Three southern gentlemen poets

David Eggleton; David Howard; James (Jim) Norcliffe

Kia ora ano.

I would like to feature in this Commentary Post, three South Island (N.Z) gentlemen poets — Jim Norcliffe; David Howard and David Eggleton, all of whom I know and all of whom would without doubt be seen as among Aotearoa — New Zealand's leading mainstream poets. Mainstream, essentially, as they are English language poets all and generally speaking, would not be seen as 'experimental' poets, given David Eggleton's earlier more varied performance ethos and activities, among them as recording artist. All three are professional poets, by which I mean they have had life long careers as published poets and that they take the job of being a poet very seriously, for which I admire them.However, such is the state of being a New Zealand poet, very few poets there could ever be employed in full time 'permanent' paid positions. Indeed, there is even less funding available these days, as James Norcliffe so cogently laments, 'I know the liberal arts have been starved for funding in the universities and English departments have suffered as much as anyone. Creative New Zealand is starved of funds and government support for the arts is scandalous...'

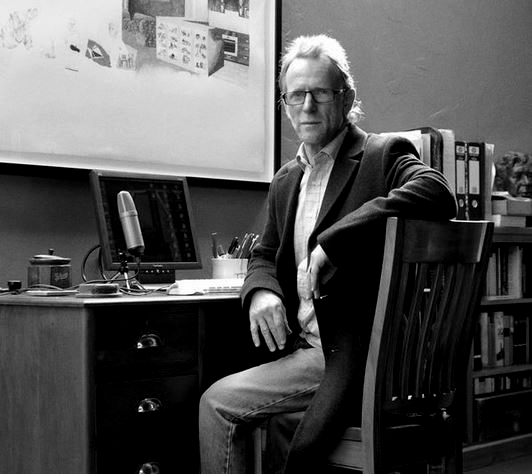

David Howard from Purakaunui nr. Dunedin

All three have also been instrumental in setting up or editing two of New Zealand's leading mainstream poetry magazines, South Island both — Landfall or Takahē — and all three at some stage in their long-running poetic careers have been Robert Burns fellowship holders at the University of Otago in Dunedin — one of the country's most prestigious poetry mantles; as well as winners and owners of a welter of other awards, fellowships, invitations to overseas poetry festivals and so on. All three have featured somewhere in the confused gamut of anthologies irregularly compiled in the land compiling New Zealand's 'best' poems. All three, then, are fimly in the Centre, even if they might not say so themselves.

And, without doubt also, all three are southern gentlemen, as well attested to by my own individual dealings with each of them. David Howard, for example, gifted me a copy of his relatively recently published collected works (The Incomplete Works) at a launch of my books at Kilmog Press HQ in Dunedin, whilst David Eggleton and Jim Norcliffe have hosted me in their respective hoomes, as well as positively reviewed and penned cover blurbs for my own books of poetry.

Poetics, South Island Poetry and Publications

So let's start with a poem: this one by David Eggleton, who was a little wary of stating a definitive poetic in Aotearoa and instead preferred to offer it in his own words, 'No, that's not a question I ask myself. Theories are nebulous entities: customized myths made fit for purpose and driven by emotions, acknowledged or otherwise. In an age dominated by scientific pragmatism, the devil makes work for idle minds. They order these things better in France, or they used to; now the pointlessness of it — 'a poetic' — has become more obvious, or a matter of agendas, and we know where they lead.'

David Eggleton from Dunedin

Moa in the Matukituki Valley: A Cento

Mountains crouch like tigers, resentful,

and Moa's seeking eyes grow blind,

upstream, wading towards the taniwha.

Moa's a strange bird, old and out of time,

driven from the bush by the Main Trunk Line.

The world is divided between Moa and the rest.

Moa, you are not valued much in Pig Island,

though it admires your walking parody,

and poor saps poeming to the trees imitate your malady.

Moa's a good keen citizen, very earnestly digging

in puggy clay at the bottom of the garden for a worm.

Moa cracked a word to get at the inside.

Here come the clouds, Moa, puffy like breasts of birds.

Blue's the word for the feeling, Moa, as you levitate,

homing in on living here with your little flock of sheep.

