Paddling his own waka: Bob Orr, poet extraordinary

The work of New Zealand poet Bob Orr

Bob Orr has been a well-regarded New Zealand poet for several decades, having eight collections of poetry produced to date, with a new collection due out soon. He is also rather different to so many ‘modern’ poets, in that he has always paddled his own poetic waka (or canoe) in and through his own currents. Oaring across his own ocean, if you will. Bob never completed any tertiary education. He never attended any university ‘creative writing’ classes in an endeavour to craft his poetry ‘better.’ Up until very recently, when he was the 2017 University of Waikato Writer in Residence, he eschewed any applications for literary grants. He rarely, if ever, uses a computer to write with or on — he doesn’t even have an email address. Indeed, he continues to write with an old style ribbon-fed typewriter. Bob Orr is a bit of a Luddite — all of which ensures that his stream of poetry flows deep from his heart and mind and is never obfuscated by the trends, tropes, and trivialities of the latest poetic fad. Like another key New Zealand poet, Sam Hunt, Bob Orr has always remained a people’s poet, by which I mean, a writer who keeps it simple, who never overreaches into pretentiousness and amorphous cleverdickism.

Born in 1949 and living in the one-wink-and-it’s-gone Hoe-O-Tainui, in a primarily agricultural province Waikato, Bob spent his adult life mostly in Auckland, working as a seafarer on the Waitemata Harbour and the Hauraki Gulf. His poetry reflects his maritime, water-bound vocation and visions. At present he is living in a tiny settlement named Te Mata on the Thames Coast — close to the tides, in sight of the waves. Ever ruminating on the forces and fissures of Nature, his poems are very often brief, succinct, tactile, visceral, potent. As here —

Mexico Hat

Island of wiry grass and

oyster chapped rocks

scarfed by a shoal

of sea-rippled brown sand

at the bottom of king tides

to Te Mata

Exposed to prevailing south westerlies

maybe not desirable property

but through wave-swung days

a seagull has cobbled together a nest

from frayed net and twine

a twist of long-line and anything else that unravels

Mexico Hat

a hard rock on which to survive

but for two mottled eggs beneath a seagull’s warm down

it’s

paradise.

I asked him a few questions, and his responses were — typically — brief, but cogent and to the point:

Would you define yourself as a Kiwi poet having a perspective that is different than the ‘normal’/mainstream (i.e. generally, Pākehā New Zealander) one? If so, how so?

I feel that it is now almost impossible to define a ‘mainstream’ perspective with regard to NZ poetry. As I see it the whole scene is now incredibly diverse — ranging from ‘poetry slams’ and Instagrams to the more traditional outlets such as Poetry NZ and Landfall. The university presses which once published mostly middle-class Pākehā poets now reflect the diversity of cultures and ethnic groups creating poetry in Aotearoa.

Do you deliberately concentrate on different and distinct themes, imagery, stylistic devices and do you ever employ other tongues (words/languages) in your poetry?

My themes change according to my circumstances. I write about love when I’m in love. About death when I’m confronted with death. About cities when I’m in cities. About the sea when I’m by the sea. In other words I like to write directly about what my senses and emotions convey to me. I am sustained as a poet by the natural world — its simplicity and its mystery. Mostly I use words that are found in everyday speech. [Rapatahana stress]. In some recent poems I have started using Māori words and phrases, especially in those works concerned with my childhood and ongoing links to the Waikato region where I was born.

Bob is also a popular poet, whose name is recognised and ratified beyond critics and commentators. He strikes a chord precisely he is transparent, honest, clearcut in his lines. If he is in love, he says so. If he is awed by a physical spectacle, he encapsulates his capture. He draws out parallels between people and items, we don’t necessarily scan, while he can also describe a person to a tee, without too many words. His koan-like poetic humility is the mirror image of the man. He will never tell you, for example, that in 2016 also he was awarded the Lauris Edmond Memorial Award for Poetry, a prize given biennially in recognition of a distinguished contribution to New Zealand poetry. Richly deserved, I reckon.

