David Eggleton

Aotearoa New Zealand's Poet Laureate

David Eggleton is the current Poet Laureate of Aotearoa New Zealand. He was appointed in 2019, and his tenure has been extended until 2022 because COVID has thwarted several of his live appearances.

David Eggleton is of Caucasian and Rotuman Fijian/Tongan heritage. Accordingly, he is a Pasifika poet.

I have known David ever since we both went to the same South Auckland, New Zealand, schools waaaaay back in the 1960s. Indeed, we were in the same classes at Aorere College, Mangere, where David had a definite proclivity for compiling vocabulary. I recall once presenting him with the triad “copious, abundant, plethora,” which he noted was good, nodding enthusiastically.

Eggleton loves words, most especially esoteric, arcane, and interesting lexis, which he crafts into his cadenced poetry with considerable care. His poems are vital verbal extravaganza and this — along with his indomitable delivery style, itself rhythmically syncopated — are hallmarks of his work as a poet, given that he is also a writer across several other genres such as art criticism, literary reviews, and editing, and holds other roles, such as a recording artist. His poems abound with layers of colourful imagery, often adumbated, so that their overall patina is distinctive: one can often recognise his distinctive work even if his name does not appear on the page.

More than this abundant imagery, there is a plethora of witty, sometimes quite acerbic, social commentary in his work, with references to current events, personages, and concerns dished out rather copiously and oftimes in vernacular; the reader may have to reread a line, a stanza, more than once to completely grasp Eggleton’s poetic gesticulations.

His work is best heard and seen performed, because Eggleton traverses his verses with a swift tempo, and his speciality is the manner in which he usurps regular metre and produces a rhythm of his own. In his early years he was named the Mad Kiwi Ranter, and although he has slowed down somewhat, the accolade is still relevant in that much of his poetry — even the far less frenetic more recent work — eyes as its target societal imbalances and is often delivered as a chant-like mantra.

By the way, he is not “mad” in any sense of that word, never has been.

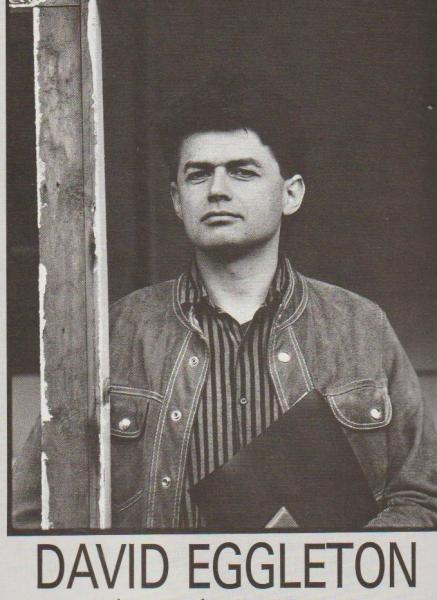

The young ranter. Photo courtesy of Robert Cross.

Let us look at a recent poem by David Eggleton.

Are Friends Electric?

Too much smashed glass on asphalt,

swerving in and out of the bike lane,

you got skaters, scooters, vapers,

someone taking selfies with boozers.

Everyone is insane after dark,

by the locked park gates;

and where do you park so no-one

can pancake the car roof off a balcony?

Someone’s playing housie with a trust fund,

someone’s put the rent up on white fragility,

someone’s hurled cookie dough on the pavement.

Fang it, prang it, walk away totalled,

who got the price tag of that?

Shuffle to the muffler, raise the wheels,

or tow it away from the harbour,

after raising it out of the water.

Seepage, salvage, knock-down heritage;

raise up flower power in gardens.

Let the chips fall where they may,

on airwaves, sheathed in hagfish glue,

or stuck to the highway way back,

when yesterday was some place to be.

Asphalt shades of greyscale

unscroll a doomslayer’s papyrus,

its dried-up syrups of blood, lead, nitrate.

Gaps are bridged by signs, years by stars

that might scratch your eyes out.

The fevered rain is not enough to wreathe a sinkhole.

Cram cranberries in your gob by the handful,

and click through dross after dross on ways

to improve the biosphere from inside your silo.

The checkout counter, like your personal biomass,

counts somewhere, maybe.

And you were born and raised in a coffin,

and now you're an astronaut on a mission,

your ashes are launched from a circus cannon,

towards a trampoline you preordered,

from your parked-up car above Lover’s Leap.

Peeps are posting pics of themselves planking,

or leaning away from the goalposts,

looking down on a mass grave called Planet Earth.

Ashes drilled into the skin with a needle are blue.

