Anti-ordination in the visualization of the poem's sound

Bernstein chants 73 through 75 in "1 to 100" (1969)

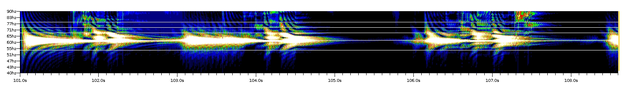

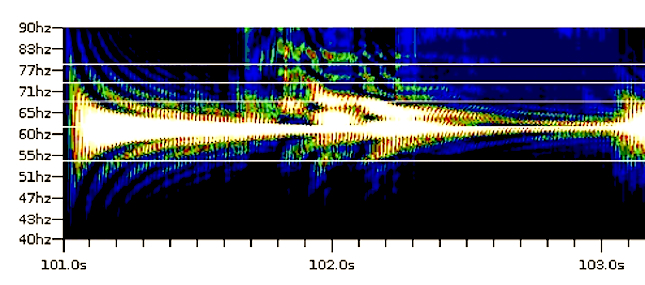

Through ARLO (Adaptive Recognition with Layered Optimization), enabled by the HiPSTAS (High Performance Sound Technologies for Access and Scholarship) project headquartered at the Information School of the University of Texas at Austin, I sought to visualize the later passages of Charles Bernstein's chanted/screamed list or counting poem, “1 to 100” (1969). Thanks to Chris Mustazza, Tanya Clement, David Tcheng, Tony Borries, Chris Martin, and others, I am finally learning how to use ARLO to some rudimentary effect. Every single PennSound recording is now available in a test space to which ARLO can be applied by researchers, including myself, associated with the project. We are just beginning. HiPSTAS has received two NEH grants to make all this possible, and PennSound is a founding archival partner. Through Jacket2 we hope soon to create a special o ngoing commentary space where PennSound-affiliated digital humanities scholars using ARLO can first learn to visualize and then create stable critical vocabularies for describing the sound of poetry as recorded. In this critical method, textual presence and reference are not necessary — although the emergent methodologies don’t seek ideologically to exclude the text as a parallel or ancillary or even a kind of control against the reading of a visualized soundform. We aim to see the sound of a poem performed, and, where possible, to start from scratch in effecting a method of close listening akin to, but not dependent upon, nor derived except conceptually from, close reading. In order to see what happens to the poet’s voice when Bernstein talks, chants and then, in essence, screams “1 to 100,” I chose numbers 73 through 75, at a point in the poem when the voice has begun to move from worded speech to much-purer-than-usual noise — a move we can take to mark a transformational moment in Bernstein's sense of his poetic vocation. ARLO enables one to make a .wav copy of the selected passage and here it is. The enunication of “seventy” in the articulation of each of these three numbers keeps the poet in the realm of words, while the stretching of the open-vowel-dominated single digit (“threeeeee,” “fooooooour,” “fiiiiiiiive”) attached to each iteration of the decade, is what moves the poet toward his endpoint of sound-without-sense. (Below at left you see the ARLO visualization of “73” only and can see the “3” stretched to the point where it meets the start of “74.” The greatest vocal disturbance occurs at “ven-ty” in “seventy,” followed by the release of the stressed yet breathed syllable “three.” Ty-fiiiiive makes for an odd iamb, with the stress eventually linking to the next number’s first foot in such a way as to dampen its own stress. Above at right one sees the ARLO settings here, including the very low damping factor. Obviously this kind of elision is extremely exaggerated and rare when a poem's words are uttered at such deliberate intervals; this kind of hyperextended elision happens routinely in song but very rarely in poetry.) Yet there is strong sense here, since listeners know exactly what is ordinately coming. Narrative expectat

ngoing commentary space where PennSound-affiliated digital humanities scholars using ARLO can first learn to visualize and then create stable critical vocabularies for describing the sound of poetry as recorded. In this critical method, textual presence and reference are not necessary — although the emergent methodologies don’t seek ideologically to exclude the text as a parallel or ancillary or even a kind of control against the reading of a visualized soundform. We aim to see the sound of a poem performed, and, where possible, to start from scratch in effecting a method of close listening akin to, but not dependent upon, nor derived except conceptually from, close reading. In order to see what happens to the poet’s voice when Bernstein talks, chants and then, in essence, screams “1 to 100,” I chose numbers 73 through 75, at a point in the poem when the voice has begun to move from worded speech to much-purer-than-usual noise — a move we can take to mark a transformational moment in Bernstein's sense of his poetic vocation. ARLO enables one to make a .wav copy of the selected passage and here it is. The enunication of “seventy” in the articulation of each of these three numbers keeps the poet in the realm of words, while the stretching of the open-vowel-dominated single digit (“threeeeee,” “fooooooour,” “fiiiiiiiive”) attached to each iteration of the decade, is what moves the poet toward his endpoint of sound-without-sense. (Below at left you see the ARLO visualization of “73” only and can see the “3” stretched to the point where it meets the start of “74.” The greatest vocal disturbance occurs at “ven-ty” in “seventy,” followed by the release of the stressed yet breathed syllable “three.” Ty-fiiiiive makes for an odd iamb, with the stress eventually linking to the next number’s first foot in such a way as to dampen its own stress. Above at right one sees the ARLO settings here, including the very low damping factor. Obviously this kind of elision is extremely exaggerated and rare when a poem's words are uttered at such deliberate intervals; this kind of hyperextended elision happens routinely in song but very rarely in poetry.) Yet there is strong sense here, since listeners know exactly what is ordinately coming. Narrative expectat ion, we might call it, is the quality of listening here that draws the sound back to speech. Yet despite the strong pull of numeration, it's at this point in the piece that one begins to forget or neglect intrinsic finality in favor of the chant’s anti-teleological effect. ARLO enables me to minimize the damping of the sound, so that the stretched digits can be seen and visually compared as Bernstein moves to the Zukofskyian upper limit of music in his journey as a young poet away from the lower limit of speech — away from the semanticism of the poetry against which he had begun to rebel. The poem's resistance to teleology is best apprehended through its sound; its textuality, such as it ever was, moves in the other direction.

ion, we might call it, is the quality of listening here that draws the sound back to speech. Yet despite the strong pull of numeration, it's at this point in the piece that one begins to forget or neglect intrinsic finality in favor of the chant’s anti-teleological effect. ARLO enables me to minimize the damping of the sound, so that the stretched digits can be seen and visually compared as Bernstein moves to the Zukofskyian upper limit of music in his journey as a young poet away from the lower limit of speech — away from the semanticism of the poetry against which he had begun to rebel. The poem's resistance to teleology is best apprehended through its sound; its textuality, such as it ever was, moves in the other direction.