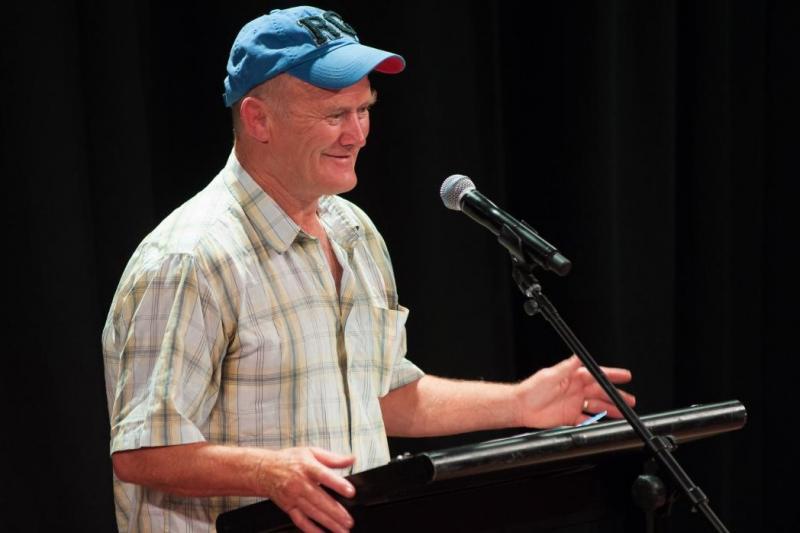

Bob in action, Grey Lynn, Auckland, 2014.

A couple more poems by the master navigator:

|

An Ordinary Day in Hamilton With her middle-aged spread |

Koromiko There’ll be snow on the Kaimais |

What would you like to see more of in Aotearoa poetry from your point of view as a poet?

Poetry no longer seems to be taught much in schools these days which is I believe a great shame. In my day poetry was taught at both primary and secondary school levels demonstrating that language had possibilities as an art form as well as functioning at the more prosaic level of everyday communication.

What’s new for Bob Orr?

I have recently completed a new volume of verse. One Hundred Poems and a Year which will be published by Steele Roberts in the near future.

[Bob also is a New Zealand writer of tremendous historical importance, in that he was there last century, at the forefront of exciting new Auckland-based poetic momentum, the so-called Big Smoke generation: he is a survivor, given the departure of several of his peers.]

Tell us about your encounters with several outstanding Kiwi poets from your many years spent seafaring in Auckland port.

Before I arrived in Auckland in 1968 most of the poetry I’d read was by English poets — some of whom had died centuries earlier. Suddenly I was hearing living poets like James K Baxter and Hone Tuwhare, David Mitchell and Mark Young. Those were exciting times. Later when David Mitchell set up his Poetry Live evenings I was able to hear the works of many other writers, some of them like myself still finding their ‘voice’ and grateful for a venue to test new work. David Mitchell himself was a stunning reader of his own work which brought into play influences dating from the Elizabethans to the Beat Poets and Bebop jazz.

There is one further precious metal being mined from the ore, that is the mahi (work) of Bob Orr: his empathy with te ao Māori [the world of Māori]. In many ways, he captures how Māori pay homage to Nature; to whānau or family; to our mystical embrace of the profound currents implicitly running and rebounding everywhere; to maintaining grace; and to sanctity and sacredness. As in a final, rather beautiful homage here:

Hawaiki

My first

university

the freezing works

at Horotiu –

my first professor

a tohunga

in white overalls and

gumboots

who worked

on the boning floor.

One evening drinking

beer

as the setting sun

was turning the Waikato River red

in the course

of our conversation

he told me

he could trace his whakapapa

back to Hawaiki.

I enquired, ‘Where is

Hawaiki?’

His answer

can’t recall.

On the other side

of the street

beneath the bloodlines

of an evening sky

a boy on a bike

chanted,

‘āke

ake

ake.’

[tohunga — expert, priest; āke ake ake — forever]

Tēnā koe Bob Orr. Ko he taonga koe.

Links:

An outstanding, earlier piece in Metro by Tim Wilson entitled “The Outsider,” sums up Bob Orr so well.

Here on the NZEPC site, Bob Orr reads his own poems.

A happy chap, a damned fine poet.

Feasting in the Skinny Country: Aotearoa New Zealand Poetry