But, Moa, if you feel you need success,

and long for a good address, don't anchor here

in Pig Island, take a ticket for Megalopolis.

Moa's solitude: pacing along an empty beach,

creating in his head a plan to get at the wild honey.

The door flaps open like a wing, Moa enters without knocking.

Not understood, Moa moves along asunder,

losing the path as the daylight creeps

with shadows of departure. Distance looks Moa's way.

Now Moa's there, stoutly bringing up the rear.

Brothers, we who live in darkness, sings Harry,

let us kill Moa, push him off.

Beware the Masters of Pig Island, Moa,

and skedaddle for it from Skull Hill:

they'd make if they could a bike seat of your beak.

Upon the upland range stride easy, Moa;

surrender to the sky your squawk of anger,

and at the door of the underworld, pass in peace.

[NB. Pig Island is the South Island of New Zealand, although Paul Millar would have it as all of the country, whilst Harry could also refer to another James K. Baxter trope — Harry Fat — politician, bureaucrat, censor. Of course Baxter wrote Poem in the Matukituki Valley. Eggleton is having some fun here, given the pointed barbs of this Baxterian cento and the potential and actual poetry schisms personified within, whether imported from afar or from much closer to home.]

James Norcliffe from Christchurch

James Norcliffe also refrained from any definitive assessement of an Aotearoa poetic, whilst his summation of 'the current scene' follows, 'Am I happy with the present situation? I find that a puzzling question. Aspects of the present situation – whatever that is – I find troubling. I’m not sure what the situation currently is in schools having been out of them for fifteen or so years, but I suspect — given the Gradgrind approach to education of the current government – that the teaching of poetry if it still exists is dire...Having said that, poetry lives. Each year Tessa Duder and I edit ReDraft, a publication that brings the very best of young New Zealand (13 – 20) writing together from 100’s of entries. We continue to be blown away by the sheer quality and brilliant originality of the best poetry...'

'Cliques and personalities? I don’t think so...I know there have been arguments (pace Patrick Evans) about the influence of the Victoria University Institute of Modern Letters – the so-called Bill Manhire School and the so-called Manhire Babes, but I don’t buy them, largely because of the individual and wide-ranging nature of the voices found in the VUP productions... The current scene as you [Rapatahana] suggest has such a lot going on in some ways and the net and electronic publication has facilitated this to some extent, countering the starvation of funding and resources for paper content.'

Norcliffe sums himself up cogently, 'Perhaps I am just an easy-going, sanguine sort of person and shy away from argument.' I can vouch for this personally because last century I was teaching in Brunei Darussalam for several years and at one stage a bearded chap, Jim Norcliffe, a sort of mellow younger Santa Claus, was my Head of Department and I have kept in steady contact ever since. Indeed, some of his poems found their way into Under the Canopy, the first ever English language poetry collection in that country, which I instigated and co-edited with another old mate, Alan Chamberlain.

So, where is any Aotearoa poetic, or is it another moa, dead in the fiords somewhere? Did it, can it even ever exist? For David Eggleton, any such beast was decimated during the 1980s, 'Now there were no fixed points, just a series of networks...The notion of a common, simple voice was rejected in favour of multiplicity and the partisan poetic.'I will leave it up to the more direct and outspoken David Howard to investigate further, stressing here that I tend to concur with most of his pointed points soon to follow. But before I do so, it is imperative to point out that Howard inaugurated the long-surviving South Island poetry magazine —Takahē. Indeed Jim Norcliffe stresses that, 'Takahē was the child of David Howard. He had been poetry editor of a magazine called Cornucopia in the late 80’s and essentially took over and renamed the magazine, bringing Sandra Arnold as short fiction editor with him.'

