'Invictus' and the negotiated revolution

Or Clint Eastwood's idea of the lyric poem

William Ernest Henley’s 1875 poem “Invictus,” from which the 2009 film about the 1995 Rugby World Cup and the dismantling of apartheid takes its title, reads:

Out of the night that covers me,

Black as the pit from pole to pole,

I thank whatever gods may be

For my unconquerable soul.

In the fell clutch of circumstance

I have not winced nor cried aloud.

Under the bludgeonings of chance

My head is bloody, but unbowed.

Beyond this place of wrath and tears

Looms but the Horror of the shade,

And yet the menace of the years

Finds and shall find me unafraid.

It matters not how strait the gate,

How charged with punishments the scroll,

I am the master of my fate:

I am the captain of my soul.

Even the trailer for this film that takes its name from this rather unknown nineteenth-century poem uses the recitation of several of its lines.

In the sombre, meditative recitation of Morgan Freeman — an African-American whose last name itself is an historical statement — the actor “channels” the unmistakable presence of the voice that we will later understand belongs to Nelson Mandela. The film is an intriguing confluence of presences: Clint Eastwood is its director; Matt Damon effectively captures the appropriate South African accent and plays François Pienaar, the captain of the Springboks, the rugby team that at that point were being Africanised into amaBokoboko; and Freeman portrays Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela, who in the film is charismatic and plays Madiba as a personally and emotionally isolated individual in his role as the recently installed president of the new, emancipated South Africa.

The story in the film is a simple and — to use a film-reviewer’s expression — “emotionally convincing” account of how President Mandela, the leader of a fragmented nation, “invests” belief in the captain of the nation’s rugby team in the lead-up to the 1995 Rugby World Cup when it was held in South Africa, the first event of its kind post-apartheid, in such a way that Pienaar and the team might be transformed into an unifying symbol that could help heal the damaged, haunted nation. Under apartheid and, partly, due to the effect of sporting boycotts, that team then known as the Springboks had previously symbolized the confrontational confidence and delusion of the normality of the Afrikaner nationalist government.

Depending on how cynical or how demanding we might be, the film can be seen in two ways: as an insightful illustration of an elder enacting his wisdom, a portrait of a man who lost much of his life through imprisonment and yet was still able to articulate and negotiate the necessities that allowed South Africa to survive both the impending disintegration of apartheid and the voiding of the African Nationalist Congress’s socialist discourse after the fall of the Communist Bloc; or it can be viewed as a typically Hollywood rewriting of historical events to suit the techniques of scriptwriters and the central concept of that folk-god, the Movie Hero.

But the film is not interesting for us here except for the fact that in it a poem — even if it is “Invictus,” a poem few readers without a specific interest in Victorian England would have heard of — is crucial to a key moment in the film where Mandela, ever the charming statesman, has to communicate an intention, an aspiration, to the poem’s recipient, the captain of a team who are all unlikely to have ever previously been open to the Poetic, such that Pienaar must not only understand it but must also, in certain ways, come to embody it.

Mandela gives François Pienaar “a mission,” and he takes it on as part of the duty implied in his role as the captain of the nation’s most important team: he is a Leading Citizen. Is that not what poetry has often done in modern nations, the Poet becoming spokesperson for the nation by embodying its articulacy, the lyric poem being the simplest expression of political aspiration and hope?

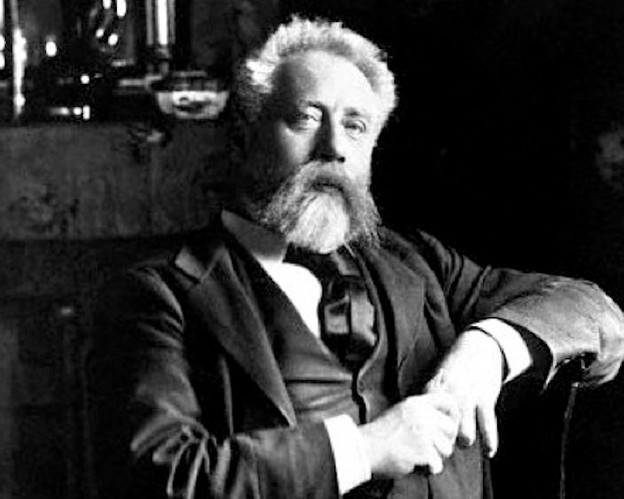

“Invictus” was written by William Ernest Henley (1849–1903) in 1875, during the Victorian era, a time that in the study of English literature has now largely been eclipsed by twentieth-century modernism. It was first collected in his Book of Verses, where it is the fourth part of the uninspiringly titled sequence “Life and Death (Echoes).” In his day the poem had a certain amount of success, conveying as it did aspects of Henley’s autobiography: he suffered from tuberculosis as a child and at the age of seventeen had a leg amputated.

His poem effectively embodies the Victorian ideal of a kind of emotional stoicism which for us in the twenty-first century might seem fraught with self-deceptions and the internalization of the Imperial. Yet for lay readers, as is testified to by the comments that accompany the poem in its various versions on YouTube, the poem continues its work of what might be called illustration and motivation. (Most moving to me was a comment written by a young adult who said that for her the poem was very important: she too was an amputee and knew the willpower required to live with that.)

Certainly, seen in the context of the twenty-first century, the poem hardly seems to deserve attention for its literariness. The sentiment it expresses, of determination and will, its emphasis on what has been heavily critiqued as the “unified subject” — or the idea of an independent Self — and its conventional language would not make it a likely object of study today, much less an admired poetic artefact.

Yet Mandela, it seems, mightn’t concur.

