Upheaval and return

Julia Bloch

J2 editor Julia Bloch reviews three poetry titles on earthly and bodily reorganization.

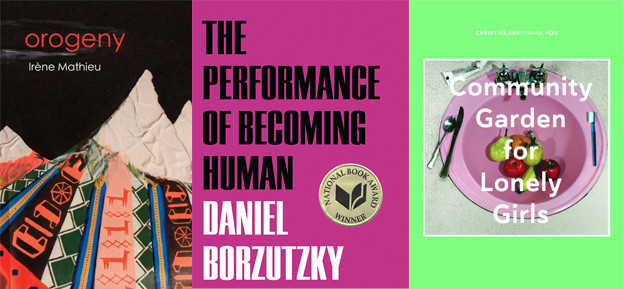

Orogeny, Irène Mathieu (Trembling Pillow Press, 2017)

Irène Mathieu’s debut book of poems, selected by Megan Kaminski for the Bob Kaufman Book Prize, takes its title from the geological term to describe a “mountain-building event”: moments at which the earth’s crust folds, leaving whole new landscapes and ecologies in the wake of upheaval. Mathieu’s poems often depict the way human events change our perception of the physical world, in richly textured images that often turn on the brutally unexpected, as in “ghazal for twins”: “one brother unfolded from the other / where his father’s hand was missing. // one mother was opened and drained / until her blood ran clear with fish.” Or “g as in god,” dedicated to Ahmed Al-Jumaili, an Iraqi immigrant murdered in 2015 outside his Dallas, Texas, apartment building, a poem in which “we want god / to appear as an ambulance.” For all these poems’ conceptual range of motion, there are also moments of return, such as in “thermodynamics,” a poem about hair straightening in which it is discovered that not all processes are final: the child who appears in school photos ringed by “oak boughs” and “holy magnolia” learns late in life that “nothing wild can be turned rigid for long.”

The Performance of Becoming Human, Daniel Borzutzky (Brooklyn Arts Press, 2016)

Daniel Borzutzky’s National Book Award–winning volume uses the line to thematize border-based cruelties and losses, beginning with the problematized subjectivity of its opening poem: “I live in a body that does not have enough light in it / For years, I did not know that I needed to have more light / Once, I walked around my city on a dying morning and a decomposing body approached me and asked me why I had no light.” Nearly all the (long, often paragraph-length) lines throughout this book have no ending punctuation, so that the edge of the page stretches and snaps into tension with Borzutzky’s hurtling images. Consider a poem like “The Broken Testimony,” in which the constantly shifting points on a map call into question our fragile social relations: “Take us to Kindred Hospital on Montrose Avenue, you say, to the beat of the hovering scavengers a few blocks east of California Avenue // A scavenger has a shovel and I write him into our faces / My face {to the beat} relational to your face {to the beat} relational to the tar that holds us together relational to the tar that binds you to the earth.” Even given the declarative force and often unrelenting violence in this book, Borzutzky’s poems open as much as they shout, as in this twist on Creeley’s anthem to the US American frontier, followed by a shock, followed by an invitation to the reader: “What do you make of this darkness that surrounds us? // They chopped up two dozen bodies last night and today I have to pick up my dry cleaning. […] What does it say? What does it say? What do you want it to say?”

Community Garden for Lonely Girls, Christine Shan Shan Hou (Gramma Poetry, 2017)

Christine Shan Shan Hou’s book traces the affective lines of a body navigating mythology, genealogy, and the unexpected layers of meaning embedded in the quotidian, leading to poems of wry and sometimes wrenching juxtaposition. For example, “I’m Sunlight” is whiplash-like: “Living with hard water has been hard on my hair. / I keep my mother tongue in my mouth to look less creepy. // I peruse biographies of queer, literary figures from the early / 20th century in hopes of stimulating my situation. Ding! / The kitchen timer goes off. I open the oven door and to my / surprise it starts an earthquake in China.” “Bubble” surrealistically considers the objects invited by absence: “What is this mission / that I’m after? / Is it finding the hole / inside of me and falling / through it / triumphantly / naked / while reasoning / with fingers / and star / voices / that drain me / until my death?” When we think of a garden we often think of its plot, geometrically speaking, and this book, too, is laid out on a sequence of grids whose joints and measures shift and jolt: Gramma’s luminous book design, featuring Sandy Skoglund’s Pink Sink on the cover and an inventive layout, helps to emphasize the poems’ investment in a continual search not just for the right shape but also for the right story.