Monoculture beer no more

Other poetries from Ireland

Discussions of the Irish poetry avant-garde, or avant-garde poetry from Ireland, or avant-garde poetry produced in Ireland, tend to focus on a lineage that begins with the quartet of Samuel Beckett, Brian Coffey, Thomas MacGreevy, and Denis Devlin, before continuing with Michael Smith’s New Writers Press and Trevor Joyce, Randolph Healy, Maurice Scully, Billy Mills, and Catherine Walsh. Sometimes there are extensions to include younger poets like Aodán McCardle and James Cummins. These poets have consistently rejected, or vigorously questioned, aspects that have come to seem inevitable to poetry from Ireland. And apart from one or two cases, their work has not become widely accessible.

Through multiple extensions, this lineage is slowly bearing an increasing influence to new writing from Ireland, posing a significant challenge to the blueprint of the (let’s call it) Heaney School. Whether there’s value in the type of poetry that still dominates publication, awards, etc., is beside the point; so overwhelming has its influence been on the vast majority of what’s being written — and, crucially, expected to be written — in Ireland that it’s become an unhealthy monolith. Conscious opposition to it seems necessary in order to bring about a liberating distribution of poetic modes.

Key to this shift is a pluralism of approach, plenty of cross-breeding and a geographically-outward attitude. Most of the writers mentioned above have either lived or spent considerable amounts of time outside Ireland: Walsh and Mills have lived in Spain and England; Scully in Italy, Greece, and Africa. Though biographical fact alone does not guarantee an alternative approach to writing, it’s partly due to living through other languages that some of these poets have been able to question the inherent parochialism of the poetry propagated in Ireland. There’s little of the obsession with the idea of Ireland in their work, and while it may address the geography of the country or the poets’ specific connection to it, there appears little attempt to territorialise the poems.

A common characteristic is the rejection of regular narrative modes and what they may signify. In Catherine Walsh’s Optic Verve, A Commentary, in particular, standard approaches to reading and writing are interrogated, as is the nature and function of words:

Whose place was it? To say what is its name is not tantamount to saying I don’t know what it is. Naming is not a speculative art and not necessary, as many seem to assume, to actual comprehension. Understanding. Naming makes communicative interaction a lot less tedious and time consuming. A coded shorthand of the specific, necessary component of the everyday dialectic of our lives.[1]

Words, then, as shorthand, form their own identities, and do not necessarily stand for things. In Walsh’s work, we remain constantly aware of the complexity of linguistic structure and intention by the disorienting effect of fragmentation or hybrid language — she often uses text in English, Irish, and Spanish without translations or explanations, as well as imported symbols and typography. It questions systems of (re)presentation and apprehension, and insists on an alternative way of reading and writing as an element of political redirection. Walsh’s is also a body of work grounded in immediacy, which views improvisation as a critical element of composition.

While Walsh’s writing is radical in practice and scope (Optic Verve bleeds into her subsequent book, Astonished Birds)[2]it is also grounded in the physical and even the domestic. These modes aren’t always or necessarily mutually exclusive. Maurice Scully’s work, too, can often be seen to stand apart from the perceived difficulty that accompanies the avant-garde label in that it contains a level of musicality usually expected in the work of writers within the lyrical mainstream — which, in Scully’s case, seems to have to do as much with an innate ear as with the training the poet’s hearing receives as it attempts to process new and changing types and patterns of speech, tones, and accents.

To place an “avant-garde,” then, and a “mainstream” in perpetual opposition would be to miss some fascinating shifts within and between these two vaguely distinct modes. Writers, poets especially, are allocated into groups, factions, or movements largely for the relative irrelevance of categorizing them in literary history books. Vital to recognizing new tendencies in poetry is a dynamic exploration that allows for cross-fertilization between practices. Up to now there have been very few continuous outlets for the exploration of radically different poetics and the spaces and dialogues between them emanating from or focusing on writing in Ireland. Journals and magazines largely fall into the trap of selecting from a narrow band of material, without making much effort to actively seek out or engender work that raises questions or drives a discussion — with a general lack of understanding of the editor’s role as instigator of new ideas and directions the main reason for this.

*

ask

(aloud)

what

is the font

of that voice?

(Kit Fryatt, “Why I Am Not a Performance Poet”)[3]

It’s fallen to the many spoken word and performance poetry initiatives which have sprung up, particularly in Dublin, over the past five to ten years, to bring about a widening of the perception of how poetry can be written and received. Poets who make innovative use of sound and movement energize language. Their power derives from the ability to communicate with audiences immediately. They can break through barriers of all kinds. And they make use of poetry’s earliest and most basic tools: the voice and the body. Their work benefits from the immediacy and vividness of hip-hop culture — a form of expression that has gained exponential popularity in Ireland — just as it can be limited by some of its more clichéd aspects.

