized acceptance of Plato’s decree of the poet as exiled from the Republic or Lenin’s decree exiling the poet from the Party. To lend such prohibitions any credence, though, would stop me — from writing, from thinking, from trying to answer in my own way Heidegger’s famous question: What are poets for?[13]

My critical point of departure is this, then: though RBD herself is a product (and shaper) of second-wave feminism, for which “the personal is political,” she has devoted her work to avoiding the reduction of either politics or poetry to the personal, to personality. As she puts it in her essay “f-words,” “positionality, not personality is central.”[14] It is an argument she has long maintained. Just note her response almost two decades earlier in “Sub Rrosa” (1987/1989) to the second-wave–style assertion that “To read as a woman is to rupture this expected practice [i.e., of all women having been acculturated to read like men].” As she goes on to wonder, “But to read as what woman? A woman? Is that phrase generic or specific? […] It seems amazing even to imagine one, but to imagine hundreds is gratifying. So I read as one imagining others.”[15] This stress on the imagination, on imagining herself not just as an Other (Rimbaud’s “I is an Other”) but as many others (the lower case “o” is more appropriate, I remember her cautioning me early on), is the route by which politics enters the field of Rachel’s poetics. Or, in the least, it is the means by which she attempts to make a place for politics in poetry, in making the Being of Oppen and Duncan more becoming, more multiple, more extensive.

Such becoming does not just occur in the nomadic sense of endless flows or a perpetual shedding of one’s skins. One must stop, too. Not all subject positions can be imagined, let alone assumed. And every position one finds one’s self in is a location, a stopping-ground. Even Deleuze and Guattari write about those nodal points breaking up the lines of flight, where one engages meaning and sense, so as to start off again on a new tack.[16] When RBD stops, and knows she is stopping, she is processing/procès-ing the situation. She produces the possibility for this stop-and-go, by formally crossbreeding Oppen’s silent seriousness (discrete series, measured and marked by silences) and Duncan’s open duplicity (open series, garrulous and riming with double meanings). The result: her continuous poem, Drafts. Let’s not give “it” or “What Is” the last word, she implicitly proposes. Let’s see if “it” can talk itself out of a bag — over and over. In this way, her poem doesn’t have just one opening. (Does any body?) Instead, language is compelled to speak, repeatedly. The poem as a process of drafting opens multiple shifting possible political or politicized spaces she and I, one of her readers, can inhabit. We don’t have to make a political space sui generis; we don’t have to assert our personality. Rather, spaces open and we migrate into them to fill, to occupy, them. Such political aims are double-edged swords, though: in any poetry, politics often becomes an egoistic staking of claims. Invested in a search of places to occupy we imitate the modality of imperialism and neoliberalism. With all these openings, then, her poem-in-draft also gets mighty drafty. Who can say, then, if this space of political possibility is at all habitable?

Intermittently, I’ll test these waters. Getting my feet wet, as they say, from the start of Drafts. One day at a time.

October 25, 2010: Close listening

The light

Of the closed pages, tightly closed, packed against each other

Exposes the new day,

The narrow, frightening light

Before a sunrise.

— George Oppen, “Of Being Numerous”[17]

It’s troubling — this image of a book as the embodiment of openness in closure. Not just shut, rather “tightly closed.” Suffocating, claustrophobic. Yet, possibility — slim, like Oppen’s own volumes before they were collected, yet still disturbing — is glimpsed in a sliver of light escaping from the closed book. Not that the light originates in the book. The preposition — of — has the utmost importance, as most of the “simple” words do for Oppen.[18]

Moments like this are what attract me to whatever political possibilities poetry has. The derision I’ve heard from friends and colleagues and readers, even a few of the smarter and more cynical students, about my audacity for believing not just that poetry has value but that hope does, too. These critics also find unthinkable one of my articles of faith: that poetry’s value owes to the fact that it’s a vehicle of hope. A mode of transport. True, my attitude is romantic. Yet, if both poetry and hope are worthless: why read?

Forget the old question, Why write? Why read?

Clearly, few people are reading. I’m not concerned with statistics, which actually show that more people are buying, maybe even reading, books in different forms, whether digital books or “P-books” as librarians now call the heavy old print things, according to Nick.[19] What I am most concerned with is RBD’s concern, too: not just reading, but really reading. Paying attention. [February 24, 2011: How did this not occur to me then? A closeness to remedy closure. A close reading that, in attending a text, is a form of opening, of undoing the claustrophobic closure and of letting loose the hope Oppen imagines in his tightly shut book.] These two related faculties — reading, attending — bring Oppen and Duncan into conversation. Both demonstrate an incredible care for what’s there, object or word … even phoneme. And that’s where the lesson, or the hope, lies. Listening closely to Oppen’s “Of Being Numerous,” though, we rediscover that hope is actually strange and unsettling. My boldness only lies there — in knowing (not believing) that good reading is close listening: aud — the morpheme from the Latin for “bold” is at the root of both audacious and audible. If a poem were not bold, it could not be heard.[20]

There are ways to smother boldness, though. Overcooked cuisine. Stewed poetics. That new world is almost (important qualifier) shut up, tight. To hear it, we must be on the lookout. Reading as synaesthesia, then: where vision must aid audition.

Back to Oppen’s simple preposition — of. It begins, and proliferates throughout, “Of Being Numerous.” Of often appears at the beginning of his lines. It is a hinge or a connective tissue, easing us through his enjambments and carrying us along. Through the title, it even carries us from this world and onto the world of the page, connecting both. Yet, it also announces a breach. The definition of an ideal numerousness starts here, with the titular of. Each appearance of the preposition at the head of a short line turns that line into a fragmentary proposition which, in its very lightness, bears ontological weight: “Of an infinite series”; “Of the mineral fact”; “Of anything that happens”; “Of the singular” … to cite but a few.[21] Continuity and breaking: the discrete series’ definitive quality. One might see it as the space of interruption, an eventful space in Badiou’s sense.[22] That would make sense, for there is room for Oppen’s series in the work of a philosopher who derives his ontological, ethical, and political work out of set theory. For Badiou, the event is the site where a militant ethics irrupts, intruding upon the logic of the established set; and in its demanding the militant’s fidelity, it heralds a political shift. This metapolitical event is not only unpopular but also dark, apocalyptic, signaling an endtimes shift in the world-as-we-know-it. In many ways, there is a consistency between the idea of the mathematical philosopher and the vision of the poet who cites the mathematics. However, Badiou does not see an event as multiple. It is utterly singular. It sets into motion a singular truth-procedure. In addition, for him, as I understand him, there is but one set, one monotonous reality, interrupted by the event.

So, despite their mathematical affinities, there is a major difference. Oppen’s world is a series, not a set. There seems more room for multiple singularities and events, for multiplicities, more than what Badiou allows for. The poet proposes that the singularity is the individual herself; to some extent she determines the meaning of of, rather than must be faithful to a meaning coming from the eventful irruption. (I’ve always felt that, despite his CPUSA membership and activism, Oppen was more of an anarchist. More like Rukeyser, an anarchist communist or anarchist socialist since the advent of the Popular Front. So different from a Maoist May ’68-er like Badiou.) And that meaning can change, thus multiplies. If this of is a space, it cannot unilaterally demand our fidelity (too much like “fealty”) or make its claims on us. The space is not the One. That is, after all, the trouble with the nation-state, with the cityscape, with any authentic or exclusionary set:

We are not coeval

With a locality

But we imagine others are,

We encounter them.[23]

If that locality is an event, we believe we “encounter” it and those who belong to it. (Thus is the rhetoric of the imagination of extremist jihad and of mainstream Western/US imperialism.) But if this event, this “locality,” moves and shifts individually with those who experience it, then the possibility is always multiplying, opening up, over and over again.

