'Poems from the Edge of Extinction'

Focusing on endangered languages via the power of poetry

Kia ora.

The anthology Poems from the Edge of Extinction (Chambers, UK, 2019) edited by well-known English poet, Chris McCabe, was launched at Poetry International, The Southbank Centre, London in mid-October, 2019. He was the MC on this occasion, as well as for several other events during the festival. It is an important collection of poetry written in indigenous languages — including my own, te reo Māori — which are being threatened by dominant Hydra-like languages — like English and to a lesser extent others, such as Mandarin.

My perspective on why languages are under threat:

I have written extensively previously as regards the several agencies pushing English language Hydra-like dominion over indigenous languages across the globe, for primarily cultural-power and pecuniary reasons. Agencies such as the British Council, which continue to press for a worldwide spread of the language into traditionally non-English as a first language communities — so as to seek financial and cultural benefits for Britain. An approach as exemplified in their own words from their December 2019 Request for Proposal —

‘… the organisation is seeking to investigate not merely the direct benefits of the spread of English (in terms of the direct financial benefit to the UK of the provision of English services and the improved skills and life chances of those learning it, both of which are relatively well known and have been widely explored in the past), but in particular the indirect benefits — in terms of greater knowledge of English driving the UK’s influence and attractiveness for trade, and improving the access of those learning English to opportunities, information and culture.’

This is linguistic neoimperialism and a clarion call for world English language dominion at the macro level — as Robert Phillipson puts it — and who once again so very clearly demythologizes the puported ‘advantages’ for those learning it. This hegemony continues unabated, with the consequent ‘linguistic genocide’ — as Tove Skutnabb-Kangas describes the process — of threatened and endangered indigenous tongues, given that Tove was not even allowed to utilise that term at the recent United Nation Forum on Minority Issues in Geneva!)

Back to the anthology:

In Poems from the Edge of Extinction McCabe is determined to provide much-needed exposure to such threatened tongues and at the same time to seek not only support for their survival, but plea for their survival per se.

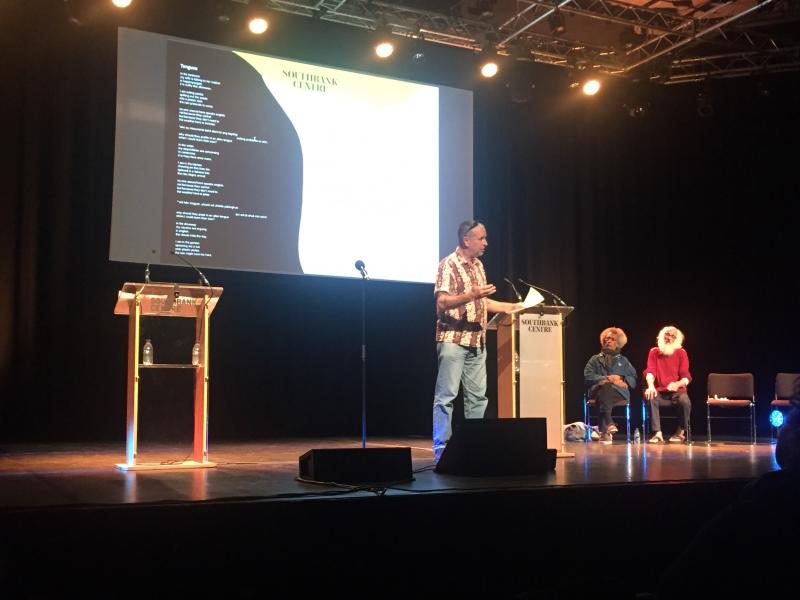

In the collection, there are fifty endangered languages featured and therefore fifty poems representing all continents, as well as translations into English on the facing pages. The poets include Valzhyna Mort, Laura Tohe, Hawad, myself, Nineb Lamassu, Stephen Watts, Shehzar Doja and James Byrne — all of whom were at the launch and who are pictured here —

Laura Tohe (sitting at right), Poet Laureate of the Navajo Nation, also read at the launch. More, she was interviewed by BBC Radio Four.

