Open online course on modern poetry enables Pakistani student find his university and his writers' house

An article in the Christian Science Monitor features three talented students who found their college experience in unusual ways. One of those three is Taha Tariq — of Lahore, Pakistan — who discovered Penn and the Kelly Writers House through “ModPo,” the free and open online course on modern and contemporary American poetry offered through the House. Here is a portion of the article. The whole article can be found here.

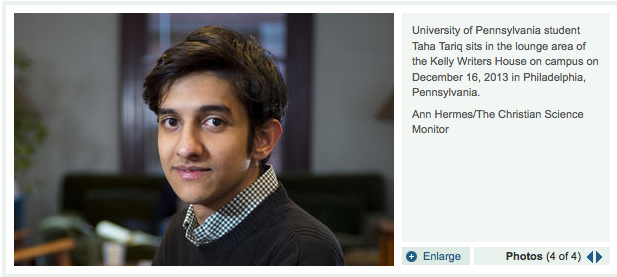

When I meet Taha at the White Dog Cafe in the heart of the University of Pennsylvania campus in Philadelphia, it is apparent that he loves language – and conversation. He is a geyser of ideas, large and small, and offers snippets of insight and self-awareness.

Over smoked salmon artfully arranged on a rectangular plate, he proclaims his passion for author Jodi Picoult ("The judgments, decisions, moral dilemmas, and questions she presents leave me speechless," he says). Later, we visit Hill College House, his dorm, and meet his suitemates on the fourth floor. I learn that he has seen plays around the city, been a guest at a roommate's home on Long Island, and led late-night debates in the communal study space.

Taha is also intrigued by an ongoing conversation he has been having with a street vendor about religion. We sit on a stone bench amid fallen leaves as he describes the moral twists the man's narrative suggests and his plans to write about it, not for any class, but for himself.

Taha is interested in problems of perception and understanding. In Pakistan, he says, a relative and a friend's uncle were both injured by bomb blasts near mosques. "I feel I should be doing something about that," he says, during a Friday evening phone conversation. It's unclear what Taha will make of his future, but he is ambitious, imaginative, and eager to have an impact. It is odd, he says, to realize that just a year ago he had stumbled upon a MOOC and was watching Dr. Filreis online – the same professor he now calls "Al." Filreis is his adviser and teaches the seminar he recently took on representations of the Holocaust in film and literature.

Taha is interested in problems of perception and understanding. In Pakistan, he says, a relative and a friend's uncle were both injured by bomb blasts near mosques. "I feel I should be doing something about that," he says, during a Friday evening phone conversation. It's unclear what Taha will make of his future, but he is ambitious, imaginative, and eager to have an impact. It is odd, he says, to realize that just a year ago he had stumbled upon a MOOC and was watching Dr. Filreis online – the same professor he now calls "Al." Filreis is his adviser and teaches the seminar he recently took on representations of the Holocaust in film and literature.

Taha came across Filreis's enormously popular MOOC on modern poetry, known among its community simply as "ModPo," by chance. Google delivered him to the website of Coursera, an education firm that produces online courses, and he browsed, then signed up for the class. Taha says he was drawn in by the lectures – conversations that introduced him to new poets and new ideas.

He was also attracted by the bohemian culture of the Kelly Writers House – a literary salon on the Penn campus that hosts poetry readings, film screenings, lectures, and cultural events. It was founded by a group of students and faculty in 1995 in a spirit of cultural communitarianism. As a high school senior in his native Pakistan at Lahore Grammar School, a network of private schools that prepares students for British-style exams, Taha was struck by what he saw as a relaxed relationship between professors and students in the MOOC and at Kelly Writers House events.

"The videos weren't just lectures or presentations," he says, but "students sitting around with a mug of coffee, discussing the poems. Some of them fumbled, some of them struggled, some of them got interpretations completely wrong, so I didn't feel like someone was imposing their interpretation on me."

Interpretation – not just of poems but of ideas – matters to Taha. As a high school student, he and friends started an intellectual magazine called Pineapple – named for one fruit Pakistan struggles to grow – that aimed to provoke. The first issues include articles on "Shia Genocide"; views of Pakistan from youth in India, Afghanistan, Egypt, and the US; and a contrary look at the Taliban.

"We felt there were a lot of issues people in Pakistan didn't talk about," he says. "We felt the problem of extremism and radicalism was because people wouldn't see things from a different perspective."

When I speak with Filreis, a charismatic bearded professor, he complains that people criticize MOOCs without differentiating between those that are done well and those that are not. He is sitting at a computer and clicks between discussion boards, Facebook posts, and live "office hour" chats led by teaching assistants who discuss poems in the video lectures (the TAs have become ModPo celebrities, too).

Filreis reads comments aloud to demonstrate that users employ different tones in different settings that reflect very human interactions. A user mentions an upcoming chemotherapy session on Facebook. Classmates send supportive wishes. On the discussion board, students eloquently debate the meaning of a poetic image.

"This sounds like real people to me," says Filreis, who notes that there can be bad big campus lectures (he uses more colorful language) and terrific big campus lectures, subpar online classes and terrific ones with intensely engaged students. "I am trying to make a model of how a MOOC can be personal," he says. Filreis is also doing the MOOC, which is filmed at the Kelly Writers House on campus, "because the outreach is fabulous. Poets I care about are being read by thousands and thousands of people."

About 80,000 people have taken ModPo since it launched in fall of 2012, and last year, says Filreis, about 150 students with no other connection to the university made unsolicited donations totaling about $7,000 to the Kelly Writers House.

The MOOC has also become a tool for attracting students such as Taha to Penn, says Jamie-Lee Josselyn, who since 2012 has been in charge of recruiting talented writers. This year, 400 potential students have contacted the school, double the number from last year, which was when Taha reached out to Ms. Josselyn. She says Taha's insights on ModPo discussion boards and his entrepreneurial approach with Pineapple magazine "is honestly something we are really looking for."