RBD attends to Oppen’s tricky preposition and proposition early in her Drafts and she — like him before her — tries to make the word of do so much.[24] Mostly, though, she rejects his ontological register. For RBD, of is a more material matter than even when Oppen gives it substance by setting amidst these prepositional phrases a simple date — “‘1875’” — a date that is actually set in stone, the date marker on the Brooklyn Bridge’s Manhattan Tower.[25] Here historicity and materiality enter the poem, both monumental and grounded (via the reader’s understanding that the significance of this date) and adrift (yet another signifier, a detail on the page). RBD, in contrast, tries to give the word of even more of a material existence, and does so by pushing it beyond its possessive denotation. In Drafts, of is a synecdoche for the space of the objectivist’s city, the silent placeholder of the inviting thing-in-itself. But this space is not for resting in; rather, she’s gotta keep on walking.

A silent space (I

walk here) populous.[26]

RBD’s is an ambulatory of, then, able to be detached from signification overly determined by possessive relations. In this walkabout, though, she’s not looking for a vision. Or, at least, I don’t think she should be. (She herself doesn’t rule out that possibility.) It would be more exact to say that she’s trying to put reality into motion.[27]

So, RBD’s of, as a spatial entity, has more of a materiality to it than Oppen’s; yet, curiously, it floats about more than his does because she refuses it to be a sign of attachment, possession, even objectification. His of is embodied as a sort of stone-seizing Excalibur, mid-river outside Brooklyn, native to both him and her; thus, his of comes to be more One though it’s outside — while inside — city limits, between the boroughs where they grew up and where my husband and I now sometimes live. Yet, although her of is not possessive, its placeholding function anchors it. RBD is akin to Mme Bovary, then, or, Walter Benjamin. She is our flâneuse, strolling the arcades. She anticipates this move, too, with her essayistic wandering through, and wondering about, the prose units she dubs “arcades” in “Blue Studio: Gender Arcades.”[28] This is her open letter response to Barbara’s questions, which themselves seem to originate in a concern that echoes Heidegger, with a crucial distortion: What is a feminist for? In “Draft 3: Of” (Toll), RBD names this topology the feminist poet surveys and wanders the “langdscape” (20). It’s a too-awkward pun I can’t wrap my mouth around. But she’s not window shopping. She belongs to this space, is of it; yet, in keeping with the dual properties of this preposition, she is also disconnected from, and set adrift in, this language-scape which cannot possess or make any claim upon her (or her upon it).

Hard to get home; but this is, this travelling

of

is

home.

The streets the malls a homey homeless home

ahung with things. (21)

For some reason, I cringe at how this “home” degenerates in its proliferation (“homey homeless home”), now awkwardly reattached to the “things” of consumer capitalism. The placelessness of this exile in late capitalism is hopelessly grounded, attached to relations of possession by the very space of of, the preposition that set her free.

Ironically, then, the poem’s political hope, as announced here, is in opening spaces that always foreclose opening, in trying to move beyond but keeping tied to, in relation, to the socius we wish to escape. If only we could cut the fucking cord! But RBD knows, her Drafts signal upfront, that it’s not as easy as that. For the opening pages of “Draft 3: Of” is bracketed off, and running vertical in the left margin is one word: “Cut” (19). Yet, she can’t (or won’t?) make that excision. They still are on the page before us. An abandoned edit, though the desire to enact it is still signaled. It’s not the content that matters — it is that these lines are of this poem, just as she is of the land of malls and city streets that both beckon to and disgust her with their unrelenting commercialism. Commodities all “ahung” in plain view, a perversion calling to mind a pornographic “The Night Before Christmas.” (What if it weren’t “stockings” that “were hung by the chimney with care …”? What if something else, something signaling a sizeable endowment, were hung in those windows? As if our Mme. Bovary were strolling past Christopher Street’s sex shops …) That “ahung” (ahem) also has me keeping an ear out for the ache, or perhaps the tsking chk, that seems to be needed to be articulated here, to make this ahung an Achtung: Attention! This hurts! Or, Paying attention hurts!

Navigating this “langdscape” entails recognizing the doubled and duplicitous nature of language, the only tool at our disposal. Our ofs can connect us and set us free. But they also tie us to that from which we would be free, especially when our ofs bring us back to our hankering for possession (and possessives). Which side we land on depends on how we attend to the language. Is this cause for lamenting? For mourning the loss of political possibility? For scorning those who dare to hope? Nah. It’s simply realistic. Funny word to describe a poet, huh?

November 2, 2010: “Between what and what” … or is it just “what”?

But there is an aspect of that realism RBD herself doesn’t attend to. For, despite herself, her work tends to forget the dual nature of of, transposing it. That is, the specificity of the word to signal connection and disconnection often goes unheeded, and instead RBD forces poetry to signify liminally. Her sense of the “blue” — that space of hope in contending with the painful particulars of the situation one finds oneself in — is interstitial. When writing of the specific kind of realism (“urrealism”) of the poets under whose sign she thinks and writes — Niedecker, Guest, Oppen — RBD notes that they work “between vision and the real, between a spiritual dimension and a material(ist) one — a between that one might imagine as unstable, constantly under construction, difficult to sustain.”[29] However, putting that mode of engaging reality, that modality of realism, in some interstitial “between” space is not an urrealism but a kind of irrealism or an unrealism that risks or aspires for transcendence. Well, it’s transcendent insofar as moving in this between is proposed as a means of moving beyond limits. As RBD writes in “Draft 18: Traduction”:

Lettres, j’entre

dans le passage

d’une langue

et de l’autre

à l’outre […][30]

The strangeness and stranger of the language one inhabits or seeks out (l’autre) serves as the passage (significantly, a Duncan word — the Duncan of the open series Passages) to the outside (l’outre), with which otherness rhymes — phonemically and meaningfully.[31]

This outside is related to her concerns with a particular kind of materialism, as modeled by Adorno. RBD is fond of quoting him. “How many times can I cite Adorno!”[32] Some of that fondness comes from a desire to write poetry, an activity she finds, as a cultural Jew, freighted with a particular difficulty and responsibility.[33] She embarks on this writing sensitive to, but challenging of, Adorno’s belief that poetry is forever impossible after the Holocaust: “To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric. And this corrodes the knowledge of why it has become impossible to write poetry today.”[34] But Adorno specifically judged lyric to be impossible, and, if we want to be sticklers, he actually judged all lyric, at least since the advent of late modernity and the rise of capitalism, to always be impossible. This is true because modern lyric, in a capitalist age, before Auschwitz and long after, is always already social. “My thesis is that the lyric work is always the subjective expression of a social antagonism,” and “A collective undercurrent provides the foundation for all lyric poetry.”[35] RBD is not exactly writing lyric, but, then again — this is partly what Oppen and Duncan bequest her — she’s not exactly not not writing lyric, either. She’s aware of the subjective mediation — personal, yet also collective — that stands in the way of aspiration of “the highest lyric works” in which the subject recedes and “language itself acquires a voice.”[36] Whether it is factually correct or not is immaterial for my understanding of the poem. I have begun to date for myself the advent of Drafts with the following statement from “Otherhow,” an essay first drafted in 1985, the year before the date RBD attributes to the first Drafts’ composition:[37]

