‘to be a boundless reflection’

On critical composition in Hejinian and Scalapino’s ‘Sight’ and ‘Hearing’

As a writing teacher, I am relentlessly bugged by the question of how to move students toward an organic practice of critical inquiry, to help them feel pulled by it at the most basic, creaturely level. In my search for a pedagogy that feels right and real, I look toward the texts that have become my own exemplars of compelling argumentation and analytic integrity, only to realize that my favorite works of critical writing are, in fact, poetry. This, I believe, is due to the characteristic ease with which poetry can investigate its own form: it is a manifestation of language that can’t relax into sonic, syntactic, or dictional givens but rather is propelled by formal attention every step of the way. It’s a craft that is inherently reflective in that the poet cannot proceed without attending to the writing’s physicality — a thinking that sees itself.

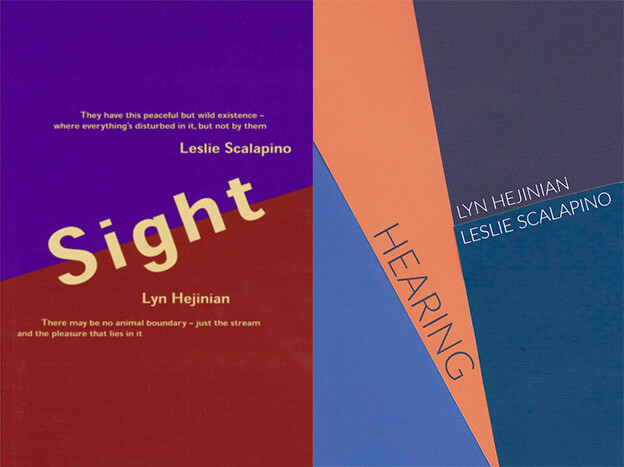

I like to let poetry’s innate reflectivity guide me in the process of composing critical prose because it helps me recognize the substrate of personal feeling upon which is built any critical position I find myself assuming. (I define “feeling” here as simultaneously sensation and emotion.) Lyn Hejinian and Leslie Scalapino’s collaborations represent a body of poetic work that consciously illuminates the feeling-content of critical-analytical processes, and they have become particularly influential to my conception of what sound critique looks like. They have written two books together, Sight and Hearing, that sustain visceral processes of reflection and self-reflection. The books were intended to be part of a five-volume series on the five senses, undertaking a commitment to sense perception as the human creature’s most essential means to interaction and thus to political engagement. Sight was published by Edge Books in 1999. Hearing was left unpublished, though nearly complete, when Scalapino died in 2010. A decade later, Hejinian finished it, and it was published by Litmus Press in 2021. The books are concentrated poetic investigations of what it is to be a body with sensory antennae that leash this self to other selves — this thing to other things — attending to the feeling of differentiating who is who and what is what. This overriding emphasis on reflection as a poetic act has the effect of collapsing the container into the content: writing as seeing, writing as hearing, has little hold on what exactly is seen and heard because it is propelled by a conscious effort to keep going, and the extreme precariousness of that effort causes content to slip away.

These works are critical works because they’re driven by acts of distinguishing — making out what is out there, letting it come into view so that it can be spoken of. In their separate oeuvres and in their collaborations, Hejinian and Scalapino have evolved a poetics in which analytical poetry and poetic analysis are regular and alternating activities such that the distinction between art and criticism all but disappears. Sight and Hearing speak directly to the dynamic relationship between action and observation in that both books assume the simple constraint of writing about what one perceives, visually in the first case and auditorily in the second.

