Transfigurations/abstractions

Kelly Liu

Editorial assistant Kelly Liu breaks down the poetics of the three translated booklets of Ideas Have No Smell.

Ideas Have No Smell: Three Belgian Surrealist Booklets, ed. and trans. M. Kasper (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2018)

Transfigured Publicity, Paul Nougé

Transfigured Publicity is exactly as the title advertises: publicity transfigured, propaganda reconceptualized, messages reinterpreted and reread, as each page materializes into a literal wall on which humorous public messages are plastered. Veering between the aphoristic and the cliché, the sincere and the ironic, the authoritative and the subversive, one such message proclaims, “DON’T FORGET / IN / THIS / CITY / ONE CAN / WITH NO FUSS / PROCURE / AUTOMATIC PISTOLS / AND / SPEAKING MACHINES,” a statement at once infused with Futuristic didacticism and grimly critical of technology. Nogué skillfully maneuvers the size of individual words and the direction of his writing to suggest alternative readings counterintuitive to common sense, to question public advertisements whose logic goes too often untested. He reminds us, in the end, that “their manipulation is not without a certain danger.”

Abstractive Treatise on Obeuse, Paul Colinet

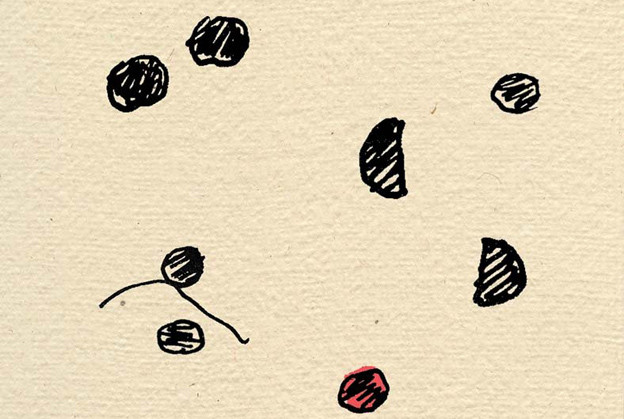

Colinet’s Abstractive Treatise on Obeuse centers around a playful, imaginative construction of the character “Obeuse,” visually represented by a shaded circle. Obeuse might be a deliberate misspelling of the French word “Gobeuse,” a (feminine) identity who swallows things whole. Colinet’s Obeuse, however, is presented as a masculine identity. He is rebellious, anticonformist, and facetiously militant; he joins other obeuses in reformatories, shatters lutes supposedly belonging to Marshal Foch, and squashes universities. Each page of the collection contains a cryptic scene involving Obeuse explained by a few witty words and evocations, reminiscent of the at once simplistic and penetrative rhetoric of a children’s book. Obeuse, pictorially transformed with and against his surroundings, semantically enjoined with brief texts meant to narrate the drawings, is at once abstract and abstractive, existing both as an autonomous geometric identity and as a diagram abstracted from larger realities until, by the end of the book, “MiLLiONS OF OBEUSES THEMSELVES DiSAPPEARED,” and the single shaded circle that we begin with turns at last into a line — connective, relational, never apart from others and the world.

For Balthazar, Louis Scutenaire

Scutenaire, affectionately called “Scut” by friends and companions, collages a diverse range of writings in For Balthazar. It comprises of pithy surrealist imagery such as “Big statue of happy, big flag of sad” and short poetic descriptions such as “Between us there was a flower.” It also includes longer philosophical wanderings, one of which praises academic painters who prefigure modernist artists, revolting against an absolute disavowal of tradition in light of the new. Another catalogues and celebrates literary and scientific figures throughout the centuries, while still others relate parables that read like anecdotes and leave us wanting more. Four scattered pages in the booklet each contain a single alphabet, which together forms the name “Scut.” Deeply personal, brazenly honest, unexpectedly revelatory, and at times comically crude, Scutenaire manages to arrange fragmented references into a charming whole that, perhaps, culminate into an equally hybrid self.