Valzhyna Mort, well-regarded Belarusian poet (standing second right), and myself (sitting at left) were also interviewed by The Guardian.

In both of the above interviews Chris McCabe was the first speaker. Ubiquitous, yes! I asked Chris (back row centre) several questions about the genesis of this important collection.

Here are his responses to my questions:

1. Why did you see the ‘need’ for such an anthology?

The need for the anthology came about from a number of factors: the interest from a visionary editor, Emma Green, at Chambers publishing; my realisation that an anthology of this kind didn’t exist and the fact that poems were readily available due to public submissions to the Endangered Poetry Project at the National Poetry Library. The stars were all perfectly aligned for the book to come into existence.

2. How did you then go about obtaining ‘enough’ poems in indigenous qua threatened tongues?

I used many of the means available to an editor: researching what had already been published, particularly in the collections at the British Library and the National Poetry Library; reaching out to contacts who had expertise in certain areas of poetry, and scouring the internet for links to poets writing in particular languages. What made this anthology different from other poetry editing I’ve done is how closely I had to work with linguists to find poems in particular languages. There are certain languages that are so little known and understood in the West that it was often the research of a particular linguist who had a visited a place and documented a language that gives us the only knowledge we have of that language. Usefully for me many linguists also have an interest in the oral art of a language and have documented enough examples for me to draw upon in the anthology. This was the case for the Kraho language of Brazil, the South Arabian languages and the Australian language Iwaidja.

3. As a result of this (excellent) anthology, what do you hope to see now?

I see the anthology as a kind of framework for speakers of their language, the poets and performers, to use to tell their stories. We had a wonderful launch at Southbank Centre with readings from poets from each continent. The Endangered Poetry Project remains open for submissions (search Southbank Centre Endangered Poetry Project) through which the library can collect more languages to preserve for future listeners and readers. From that we can programme more events, exhibitions and continue to include as many people as we can in this urgent conversation.

(By the way, we rehearsed rather a lot for this launch! As below — )

I invited Laura and Valzhyna to share their thoughts as to what this anthology meant for their own endangered tongues, Navajo and Belarusian respectively. Valzhyna Mort replied forthrightly —

You ask about my views on the significance of this collection to me as regards to my language. I think that this collection is more significant to the English language than it is to any of the original languages included. An inclusion into a foreign anthology doesn’t change anything for the Belarusian language but hopefully it will give some English-speaker an idea to go and learn a foreign language, and not only a major one, but also one heard less often and perhaps not heard at all. If not learn the language, then read a book translated from that language. I can guarantee that this search would be a significant event for this English brain. When this British person decides to learn this foreign language, they might discover that it’s nearly impossible to find any classes. (I wonder how many Slavic departments in England offer Belarusian as a language to learn. I assume that none.) When this British person decides to read a book translated from Belarusian and published in UK, they might discover that such books are also unavailable. So I hope that this collection will be significant to the English language as it would highlight its many blind spots.

I fully concur with her viewpoint. Poems from the Edge of Extintion is not going to of itself rescue endangered languages. At best it will expose the fact that many of these languages are in severe danger of being completely lost due to Hydra-like tongues (not always English, by the way) and that we as a species do something about this alarming state of affairs. Alarming, as indigenous cultures are epitomized via their languages: we lose the language and we lose vital cultural acumen, insights, knowledge treasures.

As we say in Māori — Ko tāku reo tāku ohooho, ko tāku reo tāku māpihi maurea

My language is my awakening, my language is the window to my soul

Indeed, the more we are pushed and pulled into Anglo English language entrapment, the further we are also lured into learning that dominant language’s distinct cultural tropes at the expense of our own, as Anna Wierzbicka has so well delineated via books such as Imprisoned in English: The Hazards of English as a Default Language. In this 2014 master work, she writes,

‘The goal of this book is to try to convince speakers of English, including Anglophone scholars in the humanities and social sciences, that while English is a language of global significance, it is not a neutral instrument or one that, unlike other languages, carves nature at its joints; and that if this is not recognized, English can at times become a conceptual prison’ (4).

