'Wild Honey, Reading New Zealand Woman's Poetry' — Paula Green

Vital publication about New Zealand women poets

Wild Honey: Reading New Zealand Women’s Poetry (Massey University Press, 2019), by Paula Green, is an important book.

Indeed, it is a key book in that there has not been such a comprehensive overview of the place, the role, the significance of woman poets in Aotearoa New Zealand previously. Accordingly, it starts to correct the historical imbalance between the recognition and respect accorded male Kiwi writers per se, and that accorded women writers, who struggled throughout the twentieth century especially, to be published at all. I have written at length about the rampant sexism in Aotearoa New Zealand’s literary scene, as in a 2017 Pantograph Press piece, while to their credit Pantograph Press continue to stress this imbalance between primarily WASP male writers and women.

Paula Green’s huge (571 page) and hugely positive and celebratory paean to women poets counters such sexism via the articulate and ever-appreciative tone set throughout. A tone that harmonises with the title: this book is a honey dip in that it is not to be read in linear fashion, but is sweetly designed to continue to go back into over and over again, on any page. A tone that Paula has always maintained via her invaluable New Zealand Poetry Shelf pieces over a number of years — including toward male poets!

And let us not doubt that the gender imbalance between respect, recognition, and fiscal reward accorded male writers in Aotearoa New Zealand to that of women (incidentally also to Māori, Pasifika, Asian, LGBTQ authors) continues today. As just one example, given that it is a little dated, is what Lyn Barnes (2015) wrote regarding the state of play pertaining to journalism here:

… a marked discrepancy between the number of females enrolling in journalism courses (76% on average between 2005 and 2015) and the numbers of females in newsrooms. The statistical analysis of the 2013 data indicates that males are more likely to be employed as print journalists, to earn more and achieve senior positions. The chasm between the number of female students and working print journalists reinforces the need for more comprehensive data gathering to monitor gender patterns in the New Zealand media industry and address this inexplicable gap.

Eleanor Black (2015) further excoriated this palpable gap with regard to fiction, while Janice Freegard (also 2015) articulated so well this sheer difference regarding ethnicities (especially) and gender within New Zealand publishing.

Paula Green now gifts us her encyclopaedic exegesis, which goes a considerably long distance to not only further illuminate this gender gap, but also to close it up once and for all, by revealing both the extensive array of gifted women poets and also their huge range of approaches to poetry writing. Yet, as she notes in her introduction, “I have been hard-pressed to find a New Zealand poetry anthology that gives equal representation to women and men, although the situation has improved immensely.” This book — which incidentally was shortlisted for the 2020 Ockhams Awards for General Non-fiction — is long overdue.

