Three new talents

Three New Zealand poets with something vital to say

Kia ora. Talofa lava. Malo. Greetings, once more.

I am honoured and humbled to continue to commentate on poetry and poets in Aotearoa New Zealand, which swerve away from so-called ‘traditional’ ways to write a poem and concomitantly, away from traditional topoi.

In this commentary, I will extend from my final commentary post of March 2016, which was entitled ‘Coda 2,’ although that title is obviously a misnomer, as this country just keeps on producing poets of great ability, with serious credentials and a willingness to s t r e t c h the paramaters of what a poem is, should be.

So, I am privileged to here introduce three further women writers — Hera Lindsay Bird, Simone Kaho and Mere Taito. All have recently had published new collections of poetry: the ‘new’ in this commentary title refers to this aspect — for all three have been writing poetry for some time. For me, they are intelligent, rather intensely tremendous talents.

I think that I will here replicate what I wrote in that ‘Coda 2’ piece, as the sentiments are exactly the same —

All three fit, if you will, the parameters I claimed would establish the future direction of an increasingly multicultural country. None of them could be classified as pākehā middle-class poets and all tend towards the experimental and/or performance and/or indigenous striates of poetry. Significantly and obviously, all three are women. Theirs is the future of poetry in the skinny country of Aotearoa — inevitably, for as I have stressed several times previously — the demographic of Aotearoa is rapidly and rather radically on the move into major diversity.

More, these three writers involve themselves in shared self-reflections about their own layered identities — ethnic, linguistic, cultural — in this zone of change, that is Aotearoa.

Just like the inevitable future national flag transformation here, away from union jacks and governor-generals, poetics here will inevitably reflect more and more female, multiethnic poets of spirit; who swerve off in directions from so-called mainstream verse, while writing and performing in forms of English far from so-called standardized English, if indeed they even write in that language at all.

I will present what these poets have to say about New Zealand poetry and their own poetry per se — in alphabetical order.

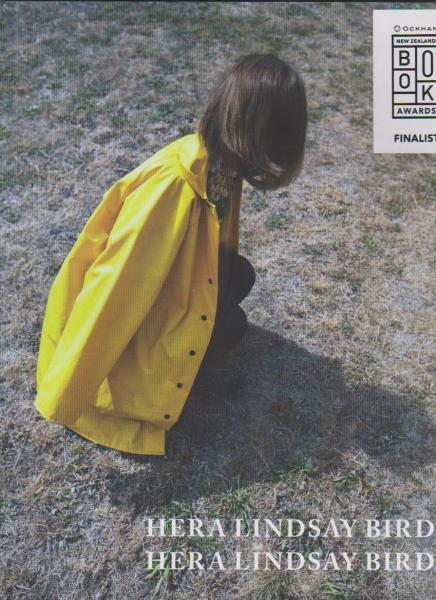

Hera Lindsay Bird sent out seismic tremors with her fine first book of poetry, entitled with the eponymous Hera Lindsay Bird! Why? Primarily through her candidity, her willingness to broach without blushing, female sexuality in her work, as well as a spring cleaning of the musty museum of this country’s poetic conventions. Always with a sense of serious humour and often with a surprising and imaginative turn in poetic portent. I also feel that Hera’s answers sum up several contemporary directions in and for our poetry well (see her comments about punctuation, for example) — without any need for me to extrapolate.

Would you define yourself as a Kiwi poet having a perspective that is different than the ‘normal’/mainstream (i.e. generally Pakeha New Zealander) one? If so, how so?

I think my work has a different aesthetic sensibility than a lot of New Zealand writing & it’s probably more similar to contemporary US poetry than our homegrown stuff, but I think that’s the main difference! I actually think of my poetry as pretty traditional in most ways, although perhaps there are also some generational differences in language and punctuation. I have to admit I don’t really think a lot about the category of ‘NZ Poetry’ as a whole, because I grew up reading poetry primarily on the internet, and so those categories are less meaningful to me.

