Ídolos among us

The innovative aesthetics of contemporary US Latinx poets

Ni de aquí, ni de allá: The US Latinx poet as overlooked

Yo busco nuestra gente en las luces brillosas de un Google Search. Encuentro luminaries like Julia Álvarez, Isabel Allende, y Esmeralda Santiago. Más chingonxs surface on the screen: García Márquez, Neruda. But as I keep scrolling, it dawns on me that almost all are either fiction authors or from the Latin American continent. Their works are written in a language most of us learned orally from our parents, that we stumbled through in parties and visiting relatives. I go on to read the links. Each article rehashes a list of the must-read writers of the moment: Huffington Post’s “23 Books By Latinos that Might Just Change Your Life,” Remezcla’s “5 Books by Latino Writers You Should Read in 2018,” or Latina’s “Our Favorite Latino Authors.” I keep searching, trying to find our canonical voices as “US Latinx Poets.”

Where are our roots?

This designation may come off as quibbling with semantics. Consider, though, that our people comprise 57.5 million, or approximately 18 percent, of the country’s total population — and that figure from the government census is already two years old.[1] Toward the bottom of the window, I reach the Library of Congress’s “Spotlight on US Hispanic Writers” (their words, not mine). I pause and smile at the warm faces I’ve grown to call my mentors and contemporaries: Francisco Aragón, Javier Zamora, Laurie Ann Guerrero, Rigoberto González (my beloved teacher while I was an MFA student at Rutgers-Newark), and several others. And it is this elation of seeing my literary parientes that reminds me of the greatest solace of being a Latinx poet right now: everyone I admire is still alive.

Whereas the Black literary tradition may harken back to the Harlem Renaissance, the antebellum writings of Phillis Wheatley and Charles Chesnutt, and even the slave narratives of Frederick Douglass and Harriet Jacobs that adorn every classroom in America, our literary tradition is much more recent. To be fair, Americanist scholars within the past ten years have nuanced the very argument I am making. Raúl Coronado’s A World Not to Come unearths the forgotten writings of José Antonio Gutierrez de Lara, Jose Álvarez de Toledo, and other escritores of nineteenth-century America.[2] Moreover, let’s not continue to erase the Afro-Latinx heritage and the interventions of towering figures like Arturo Schomburg, the Puerto Rican intellectual who is the namesake for the Center for Black Culture in Harlem. My claim’s focus, though, isn’t historical, but rather interrogates the American literary imagination. It bluntly asks: besides Cisneros and Soto, who are Latinx poets readily conjured in our students’ minds, let alone in the general American public’s?

Latinx Poetry, y el problema of Mexican hegemony

And sure, I’ve neglected to mention other key artistic movements of Latinx poetry. There is for instance the Chicano Literary Renaissance of the 1960s, which ushered leyendas like Lorna Dee Cervantes and Juan Felipe Herrera. Note however that even with these caveats, the dominance of writers of Mexican descent persists in our lineage. There is a subtle violence in this. Imagine the aspiring Salvi (Salvadorian) or Chapina (Guatemalan woman), scouring the library shelves for collections with an accent in the book’s spine — with a last name like theirs — only to feel, upon opening our collections, out of the loop once more. Chew on the fact that all their lives, they’ve had to wrestle with our hegemony.

My querido profe makes no bones about this issue. In the introduction to the acclaimed anthology, Camino del Sol, and addressing the fact that twenty-five out of the thirty-seven selected authors in the book self-described as Chicano/a, he wrote, “I’d like to celebrate the continued presence and perseverance of Chicano/a writers whose politicized identity prevails despite the erasure imposed by the label, “Latino.”[3] His reply amounts to saying, “Well, we pull more weight [than other nationalities].” And with all due respect for my teacher, I have to ask (him), isn’t that a bit of a circular argument? Again, when non-Mexican lenguas have to live off our institutional memory, our cultural images and artifacts, our idiomatic expressions y dichos y formas de pensar, aren’t we reenacting this imposing? And for the sake of aesthetic diversity and innovation, I believe we should be wary of unconditionally lauding our “perseverance” since it might overlook the kind of coercive practices we might inflict on our peers.