(No more poems, no more lyrics. Do I find I cannot sustain the lyric; it is no longer. Propose somehow a work, the work, a work, the work, a work otherhow of enormous dailiness and crossing. All the “tickets” and the writing. Poems “like” essays: situated, breathless, passionate, multiple, critical. A work of entering into the social force of language, the daily work done everywhere with language, the little flyer fallen to the ground, the corner of a comic, a murder, burning cars, the pouring of realization like a squall green amber squall rain; kiss Schwitters and begin)[38]

Drafts does not abandon lyric, not as RBD announces that intent here; but the poem does stay true to the spirit of this pronouncement, it does register the impossibility of an idealized “pure” lyric. “Kiss Schwitters and begin.” Hers is a feminist poetic version of Schwitters’s merzhaus. Hers is an assemblage forming a household built out of love, out of detritus, out of the unnoticed and quotidian. And, as the poem comes to deal with it more and more as the first volume, Toll, progresses, it is a poetic structure also constructed out of the forgotten and the silenced. Such an assimilation is the responsibility of the writer: “who can be witness / after the eclipse of witness // cannot not speak.”[39] RBD’s thinking about the materiality of (lyric) poetry — a materiality that intervenes in the disappearance of the subject (both the author’s self and history’s “others”) and of letting language just speak of its own accord, “a work of entering into the social force of language” — anchors her critical work, too. She even gives it a name — social philology — and uses that concept as the matrix through which to explore gender, race, and religious culture in modernism.[40]

This kind of materialism — I’m fond of it, too, but let’s call it what it really is: immanence. Adorno does not give up his Hegel. (For that matter, neither does Benjamin, whom RBD’s also fond of referencing.) This is more than an academic, genealogic point. And it’s more than the residua of Marxism, Adorno as merely a continuation of a historical materialist tradition of standing Hegel on his head. For the Frankfurt School, especially for Adorno and Benjamin, metaphysics must inflect materialism … especially when it comes to art. Lyric poetry might be impossible, but we still long for language to have its own say, to pronounce itself, no matter how barbaric or irresponsible such a wish is because it causes us to willfully turn away from social justice and human depravity and criminality. Art lies to us insofar as it encourages this wish. But that is a necessary lie, Adorno reflects (he calls the lie art’s autonomy), since it is under this cover that it ushers in a World Spirit, supplies the truth whereby discourses and systems are disrupted, transformed, re-formed.[41] What is more, the lie about art’s embodiment of ahistorical truth lets its historical (dialectical) content serve as the very substance whereby truth enters the scene, disrupting us and the systems or orders to which we belong.[42] Thus, art lays bare — calls into question — the logics of a regime of truth, as Rancière would put it, by showing us what we’ve forgotten.[43] We must then be faithful to the truth that emerges there, Badiou would say — and so, in our fidelity to the vision it embodies, art becomes political.

But Rancière helps us see the limits of immanence à la Adorno or Benjamin or of the event à la Badiou (for his event is no immanence of truth-content but is a truly disruptive procedure): truth exists only in regimes. To believe there is an irruption or irruptive emergence, an intrusion of truth, via art is to believe that art is a portal through which a monistic truth can affect all parts of our experience. It is to conflate the work of art with the work of politics, thereby erasing the fact that the art and the politics are both struggles, but they are only analogous struggles. That is Rancière’s useful reminder. Politics may elucidate art, and vice versa. But they are not the same. The two are and should be related. But it is a risky business to conflate them. RBD’s “between” is a between-times — between now and future, social pain and political redemption. One might think the between is a placeholder, marking a space or a gap between two like but not identical terms. But if the between is a space of immanence, the space through which the truth enters and thus transforms the poetic and the social worlds, it actually risks a dangerous conflation.

I wish I had my copy of Aesthetic Theory here with me now. (The danger of writing at a remove from most of one’s library for weeks at a time …) At one point, if I remember it correctly, Adorno tries to talk himself out of the immanence corner.[44] To say that art presents the structures of difference from which we (in reading or viewing the aesthetic text) glean difference, possibility, hope. Thus, it is materialist. But how did that structure get there? Adorno (after Marx) says it is the World Spirit. And this is when my Marxist students get angry with me, because I reply: “Nonsense. That’s not materialism. That’s religion.” That is, that’s Marxism-in-spite-of-Marx. That is, you were taught to believe the World Spirit is materialist when it’s stood on its head. It’s not. It’s still monistic, the stuff of theology. Reality pluralizes. If we are to believe that there is a materialism in this scenario, this stuff of immanent vision already has to have been there, was already real, was part of the structure of the life lived. And this is where the supposedly odious “metaphysics” of a William James or Whitehead or Dewey — Duncan’s chief influences, my pragmatists — pop up. Those structures already were part of the fabric of organic and social life itself. Artists, not art — makers, not the made — bring those sites of difference into the realm of their art. Through that art, they come into the fields (plural) of readers’ consciousness. Whitehead’s word, the one to which Duncan gravitates: the difference is apprehended, and thus folded — a concept RBD gravitates to — into consciousness, and thus changing reality which is recursively constituted by subjects and objects that work on one another, through material interaction and through the participation of ideas — offering up data, receiving and processing data, re-visioning the word through the data, the newly re-visioned world sending forth new data, ad finitum. Rarely is any exchange a major change. Miniscule, but not insignificant. The process demands a constant working and reworking, a seeing and re-seeing. In an important but forgotten essay, Duncan, writing of Woolf’s aesthetic politics, beautifully calls it “an alchemy of in-formation.”[45] (RBD would appreciate his thinking through Woolf. But his Woolf is the author of Three Guineas and hers is, primarily, the author of A Room of One’s Own.)

When we’re so much of that slowly transforming field of consciousness, we can’t be between here and there, now and future, pain and utopia. We just are. The future seeds the present, as does the past. We just work the ground.

As my mentor, RBD instilled in me my suspicion of rhetoric. Now I tell my students simply this: Every poem fails, and that is why they all are generous gifts. For their failures open opportunities for our thinking. She may say she’s working on a beyond in between, but that’s only because she’s invested in seeing her poetics and politics as similarly invested in using that between to get outside. That is to say, her project is still one of liberation.[46] I’m just as much Foucault’s pupil as hers, though. Freedom need not be, in fact never can be, liberation. Foucault addresses this when speaking not about the second-wave feminism with which RBD was allied but instead about its sister movement, the movement that made my thought — indeed, my very life — possible: the American Gay Liberation movement.[47] It’s no exaggeration to say “my life.” If it were not for the GLF, the GAA (the Gay Activists Alliance), or later Queer Nation and ACT UP and GMHC (Gay Men’s Health Crisis), or any number of post-Stonewall movements and organizations, I surely would be dead by now, another statistic of a self-loathing gay suicide, a hunted down faggot loathed by the world, or another victim of the Plague. Yet, I also recognize politics’ limits. I do not believe in liberation or the thought of any outside, even if it is only an enclosed outside between two defined spaces. (Philosophy, like poetry and politics, does come down to an article of faith. The will to believe — William James here — depends on what we can believe, on what’s observed, studied, experienced.)