Sight is prefaced by a dialogic exchange between the two authors in which Scalapino pens the words “experience is scrutiny,”[1] suggesting that one is always dislocated from oneself and that to feel things is to also feel oneself feeling things; moreover, it is to feel how others feel one feeling things. The book begins, and a process unfolds in which poetic utterances are traded back and forth, each signed off with its author’s initials, as “LS” and “LH” echo, reshape, protract, or refute each other’s poetic formulations. A rapport develops in which each recounted moment of sensation leans into contact with its reader, who will receive and translate the account, suggesting how an individual’s perception of the world is coformed by adjacent things and beings:

The sleep of my experience wakes in the stream of

Anything’s existence — I am leaning there [2]

In her essay “A Thought is the Bride of What Thinking,” Hejinian writes that the perceiver is always “under the pressure of abutment, contingency, and contiguity and hence constantly susceptible to change.”[3] Thus, we have the dialogic structure of these two texts, which refuse to forget, even for a moment, that their stanzas are subject to the influence of an interlocutor, whether it be human or inanimate. The stanzas move through different shapes, moods, and orientations, at moments faced fully outward toward the speaker’s physical environment:

In blackness whooing of two owls close to the ear loudly on bothsides, one’s hearing is not an action on one’s part and there is clear, black, soft. After the rain — the entire rungs — plateaux flooded — the cattle floating on the green rises, that were beside one — the rises horizontally were in-stilled by frogs, croaks as singing separate from evening light yet the rises existing as that

(LS) [4]

and at others turned toward the poetic dialogue at hand, facing the interlocutor:

It races in that it has no spoken occurrence or being, though it is language (your poem Happily). It flies, maybe slowly in that it has no time (‘having no spoken sound’ — which implies one). One has the impression of hearing it when it’s not spoken, as not a shape, sound or movement though it is language, is a sensation of being free? — though in more than one faculty of sensation at once or between some? So, though flying, it could be slow free. In fast and slow time even at once.

(LS)

[…]

I think nothing is free but maybe everything (at least at the moment of its incipience) is accidental (occurring in “free space,” i.e., in whatever space happens to be available at the moment it happens to happen). Freedom would be “outside one” but accident (happenstance, happiness) is outside one too. I would say this of love, too — it is outside one in the occasion (of friendship in listening reading). Your poem Deer Night is in itself, from within, listening.

(LH) [5]

The “it” in these poems is a recurring indicator of the ongoing nature of the dialogue at hand, with each speaker taking the other’s pitches and dilating upon them: there is always a web of thought that has been spun into something sprawling and complex and must be condensed into a diminutive “it” in order for the conversation to continue. There are no standalone poems because to pull out a single one would be to disrupt the push of conversation, its forward motion — it flies.

In this exchange, the mind of each poet catches its own sonic/conceptual resonances just as it catches the other’s. And each gives a nod to the other’s oeuvre. Happily[6] is answered by Deer Night.[7] The dialogue is conducted in a remarkably conscientious fashion: both know that “friendship in listening reading” must simultaneously be an energetic emanation (a feeling) and a directed deed (an act). The voice of an interlocutor forces into view previously unconsidered trains of thought and reminds one of the fact that a completely irreducible other entity is always nearby. That-which-is-not-one is held in one’s perceptual field such that even the dying are included:

The sky’s watchfulness is fluid, remembering

nothing, therefore a bipolar separation is in nature, has no relation

to one’s own mind, isn’t in the mind as if it’s not nature.

Then one could rest, as if one didn’t have to, aware

of faculty of resting which only is it

Not being that only one will die, when that isn’t

what’s groundless, they’re doing so is groundless

(LS)

The dying are included — this has to be implied by living

In the focus between (an open parkland in the background,

blurred trees) there’s interference, a muting of light achieved,

ghostly heat like that drifting down the beach

Disparity and asymmetry develop as ethical categories

Justice is inconclusive

a startling sound — merely

the whap of a flailing kid cannonballing

— creates a completely different picture

(LH) [8]

A landscape of chance encounters, unprecedented. A drifting, then a startling sound. Something utterly new appears — a completely different picture — such that the mind is, for a brief moment, overwhelmed, subdued, rebooted, and perhaps the utterly new something is also so, though one can never know. LH: panic comes from projected memory.[9] She teaches us how to face the task of filling a page while remembering nothing. The practice of critique-as-poetic-discernment that is undertaken in these two books invites the challenge of seeing without remembering. For the maps written by personal and societal memory — recording what combination of color and shape signifies what object, or what combination of facial features, demeanor, speech habits, and place of origin signifies what type of person — dictate the dominant human procedure for seeing. Speech and writing can indeed skip the panic that threatens them — the terror of being incomprehensible. There is a tight correlation between the influence of memory and the compulsion to identify. This influence is encapsulated in the copula, a form in which LS seems to take a great interest. Is, is in, isn’t in, as if it’s not, which only is it. Under the conditions of a language formed far before the singular perception that it tries to describe, words that identify and specify don’t ever hit their mark, but do a good job of tracing an act of trying.

