'Maybe, it is only on Earth / that we lose the body?'

Williams and the decaying body

The most compelling feature of William Carlos Williams’s poetry, for me, has perhaps always been the complex tango of virility and fragility that fight it out in his deeply autobiographical poetry. The idea that man could be both potent and capable of great frailty was a fact of his work that resonated with the vigorous and clumsy youth I was when I first encountered his work. Williams traces the deterioration and ultimate betrayals of his body in his poetry, reflecting on both the particularities of his condition and the universals of aging. Despite his best attempts, Williams’s body would always betray his impermanence, and developing medical technologies only seemed to solidify his sense of its precarity.

Williams was always a bodily poet — think of his famous celebration of “my arms, my face / my shoulders, flanks, buttocks” as he “dance[s] naked, grotesquely / before my mirror” in “Danse Russe” from Al Que Quiere! (1917). But late in his career, he very deliberately engaged with a poetics of the body and wrote through dozens of attempts that paralleled changes to his body that would eventually end his life.[1] In some work, he maps a body onto the landscape; later,he traces a poetic genealogy of successors including Allen Ginsberg. In other work, he explores his own deterioration through the metaphor of the A-bomb and through the disorienting effects of his mother’s senility.

As Williams aged, he attempted to redefine the bounds of his own skin through his poetry seemingly in order to reconcile himself to his own decay as well as to reflect on continued anxieties about poetic immortality. He enacted the anxieties inherent to creative types, hoping that as his body weakened around his still-sharp mind that he could somehow guarantee the gesture of immortality, even as he acknowledged the necessity of grounding himself in reality.

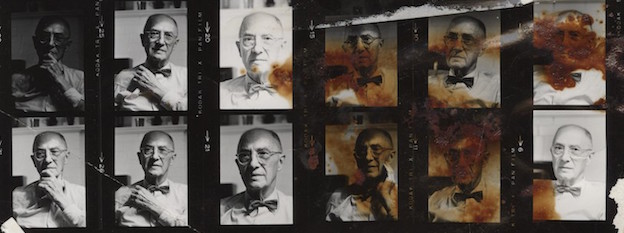

Williams 1961, Beinecke Library Special Collections (photographer unknown).

Williams engages in the language of medicine in order to establish narratives of a nonnormative body that is crippled by the traumas of time but persists: mapping his body outward onto permanent or powerful objects and spaces. In Paterson, his five-part epic-length meditation on both the titular city and the challenges and pitfalls of even attempting representation, Williams draws a parallel to his own late-in-life deterioration after suffering a series of strokes beginning in March 1951, creating a narrative of semipermanence set in stone and greenery.[2] Paterson the city becomes Paterson the man, who is as vast as he is unaging:

Paterson lies in the valley under the Passaic Falls

its spent waters forming the outline of his back. He

lies on his right side, head near the thunder

of the waters filling his dreams! Eternally asleep,

his dreams walk about the city where he persists

incognito. Butterflies settle on his stone ear.

Immortal he neither moves nor rouses and is seldom

seen, though he breathes and the subtleties of his machinations

drawing their substance from the noise of the pouring river

animate a thousand automations.[3]

That this city, who is also a man — “only one man –– like a city” — could be a stand-in for the poet himself, we need not think of Williams bombastically comparing himself to the bustle and thrum of the then-still-thriving New Jersey industrial hub. Instead, the poem invites us to reflect on the urgency of that man-city’s permanence in juxtaposition to, and in harmony with, the immortality of nature itself.

The hum of the Great Falls, slowing wearing their way through the face of the Passaic basalt, was as inevitable as Williams’s own fading strength, but his obsession with the consequences of such inevitabilities preceded the strokes that began in the early 1950s and eventually ended his life. Williams the Doctor-Poet was particularly suited to engaging with the medical language that became a predominant theme in his post-stroke poetry. He was more aware than most of the process of erosion to which his body had subjected him. Late in life, Williams would note that his medical training had influenced his poetry through its emphasis on precision of description.[4] Williams the Doctor allowed Williams the Poet new avenues of revelation regarding the blood vessels gone rogue in his skull.

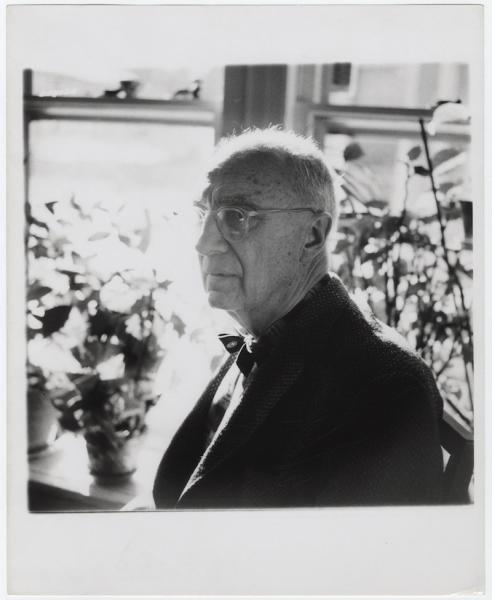

Williams’s business card, date unknown, the Poetry Collection, University at Buffalo.