Pochx poetics: Two poetas making this language ours

But the beauty of our genre is arguably the tenacity of its most ostensibly marginalized members. As Jesse Lichtenstein in her Atlantic article, “How Poetry Came to Matter Again,” poignantly put it, “If anything, the current crop of emerging poets anticipates the face of young America 30 years from now.” And for Latinx poets, this is especially true. Our pages están hechas a mano. Ain’t no receta for the majority of us on the come up. Instead, we cull every corner of our (family’s) newfound home that is los estados unidos (or “el norte”). We scour the Costco shelves of American landscape, claiming each object — the shopping malls, Saturday-morning cartoons, English itself — as lo nuestro. This is precisely what Cordero and Lozada-Oliva do: comb (an all too literal act in Lozada-Oliva’s case) through the multiple Englishes of immediate surroundings, filtering each register through their distinct poetics — in Cordero’s case, those of a Calexico-raised poet-archivist who documents the violence against Mexican (American) bodies in the twenty-first-century borderlands. Hers are not so much poems as they are inventories, filing through memory for the everyday items that spell our people’s survival. “Fideo de pollo,” “a flock of cilantro,” “guitar bones,” “corazones de stones,” and “goat heads” are just some of the stunning objects in esta ofrenda de un libro. In Lozada-Oliva’s work, she combs not the desert sand, but hair; that is, the Latina body as it entangles in the multiple frays of race, language, and sexuality. Her poems are often strophic, a shape which throws us back to the New York subway on a Friday evening, a crowd of sounds tumbling with registers that are so expansive and reaching that it feels as if she’s fit whole Americas on the page. After all, is not the image of mamás coaxing their hijas to wax their eyebrows a universal one, painfully familiar to those of us reared on the adage that we must look our best, for our best is all we have? Lozada-Oliva displays this intergenerational passing down of cultural values in real time as she writes, “Ow! / will win the pageant, melucha / Ay-Carajo-Shit! has a medal around her neck, / mi linda, Cómo Me Duele drives a shiny car / with the top down to the prettiest place / in the world, mi peluda”[4] These two books are in dialogue, one that is perhaps best captured by Lozada-Oliva herself, “Bikini lines become / bikini borders.”[5]

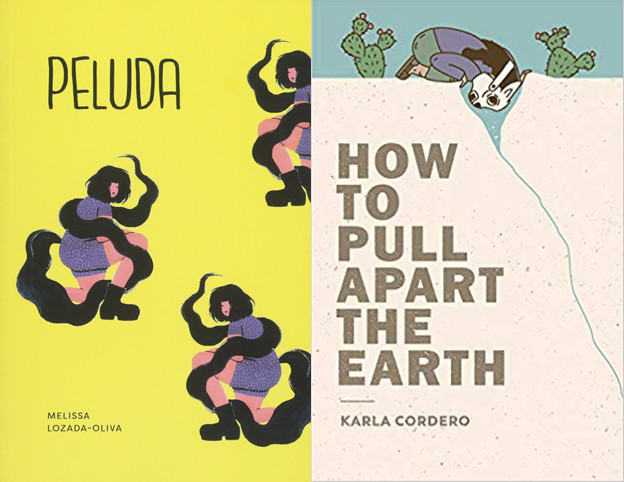

This review-essay examines the works of Karla Cordero’s How to Pull Apart the Earth and Melissa Lozada-Oliva’s Peluda. Written in the last few years, both works reinvigorate our tradition with deft risks in form, diction, and lineation. Their landscapes certainly pay homage to the pastoral hills of our migrant parents, yet they trespass (and transgress) into the globalized realms of the digital. Their feet planted in memory, but their thumbs in the touchscreen geographies of the American millennial. Naturally, their influences extend beyond the formally literary. They’re not just well-read, they’re hyperliterate. As my tía Carmelita would put it, “Hablan inglés, derecho y al revés.” Their lyrical modes borrow from the so-called magical realism of our parents’ literary tradition, but grounded within a US context. Consider Cordero’s poem, “Truths at the All-American Canal,” how lines like “a man slaughters a tree & gives birth / to a boat” drown out the chilling connotation a word like “slaughter” carries, words often conditioned by a US media obsessed with the pornography of war.[6] Instead, Cordero shores us to the strange yet sublime image of a migrant giving birth, how la mojada bears maternal qualities in her affirmation of life despite threats around her. Taking my point of departure from Lichtenstein’s prophecy, I’ll bet veinte pesos that voices like Cordero and Lozada-Oliva are the microcosm of our future: advocates against violence in many forms — from la frontera, to a nail salon’s chemicals. But beyond a reactive poetics, they architect, amidst their barrio bedlams, a radical brown joy.

