Citizenship in contest

Orchid Tierney

Orchid Tierney rounds out the year with three reviews of 2019 poetry titles.

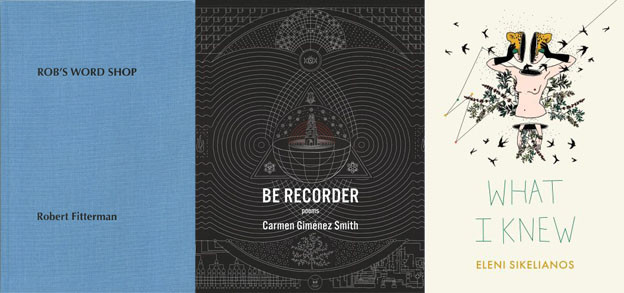

Robert Fitterman, Rob’s Word Shop, archive and afterword by Lawrence Giffin (Ugly Duckling Press, 2019)

Language is for sale in Rob’s Word Shop. Words and letters are bartered or exchanged for cash or goods, and receipts pass hands, in a public chain of supply and demand. Meanwhile we eavesdrop on the vendor and his customers as they negotiate between inquiry and material desire. Many snippets of dialogue are innocuous but convey a hint of the hyperreal. Lines like “it’s cheaper if you buy the letter” and “Rob, has anyone brought back their word?” punctuate the vendor’s thoughtful murmurs and hesitations: nonwords, inaudible utterances, or quasi-words are plentiful and priceless as they capture the convivial atmosphere of the temporary store. Rob’s Word Shop, as Lawrence Giffin declares in the afterword, “was a process like any other.” As we learn, customers were “mostly friends or friends of friends,” which raises the following question: how much does this book enclose a particular literary community’s critiques of consumer culture and conceptual poetry that are already circulating in their academic-adjacent exchanges? Giffin’s disclosure of the clientele’s demographics inspires another line of inquiry: how would Rob’s Word Shop fare in less familiar territories? Regardless of the answers, it is clear that this bookundertakes a serious meditation on the politics of the document, one that endeavors to divest the power of the word from being the beginning and the end of a literary process.

Carmen Giménez Smith, Be Recorder: Poems (Graywolf Press, 2019)

In Be Recorder, Carmen Giménez Smith perforates the grotesque mask of a contested nation. Rejecting a monolithic formation of the lyrical subject, the poet tests the edges of what it means to be simultaneously an inside and outside observer of “America.” This observer is an inhabitant of plural identities: “I’m post-post-post,” the poet writes, “I’m double crossing.” Be Recorder is profoundly activist in its discerning absorption of and resistance to American’s monstrous imprinting of fantasies onto the body. With lines like “This land made us / old phantoms,” “They built the US bunker in heaven / for the citizens who filled shelves / with formula guns toilet paper plates” and “I believe in the state / in the end while the apocalypse roars outside,” the poet propels the reader toward multiple refusals of the state’s branding. Yet, there are also determined declarations of freedom. “I only ask / that we get started,” writes the poet. “This is our first step toward world domination.”

Eleni Sikelianos, What I Knew (Nightboat Books, 2019)

What I Knew is a long poem of the glocal. Entangling the personal with worlding language, this book explores the dreamy, private, and mysterious shelters of poetry from public bombardments, search engine algorithms, violent news headlines, and mass media. “Will you let this Web know more about you,” writes Sikelianos, “than you yourself know?” This isn’t a book, however, about the staged overlapping of familial and public worlds. Of course, social anxieties are leaky: “The daughter is doing drills ‘if there’s someone with a gun,’ and crouches,” writes Sikelianos, “This is how she learns in school.” Rather, in What I Knew, the poem is a protected space, and not a sacrificial one, for meditation, dreaming, and nondisclosure. This quietude against the sheer bombardment of gender violence and global conflict is a rejection of poetry’s slippages into commodification. And despite the corruption of the world, there is too a quiet optimism for poetry’s protected data: “The last line of the uncorruptible poem is more beautiful & actually spells / Victory / Victory.”