I must see where in Drafts RBD’s thought betrays itself, goes against the logic of the outside/between, against the poem’s implicit romance of liberation in its romance of the between. That is where the politics of poetry is complemented by an ethics, the substrate of the political where collectivism meets individualism. In Drafts, one (liberation) is more conscious and declared and formulated, and the other (freedom) less conscious (not necessarily un-) and so more inchoate and grasping (a word culled from Duncan’s notebooks, when he was trying to make Olson speak to Whitehead, to make “apprehending” a physical and conscious affair).

December 7, 2010: Pause

In these last few days, I’ve returned to Drafts. Just in time to accompany RBD as she, too, returns to what she had already written so as to execute her folds. A confession, though: It’s difficult to sustain the concentration needed to attend the poem closely. I realized today that in length alone the four published volumes are longer than Pound’s Cantos. Excluding notes, though, they’re approximately the same: 800 pages. I am starting to suspect that I won’t read through the entire poem for this essay. My pages quickly (relatively speaking) fill up. At least whatever I produce here will be a beginning, a way of breaking the ice by asking uncomfortable questions and by demonstrating deep appreciations. But I’ve also been moving too slowly through the poem. In part, the work demands it, but I am also too distracted by my other studies — my chapters on Duncan for the anarchism book, my reading of Riding and Jolas (my present, nearly inexplicable obsessions — a few months ago it was Dahlberg). The questions these studies force are similar to what I’ve been asking about RBD’s between, though. Given her disdain for “pure poetry,” just how much is Riding’s conception of poetry actually a divorce from sociality, a metaphysical celebration? Even her post-poetic telling is rooted in sociality somehow — if for no other reason than the fact that strives for a critique of the masculine, in all forms of discourse and social being? Is Duncan’s construction of a space between prophecy and objectivism a metaphysic or an attempt to ground visionary experience? Is RBD’s between an unconscious opening from a social field onto a metaphysical other, or visionary, field? Similar, but different.

December 20, 2010: “the ethics of poetry being that fold”[48]

For some time — a few weeks, a month perhaps — I’ve been going over the last half of Toll to make sense of my notes in and about that portion of the first thirty-eight Drafts. What promising possibility lies behind, or obscured by, RBD’s problematic between? Reviewing my marginalia, I have found that my scribbles note my distance from, and critique of, “the game,” as I keep referring to it. Those instances are contrasted with my jottings and notes about “connection” or simply “here” — about those moments in the poem I am most drawn to because there and then I do not feel the need to perform as critic. Instead, I can just be RBD’s reader. “The game” is her self-conscious play, where the method is not only laid bare but also part of the poem’s polemic. Frankly, “the game” is where I get bored: it’s all so intellectual, self-reflexive. Boredom is not necessarily bad: it is a condition of the postmodern, or at least of my experience of the postmodern.[49] It is where my intellect gets carried away, in both senses of the phrase.

There is something about boredom in how Barthes discusses the text of bliss, which so often resembles what RBD’s Drafts are after. “Bliss is unspeakable, inter-dicted.”[50] It arises from the between places, and it depends — much like Drafts does — on a kind of shadowy haunting: “The text needs its shadow; this shadow is a bit of ideology, a bit of representation, a bit of subject: ghosts, pockets, traces, necessary clouds: subversion must produce its own chiaroscuro.”[51] Unlike the text of pleasure, to which it is related, interchangeable though not synonymous, the blissful text is asocial, struggling with its sociality.[52] It only traffics in and produces traces of the social — making the quotidian the material with which it works, thus pulling them into the shadows and the shadows into plain view. How like RBD’s “shadow things inside behind the said”![53]

This kind of postmodern text is the product of an avant-garde attitude, of a gaming that, in the end — at least for me — results in a kind of boredom, of an awareness that I’m being carried along by something else. This is its own kind of pleasure (rather: bliss or ecstasy, ek-stasis, standing beside one’s self so that the intellect can play freely). RBD engages her readers and calls upon us to recognize when this game is happening: “To pass beyond words / yet construct linkage, s meaning, s in unspoken space” (197 [sic]). But in the end it’s just aburrido. The real pleasure is had by the writer, when she is exerting her agency and engaging the language consciously. We, the readers, are left with the linguistic bliss. RBD’s the only one who can go “beyond words.” It seems that earlier I underestimated the degree to which she sets aside her authorial agency, the personhood of our experiences of writing. Here, I’m aware just how much the social traces are manipulated, and I am called upon to witness the performance. It’s not exactly authoritarian: there is no overt polemic or didacticism here. Still, all I, as reader, am left with after she’s had her full of play with meaning are the words themselves. The detritus, the leftovers of her game.

Let’s push this Barthes connection a bit more. The text of bliss “may well be, once the image-reservoir of speech is abolished, neuter.”[54] And the neuter is a category with which Barthes would struggle for the rest of his days, particularly after his mother’s death a few years later. Losing her made him revaluate bliss. His mourning produced a condition he described as “painful availability: I am vigilant, expectant, awaiting the onset of a ‘sense of life.’”[55] In lectures written soon thereafter when he was still in mourning, his concept of the neuter in the diaries would transform into a theory of the neutral, of subjectivity between action and passion. (Despite the slight change of name, though, Barthes is not immured to the gendered condition — or lack thereof — of this subjective attitude.) For him, the neutral becomes a means of dealing with living, with surviving. “Neutral: would look for a right relation to the present, attentive and not arrogant. Recall that Taoism = art of being in the world: deals with the present.”[56] In moving from neuter to neutral, Barthes is merely moving along the spectrum connecting bliss and mourning. They are not dissimilar. Both attend death: one (neutral) the death of the author, the other (neuter) the death of the mother. And both attempt to put one into relation with the present, which is, in the end, an impossible condition to articulate.

In those aforementioned moments where I noted “connection” or “here” in the margins of my copy of Toll are those moments where I came closest to empathizing with that moment of neutrality. And those are the moments when RBD stops; that is, those are the places where the game stops. Instead of self-consciously playing, those are the instances where she mourns. Or, perhaps she is just resting. (May she rest in peace.) After all, she does resist the characterization of her work as elegizing (“It is not elegy / though elegy seems the nearest category of genre / raising stars, strewing flowers ….” [111]). Instead, she is working, as she insists in the aptly titled “Draft 19: Working Conditions”:

The condition of work being struggle in time.

With loss.

And with these random findings. (124)

Or later in the same canto:

This is the work

This is the work

disfigured

form as experienced

struggle, over the mark.

And over the effacement[.] (128–29)

This category of “work” is very important for me, as it is for her. But for RBD it has a doubled significance, and for me it has only one. Her first: The significance of the game, of construction, of putting her will into it.[57] Her second (and my only): The craft that we go about, more often blindly than not. Struggling not with the materials (“the mark”) but over the void that those materials open out upon (“the effacement”).