Do you deliberately concentrate on different and distinct themes, imagery, stylistic devices, and do you ever employ other tongues (words/languages) in your poetry?

I think every poet has a couple of thematic preoccupations and types of linguistic tricks they pull out regularly. I love stacking similes and metaphor, repetition, long narrative poems, and plenty of other things, including extravagant ellipses (a device stolen from US poet Chelsey Minnis) but it’s always changing. Most of my poems are love poems, so that broadly covers the thematic element. The new linguistics of the internet age, particularly the shift towards a less ‘correct’ but more emotive system of punctuation is really fascinating to me. For instance, nobody under the age of forty ends their messages with a full-stop anymore unless they’re wanting to convey displeasure, and starting your sentences without capital letters is less formal — there are so many unspoken rules to do with commas, line breaks, and ellipses that affect the mood of a sentence in very specific ways. They’re almost entirely intuitive and unwritten, but they’re deeply sophisticated in what they’re able to convey. There’s this funny phenomenon now where people’s text messages from their parents or older family members are read as impossibly harsh and unfriendly, just because the generational codes are so different. I like to play with those in my work when I can.

What would you like to see more of in Aotearoa poetry from your point of view as a poet? In other words is there sufficient recognition, publishing scope, critical space given to (newer) writers who craft their work in ‘different’ ways … ?

To be honest I feel like New Zealand poetry is in good hands! The new generation of poets who are just starting to publish consistently blow me away, and are already burning down the great castles of NZ literature and building strange new ones with fire escapes and waterslides in their place. NZ poetry is a difficult ecosystem because it’s so small, and so it makes things like literary criticism, funding, publishing house aesthetics, feuds, and all the rest of it necessarily complicated, but I don’t have any grand vision, because it’s easy to prescribe changes without really thinking about who ends up doing all the work. Most of our reviewing, podcasts, interviews, reading series, and publishing houses are all a labour of love. They’re undervalued and underpaid (or not paid at all) and saying we don’t have a robust enough criticism scene is short sighted if you neglect the fact that most of the people currently involved are essentially working for the love of it. I’m not saying more funding is the only solution, but it’s easy to complain about NZ’s literary infrastructure without recognizing that most of it is tiring, unpaid work.

A poem from Hera

Ways of making love

Like a metal detector detecting another metal detector.

Like two lonely scholars in the dark clefts of the Cyrillic alphabet.

Like an ancient star slowly getting sucked into a black hole.

So hard we break international sporting legislation, leaving the conveners of the Olympics

with a serious logistical challenge.

You are a denim tree and I’m the world’s fastest autumn.

I am the Atlantic Fortress, and you are General Sherman taking me from behind.

You stride up the cold stone steps of parliament, waving a petition to orgasm.

A lip of cloud brushes the roof of the barn.

The pale trees curve around the eye and back into the brain.

It’s like watching porn through a kaleidoscope.

or a slow wind in a kite factory.

It’s like dogs trying to do it people style, but failing

due to the inflexibility of their anatomical structure.

A cloud of bats float slowly up into your brain rafters.

You roll down my stockings, like the sun peeling ocean from a soviet globe.

I want you in the red shade of a mammoth in the Natural History Museum.

In a seventeenth century field, tilling the earth like flesh tractors.

In the airlock of a space station, my heart shaking like an epileptic star.

Between the plastic sheets of a lobotomy table

because writing poetry about having sex with someone

when you could be having sex with them instead

is the last refuge of the stupid.

It’s like getting three wishes and wishing for less wishes.

It’s like inventing a flag the exact same colour as the sky.

It’s like crying over spilled milk before it’s out of the cow.

It’s like breaking into a field at dawn with a flamethrower

and fireballing the cow so you can get your crying over and done with

and immediately begin adjusting to your new milkless existence.

But loving you isn’t really like killing cattle

no matter what poetry wants you to believe.