David Howard, 'As both an editor and a writer I have a strong interest in the ability of language to modify external, shared reality...The opening poem of Takahē 1 (Spring 1990) was the American Sheila E. Murphy’s ‘The Professional Poem’...I chose to open with this poem because it was already clear to me that Bill Manhire’s love affair with Robert Creeley and the New York poets, conducted since 1975 inside a curricular architecture adopted from the Iowa Writer’s Workshop, would set itself up as the coaching school for those who wanted to ‘play the game’. And so it came to pass – but not, alas, away. In 1997 Bill offered the first Masters in Creative Writing and in 2000 his House of Usherettes rebranded as the International Institute of Modern Letters...I preferred to ‘do otherwise at great risk’ and hoped, by launching Takahē with the editorial support of Sandra Arnold (who named the journal), to provide a meeting place for disparate but committed writers, writers whose styles were as diverse as their homelands.' Howard goes on to state that, 'I left after #16 because I did not want to become someone whose reading tastes had codified into editorial prejudices, acting as a bottleneck rather than a conduit.'

He Takahē — another rare South island bird, that almost died out. Will it again?

It was then that Norcliffe took over as poetry editor, in his words, 'I began to contribute to the newTakahē and eventually shared poetry editor duties with Bernadette Hall for a spell and then took over as fiction editor. Later still, I took over from Bernadette as poetry editor and remained as such for several years before in turn passing on to Siobhan Harvey. In that time, Takahē has progressed from a kitchen table operation to the attractive, colourful perfect bound journal it is today. I did enjoy this time and the Takahē team and I very much liked Takahē’s ethos – eclectic, not beholden to any poetic dogma and increasingly able to attract a wide range of voices from New Zealand and beyond.' Incidentally, Norcliffe also curates the weekly Christchurch Press poem page, a duty he also took over several years ago from Bernadette Hall. And he chairs the Christchurch Poet's Collective, started also, incidentally, by David Howard. He — Norcliffe — is a busy man.

Let's return to Howard's more acerbic approach, 'Over the last two decades it is depressingly easy to map the territory of prejudicial readings within our criticism...Looking back, I see that there are any number of New Zealand poets who follow what American poets do – the governmental agency Creative New Zealand even funds locals to attend Iowa– but the merit of copying from the dominant, if ailing, economic power escaped me when I was editing Takahē and it escapes me now. Reputation often comes down to who is the best mimic. Why assume that the stamp ‘Made in America’ is a mark of quality rather than a geographical description? Surely readers want a different perspective, a new world rather than the New World regurgitated in talky non-poems?'

Thus this, his following poem:

ALWAYS ALMOST, NEVER QUITE

at home

in the interpreted world

— Rainer Maria Rilke, Duino Elegies I

1

Saying is only one way of doing, it is

a narrow cloth for a long table.

However hungry, everyone must leave table

without much thought for the stained cloth.

Anyway, songbirds are followed by birds of prey;

both balance at the end of the pier.

The rowboat waits – that is what it was made to do

so it won’t get impatient, it won’t

chafe the rope that will soon be thrown

over. Always almost, never quite

a bullock hauls itself out of estuary mud

to shuffle through the Milky Way.

2

The moon showing itself

slowly, it showed us

how to grow. Tonight a jazz singer takes light

away, it waits in her diaphragm and her pelvis.

Faithless, the sea leaps

off one rock, onto another. Jetty ropes tighten

around a boat called Billie’s Holiday.

It is too dark for shadows, the moon

a blood-blister on the horizon’s upper lip

hard, so hard.

3

God, night is more merciful than day –

it allows those chosen to dream

things are otherwise, but things.

Learn from the violin’s darkness, its gloss

a note’s decay – at the top of the peg box

a scroll without names…

4

All we have is fragments of what was

Times Square, ordered according to size – always

we saw the biggest first, even before

the crash. We thought the biggest more

real. Those stones used to be the leader’s statue.

We throw them, hoping when they hit

home, we’ll hear our name and remember.

5

A minor god’s cart toppled –

the iron bands of a barrel broke

loose, the darkest wine poured over earth.

‘Our thoughts are always elsewhere.’ (Montaigne)

There, in the ruins of popular song

and the colour of a girl’s cheeks, a girl

who reads poetry in private because love is a secret.

6

Morning’s cornstalk topples into that charcoal pit

afternoon. She slept beside the river, dreamt

men were happy, their women were not

unhappy. You read this because I have gone

ahead, there are no banks only swirl

and one Amazonian lily, open

so the sky can fall into it night after night.