“in Mexico 35 somebodies were crucible to sainthood”[7]

Don’t get it twisted. Cordero, the Chicana of the duo, is our generation’s Anzaldúa. I say this with no hyperbole. Hailing from the border town of Calimexico, it perhaps makes sense that her economy of language is one of compression. Her poetics are a throwback to the opening pages of Borderlands, where Anzaldúa wrote, “The US-Mexican border es una herida abierta where the Third World grates against the first and bleeds.”[8] But if the border is indeed an open wound, Cordero took our mother’s scab and stitched together a tapestry where Mexican/American skin and body are graphed onto the numerous landscapes of Latinx identity in the Southwest. That is, she removes us from the barbed politics of a proverbial Wall, the need to perpetually wire our lyric with a merciless desert. Just glance at the titles of her poems: “Nopal en El Frente,” “His Jawbone Caged my Grandfather’s Skin,” “Momma Knows all the Monsters’ Hidden Teeth,” “Abuela’s Hair.” All body, body, body, and body implicated in questions of language, agricultural labor, and the historic exploitation of the campesino, the domestic space and its attendant rearing of gender norms — the themes she unearths are limitless.

Stylistically, Cordero is building off our Latin American predecessors, thereby bridging our linguistic divide with a shared genre. She reclaims for us the novelistic scope of surrealism and under the pressure of noun and verb, melts the familiar faces of hurt. Take the piece “Abuela Is a Machete Wrapped in Her Favorite Apron.” Even in a prose poem, a hybrid style that disavows the line break, her tremendous care for language sustains an energy that affords the speaker’s social transcendence. Just listen to the chispas of the opening: “a man once slammed a fruit bowl against the kitchen wall,” an image ostensibly foregrounding domestic violence and doubly important for immigrant women; fears surrounding deportation often intimidate them from reporting their spouses to authorities.[9] As such, there is likely an underreporting of abuse, reflected in official statistics and pop culture.

But Cordero refuses to let machismo — or its campaign to mute these voices — rule the day. She follows with, “& / abuela learned how glass can birth small daggers.”[10] A novice poet would’ve replaced birth with “make,” “produce,” maybe even “wield.” But this diction is crucial. In fact, it’s political, nodding to the maternal, to the primordial ability for women to create amidst existential threats. Cordero throughout this collection revises the matrilineal to implicate a militant tradition (as we may also observe in Lozada-Oliva’s work). Perhaps this activism of older Latina generations is not dressed in the revolutionary aesthetics of, say, the leather jackets of the Black Panthers or Brown Beret. But nevertheless, these Latina forbearers’ strength is self-evident. Cordero continues, “She replaced / her husband with knives. holds a blade like a loaded gun.”[11] And so what is marvelous about Cordero’s work is its transcendence, how this armed resistance bleeds into the domestic in such a subtle and rich way that the two boundaries become indistinguishable. Revolution not in la plaza but in la cocina.

Take the next line, “enjoys / the chop of cilantro-bundles for caldo.”[12] In other words, the grandmother isn’t engaging in a physical fight per se. Her agency lies in an art of living that reminds the enemy, to put it bluntly, whom he’s fucking with. Here comes the next tumble, cued by the ampersand, which looks more and more like a metal spring, “& people swear she got / lawnmowers for fingers. in the backyard the trees shed fruit baskets / but abuela dislikes the rind. can scalp a pear’s skin in seconds. / clean. See the sugar bleed off the slice. each hand a steady butcher.”[13] There are so many moments where the reader is moved to stop, to marvel at the transubstantiations of a lawnmower for fingers, of these women.