The appeal of precision, the drive to identify and specify, has great directorial power over one’s way through language. In the face of this, a writing can emerge that is moved by an interest in the inevitable asymmetry and waywardness of its own attempts to say what it means. The walls that the writer butts up against never cease to exist, but they do change: one finds a crack in the system through which to escape, only to then discover new walls and new cracks. Hejinian wants to “write a poem which [is] to its language what a person is to its landscape,”[10] a poem that perceives its own limitations, moving through grammar, syntax, and vocabulary with open eyes and ears —

the pale white face tunneling runs through the bright air, with the

enflamed trees, that having shot up ‘before’ early, can burn as only

color

(LS) [11]

— like an animal moving through its environment, sensing the rules of nature and noticing how they can best be engaged toward fulfilling one’s needs. This resourceful perceiver is as complicated and porous as the poem is, ingesting the materials around it — an evolving and composite being: as I move through the space I read, I notice how different a thing looks from the time I approach it to when I’ve just passed it.

The epistolary format of Sight and Hearing amplifies the Socratic character of critical discourse as such: the fact that criticism is fundamentally an interjection into a particular time and place by, on the one hand, a particular speaker whose audience and setting determine what it is that needs to be said and, on the other hand, a particular listener whose historical and cultural specificity will condition a particular set of responses and resistances. Moreover, this dialogue between speaker and listener necessarily engages with the larger context of the public (or republic) as the urgency of getting one’s point across will always arise from the feeling that something in the greater world is lacking. Yet, while critical discourse always has the appearance of being around or about the point to be made — this something lacking — criticism that truly breaks through the surface of what is already known and said cannot be about its topic or point. Rather, it is constantly producing it, and the more words spoken, the more points apprehended. Perhaps in the end, the absent thing that criticism most wants to grasp and share with the world is the desperate persistence of the self’s own dislocation, the very structuring principle of language. Writing is an indication of separation; it is thinking a degree removed from experience, and the quality in it that separates ourselves from ourselves and from our embeddedness in the world is “a shadow (evocation) of that which is ‘exterior,’ the public.”[12] When, through writing, we look on our thinking, we’re assuming the role of the public. To put words on a page is an act of making oneself seen, and therefore, perhaps a substantial component of the writing’s content will be an expression of what it feels like to be seen and of why one wants to be seen. The composition that is made in an academic context will be especially resonant with that feeling of being looked at, and the visibility will also be felt as a submission to being assessed and measured. I am interested in compositional practices such as Hejinian and Scalapino’s that actively contend with the sensation of being called upon by environing objects, people, expectations, standards, institutions, and systems.

A mentor of mine once said something to the effect of: “the language that comes most naturally to one is built from the voices of everyone else in the room.” How to speak with a genuine, deep awareness of why we are speaking and what we are saying is largely a question of form. And it is an inherently political question, with life-and-death stakes.

Parataxis and poetic thinking

Sight and Hearing model an ethic of criticism that sees the critic’s primary obligation to be the bodily and site-specific activity of looking and listening, where observation doesn’t crystallize in reportable results. Hejinian and Scalapino do regularly spiral away from the sensory — like the impulse to light a cigarette during a moment of intense interaction — into pages-long analytical dialogue about the nature of perception, but these digressions from literally the matter at hand become informational fodder for further sensory investigation as the two poets turn their attention to the visual and aural ingredients of their own thoughts and words.

