Avant-Garde, I: Dada Conquers!

Visual forms of knowledge production and representation — examples of the practice Johanna Drucker calls graphesis — appear in the work of almost every important twentieth-century avant-garde movement. Many of the most compelling compositions of Italian Futurism, Dada, Surrealism, Fluxus, Situationist and Concrete poetics, and Pop and Conceptual Art throw maps and counter-maps into their multimedia mix.

In his “Zurich Chronicle,” penned in February 1916, Tristan Tzara reports magnificent goings on at the Cabaret Voltaire. Performances by Hugo Ball, Mme Hennings, and Tzara entertain the crowd, behind the audience paintings by Pablo Picasso and Hans Arp adorn the walls, along with F. T. Marinetti’s “geographic futurist map-poems.” Tzara likely has in mind the Italian Futurist’s “Examples of Words in Freedom” (e.g., “After the Marne”), which, although not maps per se, were nonetheless spatial compositions. In Marinetti’s “typographic revolution” and the painting of Picasso and Arp, page and canvas alike are multi-sensorial zones of dynamic force.

German Dadaists were among the earliest artists to make sustained use of maps as artistic material. Hannah Hoch, Raoul Hausmann, and Kurt Schwitters all experimented with cartographic inserts, and maps feature prominently in four of the best known early examples of photomontage: Hoch’s Cut with the Kitchen Knife (1920) and Hausmann’s Dada Siegt!/Dada Conquers! (1920), Tatlin lebt zu Hause/Tatlin at Home (1920), and ABCD (1923-24).

On April 12, 1918, the German Dadaists gave a rousing performance at the Berlin Sezession, at which Hausmann delivered a speech calling for “new materials in painting” to capture the ethos of the city. “In Dada,” he proclaimed, “you will recognize our real situation: miraculous constellations in real material, wire, glass, cardboard, fabric … your own utterly brittle fragility, your bagginess.” War-torn Berlin differed radically from neutral Zurich. After Germany’s military defeat in November 1918, a succession of crises — the Kaiser’s abdication, the West’s retributive postwar sanctions, soaring inflation, and the popular but largely ineffectual Sparticist revolution — led to the ascendency of a precarious Weimar Republic in 1920. Just as Zurich Dada wanted to rebuild language from the letter up, “Club Dada” allied itself with anti-State communists who aimed to remake the outlines of the map of Europe.

Photomontage was itself a cut-and-paste mix of Cubist collage, Zurich Dada performance, Futurist typography, and a Constructivist machine aesthetic. In a spirit Hausmann termed “perfectly kindhearted malice,” the Berlin cadre assembled this unholy hybrid into the best of political satire.

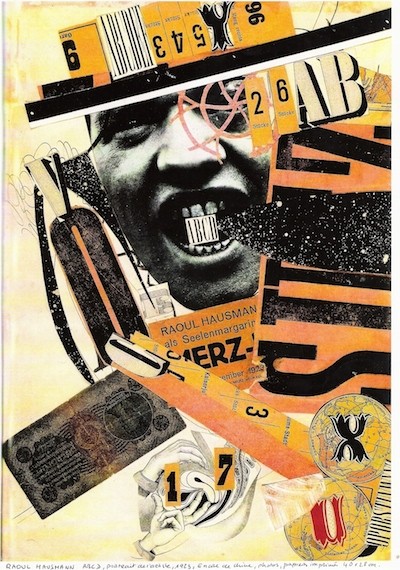

Innovations in mass publishing were essential to this work. With the explosion of photojournalism, maps — like the photographs, graphs, posters, and advertisements littering the works of “Club Dada” — became a standard feature of newspapers, illustrated magazines, and other affordable reading materials. Consider ABCD (1923-24) pictured above.

Much is rightly made of the text’s visualization of sound, as letters of the alphabet project loudly from between Hausmann’s teeth. The artist-poet called these “optophonetic” poster-poems, thus subtending the border between page and canvas, looking and reading, art and poetry, but language also weaves in and out of a photograph of outer space, a Czech banknote, an advertisement designed by El Lissitzky for a 1923 Merz evening in Hanover, and a map of Harrar, Ethiopia, which the poet Arthur Rimbaud once called home. That Hausmann employed maps in (self)-portraiture was no anomaly. As portraiture, ABCD captures not the singular essence of the individual but his travels, associations, and actions.