And though he lived into old age through years of incredible medical advancement, the rapid growth of medical knowledge and practice also served to proliferate new anxieties about the body to which Williams, too, seems victim. The poetry that is most relevant to pursuing questions of embodiment and aging comes late in Williams’s career. But it isn’t his own old age that initially set him on a poetic search for immortality. Instead, I find the heart of his concern with personal decay appears in the poems reflecting upon the death of his mother Elena.

Elena, Williams’s Puerto Rican mother, lived into the beginnings of her son’s own old age, dying somewhere between the ages of ninety-eight and 102 depending on the source consulted.[5] The elder Mrs. Williams had a somewhat strained relationship with her son, though she had become increasingly dependent on him as she became more frail, finally sinking into senility, at which point she was placed in a nursing home by her son in order to make room for his brother’s family in the house they had shared.[6] Years before her death, Williams first acknowledged the weakness of her body in “Eve,” calling it her “wasted carcass” and noting her unwillingness to slip dignified into death in a manner that would best suit her son: “One would think / you would be reconciled with Time / instead of clawing at Him / that way, terrified.”[7] But it is not Elena’s body that most troubles Williams, but the ways that her senility shakes his own sense of self. Particularly jarring is the identity crisis begun in “Two Pendants: For the Ears” where the dying Elena fails to recognize Williams:

Elena is dying.

In her delirium she said

a terrible thing:

Who are you? NOW!

I, I, I, I stammered. I

am your son.[8]

The stutter of shock and discomfort — the “I, I, I, I” — that he produces in identifying himself to her when she does not know him makes tangible his surprise at finding their lifelong connection suddenly unmoored by the tricks of her ailing mind and body. For Williams, aging and failures of memory are inherently tied to a sense of self. The poet’s sense of self can only for a poet be expressed by speech. In losing her mind (so to speak), Elena has lost not just her history but also somehow lost Williams for himself. His stammering “I, I, I, I,” grasping at his suddenly porous identity. It is this misrecognition that sets him on his path toward reconciling his mortal body with a world of language that would outlast him.

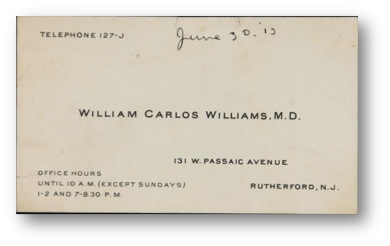

Williams and Elena Williams, his mother, sometime in the 1940s, Beinecke Special Collections (photographer unknown).

Two years after Elena’s death, William’s own march toward the grave would begin. One of the most debilitating results of the strokes that plagued Williams for the last decade of his life was the sudden loss of speech and motor-skills which greatly diminished his ability to write and type. It is no surprise, then, that “Asphodel, That Greeny Flower,” begun around the period of his first stroke and published in 1955, reflects a sense of helplessness when faced with the bombs that were going off in his brain. Though its primary message is one of apology toward his much-betrayed wife, Flossie, “Asphodel” is frequently concerned with the failure of the body to form the words that the mind imagines and the stakes of such failures in light of impending mortality. The only escape from the power of the bomb is imagination, which makes men immortal, unless they are silenced by their own bodily betrayals. Ultimately, “The bomb speaks” and man is unable to find the language for an appropriate response so “We come to our deaths / in silence.”

Williams’s poem is evocative not only because of its vivid depiction of interior decay, but also because his decay occurs in tandem with the technological advancement and destructive potential that defined the nuclear age. Radioactivity, and the resulting “radiant gist” that had haunted the work of Paterson Book IV after he watched Mervyn LeRoy’s schmaltzy 1943 biopic Madame Curie, both allowed for the revelatory treatment possibilities of the x-ray and for the destructive force of the A-bomb.