Do Hejinian and Scalapino, conversing poetically, access an intimacy with the material universe that I, in my present role of critical writer, cannot have? Deprived of poetry’s inherent liberties, is the critic/essayist irreparably blocked from the world by concepts? And, if I may nudge this line of questioning back toward my initial provocation, is there a valid pedagogical reason for us to continue emphasizing the prose essay — with the grammatical and syntactical constraints it imposes in maintaining the sentence and paragraph as its basic units — as the single most important written form that all students learn? I have found Theodor Adorno’s formulation of the relationship between poetry and criticism to contain some intriguing answers. For Adorno, — whose best-known philosophical works use notoriously never-ending sentences to articulate dizzyingly self-negating propositions — the essay lives between science and art, containing the scientific drive toward explanation and resolution yet preserving the artistic capacity for a heightened intensity of form and material. In “Parataxis: On Hölderlin’s Late Poetry,” he elaborates the concept of “poetic thinking” (Gedichtete), the ability to grasp at once a number of disparate elements that signify an unspoken something exceeding any unifying intention.[13] This form of thinking is proper only to poetry, as the poem’s very structuring principle. He contrasts it with “the logic of tightly bounded periods, each moving rigorously on to the next”[14] that is inherent to the prose essay. Poetic thinking is a visible, though ever-receding, horizon for the essay, whose perspective is plagued by “syntactic periodicity,”[15] the overwhelming impulse to synthesize, to unify. All language is fundamentally plagued by that impulse, but we might define poetry as the maximum threshold of language’s ability to not be what it fundamentally is. The essay trails behind, and yet, it is in its attachment to synthesis where its very power lies. To Adorno, the essay has the capacity to reach “a synthesis of a different kind, language’s critical self-reflection,” a form of unity in which “not only is multiplicity reflected in it … but in addition the unity indicates that it knows itself to be inconclusive.”[16] This potential goes unacknowledged in the critical essay that presents a carefully plotted logic, proceeding smoothly from introduction to conclusion, as a way of convincing one’s audience of the soundness of one’s position. Such a work falls short of achieving deep criticality as the performance of certainty and the legibility of the plot testify to the writer’s use of linguistic trails that have already been blazed. On the other hand, when the essay displays its own striving toward unity as a necessary failure, the failure becomes a locus of truth, and this is where the most revelatory critical activity happens.

Parataxis is a key principle in Adorno’s conception and practice of the essay. To him, paratactical prose will naturally resonate an indelible striving toward conclusiveness, but unlike hypotaxis, the grammatical mode in which phrases and clauses are subordinated to each other, it will not have to signify any belief in its conclusions. Proceeding through ideas paratactically will reflect both the disjointed agglomeration of physical things in the world that sparks the will to think and the live act of thinking that is always impelled toward resolving the disjunction. Poetry inclines heavily toward multiplicity, criticism inclines heavily toward resolution, and the paratactical essay inclines toward both.

Throughout my earlier analysis of Hejinian and Scalapino’s poetic collaborations, I have woven in text gleaned from their respective prose oeuvres, which are extensive. And yet, it is difficult to say definitively which of their works are poetry and which are prose; both authors have written book-length prose poems, poetic novels, philosophical essay-poems, works of criticism that move between the sentence and the poetic line, and books that are simply too transgeneric to be categorized. The following is an excerpt from Hejinian’s essay “The Person and Description,” in which, about halfway through, the paragraph as unit of meaning atomizes into free-floating sentences:

Coherence is always only contextual in this literary situation, which I can picture, for example, as a scene in which the writer is standing on a concrete curb in the commercial district of a busy city, the reader is standing beside the writer, and many, many people are moving up and down and across the street — many heads, many stomachs, many bags, many shoes and boots.

The person is gasping with explanation.

Your eyeball is on the person and with a check of the wobble you see…

A person has deliberately to keep all that can be seen in.

Every person is born preceded by desire.

Any person who agrees will increase.