And it is in the second sense — call it mourning, call it work, call it what you will — that she stops trying to go beyond, stops being so postmodern, and instead is caught up in the neutrality — and the neuter — of the writing. As she writes in “Draft 33: Deixis,” in my opinion the keystone of Toll:

the problem

is how to make poetry

constructed of It. (231)

And that “It” — capitalized — she borrows from our Duncan, our man who stressed so much the blindness of our craft. (For Oppen, I think, it would be less of a capital affair. Being, even when it’s eventful, is so much more common for him.) In a curious footnote nearby, Rachel points us to a passage from Duncan’s “The Self in Postmodern Poetry” that marks “it” as “The play of first person, second person, third person, of masculine and feminine and neuter[.]”[58] The feminist who gravitates to a voice wherein gender is not so much called into question as it is … lost. Or perhaps it is irrelevant? This neuter, this neutral of writing, is simple the ineffable present making Itself heard, if only for just a moment. “I would want to argue that it speaks in and through the now, perhaps just as it flicks into the then,” she writes in another note (Toll, 232n20). She’s not doing the speaking in these moments. The game ends so It can speak:

speak out of the it

speak out It.

Let It speak

Make it know and no. Now.

Make It (what) Knew. (230–31)

And when the game ends, so does the postmodernism. Pound creeps in (Make it new), inflected by Duncan (who only could make it old). Never a postmodernist (remember that is Olson’s neologism), Duncan thought himself merely a belated modernist. “I am far from that scene — far, indeed, it seems from [sic] me, from that scene — from being part of the New Poetry — for it has always been my imagination to be or take my allegiance from the Old.”[59] But producing that knowledge via derivations of how It’s found in what’s around requires some surrender of agency. One must give It priority over one’s self: “Let It speak.”

Rachel marries (yes, a gendered term and, in my experience, a heteronormative one, too; I have wed, but in the eyes of the state I’m not married) that tentative and mourning permission of working in a neutral condition, conscious of what one has lost and what others have lost (including their lives), with the more active gaming and joyful self-consciousness of willfully enacting a procedure.[60] And that procedure is? The fold. It is a measured selection, a correspondence between drafts to bring “the out-there” to “the over-here,” so as to produce an “ethical indistinction / between out-there and over-here.”[61] This comes about through a deictic procedure, an indexical matter of compiling and pointing. But I believe RBD’s description of the fold’s ethical nature is misleading, giving all the credit to the game that alienates me (let’s be honest), the game engaged only for her (or any post-modernist’s) pleasure: “making deixis the process of the between” (234). This folding helps me articulate the problem of the figure of the between. Rather than putting the between into process, folding, as RBD executes that procedure, is a coming into an ineffable and undiscoverable space. (The cross-gendering in my figure of coming into virgin territory, of penetrating a labial fold, is not to be overlooked.) That is to say, in folding, I don’t think she ever really points at It. It’s no definite object, and It’s not between her and her object or between me and mine (or between her and me, for that matter). No amount of pointing will ever suffice. Poetry can only wave its hands about to gesture at the general proximity of that in where It resides. Or poetry walks up to the hole and looks on it. Not able to see in. Just the surface.

But poetry also knows that there is an in there. Folding, or RBD’s game, is crucial for bringing her readers’ there here, into/onto the page. We may get carried away by the game, but the game also helps us know that It is so and that It is in there. And this understanding brings that there a bit more here. It makes that there more properly of here (to return to an earlier thread in my reading, to Oppen’s preposition). And so Drafts is not just a game of folding, rendering language into a new sculptural form as if writing were an exercise in intellectual origami. Rather, Drafts is also a poem of familiarities and intimacies, a process of bringing close what we’ve forgotten or held at bay. That process is trying at times, and it involves passing judgment: but mostly on our selves.

What Barthes knows, and what RBD knows, too, is we don’t just mourn the other that is lost. We work so as to mourn the loss of some part of ourselves that we had found in that other, over there. Barthes on mourning his mother: “Suffering is a form of egotism. I speak only of myself. I am not talking about her, saying what she was, making an overwhelming portrait[.]”[62] Working through that loss of some part of our selves, working to excavate where we are in the work, is not just the underlying motivation for the ethics of the fold, as RBD announces: “Thus. To be so. In is.”[63] Perhaps it is also the first step in making ourselves worthy, or of healing our selves, so that we — both the writer, who mourns, as well as the reader, who perhaps recognizes herself as that displaced subject whose lost-ness and distance of there-ness the author mourns — can be prepared for a politics.

Perhaps I’ve had it all wrong all along, and have failed to recognize the space from which I write. Perhaps the political nature of poetry owes not to its utopic vision, its serving as a vehicle for hope and for the possibility of joy. Perhaps the politics of the art does, after all, owe to the poem’s capacity to mourn, to provide us an opportunity, a preparation, and a companionship as we work through losses, injuries, even injustices. Writing from a queer position within the HIV/AIDS pandemic and the heterosexist and homophobic violence exacted upon those perceived as exhibiting gender and sexual difference, I should have been able to recognize it as such. Many who share a similar subject-position have noted that loss has been an appealing, if not the necessary, premise for a politics, especially for queer subjects.[64] I, clinging stubbornly to hope, have militated against others’ presentation of this conclusion as the only possibility. In the end, perhaps loss is where ethics intersects with politics, where hope becomes more realistic and grounded in the present. After all, having lost something, anything, is a precondition for hoping that a change may one day come. And that change attends our working and reworking the conditions with which we are presented, in the company of those with whom we share our efforts.

I think it is time to draw this record of my thinking about and my reading of RBD to an end. Reading Drafts, I have not found any ready or ultimate answers to the question of the political in RBD’s poetry, let alone “all” poetry. But it has all been a process to come to this point, then: I can now think of politics as, at least in part, a condition of mourning — of objects, of others, of unknowns, of our selves — and a condition of mourning a work or the work (working through the grief, the loss, the fracture of self, the self-displacement to make us present to our selves). Always at a loss, we remain open, persons in process. There still is a promise, then. But that eye to the future is matched with a responsibility not just to the past, but also to the fragility of the present, the tenuousness, even the mortality, of presence. Openness — a facet of what I have long thought of as “passion” or “vulnerability” — is the very principle wherein a poetic politics and a poetic ethics can intersect. Having worked with RBD to come to this articulation, I am now prepared to draw this opening of Drafts to a close.

It is hard to know why

this site is so implacable

but it is, clearly it is.[65]

post-face: March 26, 2011

Talisman: Tattoo 2 (Cariye Hamamı, v.2: When the lyric fabric deteriorates …)

for RBD

… and recalling the dead skin men sloughed

off: it, too, this sooth, this law, born of song,

in book shut tight, sweat

and unyielding devotion

bleeding now then

forever on the margins

of this runic caftan

in the gridwork between

circumscribed Solomonic stars

closely attending

where the Sultan’s breasts

would have streamed milk

had he sense enough

to mark textiles

with Tiresias’s semi-

permanent example.

June–September 2010; February–March 2011

1. Eugène Jolas, “Proclamation (‘Revolution of the Word,’ June 1929),” in Eugène Jolas: Critical Writings, 1924–1951, ed. Klaus H. Kiefer and Rainer Rumold (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1929), 111–14.