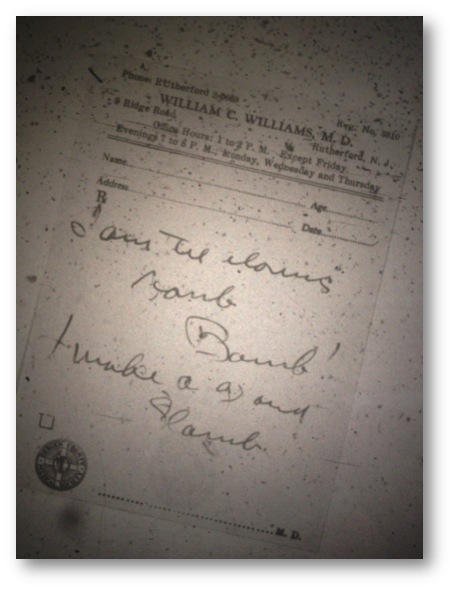

Notes on a prescription pad from the early drafts of Paterson, including an idea Williams would later develop in “Asphodel, That Greeny Flower,” ca. 1948, the Poetry Collection, University at Buffalo.

But the connection that Williams makes between his strokes and the bombs is not so straightforwardly related to their shared destructiveness. Instead, we are asked to understand the bomb in relation to the flower. The unappreciative living ignore the asphodel, a lowly weed, while the dead look to it and wonder, “What do I remember / that was shaped / as this thing is shaped?” An asphodel shares its silhouette with a mushroom cloud, reiterating the themes of mass-scale destruction as well as the connection Williams draws between destruction and creativity.

In finding a parallel between the asphodel and the bomb, Williams finds a logic for the micro-bombs in his skull. Curie’s search for what Williams termed the “radiant gist” in tons of pitchblende represented for him the potential for beauty and worth in dreck and heartache. Though it is too neat to read the claims in “Asphodel” for a rebirth resulting from the bomb, when Williams says, “In the huge gap / between the flash / and the thunderstroke / spring has come in / or a deep snow fallen. / Call it old age,” there does seem to be an acknowledgement of a utopian potential to aging. Certainly Williams has experienced a sea change. It remains undecided whether the new version of himself that he must grapple with is irreparably damaged — is he now that “wasted carcass” he had pitied only a few years before? — or if there are glimmers of a Williams as-of-yet-unexplored. But there is a possibility that Williams now, like the dead before him, has come close enough to the threshold of another world to now appreciate the asphodel, which “has no odor / save to the imagination / but it too / celebrates the light.”[9] “Give me time, / time,” he had implored, time to make tangible and articulate his flooding memories early in “Asphodel.”[10] Now he knows that he needs time only in order to “refuse death” and to keep “the light” of his mind out of death’s reach.[11]

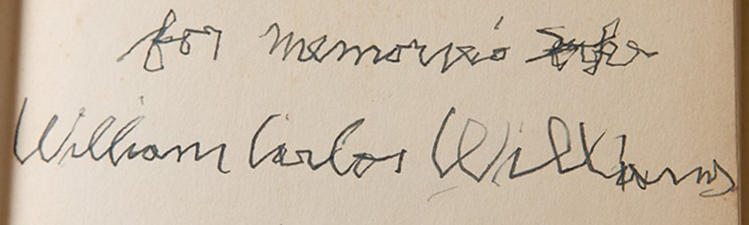

Williams’s shaky handwritten 1955 inscription to Charles Abbott in a 1951 copy of his autobiography, the Poetry Collection, University at Buffalo.

But Williams was nonetheless aware of the betrayals a body could make to a still-sharp mind after months of fighting to recover his speech, handwriting, and typewriting skills.[12] In his translations of three Nahuatl poems, first appearing in The Muse in Mexico of 1959, Williams places key emphasis on the phenomenological experience of inhabiting a body. This emphasis is particularly clear when you compare these versions to John Bierhorst’s controversial translations. While Williams translates the lines as: “Or, maybe, it is only on Earth / that we lose the body?” Bierhorst translates them as: “The place where all are shorn is here — on earth!”[13] Bierhorst parses this song, like “Asphodel,” as representative of the desire for immortal life, though in this case the figures more closely resemble the walking dead than wildflowers.[14] Certainly, Williams’s translations are more beautiful, more simple, but they also shed light onto the primacy that Williams placed on the experience of living itself and the ways that being trapped within his own slowly dying body became central to his poetic sensibilities, even as he lost the ability to speak and eventually lost some of his hold on language itself.

The readings that I have been able to link to here from the archives of PennSound are all recordings from the last fifteen years of Williams’s life, and they reveal, I think, that despite his deterioration and despite his struggles to relearn the basic motor-skills required to continue writing, Williams remained vital. This was no husk. He read with excitement, delivering lines that sent his audiences tittering and offering applause of admiration, not pity.