A person, never less.[17]

In this essay on the unavoidable visibility of the subject/the perceiver/the inhabitant/the person even in a composition that purports to make it invisible, Hejinian is writing about writing about. Here, the environing objects and events that descriptive language wants to encompass are simultaneously encompassing it; the landscape for which the words reach asserts its own corresponding pull. The reader, too, is an actor upon this stage. And what allows the writing to cohere is not the writer’s ability to construct a logical sequence — logical because it has direction and purpose — but the fact that it articulates all the differing tangible objects and events that adhere to it and give it its shape. The result is a procession of clipped sentences. In a section of her essay “Demonstration / Commentary,” Scalapino practices her own form of criticism-as-poetry in a discussion of the films of Peter Hutton. Here, her conception of “the cut” resonates with Hejinian’s line break:

People’s language can’t imitate what is seen/what they’re seeing. There’s no language (as if ‘at all’ or that interprets people ‘there’) viewing — or as what’s seen.

So there’s a total separation between anything seen and expression.

The viewer’s activity of seeing is ‘expression.’

There is a total separation between expression as ‘seen’ or ‘seeing’ — and the cuts, silent and contentless, without sight/site, yet requiring attentiveness.

There not being either sound or sight in the breaks/cuts, the activity of one’s attention, in relation to just the film, is a terrain.[18]

The poetic splicing, the abutment, the staccato, the this-and-then-that, gives writing and film a certain truthfulness because it shows them to have abandoned any illusion that, as representational mediums, they have access to the uninterrupted, undifferentiated influx that is the unmediated experience of a person perceiving.

What lends the above works of critical writing their unity or cohesion is not the promise of a particular critical position toward which an accumulation of textual evidence will progress but the fact that they are being thought by a thinker and written by a writer. The centrality of psychological self-attention to the Frankfurt School project, which formed the social context of Adorno’s work, is to me a provocative correlate to Hejinian and Scalapino’s critical-poetic vision. The urgent aim of Frankfurt School philosophy was to figure out why human beings cannot help but participate in the development of totalitarian systems. The texts that emerged from this constitute what we now know as Critical Theory, representing a group of writers for whom practicing relentless criticality — treated as a balanced combination of psychological and social analysis, drawing from Freud and Marx — was the most important concern in philosophy.

Adorno’s experimentation with parataxis as a stylistic possibility for critical writing was an attempt to achieve the most concentrated and unwavering critical self-reflection possible. For both the reader and the writer, the jolt or cut that occurs between thoughts that do not proceed smoothly and logically from one to the next is a moment of self-reflection, of looking forward and looking back, that the masterfully composed argumentative essay will eliminate. In the process of writing an essay or a sentence (both of which are expected to have some detectable organization of beginning, middle, and end), this moment occurs for me when I’ve progressed just past the beginning: when I am compelled to feel accountable for whatever I’ve just said. When I pause to look back at the period preceding my sentence or the awkward first step I have made into the course of thinking that constitutes my in-process essay, it feels similar to waking up with a hangover, knowing I have to take responsibility for whatever I have just done.

So, my answer to the question of whether a poetic project like Sight and Hearing will necessarily do a better job than critical prose in accessing the layers of feeling upon which our intellectual inclinations are built is: not exactly. While the many-tendrilled images “flying with roots convulsed”[19] through Hejinian and Scalapino’s poetry enable a nonstop swirling-outward attention to felt stimuli, the forward movement of prose activates its own unique capacity. Blinkered unavoidably by the period that always lies ahead, it has special insight into one overriding sensation: the stressing demand for streamlined intentionality — a demand with which any writer who wishes to claim the role of essayist must contend. The writer in academia, whose immediate reading audience comprises rubric-wielding instructors, peers competing for professional opportunity, administrators with learning outcomes to enforce, or tenure committees manning the gates to stability and success, contends with this demand most pronouncedly. And yet, categorical distinctions — whether prose or poetry, observation or action, theory or practice — always contain a trace of that from which they are distinguished. Thus, I probe what Sight and Hearing might be by placing them next to what they probably aren’t, allowing proximity to do the work that definition and identification cannot.