Cordero accomplishes this precisely due to her organic vocabulary, which fruit-picks from the everyday objects of the Latinx working class. She alludes to the sentience of trees through diction which suggests a motif of skin, hence the word “shed.” Cordero then writes how this elder can “scalp a pear’s skin in seconds.” Cordero’s word choice not only layers this moment with surrealist imagery but situates its implications into a larger history of indigenous resistance. Recall the words of Anzaldúa, “I am a border woman. I grew up between two cultures, the Mexican (with a heavy Indian influence) and the Anglo (as a member of a colonized people in our own territory).”[14] With “scalp,” the page echoes with the ululations and battle cries of the former, how indigenous tribes such as the ones we descend from did not simply acquiesce to the colonial projects of Spain and the United States. They fought back.

Resisting a romantic salvation, Cordero whiplashes us to our sobering present. Preserving the poem’s metaphor of shards, Cordero writes, “then dr. gonzalez found her memory carved to pieces … the house keys chained to her apron & sometimes her mouth switchblades.”[15] Cordero “misplaces” verb and noun, a poetic forgetting that nicely parallels the grandmother’s own. Amidst a period of ostensible decline, our matriarch still awes us with a mouth that switchblades. She doesn’t “rescue” our grandmother; the latter wields whatever’s in her grasp. “She swears she’s always loved / the fruit’s pale flesh & her teeth a wooden drawer of machetes.”[16] Straddling the mutual temptations to redeem and reject, Cordero imagines a guerrilla domestic, one that enmeshes houseware with wrinkled arms. Y se los repitiré otra vez: our author could’ve chosen to end with “knives,” but the choice of machete is significant. It echoes of an elsewhere, of a Spanish-speaking land where campesinos sheath crop with teeth-like metal and metal-like teeth. To a peasantry who harvest life. To survive violence long enough to create — perhaps that is the poetics of both this Latinx poet and her (and our) grandmother.

For all of Cordero’s careful documentation of Mexican bodies as they traverse the various lines which promise both mobility and death, lines running through nation-states and kitchens, one wonders of the violences against us which don’t wield a knife. Do they still shape Latinx understandings of themselves in profound ways? Melissa Lozada-Oliva answers in the affirmative, holding in her hand the previously unexamined evidence of a wax strip.

“before there were legs, bikini lines, eyebrows / upper lips / underarms, forearms, labias, assholes, chins, or the waxing table there were houses / & two immigrants who cleaned them”[17]

These are the first words of Peluda, or should I say, its limbs. In her third chapbook, the Guatemalan Colombian Melissa Lozada-Oliva, siendo the badass priestess she is, remixes nothing short of a Latina Genesis. The title of this first poem, “Order Regimen,” suggests so. Line by line, the piece fleshes out the classed creation of Latinx bodies in the United States. But it’s far from Edenic. Referring to an unborn self, she writes, “you were there the whole time / in your mother’s belly, weighing her back down / with the heaviness of your life, inhaling fumes / from the windex & the bleach.”[18] We weren’t born into Adam and Eve’s world but a toxic “urbanlandia,” American inner cities whose chemicals slowly poisoned our mothers. Rodrigo Toscano’s poetics whispers in these poems. In particular I am thinking of works such as “At a Bus Stop en el Barrio,” whose first line reads, “Tha’ vahnahnah go-een to keel joo.” Once stigmatized as unintelligible or “broken English,” Toscano reappropriates the Latinx immigrant’s disorientation as one that pulsates with a performative quality. Throughout Peluda, Lozada-Oliva likewise interjects her own transliterations, the locale in question not a bus stop but the domestic sphere: “Joo need to heat up de wax.”[19] The effect of this language is twofold: an enriching of the poem’s texture on purely aesthetic terms. But more importantly, the poet’s voice, historically written as a male solitary figure, is disrupted and fractured by these migrant voices. To write in this manner, therefore, is a political act, an implicit declaration that our vernacular is as valuable, as artful, as any lexicon of the so-called learned.