The day is a vault the sun has cracked open

money flying everywhere like really expensive leaves

and here I am begging you to come back

as if you were already gone

Simone Kaho writes and performs from the heart. She creates chunks of prose-poetry that offer ironic, never sarcastic, unravellings of the ‘mainstream’ in this country, via cogent excursions into streetlife combined with chilhood reminisence: all via a hugely imaginative fiesta of words. Wry, clever, honest, and unflinching portrayals of the past are actually a post-marginalization broom now clearing/cleaning through the country’s dusty, cobwebbed thrall. I asked her similar questions, as here —

Would you define yourself as a Kiwi poet having a perspective that is different than the ‘normal’/mainstream (i.e. generally Pakeha New Zealander) one? If so, how so?

I didn’t realise I wasn’t mainstream until I got published and assigned to the ‘Pacific writer’ category. Growing up I didn’t fit in with either the paheka cool kids or the brown cool kids. I thought it was the act of writing and being sensitive and poetic othered me — rather than having an ethnic perspective that was different to the mainstream.

Now I’d define myself as different to ‘normal’/mainstream both in my race perspective and as a writer. I’m different as a PI person because I’ve experienced racism from mainstream New Zealand. I understand and have lived the migrant journey of a Pacific Islander coming to New Zealand through my father, coming to New Zealand from Tonga as a teenager in the 1950s. The effect this had on him, his subsequent guidance of me, and the decisions I made as a result of this are common to Pacific migrants and their first generation family. I didn’t realise this until the last few years. Mainstream New Zealand has limited knowledge/understanding of experiences like these — or at least — it distances itself from them. Pakeha are also migrants but it’s not a popular history or accepted identity.

As a writer I think I’m outside of the norm mainly because I’m not particularly interested in exploring form — more drawn straight to the heart of poetry as an emotional and political force. My IIML Masters supervisor (Hinemoana Baker) said to me — do you care about line breaks? — at one of our sessions. I realised I didn’t. She advised me to write without lines breaks or punctuation and this raw voice poured out of me, different to all my other work, more charged and somehow ancient.

I loved it and went with it. It was different to what everyone else in the class was doing. Lucky Punch was written like this, a stream of consciousness style. I’m still working this way.

Also, I am a performance poet. That means sometimes I work with musicians and bring work to life in a way which allows for the relationship between the audience and the poem to include my gesture, tone of voice and volume. The poems I write for performance don’t seem to stand on the page as the ones I write for the page and vice versa. I’m totally fine with that. There are other poets that move effortlessly between page and stage — Courtney Meredith, Tusiata Avia, Sam Hunt, Selina Tusitala Marsh to name a few, but I don’t think it’s the norm.

Do you deliberately concentrate on different and distinct themes, imagery, stylistic devices, and do you ever employ other tongues (words/languages) in your poetry?

I don’t deliberately concentrate on anything when I’m writing. Afterwards when I’m selecting work to develop or keep I’ll see the themes. In Lucky Punch there was a strong focus on plants/my backyard/playing/the natural world, as well as food and flowers. In the work I’m writing now, religious imagery has emerged, birds, topography. I’m not sure how it all ties together yet or if it does.

In terms of stylistic devices, I’m more one for simile than metaphor. I like my poems to live in a real-ish world, where things behave generally as they do in the real world. Magic realism perhaps. The big metaphors I use tend to be more subtle and thematic. There was a theme running through Lucky Punch which said eating meat (especially pigs) is the same as oppression of women.

Alliteration and assonance are important to me, I developed as a writer reading my poems to an open mic (Poetry Live on K Rd in Auckland) once a month or so, and this kept me writing. So there’s a part of me that always thinks about how whatever I’m writing will sound.

Sometimes I use Maori or Tongan words, but I don’t speak either language so it’s limited. I’m working on changing that. I’d like to be able to communicate in three or four different languages and use these in my work.

What would you like to see more of in Aotearoa poetry from your point of view as a poet? In other words is there sufficient recognition, publishing scope, critical space given to (newer) writers who craft their work in ‘different’ ways … ?