'My poem ‘Always Almost, Never Quite’ was an invited response to the declared theme of the Going West Festival, 2012...an intimate festival where it is possible to talk with all the presenters...But in the monotonoverse of larger literary festivals, which are peppered with touring almost-celebrities, what most presenters ‘know is special/ Pleading.’ Discussion is in the service of admiration rather than discovery.' [I will look further at this particular festival, further down the track of pursuing the Other in New Zealand poetry.]

Howard next waxes particularly philosophical and explosively erudite; remembering that he is also a professional pyrotechnician by trade, 'If everything already exists, including the poem I’m trying to write, then composing is really transcription, a privileged kind of listening. As the Czech poet Jan Skácel put it:

Poets don’t invent poems

The poem is somewhere behind

It’s been there for a long long time

The poet merely discovers it.

'I learnt this when I heard Arapera Blank speak, in 1989, as I was planning Takahē. Discovery is predicated upon listening, which is the common name for inspiration. That's because I view poetry as a way of knowing; it is primarily an attempt to understand rather than an aesthetic endeavour. Incidentally, this means that I treat contemporary notions of hierarchy...and associated technical models – principally the conversational ironic – as fluorescent red herrings. And a dialogue with the dead, which I welcome, does not presuppose reliance on authority.While I expect to hear something whatever I hear will be unexpected; if all I hear is the voices of past poets then I am, literally, at a dead-end'

David Howard, then, has most definite views, which I believe he will extrapolate on further in an impending series of commentaries with Jacket 2; staunch and rather intense views about philosophical and geographical ruptures and rivalries in the New Zealand poetry landscape. One of these is the perceived North-South divide in terms of the imbalance in funding granted the latter literati, despite the status of the press and the poets in the Mainland.

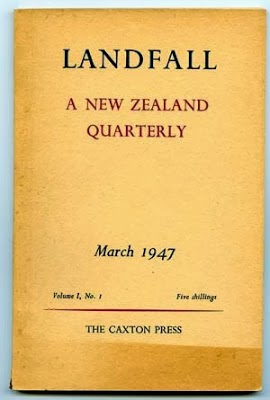

David Eggleton is Editor and I guess, chief gatekeeper for Landfall and its more recently-arrived cousin Landfall Review Online, New Zealand's most prestigious literary publication, where he is bombarded by submissions of poetry, prose and visual art. An expatriate Kiwi poet ally in Hong Kong, Blair Reeves, once expressed amazement that I (Rapatahana) had managed to have a poem placed in Landfall, when he said,' Getting a poem in Landfall,' is bloody hard.' Blair, by the way, also professed kinship to yet another fine Dunedin poet, Richard Reeve. Not to be confused with a further Dunedinite, Trevor Reeves, who has to be mentioned here as inventor of Caveman Press, Cave magazine and the first New Zealand online poetry site, Southern Ocean Review, all some years ago now. Everything is all-connected in the end. Especially in the world of Aotearoa poetry.

David Eggleton is Editor and I guess, chief gatekeeper for Landfall and its more recently-arrived cousin Landfall Review Online, New Zealand's most prestigious literary publication, where he is bombarded by submissions of poetry, prose and visual art. An expatriate Kiwi poet ally in Hong Kong, Blair Reeves, once expressed amazement that I (Rapatahana) had managed to have a poem placed in Landfall, when he said,' Getting a poem in Landfall,' is bloody hard.' Blair, by the way, also professed kinship to yet another fine Dunedin poet, Richard Reeve. Not to be confused with a further Dunedinite, Trevor Reeves, who has to be mentioned here as inventor of Caveman Press, Cave magazine and the first New Zealand online poetry site, Southern Ocean Review, all some years ago now. Everything is all-connected in the end. Especially in the world of Aotearoa poetry.