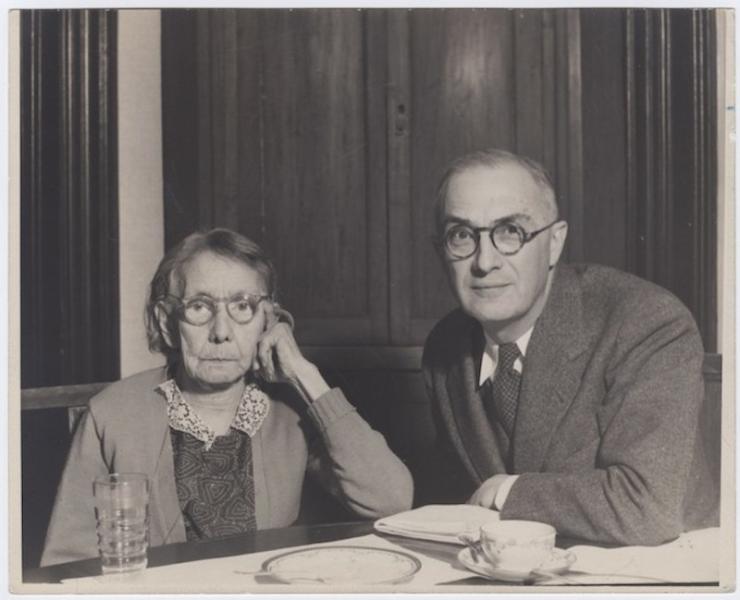

Williams and his wife Flossie taken sometime in the 1950s, Beinecke Special Collections (photographer unknown).

Williams ceased his public readings after his third stroke in 1958 and continued to suffer a series of smaller strokes, or transient ischemic attacks, until his death in spring 1963.[15] His biographers have already traced the impact this had on the poet emotionally, and though he spent much of these last five years depressed by his struggle even to speak, an interview with Stanley Koehler for The Paris Review from eleven months before his death reveals his continued investment in conveying the particularities of his bodily experience.[16] He insists he cannot speak in a clear and sharp voice, perseverating on the damage wrought by the strokes. He is plagued. His voice hesitates and quavers, but Williams remains. Koehler remarks upon the opening lines of the fifth and final book of Paterson published two years before: “In old age / the mind / casts off / rebelliously / an eagle / from its crag.” But Koehler does not quote the lines that follow: “— the angle of a forehead / or far less / makes him remember what he thought / he had forgot // — remember confidently / only for a moment, only for a fleeting moment / with a smile of recognition.”[17] It is these lines that, in some ways, seem a most fitting epitaph for Williams. Growing old was hell. But in old age there was a clarity that had not been available to the virile young Williams admiring his naked flesh in front of the mirror in the north room. Ending his interview with Koehler, Flossie, who has joined them to facilitate conversation, is listing the translations of Williams’s works. Williams, triumphant, shouts, “I’m still alive!” Perhaps this is the memory the old man catches hold of in Paterson. “I’m still alive!”

1. William Carlos Williams, The Collected Poems of William Carlos Williams, Vol. 1: 1909–1939, 86–87. Williams was in his mid-thirties when he wrote “Danse Russe.”

2. Paul Mariani, William Carlos Williams: A New World Naked (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1990), 629–30.

3. Williams, Paterson (Book I) (1946), 6–7.

4. From an interview in The Paris Review discussed at further length below.

5. Biographer Herbert Leibowitz says 102, while Mariani, generally the preferred biographer (likely due to his status as the only biographer for more than twenty years), cites no specific age.

6. In his Williams biography, “Something Urgent I Have to Say to You”: The Life and Work of William Carlos Williams (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011), Leibowitz quotes Williams’s dying father as saying, “The one thing I regret in going is that I have to leave her to you. You’ll find her difficult” (51). The moment shared between father and son certainly seems telling of the relationship between mother and son.

7. Williams, The Collected Poems of William Carlos Williams, Vol. 1, 413.

8. Williams, The Collected Poems of William Carlos Williams, Vol. 2, 211.

10. Williams, The Collected Poems of William Carlos Williams, Vol. 2, 312.

12. Leibowitz, “Something Urgent I Have to Say to You,” 405.

13. Before Bierhorst’s translation in 1985, the Cantares Mexicanos had never been translated in their entirety into English and had been popularly thought to be the core text available to scholars of pre-conquest Aztec life and literature. In his “General Introduction,” Bierhorst made the claim that these songs were actually largely post-conquest and heavily influenced, even possibly entirely invented, by the invading Spanish. Chicano scholars have since largely dismissed this component of Bierhorst’s work, while his translations remain acclaimed.

14. Cantares Mexicanos, trans. John Bierhorst (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press), 249.

15. Leibowitz, “Something Urgent I Have to Say to You,” 435.

16. Stanley Koehler and William Carlos Williams, “William Carlos Williams: The Art of Poetry, No. 6,” The Paris Review no. 32 (Summer–Fall, 1964).