Here you have it — assonance, metaphor, personification, alliteration, simile, internal and irregular rhyme and line/stanza length, near-rhyming words, repetition, the incursion and capture of song and/or book titles, etc., are all assembled into an idiosyncratic and dense verbal forest with pronounced daubs of light, shade, and hue rippling throughout. Often rather lengthy too. The reader/listener is drawn into the texture of the poem and becomes a part of the tropical scenery. Do you remember those kid-toy kaleidoscopes where the flashing colours and patterns revitalized your vision? Reading much of Eggleton’s work — especially if read consistently and consecutively — has the same effect, although as his career voyaged on, it etiolated away from brute force rhyming couplets toward more descriptive and perhaps less dynamically in-your-face dynamite verse.

David’s ascent to his current position as leader of the local poetry scene, has — to me, at least — always seemed inevitable. He has been a published poet since before 1986 when South Pacific Sunrise was launched (I recall drinking several glasses of chilled white wine at the Auckland launch, along with John Pule — like David, a Pasifika artist. John is Niuean). Since then he has ascended a series of accumulating pinnacles. Here is a list of some of them:

1985: London Time Out’s Street Poet of the Year.

1987: His South Pacific Sunrise won PEN Best First Book of Poetry Award.

1990: Robert Burns Fellowship at Otago University.

2004: Copyright Licencing Ltd Writers Award.

Up until 2009: A six-time winner of the Montana Reviewer of the Year Award.

2015: Janet Frame Literary Trust Award for Poetry.

2016: Prime Minister’s Award for Excellence/Literary Achievement in Poetry.

2016: His The Conch Trumpet won the Ockhams New Zealand book Award for Poetry.

2017: Fulbright/Creative New Zealand Pacific Writer’s Residency.

2010–2017: Editor of Landfall, the country’s leading literary publication.

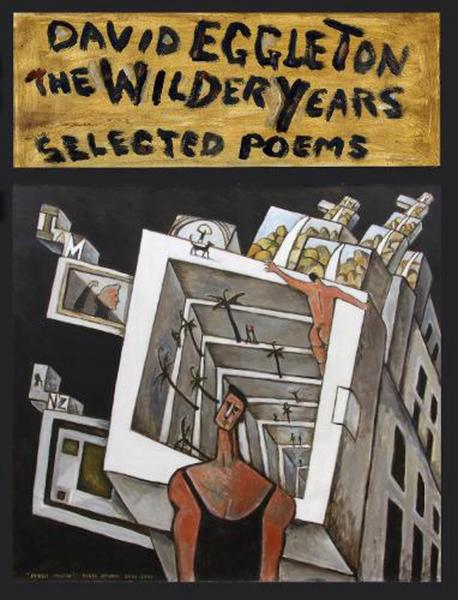

To date ten collections of poetry. His selected collected works entitled The Wilder Years (Otago University Press) is due out about NOW.

Wow! A storied career indeed. A deserved current position, then, which — as noted — has been extended a year, due to the ravages of coronavirus stymying David’s ability to perform — often literally — his role throughout this skinny country, Aotearoa New Zealand. Of course, the role of Poet Laureate entails faaaar more than reading poems at public events. They maintain a blog, as here.

-

I interviewed David. Here are his thoughtful responses to a set of questions ranging over his rather prolific poetry (and prose) career. He certainly articulates much better than I the way he embodies poetry in his every living moment.

1. Thinking back to your early years, up until publication of South Pacific Sunrise in 1986, were you conscious of developing a distinctive and deliberate poetic style — both (the rather rapid) performance and (rather profuse) written — back then? Or were you “only” expressing inner feeling, and experiences, as your momentum?

Slang, buzz words, brand-names, the transistor radio’s Top Twenty Hit Parade. My life as a poet began in South Auckland at school out of a miscellany of “happenings” in the late ’60s, from the mantras of the beatniks and the hippies, to the slogans of political liberation movements, to the jingles of consumerism, and, above all, in response to rock and roll music. In that, I am typical of my generation, which also produced Chris Knox of the Flying Nun record label and Tim Finn of Split Enz, though they were from middle-class backgrounds, with all the self-confidence that implies, while I was from an emphatically working class background.