I think poetry in Aoteroa is exciting. There are many excellent writers here. And awesome niche publishers, like my publisher Anahera Press, alongside the widely respected University publishers like Victoria University Press, with it’s Award Winning Authors. That said, I have a bug-bear with how PI [Pacific Island] and Maori writers are often talked about and reviewed together as if we’re a little sub-group with commonalities of style and content because we’re brown. I can cite a few examples of this happening to me and other not-white writers and I find it disappointing. It’s as arbitrary as reviewing old, white, male writers in a group — because — they’ll have so much in common … ?

Coming up to the publication of Lucky Punch I was nervous that I was breaking too many rules, and not showing I knew how to write in traditional forms, before finding my own voice. I had great support from Anne Kennedy though, who encouraged me from the get go, after she read my manuscript as an external reader for the IIML Masters assessment. The IIML passed me with a Distinction which showed they were open to unconventional approaches — I think. Kiri Piahana-Wong, my publisher, pursued me for years for my manuscript before I gave it to her. She was patient while I built up the confidence. Hinemoana Baker and Karlo Mila wrote letters of support for Creative New Zealand which assisted the publication of Lucky Punch. Reading them left me buoyant and buzzing.

It’s wonderful to get this support for writing in a ‘different’/unconventional way. I’m not interested in being conventional. I don’t have it in me. If I had to write ‘conventional’ poems to get published I’d never have been published. My spark of creativity fails if I apply conventional requirements to it.

Lucky Punch was widely reviewed which was great. There were reviews in Metro, Stuff, Landfall, RNZ (well, a discussion more than a review), The Poetry Bookshelf, Canvas, Pantograph Punch, and others. The reviews were more positive than I thought they’d be, although less curious and critical of the form — this non-punctuated, prose poem, flash-fiction–style work. There was no particular desire to define the style. It was generally mentioned though not critically probed. I guess the general consensus was that it was successful — whatever it was — which signifies an open-mindedness. That’s cool.

A poem from Simone.

MARY

Mary standing forever like that

her sweet head at the tip.

- Would you define yourself as a Kiwi poet having a perspective that is different than the ‘normal’/mainstream (i.e. generally Pakeha New Zealander) one? If so, how so?

I have been referred to as a Pacific writer (Rotuma, Fiji) living in NZ so in a sense that also makes me a ‘kiwi poet.’ When my father and niece Mereoni picked me up from the Auckland airport eleven years ago, Rotuma and Fiji were tightly jammed in my bags, jacket pockets, and heart. I was coup-fatigued and extremely unsure of what I wanted to do with the rest of my life. But then here was this beautiful land and people showing me its own scars and history, telling me that everything would be okay. NZ has allowed me to yell, scream, curse (yes, I can say fuck), and shake my fist at injustice. My voice is political. I am not sure if this is ‘different.’ Judging from the quality of work in Manifesto, NZ’s first anthology of political poetry, there are a few political poets here. Perhaps none with a Rotuman and Fijian flavour except the amaaaazzing David Eggleton?!

I will write for children who die in damp houses (‘Building Code’). I will write against the beauty industry who manufacture and market skin whitening creams (‘Eumelanin Gorgeous’), and of course, coup crap heads (‘The Paleontologist’). Occasionally, I will untangle myself from these themes of unrest and seek the beauty of nature, friendship, and the stories of children (‘No Frills’). Thank you, Aotearoa, for ‘growing up’ my voice. I am here to stay.

- Do you deliberately concentrate on different and distinct themes, imagery, stylistic devices, and do you ever employ other tongues (words/languages) in your poetry?

I have been asked that question before — do you consciously choose to write about specific themes? Strangely, no. The political edge to my writing developed organically here in NZ. My writing is a reflex action to the affairs of communities from my past and present. Satire, biting sarcasm, dialogue, dark metaphors, and profanity come easily to me. My mother in Sacremento noticed. She does not read poetry but the F-word caught her attention. The F-word is very effective for the evangelism of poetry. Just saying.

In some poems, my mother tongue, Rotuman, has a cameo presence. I find this regretful. Painful. I am a better speaker and reader of Rotuman than I am a writer. Poetic Rotuman language and form, i.e fakpeje, is beyond my English-washed brain. However, I am taking small steps to rectify this. Check in again, in a couple more years.