Eggleton most certainly is an articulate defender of the Landfall faith. After initially granting me a potted history of New Zealand poetry from Jim Baxter and especially from that episteme-shaking decade of the seventies, Eggleton has this to say, 'The quarterly Landfall and the more erratic Islands competed throughout that tranced decade of the Seventies to be the central litmag voice of the orthodoxy, while other, more arriviste, publications continued to “boldly bring up the rear” — in R.A.K. Mason’s deathless phrase...By the Nineties, Landfall as a national literary journal, appearing twice yearly, found it had strong competition in the Victoria University Press-published Sport literary journal, which used a similar format and also began appearing twice yearly; a situation which persisted until around 2010, when Sport suddenly became more erratic, appearing once yearly. Landfall, meantime, after a peripatetic existence, appearing out of Auckland then Christchurch again, became established once again in Dunedin in the late Nineties, where it was published by Otago University Press. After periods with two long-term separate editors — Chris Price and Justin Paton — up to 2005, followed by a revolving door policy on editors, I was appointed Editor of Landfall in 2010, by the Otago University Press publishing committee; and I am also responsible for Landfall Review Online.'

He then proceeds to promote further, 'Landfall has always been the plucky little magazine that could: a prime mover in presenting notions of who we are, where we are. Itself a mythic piece of the nation’s cultural estate, its heritage is that of New Zealand’s finest literary, social and cultural magazine — one of broad scope, unaligned to any particular school, faction or grouping, and one which, in the past, over the years, has published just about everyone who was anyone in New Zealand letters. Established by poet and writer Charles Brasch in 1947 as a national arts periodical, and first published by Denis Glover's Caxton Press in Christchurch, Landfall is now New Zealand's longest-running arts and literary journal. Founder Charles Brasch was a visionary, a very clever promoter of messianic Modernism, who handed down the blueprint, the focus, the vision, which has been more or less maintained by all the editors since.'

He goes on, 'Currently Landfall polices no orthodoxies and proclaims no diktats, but instead is a broad church of both the canonised and those unlikely to be canonised anytime soon...Landfall remains the nation's liveliest and most important literary magazine...Landfall works hard to maintain its pre-eminence...Landfall as a concept has shown a remarkable capacity to refresh itself, to reinvent itself. This it continues to do, even as ideological notions of nationalism versus internationalism, of cultural cringe versus cultural assertion, have moved on from fixations on melting pot assimilation to awareness of latter-day multiculturalism and global diasporas...' Eggleton then talks extensively about the online Landfall Review Online, stressing that its format will act as a counter, 'at a time when the world is in a state of constant technological revolution, involving shifts in reading habits, shifts in audiences, shifts in market expectations'

Finally he stresses the fact, 'It is intended that the LRO commentariat maintain the dignity and authority, the measured approach, the essentially sober [my stress] tone that Landfall has endeavoured to pursue offline.'

Landfall and Takahē are, then, most firmly affixed as axes of the New Zealand poetry centre, given the recent plummet in funds, itself partly brought about, of course, by less print readership, more online parley and much more experimentation in presentation and live performance.

Speaking for myself, I don't envy David his task as editor. Not just because of the unstaunched inundations of submitted work, nor just because of the penurious state of the poetic purse in this country nowadays, for as noted earlier, Creative New Zealand have cut back on many projects [but for Rapatahana, interestingly not all, for some favoured projects still attract ample funding] so that, in the words of Norcliffe, 'Major literary awards have lost sponsorship and are struggling for support and even our most prestigious fellowship – the Katherine Mansfield Residency in Menton — has been so starved of funding that instead of a year the new recipient will only be offered three months. Major journals, which started as quarterlies have cut the number of issues a year: Landfall now two, Sport now one andTakahē now two.' And as David Eggleton wrote to me earlier this year, because of this precarious state of literary finance in New Zealand, he has to be 'hustling to survive.' Unfortunate, when one considers the millions being spent on unnecessary referendums for a new national flag, when we already had a good one — the Tino Rangatiratanga one! As here —

No, it's as much because of having to attempt to please everyone all of the time, because — despite what Norcliffe intimated earlier — there are diverse and divergent views as to what should be included and who should be included in such literary magazines. It's back to egoes and their echoes — particularly compressed within this tightness of the small populace of Godzone. Eggleton would make/already is a master politician, methinks. His editorial role presupposes and necessitates this.