For me pop music was poetry, and I sought to emulate it, entranced by its language and the aural delivery, but I was always thinking as a poet or at best a lyric writer, never as a musician. At school we read Gerard Manley Hopkins and T. S. Eliot and discovered Gunter Grass, James K. Baxter, and Hone Tuwhare. But it was listening to “I Can Hear the Grass Grow,” “These Boots Are Made For Walking,” “A Whiter Shade of Pale,” and “Subterranean Homesick Blues” that turned me on to poetry in performance. Suddenly, the schlockerama of TV sitcoms, the cartoonery of Mad comics, and the wild paintings of the German Expressionists became galvanising. I turned into a subterranean Dadaist-Surrealist, producing souped-up free verse that craved an audience. Eventually, I started to get up between bands performing at various venues and recite my zany verse that sounded like the babbling product of a misspent youth growing marijuana plants in wardrobes, hanging out in dingy bars like the Snakepit in downtown Auckland, and skiving off to Rolling Stones and Led Zeppelin concerts at Western Springs stadium. Eventually I connected with the nascent punk, rap, and reggae scenes that were burgeoning and fermenting all over New Zealand, and in my case specifically in Auckland, Wellington, and Dunedin. From here, I began performing with other poets and musicians at the Globe Hotel and in Streets Ahead Cafe and so on, and never looked back. Poetry is a go-anywhere-art-form but the key word in that phrase is “art,” and art requires craft, so that for me careful crafting of language following on example and literary tradition was crucial while using the vernacular speech for its energy. In fact I wrote energetically across the spectrum of poetic forms while employing my own mosaic technique, adapted and adopted from many models [Rapatahana highlighting].

2. As time went on, you became a very noted reviewer and a writer of several books which were not poetry orientated. For example, you are also an articulate critic and appraiser of art. Do you think this diverse range of authorial approaches fed into and developed your own work as a poet? If so, how?

I wrote about New Zealand culture as part of my neonationalist project to better understand the small insular nation I grew up in. Arriving here on this green archipelago in the South Pacific as part of a family of migrants whose roots were in deep the isles of Polynesia (Fiji, Rotuma, Tonga) as well as the British Isles, where the nostrums of Empire-building exported sailors, soldiers, and — as in the case of my father — airmen, to far-flung British settlements, we were encouraged if not ordered to “fit in.” Growing up in New Zealand was all about assimilation to a monocultural monolithic entity, which hid and censored its divisions and differences with an airy she’ll be right philosophy, but by the aggro-a-gogo decade of the 1970s the cracks were showing, and soon political protest lead to a new evaluation of Māoritanga, gay rights, women’s rights, and the rest. So my cultural writings, begun from the viewpoint of an outsider [Rapatahana highlighting], someone outside the charmed circle of settler culture, sought to articulate chronologies and movements and reasons for change in art, music, photography. Beginning in 1990 until more or less the present, I also wrote extensively and prolifically about contemporary NZ literature, theatre, art, dance, architecture, photography, and so on in newspaper magazine and literary journal reviews, believing not that literature and art was an elitist activity best confined to universities, but something available to all. These writings over three decades constitute an uncollected panorama of artistic activity in this country — and in keeping with this nation’s devotion to “Awardism,” they have also consistently, year by year, won me the Best Reviewer Award or else been shortlisted.

3. The Landfall years saw you take on the mantle as overseer of the country’s most respected literary publication. Can you summarise your own takeaways from this position, e.g., what did you see develop in the country’s literary approach (if anything!), and what did you hope to nurture as editor viz the country’s literary output?

The founding of a national literary magazine of the sustained quality, intensity, and vision of Landfall, begun in the wake of World War II by Charles Brasch, was an epic act, part of nation-building. He sought to emphasis the concept of “civilisation,” which to us now seems implicitly colonialist. By the time I became editor, the mission statement had changed radically, and somewhat erratically as postmodernism and other antic trends came and went. Yet in a way the maintenance of literary standards was a touching belief to be cherished and indeed “maintained.” I was overall editor between 2010 and the end of 2017. The editorial torch had passed through many hands before it reached me, but I grasped the underlying potential — the institutional trust the publication had inherited — and sought to keep up those “literary” standards. Mine was a stabilising and shaping approach that sought to emphasise solidity and permanence, that is to say reliability and consistency, rather than novelty and faddishness, and “experimentation” for its own sake as a kind of dessicated formalism.

In the end, my contribution could be viewed as a kind of last-ditch stand against fragmentation, atomisation, and the rejection of Braschian values. Now, it could be argued, Landfall is shaped by the demands of the market and of creative writing classes for outlets for a kind of therapy-driven writing and a deconstructed/reconstructed “self” in the wake of neoliberal globalisation and the countervailing rise of identity politics. Yet, ultimately I believe the cycle of literature as commemoration followed by defacement will continue. Literature provides both shelter and a kind of entombment. It is a cultural landscape and in these shaky isles, fissiparous, volcanic, tectonic.

4. You are currently Aotearoa New Zealand’s Poet Laureate. This storied position consists of more than a fine poet reading their poems across the country. What are the aspects of this important role, other than reading your own work? Have these latter two positions affected the development of your poetry, again regarding performance and written on the page? If so, how, please?