Anxiety as critique

To identify the feeling of pressure imposed by the period — a signal behind me that I have begun to make a case, or a flashing reminder, always just ahead, compelling me to deliver a neatly tied package — is to recognize the act of writing as inherently a disquieting experience. The psychoanalyst and educational theorist Deborah Britzman has written about the anxiety that essay-writing tends to trigger. The stressing demand to say something — something smart, cogent, convincing, memorable, and new — is built into this role. As anxiety is a reliable tool for evading vulnerability, the anxious essay may contain clues about the specific vulnerabilities it diverts.[20] One of the ego’s defenses against anxiety is what she calls “isolation,” quoting Freud.[21] A major component of the isolation defense is the compulsion to perceive the writing as cut-off from the emotional situation it reflects. But that compulsion is palpable. Through writing’s performance of what it wants to signify, we can detect what it actually does signify. Writing is always at heart an attempt to make oneself heard and recognized, and therefore it tends to get stuck in the expression of egoic demands before it can achieve much engagement with the external world, which it perceives only in brief flickers. Yet, built into the very nature of the essay is the power to achieve, in Adorno’s words, “a synthesis of a different kind” as the anxious, emotional substrate will join the disjointed flickers.

The constellation of pressures that permeate the situation of writing is starkly obvious when it comes to the writer embedded in academia at any level: one’s direct audience of peers and superiors wields the power to make or break one, all of this within a system whose respectability depends upon an air of exclusivity and high standards. Britzman describes her own struggle to get words on paper while simultaneously fighting off professional anxieties:

While writing this paper, I lost my interest, felt no one cared, was sure someone else had already written it, and gave up hope that the disparate pieces of thought would take me any further than a description of what everyone already knows. Draft upon draft drove me into more muddles. I lost my train of thought and felt out of focus. Suddenly, I needed to read more. Then I began to hate writing. It was making me suffer.[22]

And yet, the fear Britzman illustrates above is something that is native to the act of writing in general: “words arouse anxiety and libido.”[23] The dislocation, the performance anxiety, the tender pride, the competitiveness are all part of the rich, emotional complex that is activated by the task of presenting one’s ideas in a written document with all its unalterable finality.

As poet-professors, both Hejinian and Scalapino contend in and through writing with the problem of creative autonomy in the face of institutional disciplining. If writing is the activity of self-invention — of becoming sharply cognizant of who, what, and where one is in order to better achieve who, what, and where one wants to be — it’s a process that may be stymied when where one writes is within the jurisdiction of an administrative hierarchy whose terms of assessment must be learned, accepted, and reproduced in order to continue receiving its benefits. Writing in the late ’90s, Scalapino remarked on a tendency in certain “poets accommodating the university setting”[24] who were aligned with avant-garde “procedural” practices to disavow experience as a valid basis for writing: “In order to be called ‘avant garde,’ the gesture would have to be devoid of its specificity per se (generalized as — or as if — modes or operations without entity) — and without the practice or the perception’s urgency or disturbance.”[25] While the “procedural,” “avant garde,” or L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E writers to which Scalapino refers were, by definition, excellent at challenging norms of communication — academic or otherwise — through a radically particularized reconfiguration of the English language, she views them as still reproducing the institutional criterion of disembodied objectivity.[26]

What is implied by the preeminence of subjectivity and “perception’s urgency” in poetic experiments like Hejinian and Scalapino’s Sight and Hearing is the wish for a heightened sensitivity to the stakes of being geographically, culturally, and politically embedded. Such work redresses the particular oversight that Scalapino observed to be prevalent among her peers: underlying their valorization of objectivity was the view that embodied experience is not a valid means to understanding political reality because subjectivity is culturally determined at the most primary level — it is never fully one’s own. Sight and Hearing pose an implicit challenge to the belief that the pursuit of objectivity is a path to clearer knowledge; they recognize that the muddying of vision that is caused by emotional investment is a part of the picture that is both unavoidable and instructive, as it is a means to perceiving how one is embedded. To experience my irrevocable cultural conditioning (or, to put it in a less dystopian light, the fact that I am coconstituted by all beings and things in my environment) reflectively is the only way to develop a conscious relationship to power, both in how it suppresses me and how I use it to suppress others. Through the many modes of textual listening in which Hejinian and Scalapino engage, writing can give up the doctrine of objectivity and still commit rigorously to exposing sociopolitical realities.