2. See H.D., End to Torment: A Memoir of Ezra Pound, ed. Norman Holmes Pearson and Michael King (New York: New Directions, 1979); Robert Creeley, A Day Book (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1972); George Oppen, Selected Prose, Daybooks, and Papers, ed. Stephen Cope (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007).

3. January 15, 2011: Familiarity in my reading might be thought to introduce asymmetrical gender dynamics, male author daring to address female subject too intimately. Returning to the essay, I have struggled with this issue, but have decided to leave it as is. [February 24, 2011: After a month of further reflection, I have decided to change it. Yet, it is important to both our projects, our mutual investment in the politics of writing gender and sexual difference, that some trace of this genuine struggle be left, as a kind of imprimatura (distinct from imprimatur), an underlying base (as in painting) upon which the rest is set. Not a palimpsest, for I do not wish to erase it by adding another layer. Any address of politics in Rachel’s work must begin with intimacy. And it is curious, and significant, that I have been so concerned with exactly this question of how to relate the intimacy of our intellectual bond and her mentorship, both rather queer. — ek] The word “Rachel” need not be problematic [February 24, 2011: … but it is — ek]: my relationship with her — as writer, critic, thinker, creator — has always been mediated by queer intimacies and familiarities. Moreover those intimacies have been inflected by our mutual self-consciousness about the conflicting simultaneity of normative and queer tendencies of each of our gender roles. I have toyed with the idea of translating each instance into “RBD” — but that is too heavy-handed. [February 24, 2011: Alas, it is not. — ek] “This will not be my RBD Book,” I keep joking (protesting?) to myself. Yet, in some ways, it is, at least insofar as this essay develops a reading and a writing that nakedly sorts out my own poetics through a mentor’s work, a queer male writer looking toward a female and feminist precedent. When fitting, the names of others will remain as I know them — as intimates —, though most are public figures, writers and academics of note. These friends, in my day-to-day living rather than in my role as institutional reader, have influenced my reading and thinking about Rachel’s work, at this time.

4. January 17, 2011: When analyzing Kafka’s fictions, Deleuze and Guattari note that the Czech treats desire as a force tied to writing connecting the literary page to the social world and transforming the subject so that she can test boundaries, to pursue justice instead of the law: “Writing for Kafka, the primacy of writing, signifies only one thing: not a form of literature alone, the enunciation forms a unity with desire, beyond laws, states, regimes. Yet the enunciation always historical, political, and social. A micropolitics, a politics of desire that questions all situations.” See Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature (1975), trans. Dana Polan (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1986), 42. Later: “One’s goal is to transform what is still only a method (procédé) in the social field into a procedure as an infinite virtual movement that at the extreme invokes the machinic assemblage of the trial (process) as a reality that is on its way and already there. The whole of this operation is to be called a Process, one that is precisely interminable” (48; Deleuze and Guattari’s emphases). My theoretic understanding of process is an amalgam of process philosophy (à la Whitehead) and the assortment of thinkers and writers he influenced, Olson and Duncan and their poetic heirs as well as Deleuze and his philosophic ones.

5. Rachel Blau DuPlessis, Drafts 1–38, Toll (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2001), 248.

6. February 24, 2011: It is somewhat disingenuous to represent this decision not to actively pursue publication of my poetry as an autonomous one. As a tenure-line professor, RBD herself had experienced an institutional resistance to the writing of (feminist) poetry and, worse, (feminist) poetic essays. Though the case has not been as extreme with me, and though I had received encouragement before tenure from Lynne, Pierre, Don, and others to ignore the institutional hierarchy to pursue my “real work,” it is still difficult as an academic to wear two hats. And even though I now have tenure, my own unstable institution has rendered this safeguard to intellectual or creative (not just “academic”) freedom nearly meaningless by announcing a decision to “deactivate” five humanities programs, thereby eliminating the positions of many tenured faculty, some world-renowned and several recognized and awarded by the same university in recent years as “distinguished” teaching or research faculty. Often now I feel vulnerable, committed as I am to the teaching of poetry, of creative thinking and philosophy, of issues related to our common humanity. Poetry continues to be a dangerous business, though it offers little by way of a material social revolution: its practitioners are usually the ones who suffer the most danger.

7. DuPlessis, Blue Studios: Poetry and Its Cultural Work (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2006), 35.

8. Ibid., 195. The printed version of this same lecture on Oppen also includes a footnote where RBD explicitly notes the intersection of objectivism and projectivism: “This is the point — poems tracking the graph of thought — at which a ‘projective’ poetics as in Olson, Creeley, and, differently, Duncan and Blaser meet the ‘objectivist’ tendency” (273n10).

9. January 17, 2011: One-half of my book in progress on anarchism and modernism (tentatively titled Life, Love, and War) is devoted to a revaluation of the shifting anarchist politics underlying Duncan’s process poetics between 1945 and 1970. The other half deals with the anarchist pacifism of Patchen and Rukeyser, as read through a collection of concepts related to political or politicized visionary poetics.

10. Martin Heidegger, “The Origin of the Work of Art,” in Poetry, Language, Thought, trans. Albert Hofstadter (New York: Harper and Row, 1936), 39.

11. Alfred North Whitehead, Process and Reality: An Essay in Cosmology (1929), rev. ed. David Ray Griffin and Donald W. Sherburne (New York: The Free Press, 1978), 129; Whitehead’s emphases.

12. January 17, 2011: Oppen: “And actualness in prosody, it is the purpose of prosody and its achievement, the instant of meaning, the achievement of meaning and presence, the sequence of disclosure which comes from everywhere, life-styles, angers, rebellions — I am not apolitical, and it is possible to mock poetry, it is certainly possible to mock poetry just as there are times when one is sick of himself, but eventually, I think, there is no hope for us but in meaning” (“Statement on Poetics,” in Selected Prose, Daybooks, and Papers, 49; Oppen’s emphasis). Duncan: “The end of masterpieces … the beginning of testimony. Having their mastery obedient to the play of forms that makes a path between what is in the language and what is in their lives. In this light that has something to do with all flowering things together, a free association of living things then — for my longing moves beyond governments to a cooperation; that may have seeds of being in free verse or free thought, or in that other free association where Freud led me to remember their lives, admitting into the light of the acknowledged and then of meaning what had been sins and guilts, heresies, shames and wounds” (“Ideas of the Meaning of Form” (1961), in A Selected Prose, ed. Robert J. Bertholf [New York: New Directions, 1995], 24, Duncan’s ellipsis).

13. March 26, 2011: Heidegger’s question was first asked by Hölderlin, and it is a question concerned with the intersection of a romantic commitment with what the German poet had saw as the “destitute” condition of an emerging modernity that devalues romanticism. See Heidegger, “The Origin of the Work of Art,” 91–142.

14. DuPlessis, Blue Studios, 42.

15. DuPlessis, The Pink Guitar: Writing as Feminist Practice (1990; repr., Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2006), 71; DuPlessis’s emphases.

16. December 10, 2010: Careless readers often miss the fact that reterritorialization is inevitable in Deleuze and Guattari’s philosophy of nomadism and romance of deterritorialization. It can’t be more explicit than where they write in Anti-Oedipus (1972), “In short, there is no deterritorialization of the flows of schizophrenic desire that is not accompanied by global or local reterritorializations, reterritorializations that always reconstitute shores of representation. […] Our loves are complexes of deterritorialization and reterritorialization” (Anti-Oedipus, trans. Robert Hurley, Mark Seem, and Helen R. Lane [Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1983], 316).