Given all the above, David Eggleton, has also to be identified as a Polynesian poet, which straight away marks him out from his namesake David and from James Norcliffe. 'My personal background is that of a poet and writer of Palagi (European), Rotuman and Tongan heritage, with a special interest in contemporary Pasifika culture.' This is an increasingly vital aspect of the New Zealand poetry scene and I will return to it later in this series, for not only are there many gifted Pasifika lady poets, but also the work of John Pule, Doug Poole and — of course, the grandad of them all — Albert Wendt — to consider. Eggleton has much more to say here — all of which is valuable and viable. Suffice to say that he is an important and intelligent Pasifika poet (and Kiwi reviewer and writer and poetic patron) with a sizeable niche already in the basalt rock of the Aotearoa poetic. I have to point out here, that we were in the same classes at Aorere College, Mangere from 1966 on and that it was he who first acquainted me with Colin Wilson's The Outsider, not so long after. I was living in a caravan at the time when he delivered the Pan paperback to my unsteady door, telling me that 'I must read this.' 50 years have since swept past like a Mr Whippy van on methedrine.

There is some truth too in a tongue-in-cheek description of Eggleton by Justin Paton, who wrote back in 2001, 'Over there David Eggleton is riffling through his bumper-edition thesaurus.' He loves playing with words, torrents of words actually, and the ways they work and interpolate. Especially unusual ones. The same could also be said of the other two southern gentlemen poets here — and I have often wondered actually, if one necessarily rates quite highly on the ASD scale if one is to be an excellent poet. (ASD is of course, autistic spectrum disorder.) These guys also like to list, as for example, their published works...perhaps there is scope for a Creative New Zealand funded study of this in Wellington?

In the final stages of this commentary, I do once again have to say that despite the talent and craft and generosity of these Three Southern Gentlemen Poets, they are generally rooted deep in the English tongue in their own poems and do not give much space to other languages and the inherent cultural and genetic synapses thus intricately entailed, given that they have shown empathies in this direction. Again, for me, Tōku reo, tōku ohooho, tōku reo, tōko mapihi maurea — My language is my awakening; my language is the window to my soul. How much I would like to see both Takahē and Landfall and every other literary magazine publish in Māori, and of course other languages. I live in hope.

Well, well, well. We have traversed quite some territory here. I have not even mentioned other significant South Island poets — there's just so many, lah — nor publishers like Alan Loney's Hawk Press and the erratic but brave Catalyst poetry 'zine (both in Christchurch), although Jack Ross did of course discuss the latter and its audio magic in an earlier (2102) Jacket 2 commentary. But the terrain is just to mighty to traverse right now, while we must also remember that the three fine poets discussed here all started off with humble, small press publication. I suggest readers try and find Michael O'Leary's excellent 2007 book, drawn from his earlier thesis, entitled Alternative Small Press Publishing in New Zealand 1969–1999. And yes, expect to hear more about Michael too — he is somewhat left of Centre.

To finish for now, let's have another fine poem — this one from Jim Norcliffe. If I was to be somewhat of a stirrer it could also be seen as portraying the potential poetic gaps between New Zealand landscapes, and the concomitant critical stances and poetics so adhering to them, but I am sure that was not this poet's intention, eh. Yet with Jim, you never know...

Mycroft

Because I had no older brother

I was forced to be the oldest son.

I wasn’t much cut out for it.

I needed you to blaze the trail,

cut scarves on all the tall trees

I was forever getting lost in;

brainier, better, a dab hand with

an axe or a chain saw. Compass

in hand you would have strode forth

along roads I couldn’t even see

not having an older brother’s

clever sense of direction, acuity.

But I puddle along, Mycroft,

solving the odd crime here and

there, trusting I’ll grow into you

one day or, saving that, growing big

enough to fit into that Harris tweed

overcoat you left hanging in the closet

with theatre tickets, bus tickets, lolly

wrappers, but no compass in its pockets.

Silly really, as I never will. And now our

old man’s gone west, who’s left to care?

LINKS:

David Eggleton — the nzepc site is perhaps the best introduction to this versatile artist; includes several audio files too.

David Howard — similarly, the nzepc site is perhaps the most definitive introduction to this interesting poet. Then there is an essential interview with him from 2013 here — at his most scathing. (Deep South is another, somewhat erratic southern poetry site.)

James Norcliffe — he is the first to point out that his webpage needs a bit of caretaking, by the way. But what you need to find out about this unassuming poet, will be there.

Ngā whakaaro