In American colleges, one of the first rules student writers learn is that they are not to use first-person pronouns: the performance of objectivity is key. The overriding requirement to articulate a good argument or persuasive research results means that the subjectivity of the writer becomes unnecessary and invisible. But the emotional impact on the writer of the demands that the educational situation makes will always manifest in the writing, where the voice of the subject inevitably persists.

The educational situation, Britzman argues, is inherently traumatic. First, the young child is removed from the only social environment they know — that of the home and family — to be placed in a world of strangers and presented with a new, disembodied form of knowledge acquisition with its own system of reward and punishment. In this context, the child relives the wish to please their parents, but now that need has been displaced onto the teacher. The earliest attempts at institutional learning are thus motivated by an ego-ideal: the wish to please in order to win love. It is only later that the genuine love of learning happens, which manifests at the developmental stage when the child becomes fixated on collecting things, an expression of visceral excitement for amassing knowledge. These different motivations for learning — the desire to please and the sheer love of intellectual activity — stick around for a long time; the writing of the college student will still be energized by them. Britzman writes, “the force of [their] emotional situation” is visible in the desperate wish to please a judging audience of professors or peers, and the “wish to risk that fate and create something new from more than what has already happened” in the manic spiraling of the paper that can’t find its “main point.” The particular kind of effort that the writing makes will always reveal a layer of meaning — much deeper than what that words purport to say — about the writer and the writer’s world. Britzman brings in the example of Roland Barthes’s The Preparation of the Novel, a book about “that which captures the writer and holds her back,” the anxiety that attends the work of preparing to write. Barthes recommends addressing this feeling through embracing and representing it. Britzman quotes his “neurotic solution”:

It’s possible to imagine, as a solution, a sort of neurotic stratagem or plasticity: depending on the nature of the problem or of the breakdown, you exploit the different neuroses within yourself; for example, breakdowns at the outset: defeating the page, coming up with ideas, provoking the spurt, etc. = hysterical activity ≠ the phase of Style, of Making Corrections, of Protection = obsessional activity.[27]

Such an approach, Britzman believes, will have the effect of illuminating the network of connections between the lonely, anxious, self-doubting writer and her sociopolitical universe:

Whether anxiety opts for the paragraph, sentence, or word, a story is being written and it is in writing that one may transform the writing phantasy into a commentary on problems in the wider world.[28]

The notion that one’s own cultural and psychological motivations that are articulated in any act of writing — including both culturally determined habits of thought and the idiosyncratic omissions and proclivities that the ego develops in order to defend itself — ought to be listened to rather than sidestepped is the core of Adorno’s vision for an education whose primary purpose is to prevent large-scale political violence. In his essay “Education after Auschwitz,” he advocates a “turn to the subject” through a pedagogy that emphasizes critical self-reflection above all else because he sees the disaster of fascism to have arisen from people’s readiness to strike outward against perceived transgressions in others while being unable to encounter what was malfunctioning within themselves.[29] “The willingness to treat others as an amorphous mass”[30] arises from a blindness toward oneself, where the inattention to one’s own motivations, habits, and biases results in a subjectivity that is itself nothing more than an amorphous mass. Adorno observes that mastery of the work that is asked of us within our institutional roles regularly requires the acceptance upon ourselves of pain and humiliation, which is achieved through great feats of repression in order to win the ultimate prize of power. Practicing toughness toward one’s own suffering will earn one the right to be cold toward the suffering of other people, and even to inflict pain on them; for with the achievement of self-mastery comes a license to avenge oneself for “the pain whose manifestations [one] was not allowed to show.”[31]