17. George Oppen, New Collected Poems, ed. Michael Davidson (New York: New Directions, 2002), 180–81.

18. January 17, 2011: “[…] the sincerity of the I and the we, it is a tremendous drama, the things that common words say, the words “and” and “but” and “is” and “before” and “after.” Our true faith is said in the simple words, for we cannot escape them — for meaning is the instant of meaning — and this means that we write to find what we believe and what we do not believe […]” (Oppen, “Statement on Poetics,” 49).

19. January 25, 2011: Jeffrey tells me that the publishing world is now concerned that people are just accumulating e-books, like so many unheard MP3s, rather than reading them. Now, as a culture, we are increasingly engaged in an electronic version of hoarding. Perhaps it is just a less cumbersome and space-demanding version of the sort of hoarding I, and so many other “book lovers,” already are guilty of.

20. January 16, 2011: It turns out that Oppen would not have appreciated this thought about audacity. A curious note I just found in RBD’s selection of Oppen’s correspondence, this in a letter he happened to write her while drafting “Of Being Numerous” (October 4, 1965): “There’s nothing very complex, nothing requiring tremendous aesthetic argument: we need courage, not ‘audacity’ — Pound’s word — but plain courage. To say what it’s like out there … out here” (The Selected Letters of George Oppen, ed. Rachel Blau DuPlessis [Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1990], 122, ellipsis in original). His preferred term “courage” reminds me of Arendt’s adherence to the same word, as the basis of a politics founded on communication and individuals’ making and sharing a world. (See especially Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition, 2nd ed. [Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998]; Arendt, The Promise of Politics, ed. Jerome Kohn [New York: Schocken Books, 2005]). But I wonder if Oppen had too much faith in the fact that one simply has to report on conditions “out there”/“out here” to establish that common, communicative ground. I don’t know what RBD wrote him to prompt this response about courage, but I do know that Drafts exhibits less of an easy faith in the reportage or in the sense that one will ever be heard. Courage to speak must be matched with a boldness to make oneself heard, all while listening well to what’s to be said. As RBD notes in her early essay “Language Acquisition”: “What writes listens. Listening is one of the major social and intellectual skills necessary for signification” (The Pink Guitar, 100). Perhaps that’s what the gendered difference comes down to between audacity and courage: knowing that it’s more audacious for a writer to stop and listen, rather than continuing to assert herself. Funny, though, that, if we are to believe Oppen’s letter, RBD learned that lesson about audacity from Pound, not from Oppen himself.

In the end, such audacity is not to be confused with authority or authoritarianism. RBD has such a precarious relationship to authority, both seeking it and divesting herself of it. This ambivalence comes from gendered lessons about the extent to which one has a self to assert. For instance, note how she writes of H.D.’s palimpsest form, which anticipates her own practice in the Drafts she would begin to write in the same year this study was published: “Palimpsest may have suggest the metonymic chain, a series of tellings of something with no one ever having final dominance, an evocation of plurality and multiplicity, lack of finality. This suggests the porousness of H.D.’s style, its unauthoritarian, constantly exploratory quality, despite this firm appeal to a final truth, saved from the embarrassments of authority precisely by being perpetually hidden as well as being exactly different from what dominant culture offers” (DuPlessis, H.D.: The Career of That Struggle [Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986], 56). In Drafts that unauthoritarian stance would come in privileging listening, collecting or gathering. For the most part, authorial agency is limited to pointing. Just note how for one Draft she uses a sentence from Wlad Godzich to define authority as an instance of deixis, of pointing (in DuPlessis, Drafts 1–38, Toll, 219). That itself is a performance of listening, of pointing, to another authority to define the basis of one’s own authority in listening, in pointing.

But I suspect that Duncan was the greatest influence here, at least in terms of how he connected attention and listening to a kind of poetic audacity. He exhibits great anxiety about his own writing when he, the ever-chatty one, had been talking far too much, caught up in “my own goings-on, going-too-far,” at the cost of paying enough attention to others. A remarkable moment of self-consciousness about this tendency arises in The H.D. Book: “But I was talking — would I ever hear what she [H.D.] had to say?” (Duncan, The H.D. Book, ed. Michael Boughn and Victor Coleman [Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011], 266, 265; Duncan’s emphasis). A field poetics is premised on the prioritization of listening, even for Olson. But for Duncan — as for RBD — that listening is not just a means to connect with the day’s American idiom, but instead the means of connecting, fully, with one’s social context and the language itself so as to re-vision one’s self.

Then what

Is “listening”? The ear

imitates

another listening in its

inner labyrinth

— sound’s alembic —

here,

the equilibrations enter in.

(Duncan, “Everything Speaks to Me,” in “Ground Work Before the War” and “In the Dark” [1984 and 1988], ed. Robert J. Bertholf and James Maynard [New York: New Directions, 2006], 105.)

I discussed this poem in my dissertation, using it to signal what I called then Duncan’s “passive” or “passionate” subject-position as author. After I had shown her a draft of the chapter, RBD spoke to me about what I had done in my reading of the line and of the particular wonderfulness of Duncan’s phrase “sound’s alembic,” the alchemy wherein listening and attending to one’s world enables a kind of action, a creation of one’s self and one’s poem. A similar kind of audacious listening finds its way into her poem as a disappearing of her self to let the here be all the more present:

For disappearance is the subject

of whatever I do.

If not disappearance,

then what is here.

(DuPlessis, “Draft 19: Working Conditions,” in Drafts 1–38, Toll, 127)

21. Oppen, New Collected Poems, 163, 164, 165, 166.

22. See especially Alain Badiou, Ethics: An Essay on the Understanding of Evil (1993), trans. Peter Hallward (New York: Verso, 2001), and Badiou, Saint Paul: The Foundation of Universalism (1997), trans. Ray Brassier (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2003).

23. Oppen, New Collected Poems, 164.

24. See DuPlessis, “Draft 3: Of,” in Drafts 1–38, Toll, 19–23.

25. Oppen, New Collected Poems, 165.

26. DuPlessis, Drafts 1–38, Toll, 21.

27. January 17, 2011: Looking back now, “trying” seems to be the key word in this sentence. Not just in the sense of attempting, but also putting her self and language on trial. What I find fault with below is addressed later in Drafts, when — in her wandering and folding back on herself — RBD moves outside aestheticized commercialized zones. Indeed, looking ahead to where “Draft 3: Of” folds in the sequence of the poem, in the meditations in “Draft 22: Philadelphia Wireman” (Drafts 1–38, Toll, 141–44), she moves to consider the noncommercial outsider work of the artist known only by that moniker given in RBD’s title. Here, we find RBD really working out this idea of writing as opening a procedural and processual space. “Be in the OF / and MAKE deep spurts from depths of cursive scrimmage” (143; DuPlessis’s emphasis). This localized writing allows her not only to wonder about the identity of the mysterious artist (“WHO DID the work?” [142]), but also to think about the present-ness of those conditions informing and permitting any aesthetic work, including her own (“HERE. and HOW.” [143]). What is curious for me, in light of my argument below, though, is that in topically turning outside (through the Wireman, to outsider art), Drafts still treats this space of procedure, this field of working the language, as a space outside institutional definition. In actuality, not even the outsider artist is fully outside the museums, galleries, markets of the art world. Some knowledge usually inheres, and, as is the case with the local outsider artist I know best, personally, the one in the town where I now live, one can be connected to the artworld via a simple desire to be known and to recognize the fact that painting obscene, childlike pictures of animal-human hybrids may be a means of feeding oneself and getting dope — especially if petty bourgeois [sic] folks like myself keep buying them.