Lozada-Oliva’s poetics rests in rendering the familiar uncanny. As fellow Macondista Gionni Ponce put it in her review, “Lozada-Oliva puts beauty regimens under a microscope. She describes hair left on pillowcases and strangers getting bikini waxes on the family dining room table in such extreme detail that our ideas of beauty become strange and disgusting to us.” To us. That’s a key qualifier, as both Cordero and Lozada-Oliva implicitly aim their words at a readership who is perhaps removed — in terms of gender, ethnicity, language or citizenship — to the issues they raise. Indeed, Lozada-Oliva’s technique amounts to what Ponce calls a “gurlesque aesthetic.” Again, I like my camarada’s phrasing, as it sonically echoes the word burlesque but rejects its historic catering to a male gaze. Rather, as the root suggests, “the gurlesque” enacts an internal dialogue between Latina women of all generations, tracing a lineage of transgression — in all its myriad forms. Hence the recurring “you” in Peluda, which at first blush strikes the reader as confessional. But upon revisiting, the “you” amplifies to an “us” that for too long has been invisible. “you love the black polish on your big toe,” she writes, “in the shape of a country you’ve never visited.”[20]

This couplet alone is a microcosm of Lozada-Oliva’s magic, her nimble two-step between brown girl love and her complex relationship with diaspora. Such themes are further accentuated in poems like the Ocean Vuong-inspired “I’m Sorry, I Thought You were Her Mother.” The speaker admits, “if you don’t understand the joke then perfecting / your American laugh if not catching / the reference then writing down to google it.”[21] Note the technological language in these opening lines as well as the heavy use of gerunds. Perfecting, catching, writing — these -ings are crucial, as they gesture at the task of the US Latinx that an infinitive verb embodies. At pains to assimilate by any means necessary, she lays low, says sí maestro as our parents once taught her, only for her accent to betray her Othered origin. She doesn’t exist in the positive sense of the term, instead defined by a litany of “no’s.” Not “beautiful” nor “pretty” nor “hermosa,” nor “muñeca,” she is instead like her father. Here is her first association, “i guess then juggling eggs & balancing your passport on your nose.”[22] In addition to these poignant questions of belonging, the consonance in “juggling eggs” reminds us that Lozada-Oliva, in these sixty pages of gyrating lines, hasn’t sacrificed craft for scope.

On this note, her form’s subversive as well, transgressing the convention of the clean line break. The stanzas can be unruly at times; many bear the imprints of spoken word pieces. In workshops, such a decision would be criticized as self-indulgent, or navel-gazing at the expense of the poem. But what tethers such a fast-paced collection is precisely this length, a recursive calling towards the body. Combing through poems like “Lip/Stain/Must/Ache” provides insight as to why such an approach is so successful. In this work, she queers stereotypical depictions of the female muse. She writes,

my ugly mustache distracts from the red lip

stain.[23]

Restless, the lines zigzag, searching for this a matrilineal alternative. In this journey, she subtly calls out the double standard a figure like Junot Díaz represents — how Latino men (of letters), in spite of their racialization, are able to possess alter egos who womanize but are safely laundered as an author’s license. She retorts, albeit in parentheses,

(do you have an alter ego, mami? […] does she kiss a lot of married men? Haveyou ever let her skirt fly up in the breeze?”[24]

The switch in perspective reveals a speaker at pains to normalize her sexuality, who while ostensibly heterosexual is deemed deviant by machista culture, a sin vergüenza. After this reimagining of her mother’s adolescence, the speaker returns to Junot: “he says red lipstick was made para las latinas / i am latina or I just like being watched by / men / or I just like leaving / marks on their shirts.”[25] That “or” is an important pivotal moment. Indeed, the long space itself symbolizes a coming-of-age declaration of one’s pleasures. It retorts to Diaz, his essentialist attribution of red lipstick as “a Latina thing.” It reclaims, in playful musings, this gaze as her agency.

