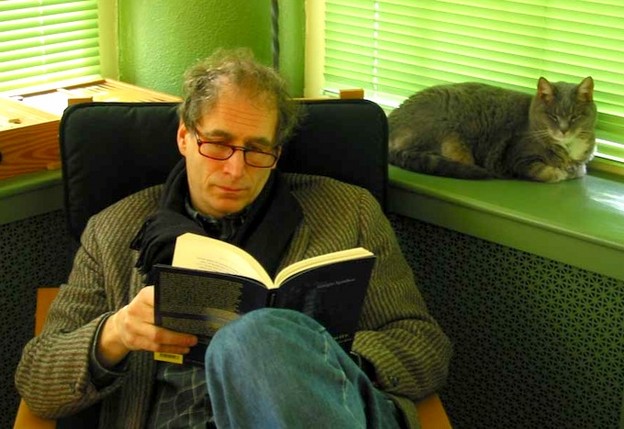

Bob Perelman's history

I've recently published a long essay on the poetry of Bob Perelman. It's called "The President of This Sentence." It's about the convergence in Perelman's writing of two parallel and also, at times, convergent analyses--one of modernism's rise and fall; the other of the state of Cold War at the point of giving way to New Left and countercultural skepticism. Here is a link to the whole essay, and here is the opening paragraph:

Bob Perelman a few years ago announced that he suffers from HAD (Historical Affective Disorder). He was joking, but not entirely. His history is sometimes a bit off, yet as for his historiography, especially in the verse, it is almost always perfectly pitched. Perelman disclosed his HAD in a disarming prefatory riff launching a long rejoinder to criticisms of The Marginalization of Poetry, a book of essays he published in 1996. His advocacy of a particular tracing of an avant-garde in that collection had been defended by, he had to admit, a “defiant army of defiantly non-avant-garde sentences hurled at the four coigns of the balkanized master page.” The historical disaffection here, the worst effect of the malady, was to have forgotten in his capacity as a critic the main form/content lesson of the very same modernist prose literary-historiography — learned from Williams in Spring & All and In the American Grain; and from Pound in his most dissociative essays — that was and still is Perelman’s own modernist ground zero. Or, as Ron Silliman forcefully noted, Perelman’s chief impairment derived from a move into the ivied academy, whereupon the book-length display of super-coherent strings of such “nonavant-garde sentences” (among other issuances of normative critical behavior) rendered unruly heterodoxy unlikely or impossible. Thus had our HAD sufferer tellingly — indeed, happily — placed himself at a distinct disadvantage. In the poetry, over the years, both pre- and post-Ivy League, such symptoms as issuing forth from Perelman’s special expression of historical disorder — (1) a keen and specific sense of how the American past operates in the present, mixed with (2) deliberate socio-idiomatic fuzziness and (3) a comic mania for anachronism — have always been the source of his finest and most remarkable writing. The greatest Perelmanian ur-anachronism of all — that there might not be a future of memory — produced verse in the 1980s and ‘90s that offers the most perspicacious understanding of the end of the first Cold War (the early 1960s) I have yet read in any genre. This work presents an analysis-in-verse that convincingly links crazy characterizations of anticommunist conspiracies to a generationally earlier history of the rise and later demise of the modernist revolution.