28. DuPlessis, Blue Studios, 48–69.

29. DuPlessis, Blue Studios, 10. The concept of “urrealism” is implicitly developed through three essays: “Lorine Niedecker, the Anonymous: Gender, Class, Genre, and Resistances”; “The Gendered Marvelous: Barbara Guest, Surrealism, and Feminist Reception”; and “‘Uncannily in the open’: In Light of Oppen” (139–205).

30. DuPlessis, Drafts 1–38, Toll, 119.

31. January 17, 2011: Duncan’s open series Passages grow out of derivations from others’ lines and texts (one denotation of the word passage), and become interminable routes (another denotation of passage) through which he journeys (still another, now signaling the route of passage in an intransitive verb) in the intersecting course of his individual life and the poetic tradition. As he writes in his introduction to Bending the Bow, where the series first appears, “Passages of a poem larger than the book in which they appear follow a sentence read out of Julian. I number the first to come one, but they belong to a series that extends in an area larger than my work in them. I enter the poem as I entered my own life, moving between an initiation and a terminus I cannot name” (Duncan, Bending the Bow [New York: New Directions, 1968], v). Elsewhere, he describes the series as an engagement of an idea of poetry “having no bounds, being out of bounds” (“March 6, 1970. Preface to a Reading of Passages 1–22,” MAPS 6 [1974]: 53).

32. DuPlessis, Blue Studios, 61.

33. January 17, 2011: While pursuing research on Rukeyser, I recently encountered an essay by RBD I had not known about, on cultural Jewishness and her poetics. Here, she speaks implicitly to the “Jewishness” of Drafts as owing to a sense of responsibility to the diaspora and to the Holocaust: “Recurrent motifs and materials in many of these works are: home, homelessness, and exile, the death and the dead linked to the living, political grief and passion, including an attempt to look at the many corpses of the twentieth century. There is also silence, speaking and crying out, the sayable, the ineffable or unsayable. In many of these poems I speak of the enormousness of the universe, and the enormities of what has happened in our milky corner of it. I feel, increasingly, as the work goes on, that I am being spoken through, almost as if I were single-handedly building into existence some of the works of the lost” (DuPlessis, “Midrashic Sensibilities: Secular Judaism and Radical Poetics (A personal essay in several chapters),” in Radical Poetics and Secular Jewish Culture, ed. Stephen Paul Miller and Daniel Morris [Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2010], 211).

What I find most compelling about her discussion of Jewishness in this essay, though, is RBD’s claim to have gravitated specifically toward the story of Jacob and the Angel as an allegory for the struggle attending her writing: “When one enters such a gigantic task as a long poem, it is difficult not to think of being called and of struggling with something large, multidimensional, and fundamentally unknowable by which you have been touched” (213). This complicated struggle, mixed with vocation and being “touched” by the unknowable, speaks to the core of a politicized ethics, a giving of one’s self over to what is foreign and unknowable, in the service of a human good and a human justice. Such an ethic is not just Jewish, of course. As RBD reminds us: “And it is not ‘the Jews’ / (though of course it’s the Jews), / but Jews as an iterated sign of this site” (“Draft 17: Unnamed,” in Drafts 1–38, Toll, 111). This ethical struggle may be iterated through a cultural Jewishness but it is also related to her feminism, as is clear in her landmark essay “For the Etruscans,” from decades earlier. What she notes there about the experimental essay form speaks just as well to her poetics in Drafts: “The work is metonymic (based on juxtaposition) and metaphoric (based on resemblance). It is at once analytic and associative, visceral and intellectual, law and body. The struggle with cultural hegemony, and the dilemmas of that struggle, are articulated in a voice that does not seek authority of tone or stasis of position but rather seeks to express the struggle in which it is immersed” (DuPlessis, The Pink Guitar, 13).

34. Theodor W. Adorno, “Cultural Criticism and Society” (1949, 1967), in Prisms, trans. Shierry Weber Nicholson and Samuel Weber (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1981), 31. December 10, 2010: RBD takes up “the stark curse” of “Adorno’s verse” in “Draft 28: Facing Pages” (Drafts 1–38, Toll, 184), and matches it to his strategy of finding resistance in writing anyway, despite the impossibility of fully realizing an effective political resistance through writing.

35. Adorno, “On Lyric Poetry and Society” (1957, 1958), in Notes to Literature: Volume 1, trans. Shierry Weber Nicholson (New York: Columbia University Press, 1991), 45.

37. January 17, 2011: Echoes of this passage can be heard in “Draft 29, Intellectual Autobiography,” a canto written for the tenth anniversary of beginning Drafts: “Propose a work, the work, a work of enormous dailiness, vagrant / responses inside the grief of a century” (Drafts 1–38, Toll, 186). In her notes for this poem, RBD indicates that she began writing Drafts in 1985 — the year of “Otherhow” — and not in the year that the first poem is dated. “I had been composing Drafts for ten years, for they began in early 1985” (Drafts 1–38, Toll, 275n). Significantly, the original lines from the essay “Otherhow” are transformed into a meditation on the poem’s relationship to grief and mourning in her appropriating them for this anniversary canto. As I discuss below, that grief has everything to do with the poem’s passionate nature, with what I value most in Drafts: its ethical revaluation of agency so as to refigure our language for and thinking about politics. It is telling that RBD did not come to, or at least did not announce, this understanding herself until she was well along — ten years — into the process of writing the poem. As poets, how can we be expected to fully recognize or even claim the struggles in which we are immersed, those struggles defining our work and of which our work is a living part?

38. DuPlessis, The Pink Guitar, 147; DuPlessis’s emphasis.

39. DuPlessis, Drafts 1–38, Toll, 120.

40. On the concept social philology, see DuPlessis, Genders, Races, and Religious Cultures in Modern American Poetry, 1908–1934 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 1–28.

41. December 10, 2010: “The reality of artworks testifies to the possibilities of the possible. The object of art’s longing, the reality of what is not, is metamorphosed in art as remembrance. In remembrance what is qua what was combines with the nonexisting because what was no longer is” (Adorno, Aesthetic Theory [1970], trans. and ed. Robert Hullot-Kentor [Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1997], 132).

42. December 10, 2010: “Truth content is not external to history but rather its crystallization in the works” (Adorno, Aesthetic Theory, 133).

43. See especially Jacques Rancière, The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible (2000), trans. Gabriel Rockhill (New York: Continuum, 2004); Rancière, Aesthetics and Its Discontents (2004), trans. Steven Cocoran (New York: Polity, 2009); and Rancière, Dissensus: On Politics and Aesthetics, trans. and ed. Steven Cocoran (New York: Continuum, 2010).