Herman Beavers, the tundra of yes

A review of 'Obsidian Blues'

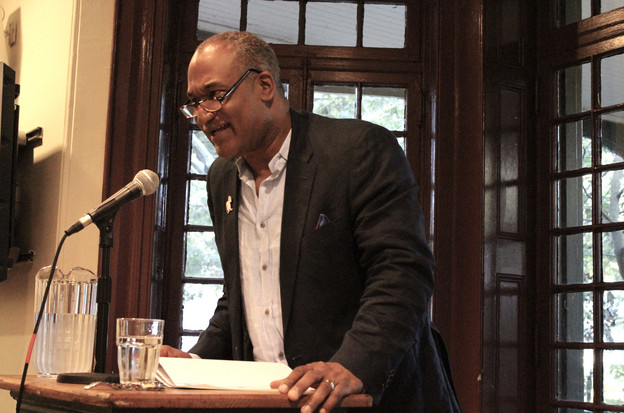

On September 9, 2017, at the Kelly Writers House, Herman Beavers read poems from his new book, Obsidian Blues. HERE is a link to the video recording of the event, and HERE is a link to the audio-only recording. For more about the event, and for a profile of Herman Beavers, click HERE to view the Writers House web calendar entry. I had the honor of introducing the reading. Below is my introduction, slightly modified for Jacket2.

* *

Obsidian Blues, to quote Herman Beavers quoting Ralph Angel, is itself “a still life and a way to get home again.” The poems in this powerful collection often present still lives of stilled lives. The speaker can see “Apples. / The way the light / betrays them” in a poem,“Obsidian Blues 43,” about a guitarist whose stringy wail (“strings judding like a systolic ghost swaggering”) sings a song of variation that repeatedly requires renaming. One such tentative title is “Still Life with Guitar and Heartstrike”; another is “Landscape with Skull and Banjo.” This is a poem of many titles, yet it, as a whole, is a wholly inclusive poem. Here and elsewhere in the volume, a poem is presented as a form of interarts blues — at one turn it is a canvas, at another a bright blue space washed with graphite (I think, as I read: that must be the writing itself). Then the poem is a work of “taut clarity” — a sundering, a moving choke-sob, a “tundra of yes.”

(A personal aside. I know this poet personally — have, happily, for decades. Encountering one of his speaker’s phrases, “a tundra of yes,” I mark in the margin: “I know this particular Herman Beavers.” The affirmative is never out in the clear, in the life, and now, I realize, in the poems — does not stand in the clarified, non-liminal terrain of easy “yes.” The poet has always generously said yes. The poems, at least here, are wary and selective.)

Here’s the still life of another poem: we see a close-up of the toxic, lacerated walls of post-Katrina New Orleans. On one wall receding water has elaborated a frantic sweetness. And another poem: A father refuses to let his daughter look at an eclipse of the sun. It is a powerful, though fleeting, scene of instruction: precise, efficient, yet (I find) hugely sad. A stern familial still life of large emotion caught behind a thin screen of visual memory.

Here’s the still life of another poem: we see a close-up of the toxic, lacerated walls of post-Katrina New Orleans. On one wall receding water has elaborated a frantic sweetness. And another poem: A father refuses to let his daughter look at an eclipse of the sun. It is a powerful, though fleeting, scene of instruction: precise, efficient, yet (I find) hugely sad. A stern familial still life of large emotion caught behind a thin screen of visual memory.

Herman Beavers’s roots are after modernism per se, yet he is a poet deeply invested in fragmentation. H.D. or Jean Toomer sees what Katrina wrought of the old tropes. The cubist rose of the poem called “Omphalos” leads to the question of the aesthetic revolutionary: “What might we make of a deep thing like rose petals?” The speaker there asks this Steinian question of an enormous present ache, the body in pain as a “lamp to the galaxy.” I think of Williams’s “The rose is obsolete” and of his America gone awry into pieces. The premodern rose is outmoded and insufficient, yes, but do we not keep returning to it again and again, making it and its galaxy of worries anew?

“In a Tangle of Scars: A Suite in Five Movements” gives us six of Beavers’s voice poems, familiar to those of us who have followed the shaping of his poetry out of the Cleveland sound. The “Suite” consists of a preface and five of these movements. These indeed are the local, remembered voices Beavers has been voicing for many years as the poems have emerged from within — and alongside —his original critical readings of Morrison, McPherson, Gaines, Sterling Brown, and his mentor, the late Michael S. Harper. I don’t know for certain that Toomer’s Cane is also in the mix, but I would guess so. The World War I vet who, back home, buries his medal to keep from getting lynched, whose verse-monologue, “Dangerous,” ends with what might well be the ars poetica of these many years of poetic work: “I can’t even begin to help you understand.” It’s a phrase uttered humorously ("I can't even...") in context, but there is not a more earnest sentiment to be found in these pages. In the suite we also encounter the guitarist who met Bird in Jersey in ‘57, lent him money and then was told the truth (as if it was an arranged transaction): that Roy Rogers and Trigger played better guitar. The truth won’t set you free; it’ll just make you mad. Another ars poetica, although political this time.

A further suite voicing: the song of the nine-year-old boy, later a shameful prisoner, lifted up from hiding in the bushes by “the black lady librarian” who might (in a better educational universe) have been able to set him straight. Might have accomplished that teacherly feat, but did not. Yet another voice — alas not that of the doomed speaker but, let us suppose, Herman Beavers’s — reckons sadly that the act of hiding from learning, evading the library of books presided over by this person who might have saved him, the boy’s “feet were planted in the only soil that could sustain you.” It is the nuted, typical tragedy readers are inevitably aware, in these poems, that the poet himself learned early to avoid.

The son of the 25-year old daddy, the daddy ceremonially oiling his old catcher’s mitt. The father is a veteran of World War II, the deadly Sicily campaign, and of a segregated army. The child of this man, pondering devotion to quotidian ritual, is led to the much-later moving question: “Will I ever give anything, anyone, this kind of love?” I cannot imagine a reader of this book who does not sense an authorial response to that question: yes, though it’s difficult and that difficulty is precisely in the poems we are reading. Again the “yes,” in a tundra of yeses, is to be found complexly in these poems. For in this writer’s work we are asked to work similarly, to make something of a deep old image like rose petals — make songs of our present enormous ache, a darker yet also lighter blues; to voice the stories of the vet who had to burn his uniform and bury his bravery; to use someone else’s poems to reassert memory (despite the speaker’s collapsing into tears when staring at an old photo of a lover taken by cancer) of dear ones who, though gone, are sustained in stilled lives of words and thus point the way back home.