With “Te Kore,” my tokotoko, my taiaha, my orator’s stick, I lead the big parade on behlf of New Zealand poetry for the length of my term which ends on National Poetry Day in August 2022. I advocate for poems and for poetry, and ultimately for that great abstraction “Poetry” that which expresses wairua, the soul or spirit of the nation. Each Poet Laureate chooses to advocate in their own way, there are no hard or fast rules laid down for us. Some of the things I am involved with are Festival poetry readings and panel discussions, I might write poems about matters of national significance for publication on a variety of media platforms. I helm poetry sessions for other poets, and help edit a variety of poetry publications, including Ōrongohau | Best New Zealand Poems 2020. There have been and continue to be school visits, poetry craft workshops, mentoring, keynote speeches, corporate function presentations, assorted committee meetings, poetry-judging, and in these COVID-19 benighted times, endless Zoom poetry readings as part of overseas festivals.

5. Finally, what does the future hold for David Eggleton as pertaining to publications, roles, promoter of — for example — Pasifika poets in New Zealand, and other avenues?

For the whole time of my tenure I am responsible for a Poet Laureate blog on the New Zealand National Library website on which I regularly post new poems and poetry commentaries, as well as poems by invited guest poets. This encourages me to produce poems in response to current events of national significance. I am also working on chapbooks and a new collection. My Selected Poems is launched this May 2021 in number of events around the country. Following this, I shall keep on keeping on.

-

Eggleton — above — touched on his early outsider status, yet he does remain very much a mainstream literary figure, as per his comments about Landfall above, and indeed earlier, in a Jacket2 commentary I penned several years ago, as here — “It is intended that the Landfall Review Online commentariat maintain the dignity and authority, the measured approach, the essentially sober [Rapatahana highlighting] tone that Landfall has endeavoured to pursue offline.”

Similarly, as per my comments in that same commentary entitled Three Southern Gentlemen, “Mainstream, essentially, as they are English language poets all and generally speaking, would not be seen as ‘experimental’ poets, given David Eggleton’s earlier more varied performance ethos and activities, among them as recording artist.”

Yet there remain what I will term edge-aspects that Eggleton retains as the perennial commentator, the critic, the outlander looking at and into New Zealand culture and its many and varied vicissitudes. He bestrides both the tralatitious and the idiosyncratic and does it with agility, political astuteness and is a survivalist par excellence. (Incidentally, his 2015 collection was titled Edgeland).

Which leads to my conclusion. There is no personal evisceration or indeed much self-reference in his poetry. For example, during the entire fifty-three poems in The Conch Trumpet, the word “I” appears only twenty-one times, and three of these are “I’m.” Eggleton is not a confessional poet. He never strips himself bare, nor creates profound paeans to lovers. It is only in some work like the aching Between Two Harbours do we experience his pain, his profound sense of loss at the demise of his father. In the end, then, the poem is the platform for profound life experiences and it is in poetry that David Eggleton is inextricably and existentially bound. It is his lifeblood. When all is said and done this man lives poetry. He eats it for breakfast and dines on it for dinner. As here:

I Want to Write a Poem

I want to write a poem

the colour of paracetamol,

the colour of Pinot Noir.

I want to write a poem

like an impetuous kiss;

a poem like a sloth,

reaching for the last jungle branch

before the plantation begins.

I want to write a poem

like a tight-rope walker

between the Twin Towers,

lit up by the rays of another sun

and a heavenly host of planets,

announcing God is great.

I want to write a poem

like a box kite,

a poem like a blue sky day,

a poem like a nor’wester in summer.

I want to write a poem

like a rusted car wreck,

like a collapsed bridge,

like a random punch,

like a sly foot-tap,

like a Māori haka,

like a fresh death mask,

like peel-off future proofing,

like the smile of a stolen girlfriend,

like the scent of Adieu Sagesse,

like gravestones, like time-bombs,

fractal geometry, orchestra tom-toms.

I want to write a poem

like the twilight zone,

like righteous incarceration,

like the steady pit-pat of the rain.

Finally, a couple of links to explore this important — should I say necessary —English-language poet’s oeuvre further, including the NZEPC site’s valuable compilation of several the stages of his looooooong literary lambast, and a Poetry Archive site where we can listen to his lyrical litanies.

Tēnā koe Rawiri. (Thank you David — in my own first tongue).

Reading at the Lounge, University of Auckland 2021. Photo courtesy of Tim Page.

Feasting in the Skinny Country: Aotearoa New Zealand Poetry