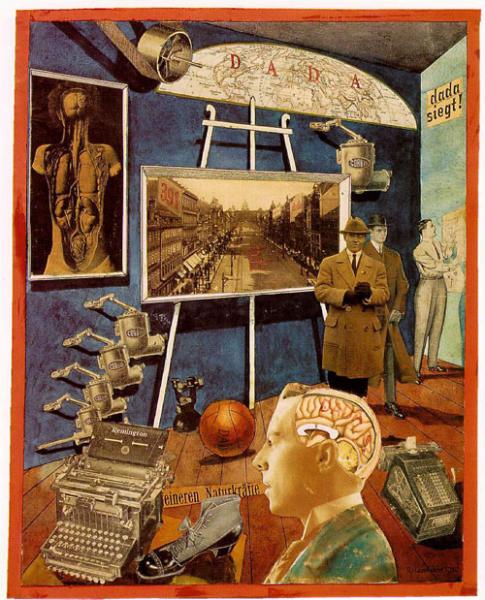

Hausmann’s photomontage also saluted the development of an international avant-garde. By 1923, Dada had established centers in Zurich, New York, Berlin, Cologne, Hanover, Paris, and elsewhere. More politically militant than their Zurich siblings, members of Berlin Dada decorated the First International Dada Fair (1920) by suspending an effigy of a German officer with the head of a pig and prominently displaying Hausmann’s Dada Conquers! (also known as A Bourgeois Precision Brain Incites a World Movement):

International Dada Fair, Berlin, 1920. Left to right: Raoul Hausmann, Hanna Höch, Dr. Otto Burchard, Johannes Baader, Wieland Herzfelde, Margarite Herzfelde, Otto Schmalhausen, George Grosz, John Heartfield. Dada Almanach by Richard Huelsenbeck, pg. 129.

Raoul Hausmann, Dada Siegt! 1920. Photomontage. 23.5 x 17 in.

Hausmann appears center-right beside an easel bearing the image of the Wenzelplatz in Prague (a stop on the 1920 Dada Tour organized by Hausmann, Richard Huelsenbeck, and Johannes Baader). The pictorial equivalent of the work’s subtitle, Hausmann appears as a dandyish and monocled bourgeois sophisticate poised to lecture the room. “D A D A” now paves the street anew, while the number 391 invokes the title of Francis Picabia’s influential magazine. Above the easel, a map of the Northern hemisphere similarly features the stamp of DADA; below center foreground, an exposed cranium reveals a man with DADA on the brain. Art, we are shown, permeates the mind, the city, the world.

Notable are the intertextual references to Huelsenbeck’s manifesto (also titled Dada Siegt), a snippet of which connects the mouth to the typewriter. Just above this text, a soccer ball playfully alludes to a four-page satirical broadsheet, Jedermann sein eigner Fussball (Everyone his own soccer ball), a pamphlet distributed in February 1920 by Wieland Herzfelde’s Leftist publishing house Malik Verlag and promptly censored the same day. Photomontage expresses a collectivist spirit subtending private property while reaffirming a common bond through an art practice emphasizing play, egalitarianism, and provocation.

Hausmann understood perfectly well the point Denis Wood would make decades later: cartography is not an innocent mimetic practice but a central player in the modern State’s military conquests, a marker of its dependence upon colonial enslavement and resource extraction, and a carrier of the ideologies of nationhood deployed to justify imperialist aims.

The “miraculous constellations” of photomontage mischievously redeploy the “real materials” of everyday life. At some of the most important scenes in twentieth century art history, the counter-map — like Byron the Bulb in Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow — loiters in the background plotting a revolution.

Works Cited:

Hausmann, Raoul. “Synthetic Cinema of Painting.” Ed. Lucy Lippard. Dadas on Art: Tzara, Arp, Duchamp and Others. New York: Dover Pub., 2007. 59–61.

Tzara, Tristan. “Zurich Chronicle, 1915–1919.” Ed. Hans Richter. Dada: Art and Anti-Art. London: Thames and Hudson, 1997. 223–24.

Counter map collection