The intellect is shaped and propelled by forces of love and hate that have evolved in tandem with the thinker’s particular history and placement on this planet. At the core of the intellect is an emotionally reactive engine driving the thoughts one has and the cognitive habits by which one comes to them. The pretense to tell or teach one’s ideas as if they’ve been built ex nihilo by an author whose education, linguistic command, and persuasive ability lend written content the gloss of a precious metal will be inherently deceptive because the writer’s sensory and emotional situation always plays a significant role in informing what ideas end up on the page. I believe that the writing we most need will be sprawling, multiform, alien, and not even necessarily writing because it has flown away from the given categories of form and meaning that regiment thought as agreement and structure the cultural contexts through which we normally receive our texts.

In her introduction to Hearing, Hejinian reflects on the experience of writing in partnership with a beloved friend, remembering what it felt like to encounter together their very different perceptions of things: “One is wakened by the lack of reconciliation.”[32] The bivocal format of their collaborations unlocks for themselves and for their readers a capacity to feel the impact of a multivocal reality, one in which facts will be irreconcilable with each other while still ineluctably true. It can feel like a bombardment, or it can feel like life as it is and should be: multiple intricate stories colliding and a standing invitation for some element — any element — to momentarily emerge from the action and assert itself as watcher and documenter:

Two girls on bikes pass (like messages) through the leaves. One says “the brain is bristling on the shack” and the other says “the chain is strumming into the caution.” […] Dazed the dag wanders off — and that’s the last of the dag. The girls bike as if watching their ride together.[33]

1. Lyn Hejinian and Leslie Scalapino, preface to Sight (Washington, DC: Edge Books, 1999).

2. Hejinian and Scalapino, Sight, 6.

3. Lyn Hejinian, “A Thought is the Bride of What Thinking,” in The Language of Inquiry (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000), 7.

4. Lyn Hejinian and Leslie Scalapino, Hearing (New York: Litmus Press, 2021), 1.

5. Hejinian and Scalapino, Hearing, 42–43.

6. “Happily” is a book-length poem by Hejinian, published by The Post-Apollo Press in 2000.

7. Scalapino’s long poem As: All Occurrence in Structure, Unseen — (Deer Night) appears in the collection The Public World / Syntactically Impermanence, published by Wesleyan in 1999.

8. Hejinian and Scalapino, Sight, 13–14.

9. Hejinian and Scalapino, Sight, 11.

10. Hejinian, The Language of Inquiry, 203.

11. Hejinian and Scalapino, Sight, 57.

12. Leslie Scalapino, “The Cannon,” in The Public World / Syntactically Impermanence (Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press and University Press of New England, 1999), 22.

13. Theodor Adorno, “Parataxis: On Hölderlin’s Late Poetry,” in Notes to Literature, Volume Two, trans. Shierry Weber Nicholsen (New York: Columbia University Press, 1992), 112.

17. Hejinian, Language of Inquiry, 204

18. Scalapino, Public World, 33.

19. Hejinian and Scalapino, Hearing, 1.

20. Deborah Britzman, “Phantasies of the writing block: A psychoanalytic contribution to pernicious unlearning,” Academia (August 11, 2019): 21.

24. Scalapino, Public World, 57.

25. Scalapino, Public World, 57.

26. In “The Cannon,” Scalapino recounts an event from her academic career that illustrates this:

Giving a reading from As: All Occurrence in Structure, Unseen — (Deer Night), which is an intricate interweave, I included a passage, an overlay itself of seeing an impression (image) of blue dye on the surface of the eye only, dye that in fact in the circumstance is infused within the left side of the body of the person who thrashes being turned on a table.

A man speaking to me afterward referred only to the reference, in the writing, to the dye: “that sounds like something that happened to you,” with the implication tonally as well as in mentioning only that point in the writing, it is thus inferior

or that its happening explains the whole away.

it invalidates it by being experience (18)

29. Theodor Adorno, “Education after Auschwitz,” in Critical Models, trans. Henry W. Pickford (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005), 193.

30. Adorno, “Education after Auschwitz,” 198.

31. Adorno, “Education after Auschwitz,” 198.