One criticism of performance poetry everywhere is that it suffers from an anti-intellectualist attitude, which leaves the work rooted in the safe realm of the populist. Another is that it places too much emphasis on identity writing with an over-reliance on flourish or a clearly defined, easy-to-follow narrative. Essentially, on manipulating its audience into assent. These are fair criticisms to extend to the Irish spoken word scene. In general, an easily identifiable agenda surrounds the performance poem in Ireland. It brooks no uncertainties regarding its ideological position. In its eagerness to become understood and accepted at once, it eschews nonlinearity or complexity and aims to flatten experience into a series of cause and effect connections. A sense of interrogation taking place in the process of composition is lost through its collapse into a single dimension.

Like everywhere else, the Dublin spoken word scene has its exceptions. Tongue Box is a monthly reading series that has been running for several years in the Smithfield area (though at the time of writing it appears to be dormant). Presented by Raven and Cah-44 — whose collaborative performances of Cah-44’s sound poem “Dublin Onion” became, briefly, something of a scene emblem — the series is characterized by its hosts’ commitment to putting on an entertaining show with poets, artists, and musicians who are witty, energetic, and deadly serious about what they do. As with most such regular events, the quality on offer can be uneven between or within shows, but audiences rarely witness an indifferent performance. Occasionally, relative unknown or visiting poets and artists performing in collaboration will electrify the stage. And there’s an ongoing interest in alternative methods of dissemination, with poets encouraged to present in the medium that serves the work best — which is often anything but paper.

And if anti-intellectualism infects the generic performance poem, Kit Fryatt’s live work offers something of a remedy. Experimenting with personas, translations, updates of medieval lyrics, visual accompaniments, dramatic interpretations, and other devices, Fryatt’s performances seldom provide a single frame of reference. Her multifarious interests and activities as poet, performer, writer, critic, academic, editor, publisher, and much else allow her a range that bestows her work a complex cultural meshwork. Entertainment comes shrouded in mystery and ambivalence, in uncertainties and depreciations, and an intellectual intensity that forms the backbone of her practice.

*

With concrete or visual, sound, and, especially, forms of poetry that make use of conceptual writing strategies having remained stubbornly rare in Ireland, it’s mystifying how little attention has been paid to poets who have at one time or another adopted them. Evidence that, when prompted, writers here would be keen to engage more with experimental writing processes was seen during the UpStart collective’s poster campaign in the run-up to the February 2011 general election. Many of the text-based material erected then among the party political posters were clear examples of concrete or conceptual poetry. Context and medium were crucial; these were understood, by their authors and readers/viewers, as forms of slogans, with questions of politics, protest, public art, and temporariness vital to their acceptance as poetry.

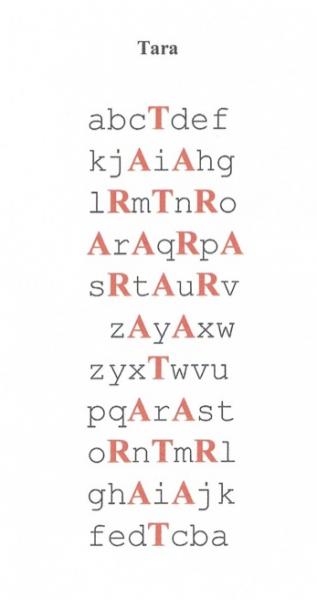

As far as traditional publishing goes, Susan Connolly is one notable poet to have used the visual form consistently. Throughout The Sun-Artist[4]and in the second half of her previous book Forest Music,[5] the presentation of texts (or “pattern poems,” as Connolly calls them) referring to the landscapes and history of the town of Drogheda in starkly visual terms offers a fusion of the traditional and the avant-garde — a fascinating positioning of lyrical or sentimental content within experimental writing practices. The fact that instances of concrete poetry, in some cases typographical word- or text-art, have as their subject something steeped in Irish tradition renders them strange, almost grotesque. This aspect of Connolly’s work is extraordinary in its rarity among recent writing from Ireland. Discussions of it have been muted within Ireland, with criticism of the work left to reviewers based in Britain.

Susan Connolly, “Tara.”

Anamaría Crowe Serrano’s One Columbus Leap offers a hybrid of formal experimentation, language deconstruction, and political investigation. It reimagines the gestation of Christopher Columbus’s journey from Palos de la Frontera in 1492 to the New World and follows it to its conclusion and beyond, displaying an innovative use of language and an acute understanding of its function. It employs several tools including prose, lists, and typography. The extract below is taken from the section “27 Leagues due West, September 15, 1492.”

The sea can be calm flat rough choppy sparkling and infinitesimal shades of the spectrum. A spectacle of poisoned ink, marco polo murk, mercurial, uncatalogued voyage green and brittle, middle kingdom blue, buddah, tang, ming and warrior glaze, maille grey silver pearl and dashed hope celadon, crackle mutiny ash and fortress slate.

