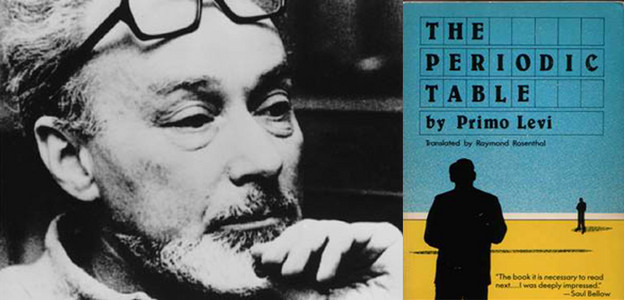

On Primo Levi's 'Iron' and 'Carbon'

Recently I was asked to speak for a few minutes about a Jewish writer I believe should be better known. Primo Levi certainly is well known, but perhaps more known of than read, beyond, perhaps, Survival in Auschwitz, which maintains something of a life on high school and college curricula as a partner to, or substitute for, Elie Wiesel’s Night. (They are utterly not the same book. Nor the same kind of book. But they feel to teachers somehow like bookends.) In any case, Primo Levi wrote several other extraordinary books, the most powerful (and by far most formally experimental) of which is The Periodic Table. It is a modernist epic in prose. It has none of the immodesty of The Cantos or Ulysses or The Bridge or Paterson, but it seeks, through genocide and meditations on science pedagogy, to make a whole gigantic statement about what’s elemental of the meaning we make, and its parts, elements of a table that it itself a supreme fiction explaining the whole world, do not add up to a coherence but yet do embody the world. Readers of this commentary will have read my praise of this book before, so I will not dwell on it here. But I do happily present my 17-minute talk on the book. Because of the time constraint, I had to choose what to say about several parts that would be representative of the whole, so I concentrated on the final paragraphs of “Iron” (a chapter preceding Levi's stay at Auschwitz, which is reckoned in the chapter called “Cerium”) and the final paragraphs of “Carbon,” the last chapter of the book, and its most (shall we say) organic. Organic in theme and celebratory of the fictive present-tense-writing self in form. Here is that audio: MP3.