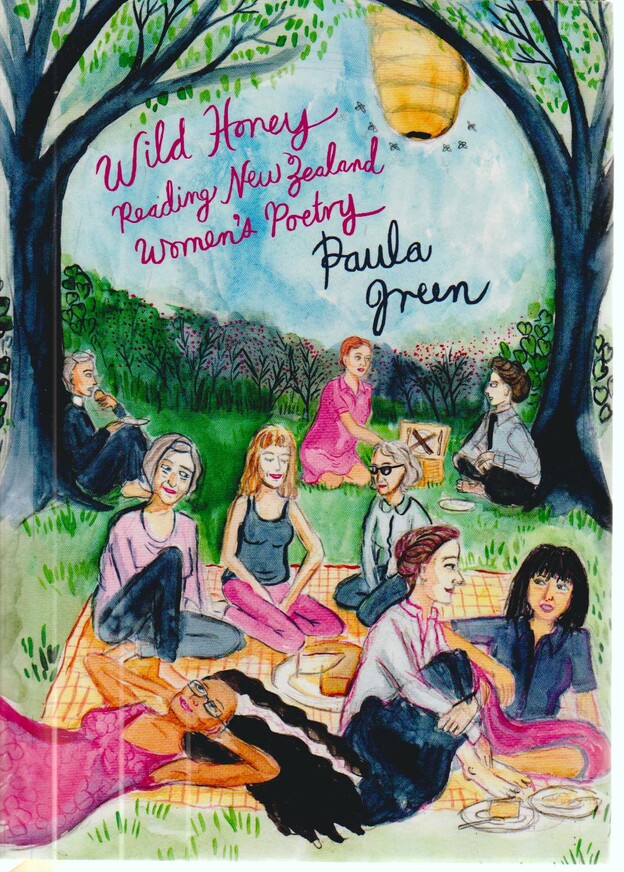

Green constructs for us a house, divided into several areas, ranging from The Shoe Closet through to The Mantelpiece, and travelling outside the immediate abode to The Garden and The Countryside, in her panoramic study, which is less an academic treatise and far more a love affair of percipient delight. In her own words, “The book is neither a formal history nor a theoretical overview of New Zealand women’s poetry, but is instead a celebration and engagement with poems throughout my readings.” Sarah Laing’s distinctive illustrations serve to make the repast even more tasty.

Green lays as The Foundation Stones of our women’s poetry, Jessie Mackay, Blanche Baughan and Eileen Duggan and goes on to discuss 198 others, often introducing us to poets who have been shunned, underrated and — interestingly — not even known about.

I am immediately reminded of the work of Hirini Melbourne and his concept of whare whakairo, or a carved meeting house, whereby everything in and about this construction fits into and lends support, stability and splendour to every other component. The parallels are manifest. Granted that I am transposing women poets into his words, however Melbourne’s description of te whare whakairo rings out as so similar to Green’s own kaupapa in Wild Honey, namely, “The whare whakairo is … a place of shelter and peace. It is a place where knowledge is stored and transmitted and where the links with one’s past are made tangible … [it] is a complex image of the essential continuity between the past and present …” (Melbourne, 1991).

Green’s poetic mansion echoes this concept and her construction is not only strong and structurally sound, but symbiotically intertwined amongst all of its components. More, the construction is not compartmentalized: women poets wander from room to room and crop up throughout the book, even to the extent of their letters to one another being incorporated in the text.

Green does admit that, “I have had to overlook the rich history of women’s waiata and poetry in te reo” (a mighty tradition which Melbourne stresses), yet in this acknowledgement she affirms that there are still rooms to add, “… my house would have needed extensions to cover the missing poets and themes.” To her continued credit, she continues to escalate the edifice via her frequent Poetry Shelf postings and updates.

Paula presents her book below!

I asked Paula several questions.

1. What prompted you to start this mammoth project/write this book?

When I finished my Italian PhD on women writers, I dove into poetry published into Aotearoa. I walked out of the academy knowing I needed to create a different writing life for myself. In my doctoral thesis I had been asking what drove the pen that the Italian women held. Back home I was drawn to the way women poets had been kept in the shadows, misrepresented, undervalued by the white men creating the fledgling canon. I wanted to shine a light on women poets and show there is more than one way to write about poetry. I also knew I would not compromise the book to meet academic expectations of how a critical book ought to behave.

2. Why did you structure your book as a house, complete with foundations and many rooms as well as exterior appurtenance?

I liked the idea of reclaiming the domestic and refreshing it. Women have had a history of writing from the kitchen and have been denigrated for doing so. So I wrote this entire book at the kitchen table looking out at the bush and the birds, the wild west-coast sky. I wanted to build a home for women’s writing that moved beyond walls and windows into the wider world. I wanted to show that women can and will write anything, and in a universe of ways.

3. You throw light on several underrated, indeed unknown, poets who never received a “fair go” as regards publicity and repute — a poet such as Lola Ridge for example. Did you discover these poets during your research, or did you already know about them? Are there others whom you have not yet mentioned, perhaps?

I discovered some women such as Blanche Baughan and Jessie Mackay through their fleeting appearances in early anthologies. Others I discovered in the archives or through the interest of other writers (Michele Leggott on Lola Ridge and Robin Hyde). There were so many early women who were publishing in journals and newspapers (it was the thing to do), but I drew a line at exploring these. That is a whole other book! I did look through physical library shelves (I have loved doing this since childhood) — I discovered the poetry of some of the first Māori women published in English such as Evelyn Patuawa-Nathan.

