Clumsy, erroneous, freakish, foreign

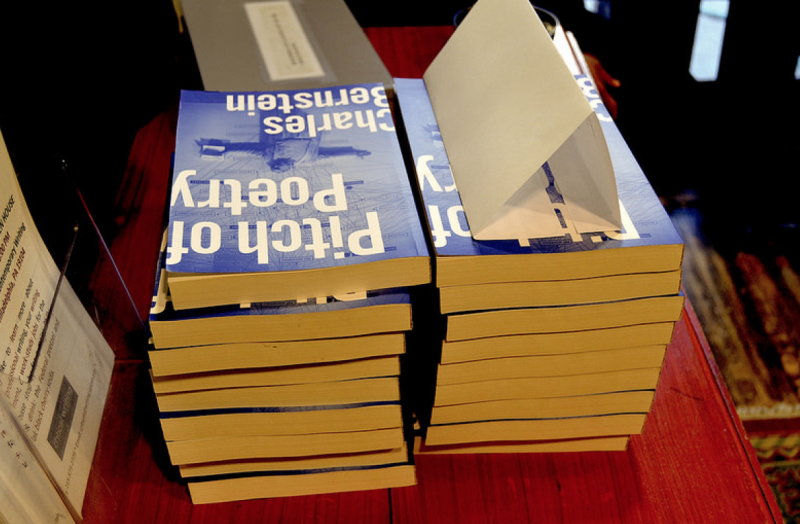

Charles Bernstein's new book of essays

What follows is the text of an introduction I gave at a book launch event marking the publication of Pitch of Poetry (University of Chicago Press, 2016) held at the Kelly Writers House in Philadelphia on April 12, 2016. — Al Filreis

This is a book full of important essays. And of course I urge you to read the whole thing. The seven essays under “L=A=N-G=U=A=G=E.” The seventeen pieces about individual writers under the titular heading “Pitch.” The comic deadly serious epilogue under “Bent Studies,” that catalogue of recalcitrances, aphoristic chips from the workbench of a life’s work of radical anti-sectarianism, index-sourcework for what I take to be Charles Bernstein’s most significant contribution: his incessant anti-anti-intellectualism. If you can’t manage all that reading, I recommend starting with the eleven collaboratively written essays under “Echopoetics,” for there is where readers will locate the heart of this poet-critic’s intellectual generosity and aesthetic flexibility. “Echopoetics” is a poetry of call and response. Its poetic theory and its frankly affirmed values are discernible variously in these essays, talks, conversations, statements and anti-programmatic programmatic dicta.

Echopoetics is pitched at you here, opaque yet direct, full of the impossibly restless curiosity that is characteristic of Bernstein as a temperament, calling modestly for the continuing modern dialogue of reason and imagination, for collaboration founded on pataquerical qualities, for “midrashic anti-nomianism”: made happily weak rather than strong by over-reading — clumsy, erroneous, freakish, foreign (in the sense historically denounced by anti-Semites), incongruous, anomalous, polyverse (borrowing from Lee Ann Brown), paracritical (borrowing especially from Jerome McGann), contradictory (borrowing from Marx and Whitman synthesized), artificial (borrowing from Oscar Wilde), degenerate (again turning around the fascist valence), bent, pidgin, nonstandard, anti-absorptive, thick, hyberbolic — feverishly pitched.

Echopoetics is pitched at you here, opaque yet direct, full of the impossibly restless curiosity that is characteristic of Bernstein as a temperament, calling modestly for the continuing modern dialogue of reason and imagination, for collaboration founded on pataquerical qualities, for “midrashic anti-nomianism”: made happily weak rather than strong by over-reading — clumsy, erroneous, freakish, foreign (in the sense historically denounced by anti-Semites), incongruous, anomalous, polyverse (borrowing from Lee Ann Brown), paracritical (borrowing especially from Jerome McGann), contradictory (borrowing from Marx and Whitman synthesized), artificial (borrowing from Oscar Wilde), degenerate (again turning around the fascist valence), bent, pidgin, nonstandard, anti-absorptive, thick, hyberbolic — feverishly pitched.

“So let’s pitch in,” he says, in yet another of his silly-seeming punny pitches. He ironizes, he leans, it's not in his constitution to proselytize, but he does, at moments, unironically seek a collaborative engagement.

Pitch is of course — perhaps first — the sound of poetry, something Bernstein has thought about (through his sound studies and the Electronic Poetry Center and PennSound) as deeply as anyone this last quarter century. Pitch is register.

