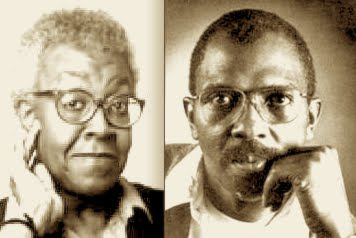

Etheridge Knight's 'The Sun Came' and Gwendolyn Brooks' 'Truth'

LISTEN TO THE SHOW

On PennSound’s Etheridge Knight page we offer single downloadable MP3 recordings of every poem Knight read at a memorable February 25, 1986 reading. The introduction to the reading was given by Gwendolyn Brooks herself — she who had long been an encourager of Knight. “Don’t let us lack hard rock,” she says at one point in this intro, addressing herself directly to Knight. She reminded her audience of a poem Knight had written in response to her very early poem, “truth,” in which she (as she reminded us in ‘86) had equated truth with sunshine. And Brooks read the opening lines of Knight’s “The Sun Came,” and then invited Knight up to the podium with the command to “open your mouth.” Open it he did, Etheridge Knight did, and along the way performed “The Sun Came” himself.

On PennSound’s Etheridge Knight page we offer single downloadable MP3 recordings of every poem Knight read at a memorable February 25, 1986 reading. The introduction to the reading was given by Gwendolyn Brooks herself — she who had long been an encourager of Knight. “Don’t let us lack hard rock,” she says at one point in this intro, addressing herself directly to Knight. She reminded her audience of a poem Knight had written in response to her very early poem, “truth,” in which she (as she reminded us in ‘86) had equated truth with sunshine. And Brooks read the opening lines of Knight’s “The Sun Came,” and then invited Knight up to the podium with the command to “open your mouth.” Open it he did, Etheridge Knight did, and along the way performed “The Sun Came” himself.

Is Knight’s poem a rejoinder or counterargument to Brooks’ “truth” in any sense? There is no easy answer to this question. For this episode of PoemTalk Al Filreis gathered Tracie Morris, Josephine Park, and Herman Beavers to talk through the relationship between the two poems and between these two poets. Enabled by Tracie’s sense of the lived authority of Knight’s voice (“the Joe Williams of modern poetry”), by Jo’s close reading of his performed meter, and by Herman’s  attention to the jailed figure of Knight, we soon realize that Brooks invites a dialogue by way of a key religious trope, and that Knight has responded by figuring Malcolm X as Jesus Christ. Summoned by Brooks to testify about Jesus, Knight associates Malcolm with the end of darkness. Christian regret (we did not sufficiently know him until after death) sparks Knight’s angry, sad, sorrowful expression of our having “goofed the whole thing” — that our ears should have been, but weren’t, equipped to hear the “fierce hammering.” The sun comes. So Malcolm comes. Did the light of each or either reach the cell of the speaker? It seems that it did not (although the poem itself is our only evidence otherwise). Who comes? Mal (evil, danger, etc.) comes. (The way Knight emphasizes the repeated “MALcolm” makes this double sense clear.)

attention to the jailed figure of Knight, we soon realize that Brooks invites a dialogue by way of a key religious trope, and that Knight has responded by figuring Malcolm X as Jesus Christ. Summoned by Brooks to testify about Jesus, Knight associates Malcolm with the end of darkness. Christian regret (we did not sufficiently know him until after death) sparks Knight’s angry, sad, sorrowful expression of our having “goofed the whole thing” — that our ears should have been, but weren’t, equipped to hear the “fierce hammering.” The sun comes. So Malcolm comes. Did the light of each or either reach the cell of the speaker? It seems that it did not (although the poem itself is our only evidence otherwise). Who comes? Mal (evil, danger, etc.) comes. (The way Knight emphasizes the repeated “MALcolm” makes this double sense clear.)

But back to the question of possible rebuke. Herman hears some counterargument in Knight, Tracie less so. One of those rare disagreements on PoemTalk. The discussion among all four is at its most interesting here, and there’s some good talk about Brooks’ sheer power and pull as a poetic personage. Finally, Herman summarizes this segment of the discussion as follows, speaking in Knight's voice: “I’m honoring your influence by taking it in a direction that you would not take it.” It = the problem of the instance of the sun; the possibility of radical opportunities.

December 29, 2010

Herman Beavers, the tundra of yes

A review of 'Obsidian Blues'

Obsidian Blues, to quote Herman Beavers quoting Ralph Angel, is itself “a still life and a way to get home again.” The poems in this powerful collection often present still lives of stilled lives. The speaker can see “Apples. / The way the light / betrays them” in a poem,“Obsidian Blues 43,” about a guitarist whose stringy wail (“strings judding like a systolic ghost swaggering”) sings a song of variation that reqpeatedly requires renaming. One such tentative title is “Still Life with Guitar and Heartstrike”; another is “Landscape with Skull and Banjo.”

On September 9, 2017, at the Kelly Writers House, Herman Beavers read poems from his new book, Obsidian Blues. HERE is a link to the video recording of the event, and HERE is a link to the audio-only recording.