4. It is 2020 now. However, even so, are New Zealand woman poets receiving as much attention, publication, critical acclaim as their male counterparts yet? Even given the recent VUW Press focus on publishing woman poets who are certainly unafraid to castigate men or at least ignore their work, is there a “fair go” for woman poets in the whare of New Zealand poetry?

Hmm. Janis Freegard has done an annual survey of the inclusion of women in Aotearoa literature and men still seem to come out better. I have yet to see an anthology where women match the men and there is greater room for non-binary writers. However publishers are definitely embracing the poetry of women. I decided not to include my stockpile of negative men anecdotes in Wild Honey. I didn’t want to give space to the times I, or other writing women, have been silenced or misrepresented or bullied by men (as recently as a few years ago for me). Instead I wanted to offer my voice and to privilege the voice of women. I do see a groundswell of young women writers, though. If you look at Starling, the online journal founded by poet Louise Wallace, I am hard pressed to find many young men poets. When I survey these exciting new voices I welcome the infectious diversity: what is written, how it is written, who is writing, where they are writing from. There are many kinds of melodies, politics, personal revelations at work.

So much to say on this matter: you are still more likely to see someone writing about how a young woman poet looks than how a young man poet looks. Domestic writing is still cited as tedious and boring. We still have more men who have won the Prime Minister’s Award for Poetry than women. More men have been NZ Poet Laureate. After several men in a row, I heard people mutter that a man had to follow Selina Tusitala Marsh. Can’t have two women in a row. That seems to me to be unconscious sexism. This is a complicated subject and the need to keep the conversation going and the spotlight shining is still essential.

Last year I did Wild Honey events throughout Aotearoa where women came and read, and I have never experienced anything like it. Such a strong feeling as younger and older writers made connections, different kinds of voices were heard together. I felt like I was holding something enormous that I created but that it got bigger than me as so many women told me what the book meant to them. It was overwhelming and it was wonderful.

5. Do you envisage a follow-up sometime in the future so as to mention poets like Ya-wen Ho, Marino Blank, Laurice Gilbert, Tracey Slaughter, Wen-Juenn Lee, Aiwa Pooamorn and so on … ? (I guess the list becomes endless.)

There are so many glorious women poets that did not make the book — I had to ditch some rooms and objects — and some women missed the cut as their books came out when I was nearing completion. I had had to set rules for myself — one being the poet needed to have published a book or chapbook. I found my list of missing women heartbreaking and would wake in the middle of the night crying as I felt like I was closing doors and windows when I wanted my book to open them. Niki Lindsay Bird is a poet whose work I admire enormously who didn’t make it. I am really drawn to the writings of Ruby Solly.

Poetry Shelf is a place in which I can give these missing women attention, especially at a time when poetry reviews are such an endangered species. But even then I can never give presence to all the wonderful poetry published in New Zealand.

Wild Honey took so much love and attention on my part, I felt completely empty, and in the book I suggest it is over to someone else to write another version. I said, too, that I would love to see a Māori or Pasifika woman write the next one in order to offer different paths, prisms, choices. I have different things I feel compelled to write now, smaller, intimate, secret, and I don’t know if I want them published. My writing motivation is the process itself, and the force that drives my pen is love.

Paula Green is — of course — a very well-regarded poet herself. I think that an apposite way to finish this commentary is one of her fine poems, addressed as it is to another eminent New Zealand woman poet:

Letter to Jenny Bornholdt

When I was contained by bed

I lived in the airy poems,

and the wonder of the ‘French Garden’

each day was a tonic.

A small plant sprang up

in its rhyme

and gave off the scent

of melancholy

a sweet joy

then basil or garlic.

Sometimes in my wanderings

in the muffled sky

and the steep slopes of your poem

I pictured myself writing.

— from The Baker’s Thumbprint (Seraph Press, 2007)

The poetry house pictured below is that of one of Aotearoa New Zealand’s leading — yet, for years, neglected — women poets, Robin Hyde. I am certain there will be many more such fine mansions for future generations to visit and enjoy from now on: women’s poetry here is indubitably even further established because of Wild Honey.

Thank you, Paula Green.

Feasting in the Skinny Country: Aotearoa New Zealand Poetry