To the Mandela of the film that poem represents self-mastery and empowerment, those qualities that were at least one part of what made him one of the greatest leaders of the twentieth century, very Victorian qualities. As it’s presented by Clint Eastwood as director — I wasn’t able to verify it from the various biographies nor from Playing the Enemy: Nelson Mandela and the Game that Changed a Nation, the account by John Carlin that formed the basis of the astonishing story — Nelson Mandela read that poem while in prison and would bring it to mind in moments when he felt close to despair at what confronted him.

To ask the obvious: What confronted him?

For filmic reasons, Eastwood allows a good degree of ambiguity. There is no sense of other languages — whether Xhosa, Mandela’s mother-tongue, or Afrikaans, the “Language of the Oppressor” as it was called in those times of conflict, to mention only two of the nation’s twelve official tongues — being involved in forming Mandela’s sensibility, no presence of Communist or socialistic influence and their political circumstances, no indication that the liberation struggle in South Africa was connected to the anticolonial and civil wars in Mozambique, Angola, or Zimbabwe or elsewhere. Nor is it explicitly presented — most likely due to Eastwood’s interest in the trope of the lone man facing historical change, that he contemplates in Gran Torino, too — that for Mandela to have reached the point where he could become president of South Africa he must have been both well-capable of negotiating with those figures who were his antagonists as well as being able to allow the necessary ambiguities of expression that could allow those factors that contradicted his politicking to remain present, if unstated.

Mandela might not have made a good literary critic, but he definitely could have been an emotive civic poet.

After all, it is when Pienaar is unsure of how to motivate — note that term of both theatrical and managerial “acting” — his team, when members of the team are showing signs of resistance to his leadership, when the project of using a win in this most symbolic sport in the South African context to make gains in that other game, the politics of nation-building, seems doubtful or dubious, that Mandela passes on the commission of the poem. Later in the film, Pienaar is shown visiting Robben Island, seeing the quarry where the imprisoned members of the ANC were tasked with stone-breaking, and he himself is seen by the audience standing in the cell which held Mandela for many of those twenty-seven years of his sentence, as the entire poem “Invictus” is read in Madiba’s — via Morgan Freeman’s — deeply affecting voice. Visually, it is almost a dream-sequence, with a half-tone Mandela haunting those places the rugby captain wanders through. It has all the characteristic, manipulative charm of a powerful cinematic reverie.

That point at which the poem is recited, embodied within the ghostliness of the cinematic narrative, is that moment when Mandela’s past, the history of the struggle and Mandela’s own place in it as figure and person, are conflated with the ambition of the nation’s future, its chance for success, and it is then that responsibility is given over to Pienaar, the Hero who it is hoped could enable the microcosm of the rugby field to become the macrocosm of the entire country; the mission depends on his acting on the motivation or, to use the poetic term, inspiration, given to him by Madiba.

(Of course, I should have remarked earlier that “Invictus” is Latin for “unconquerable.”)

In this film and its version of South African history, the lyric poem does everything that it has always been expected to: it expresses individual integrity, defines personal feeling and enables an articulation that is a product of introspection, an articulation that can lead to action. In the poem the long-imprisoned freedom fighter who managed to win and become president and the conservative, until then apolitical, captain of a previously demonized sports team, who is able to reorientate himself in the political project of a new nationalism, are united by the lyrical “I,” which itself is a political figure.

In the transition between the “I” who is William Ernest Henley, the invalid author of the poem, and the reader embodied in Freeman as Mandela, or in Damon as Pienaar who is acting on Mandela’s self-transcendent nationalist ambitions, there is the primal, twinned poetic question of Author vis-à-vis Meaning. For all three of these literary figures — the commissioning father Mandela, the good son, Pienaar, and the god himself, in the Author William Henley — the poem “Invictus” is an articulation of what — to borrow a phrase — might be called “a will to power.”

Elsewhere, in another era, that impulse might have been called hope.

Through Henley and Mandela, Mandela and Pienaar, then Freeman and Damon, the “I,” “initial” person of the poem, is embodiment, the Persona, what is, in the very oldest of senses, an effect of inspiration.

The Clint Eastwood the director, a shadow of God, is himself a ghostly presence in all this and someone with a deep understanding of the metaphorics of the masculine, has taken the possibilities latent in the strange slippage that occurs in the Persona, as a means of creating a rhetorical, literary mode that might stand against the inevitable “facticity” of cinema’s moving-image and its instrumentalist emotionalism. Here the lyric poem becomes an object not transhistorical in being transcendent, but transhistorical instead in that it is an artefact, much as the Self that can move through discourses and histories and due to the nature of those systems be “rendered” historical, “factual,” by each.

The poem “Invictus” then is not merely, as the film’s trailer would suggest, a kind of motto for the ethos of the story and its explanation as to why South Africa, despite all its potential conflicts, didn’t degenerate into civil war during the demise of apartheid. It is actually made to be an example of archetypal poesis. But the Thing being made might not be the poem but rather the Person, the individual, the mysterious, polyvocal adoptable Self.

Maybe the unconquered of the poem is that person who is always spoken by the Poem in the voice of the Reader, who is motivated by making and remaking, who is that persona inevitably recited, uttered, amidst the cinematic blur of any History?

Postscript: We should remember that, in lieu of a final statement before he was executed, Timothy McVeigh, the Oklahoma City bomber, gave a hand-written copy of the poem “Invictus” to his jailer. In the US media afterwards there were suddenly a range of commentators drawn to literary criticism, to analysing and defending Henley’s inspirational lyric poem.

Drafts of this essay were presented at the 2012 Poetry and Revolution conference at the Contemporary Poetics Research Centre, Birkbeck College, University of London, and at the Institute for English Language and Literature, Freie Universität Berlin. The essay first appeared in a Portuguese translation by Înes Dias in the magazine Cão Celest, issue 2.