But pitch is also the attack or approach, the angle — ideological, yes, and/yet primarily perspectival. This new book Pitch of Poetry makes his best pitch yet for the progressive efficacy of “dialogic critical encounters.” For, truly, you can’t evict an idea. A concept, applied in this book in one major essay and many other references to Occupy, that has its origins, for Bernstein, in European modernist anti-fascism in the 1930s.

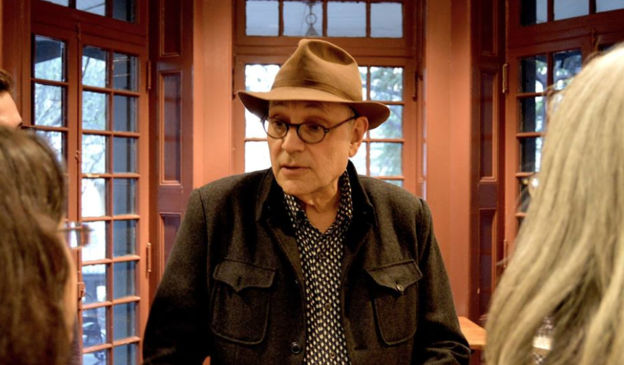

He likes saying: You have to love originality so much, you keep on copying it. Thus monotony — such as that produced by Charles Reznikoff’s monolithic Testimony — entails a work of writing that speaks not for itself but as itself. This is a difficult but key distinction. This book makes us realize that Bernstein’s goal, ultimately, after all these years, has to discover a pitched state or situation in which he can speak as himself. When he praises Raymond Federman’s “Take It or Leave It,” by commending how such work “shows [that] digression and the comic can weave their way around an empty center without betraying it,” he is I think striving to speak about himself — inside the ideal of the engaged writing life. At left: part of the overflow audience at the Kelly Writers House on April 12, 2016.

He likes saying: You have to love originality so much, you keep on copying it. Thus monotony — such as that produced by Charles Reznikoff’s monolithic Testimony — entails a work of writing that speaks not for itself but as itself. This is a difficult but key distinction. This book makes us realize that Bernstein’s goal, ultimately, after all these years, has to discover a pitched state or situation in which he can speak as himself. When he praises Raymond Federman’s “Take It or Leave It,” by commending how such work “shows [that] digression and the comic can weave their way around an empty center without betraying it,” he is I think striving to speak about himself — inside the ideal of the engaged writing life. At left: part of the overflow audience at the Kelly Writers House on April 12, 2016.

Thus, of course: poetry, in particular. It’s necessary, for it is the answer to the question, “Can the authorities come banging in, and evict an idea?” Poetry. The boldest political statement: “To write prose after Auschwitz is barbaric.”

In a section of the essay “This Picture Intentionally Left Blank” — the section is titled “Letter from Warsaw” and I found it terribly moving — he describes his and Susan Bee’s and Tracie Morris’s visit to Warsaw and to Lodz. It was a first trip to that haunted landscape. Susan’s mother was born in Jewish prewar Poland, moved to Berlin with her family when she was five, whereupon a diasporic journey began that rendered them multilinguistic survivors (and artists). Bernstein reports that he realized at that moment that he is “someone whose intellectual and cultural foundations are European,” and by that he now means to refer to dislocation, alienation, and a specifically historical form of radicalism. He found himself standing “on the ground,” as he puts it, “of a great experiment from the decade before I was born, which aimed to expel difference in order to increase harmony through sameness, but the move toward homogenization versus miscegenation is powerful in the Americas as well, since the poetics of the Americas is the continuation of European poetics by other means.” And so — after years of reading and hearing his poetry, criticism, interviews, reviews, collaborations, liberettis, and translations — we arrive at the pitched origin story of a poet’s pitch for difficulty and difference. “The power of American poetry,” he writes, “comes from the mixing of many languages and the resistance to the dominance of any one language, including English, or proper English, anyway. It is the overturning of standard English by second languages and vernacular/dialect speakers that defines American poetry.”

The Pitch of Poetry essayistically embraces such values, but in its epilogue lists them under the hilarious yet not entirely ironic heading “Positive Literary Terms of Art.” Such terms:

estrangement

stuttering

deformative

stray marks

dysprosodic

dis-stressed

aversive

nonstandard

etc.

Although Charles Bernstein been called to this podium [in the Arts Café of the Kelly Writers House in Philadelphia] many times over the years, it surely has not been often enough to read from his own work. So let us welcome our dear distressed, aversive, non-standard friend Charles Bernstein.