What would you like to see more of in Aotearoa poetry from your point of view as a poet? In other words is there sufficient recognition, publishing scope, critical space given to (newer) writers who craft their work in ‘different’ ways … ?

I cannot find it in me to demand for more. Compared to the literary infrastructure in Fiji, New Zealand has given me far more opportunities to grow as a writer than than I could have ever imagined. I feel extremely spoilt and lucky here. I keep pinching myself. Did I do something good to deserve all this? I have been very fortunate to have had the support and encouragement of leading voices here (quite easily the cream of NZ poetry) — Vaughan Rapatahana, David Eggleton, Bob Orr, Mary Creswell, Paula Green, Courtney Sina-Meredith, Selina Tusitala Marsh — and Evotia Taumua of Little Island Press, The Meteor theatre in Hamilton and my first friends in poetry in Hamilton, PoetsAlive. Huge arohas from my little creative room in Hamilton NZ.

A poem from Mere.

Time-lapse

this evening like every

other evening at 8.10 p.m

Mapiga opens her mouth

to let the hungry giant loose

he nearly knocks her front teeth out

as he parkours like a grasshopper

into the delicate matter of our brains and

wide-eyed expectations

and this evening like every

other evening at 8.12 p.m

Roald Dahl, Enid Blyton and Dr Seuss

arrive in solidarity to shut her up

this story is not suitable

they say, there is cannibalism

they say, the children will be traumatised

they say

so this evening like every

other evening at 8.13 p.m

Mapiga bares her teeth at

the protesting posse of page pushers

piss off she says

tonight, like every other night

she says, it’s her mouth telling the story

she says, her way

she says

let it be known

this evening like every

other evening at 8.20 p.m

the giant is smoked alive

hung by his entrails to desiccate

and we.

this evening like every

other evening at 8.21 p.m

do.

not.

cover.

our.

ears.

What more can I say? These poets articulate, better than I can summon up, how lucky we are to have such fine artists translating the truth. Redressing, addressing, undressing all number of conventions, both social and literary. In such clever ways. In such inventive fashions. So necessary.

Yes, there is pain here. Rivulets of hurt. Engari he aroha nui hoki [But lots of love also]. All three poets’ writing can make you cry and laugh at the same time. Fine writing does that, eh.

Kia ora.

Here are some inks to each poet:

Hera Lindsay Bird is a poet from Wellington. Her debut book Hera Lindsay Bird was published with Victoria University Press and Penguin UK in 2017, and her chapbook Pamper me To Hell & Back was published by the Poetry Business in 2018. She won the 2011 Adam Prize, the 2017 Sarah Broom Poetry Prize, the Jessie McKay best first book of poetry at the Ockham Book Awards in 2017 and became an Arts Foundation New Generation Award Recipient in the same year.

Simone Kaho is a graduate of the International Institute of Modern Letters (IIML) in Wellington. Noted for her powerful stage presence, she performs regularily at writers festivals, threatres, and live music venues, often with musicians. Simone’s first book, Lucky Punch, launched November 2016 and has been well received by Metro, The Herald, Pantograph Punch, and Landfall among others.

Mere Taito is a Rotuman Islander from Rotuma Fiji, moved to New Zealand in 2007 and now lives in Hamilton with her partner Neil and nephew Lapuke. Her work has appeared in literary journals and anthologies such as Dreadlocks, Saraqa, Vasu (Fiji), Landfall, A Fine Line, Manifesto Aotearoa (NZ), and So Many Islands: Stories from the Caribbean, Mediterranean, Indian and Pacific Oceans (Commonwealth Writers). She is interested in interdisciplinary studies and is keen to see how poetry can be used to teach students critical thinking skills in both science and arts-related disciplines. She currently works at the University of Waikato. The Light and Dark in our Stuff is her first collection.

Feasting in the Skinny Country: Aotearoa New Zealand Poetry