Peluda once meant a pejorative for a hairy woman. With Lozada-Oliva’s collection, let us now call it a defiant break from the sexual policing Latinas have endured. Through its gurlesque dancing to and from scenes, this poet guides Latina readers toward reverence for their own bodies. Perhaps this is what Chicana Feminist Chela Sandoval meant when she coined “revolutionary love,” an emotive politics driven not to please the oppressor but to name (and rename) those literal and figurative blemishes of the body. To unlearn the stigma attached to a pochx kid — of not being Columbian, or Guatemalan, or Puerto Rican or lo que sea-rican — enough.

En dónde quedamos, y a dónde vamos?

I wrote this piece in response to two myths. The first is made possible by the racial optics of US immigration but is in turn perpetuated by American letters: que acabamos de llegar. That we as US Latinx poets are migrants twice over, both in land and genre. In reality, we have both written before publishers took notice, but we’ve also woven. As the children of immigrants, we text(ile) together the formally literary voices of our community (the percussive litanies of Juan Felipe Herrera, the stunning images of Nancy Mercado) with those in restaurant kitchens, fields, school hallways. We are ethnographers in disguise, documenting the overlooked art of Andres Montoya’s ice worker who “stack[s] blocks / of ice into rows of crystal perfection, / rows and rows, a huge army.”[26] But more immediately, this essay is an intervention against the unspoken white gaze on our art, one I’ve felt firsthand in renowned workshops across the US, that says the value in your work is the story of struggle, not its craft. All too often, it fetishizes the ethnicity of the poet, erases the agreed-upon barriers of author and speaker, creates a hierarchy where sprinkling French or German in a poem is seen as sophisticated, avant-garde, but Spanish as an impediment to understanding the work. As if all our poetry is just meant to be consumed for a readership wishing to educate itself on “the struggle.”

It is against this specter of what bell hooks called “eating the other”[27] that I maintain the hope that, across classrooms and street corners and podcasts and literary rincones all across this country, we can begin to seriously talk about Latinx poetry’s contribution to American literature (and vice versa). That we can begin to trace our heritage not just in ethnic terms but as innovations to a genre. Yes, there is an intrinsic value to our stories insofar as they humanize those populations ensnared in epithets: “bad hombres,” “caravans,” “illegal aliens,” and the like. As long as the logic of race reigns in senate hearings, in police checkpoints, against the housekeeper on a Marriot’s third floor, there is an inherent power to anthologizing our works on the lines of our shared memories that resist those daily threats. But what critics and allies alike forget is that we are artists, that the act of storytelling requires a command of the medium itself. That there is a formal dexterity and skill in our craft, one that merits the same attention our white counterparts would receive. It is with this double standard in mind that I praise the works of Karla Cordero and Melissa Lozada-Oliva. They paint the borderlands of country, body, and language with their spiritual and religious overtones, with surrealist and tech-savvy imagery. Their poems run the full gamut of structure — from jam-packed stanzas, to bleeding letters, to queered lines. They wrestle with wars, both the ones appearing in newspaper headlines and military tribunals and the ones too common to be called as such. They achieve such stunning craftsmanship not by accident, but through a sustained engagement with their literary forbearers. Let us begin doing the same.

1. US Census Bureau, “Facts for Features: Hispanic Heritage Month 2017,” Hispanic Heritage Month 2017, August 31, 2017.

2. Raúl Coronado, A World Not to Come: A History of Latino Writing and Print Culture (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016).

3. Rigoberto Gonzalez, “Lighting a Path for Chicano/Latino Literature in the New Milennium,” in Camino Del Sol: Fifteen Years of Latina and Latino Writing, ed. Rigoberto Gonzalez (Tuscon, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 2010), 15.

4. Melissa Lozada-Oliva, Peluda (Minneapolis, MN: Button Poetry/Exploding Pinecone Press, 2017), 5.

6. Karla Cordero, How to Pull Apart the Earth (Los Angeles, CA: Not a Cult, 2018), 27.

8. Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands = La Frontera: The New Mestiza (San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 2012), 3.

26. Andrés M. Montoya, The Iceworker Sings and Other Poems (Tempe, AZ: Bilingual Press/Editorial Bilingüe, 1999), 5.

27. bell hooks, “Eating the Other: Desire and Resistance,” in Black Looks: Race and Representation (Boston, MA: South End Press, 1992).