The sea. Favourable. Spectered. Quadrant algae-rhythm underhue. Astrolabe and sextant turf, welkin samphire cirrus winds. Auspicious, haruspicious and benevolent.[6]

One Columbus Leap was published by the Paris-born and now Luxembourg-based Corrupt Press, run by Dylan Harris — who while living in Dublin attempted, in partnership with Kit Fryatt, to vitalize the scene with a series of readings they dubbed Wurm im Apfel. Through their events, including the Wurmfest weekend festival in December 2009, they introduced poets such as Jaap Blonk and derek beaulieu to Dublin audiences. Since Harris left Dublin in 2010, Wurm im Apfel has been run solely by Fryatt. Harris’s book antwerp contains a poem — part of which was erected as a poster in Dublin’s Dawson Street during the UpStart campaign — that articulates concisely much of what’s being discussed here.

ierland is geen belgië

(i)

body bag bread

monoculture beer

organic routes

malicious utilities

civilian trap

horseless guards

neighbourhood fear

armoured islands

easy talk

uncommon games

(ii)

the problem is it’s just one colour

now the colour is fine as a colour

but you might just stare at the black all night

and wish for the evening’s amber dawn[7]

Multilingualism and cosmopolitanism are strong features of Harris’s work; in antwerp there are poems “set” in Ireland, England, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Germany. He writes in “new city”: “gotta stop / being English // Engels.” The chapbook that preceded it, also from Wurm Press, is titled europe.[8] Harris has lived around the continent and views both place and language through the illuminative lens of a serial explorer. Rarely, though, does place come before language. And he is comfortable across forms: he has published work that fuses poetry and photography, while his interest in computer programming bears an influence. An advocate of the Creative Commons, Harris seeks through his work as publisher of Corrupt Press to promote work in English from poets whose first language isn’t English or who live in non-Anglophone territories, aware of the aesthetic and conceptual richness that may result through approaching language or cultural entitlement at a slant. It’s a wonder this idea, championed by Beckett among many, still seems such a novelty.

*

an impositional narrative

what other kind

exists

(Catherine Walsh, Optic Verve, A Commentary)

When networks of poets, publishers, editors, and critics start to resemble ghettos or exclusive clubs, then it’s time for a shakeup. Past experience suggests those operating in the margins who come to the attention of the mainstream are not before long lured into its workings. That the conditions for the emergence of a self-sustaining alternative, or for the growth of an ideology that resists such dichotomies, just don’t exist. In a poetry world as small as Ireland’s this has perhaps been especially the case. It’s an environment that presents those whose writing starts to outgrow the conditions that spawned it, but who don’t wish to compromise their practices, with a problem. Some of the most innovative writers are fleeing the country’s confined spaces, whether in intellectual or physical terms, to a large extent because of what they perceive as a lack of urgency in shifting this state of affairs. Not just a recent phenomenon, of course, but nevertheless worth remarking on after the huge wave of migration into Ireland over the past twenty years.

This is not unconnected from a sense of hierarchy that continues to dominate a general understanding of poetry as well as other aspects of public life — though outside influences and a new eagerness to question orthodoxies are beginning to throw things off course. It’s not a coincidence that most of the poets leading this change have minds and bodies present in more than one territory. The monoculture that brews poems arranged in neat lines and depicting closed systems, with their anecdotal, moralistic, sentimental, inward- or backward-looking tendencies, their preoccupations with homely things and things of home, their repeated use of specific metaphors and particular words — this monoculture is no longer sustainable. I’d argue that in these unstable, highly political, nationalism-infused times, it’s also rather dangerous. Just repatriating some kind of native perception into poetry is not enough; it cannot be expected to be of relevance or interest in the long run.

Driven by a few committed individuals, there begins to emerge a vital and disparate counter-scene that takes its tune from a newly honed political restlessness. Increasingly, writers who have entered the workings of “Irish poetry” from elsewhere are making their mark with hard-to-ignore activities and statements, while boundaries between poetic practices, genres, interests, and art forms are being — slowly — erased. Political writing does not only take the form of spoken word anthems or performance pieces looking for consensus. Despite much work that still relies on a traditional understanding of what a poem is or how it may come about, with a reluctance to experiment with processes and interrogate forms as well as the minutiae of language and how it’s employed persisting, a stirring has begun.

1. Catherine Walsh, Optic Verve: A Commentary (Exeter: Shearsman, 2009), 23.

2. Walsh, Astonished Birds: Cara, Jane, Bob and James (Limerick: HardPressed Poetry, 2012).

3. Kit Fryatt, Rain Down Can (Bristol: Shearsman Books, 2012).

4. Susan Connolly, The Sun-Artist: A Book of Pattern Poems (Bristol: Shearsman Books, 2013).

5. Connolly, Forest Music (Exeter: Shearsman Books, 2009).

6. Anamaría Crowe Serrano, One Columbus Leap (Paris: Corrupt Press, 2011).

7. Dylan Harris, Antwerp (Dublin: Wurm Press, 2009), 56–57.

8. Harris, europe (Dublin: Wurm Press, 2008).