Strange definitions

Kenna O'Rourke

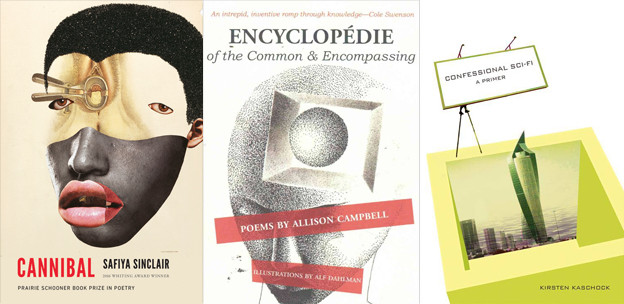

Three capsule reviews of weird vocabularies: Cannibal by Safiya Sinclair, Encyclopédie of the Common & Encompassing by Allison Campbell, and Confessional Sci-fi: A Primer by Kirsten Kaschock.

Cannibal, Safiya Sinclair (University of Nebraska Press, 2016)

Safiya Sinclair prefaces her debut full-length text with the etymology of the word “cannibal”: “from the word caribal, a reference to the native Carib people in the West Indies, who Columbus thought ate human flesh … [b]y virtue of being Caribbean, all ‘West Indian’ people are already, in a purely linguistic sense, born savage.” This is the history which pervades this collection — a lineage of exoticization, a vocabulary of erasure. Sinclair writes biting, beautiful verse on the resistance inherent in her very existence; she asserts the meaning behind saltwater, pearls, plums, blood. The speaker articulates a “known-wound / [they are] salting as proof of existence,” all the while letting colonizers know: “nothing here will grow politely.”

Encyclopédie of the Common & Encompassing, Allison Campbell, ill. Alf Dahlman (Kore Press, 2016)

This small surreal encyclopedia brings a new sense of heft to the poetic act of list-making; the poems in this book are, as Campbell puts it, “ripe for ripeness.” Deeply personal and unreservedly absurd, Encyclopédie shifts abruptly between existential meditation and wild portraiture — a skeleton yearns for forbidden love, a speaker looks over their collection of taxidermied exes. In the gaps, we find familiarity: “The plants die because they’re only watered with leftover half-glasses of what we don’t drink. Either we are thirsty or the plants are.”

Confessional Sci-fi: A Primer, Kirsten Kaschock (Subito Press, 2017)

“Ghosts either do not exist, or they are dumb here. They drop into milk and are swallowed,” Kirsten Kaschock writes in this book of past, present, near-present, near-future, far-future. The characters that inhabit Confessional Sci-fi, if not ghosts exactly, are just as dark and strange and filled with past-life longing as proper specters. The Divine Lorraine hotel promises to serve as a spaceship when the time comes; a daughter trades her mother’s vintage fetish porn for tools to skin cats; a fish whispers “fool” to a runaway child; an angel with a chimp’s face guides visitors through rooms of frogs and clones. Full of odd feeling, and more often than not grotesque, the book reckons with the inexplicable in twisted, funny lines: “I made a dance about torture. I choreographed it. // Yep.”