Linguistic hegemony at the micro level also, worryingly, then.

As Laura Tohe writes so eloquently about the vital need to ensure the survival of endangered languages —

2019 the year of the UNESCO’s Indigenous Languages. An important anthology came forth as part of this momentous occasion, Poems from the Edge of Extinction, supported by the Southbank Centre, the National Poetry Library and the SOAS (University of London) and edited by Chris McCabe — the National Poetry Librarian at Southbank Centre’s National Poetry Library. I was honored to be one of the invited poets who gave a reading at Southbank with several poets from around the world.

I should not have been surprised at how many of the poets wrote about genocide as a contributing factor to the extinction of their mother tongues. Growing up and attending US government schools on the Navajo/Dine Nation homeland in New Mexico in the middle of the twentieth century, I was among many Dine youth of my generation to be a witness to the systematic erasing of native identity and languages in schools where our languages were beaten out of us. Ironically, only a generation ago, my father and the Navajo Code Talkers were tasked with the huge responsibility of devising and using a US military code based on our mother tongue for warfare during WWII that successfully eluded the Japanese cryptographers and saved many American lives.

We are now at a point in history where we are faced with the frightening possibility that more languages throughout the world, not just Indigenous languages, will become extinct or diminished. A startling statistic says, ‘One language is falling silent every two weeks. Half of the 7,000 languages spoken in the world today will be lost by the end of the century.’ (Poems from the Edge of the World cover).

My mother tongue is designated ‘vulnerable’ by UNESCO. Working alone at my computer with only the clicks of the keys to keep me company, I wonder about the vitality and longevity of my mother tongue. I am seeing signs ahead and behind me. I think of my grandmother’s teachings about our spiritual connections to the earth. I think about her teachings about water, hair, and the sound of her weaving as part of my childhood. I fear that the Dine worldview and culture will also become extinct along with Dine Bizaad. I feel the urgency to write in my language, the language of The People. Writing one poem at a time like other poets and singers around the world, we are remembering, writing, and creating poems so that our languages don’t fall off the edge into extinction. We need the voices of poetry, translators, and collaborators such as the Southbank Centre to bring this loss to attention of the world through poetry, song, story, and the written word. We also need to make saving our languages a community movement. In saving our languages, we save ourselves.

Again, I completely concur. We want to not merely preserve threatened and endangered tongues as some form of museum archives. No, we must maintain and grow them as living and active.

More, we should also be learning non-English languages ourselves. Why do non-English communities feel as though they ‘have to’ learn the propelled language, English (via ‘international’ testing schemes, imported Western native-speaking teachers, alluring advertisements promising so-called ‘success’ and so on) when we could and should counter the implied arrogance of agencies determinedly mounting such propulsion, by us learning the languages of the non-English communities we live in, we visit, and which we still expect to speak and write in English?

I was also fortunate to participate in World Poetry Recital Night in Kuala Lumpur this year. I performed my own poem tongues as an articulation of my abovementioned point here, while several gifted poets from several countries also read their fine work in their own individual languages. The English tongue did not dominate proceedings and nor should it. Ever.

All power to the Endangered Poetry Project and to all endangered languages everywhere. Poetry is all too often the crux of a culture, originating as it did from oral traditions: in cherishing poetry written in different tongues, we are ensuring our own existential diversities.

Finally, a snapshot of Rapatahana reading at the launch of Poems from the Edge of Extinction, as below. Hawad and Stephen Watts are seated just behind me. Thank you to them and all the others —poets, Southbank Centre staff, technicians, researchers, and especially Chris McCabe — who ensured that this was a momentous occasion.

Feasting in the Skinny Country: Aotearoa New Zealand Poetry