'Authentic texts'

Translation is trade without commerce

Displacement. Chosen and unchosen migrations. Free and unfree trades. How displacement is also a kind of placement, an unfamiliar vantage point from which to renegotiate terms, terrains, parameters, possibilities. Translation is willing and willful displacement. In moving a word, phrase, line, sentence, stanza, paragraph, idea, framework from the space of one language to the space of another, something utterly transformed is created, and something that is still very deeply (though not essentially) the same as what it was to begin with (which was not immobile in the first place). Alchemy

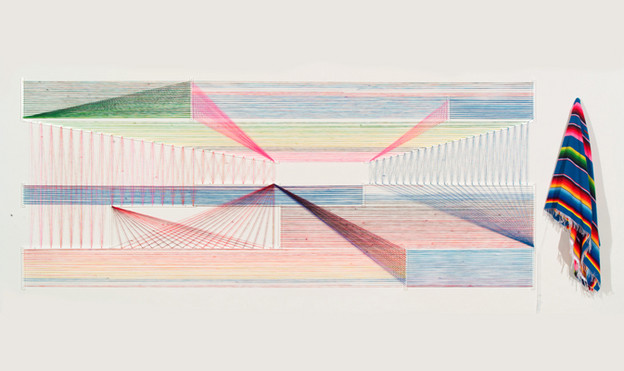

In a conversation, Sesshu Foster recently referred to the space of translation as “no-man’s land.” I’d agree and also add the idea of “every person’s land,” in the sense that no one and everyone might belong there, or perhaps that the very concept of “belonging” no longer pertains—the question is one of moving through space, rather than claiming it. Of using the terms imposed upon us (as Adrián Esparza uses the typical Mexican blanket sold to tourists, for example) to subvert the intentions of their imposition. To unknit the weave that would bind us.

I often feel as if I haven’t truly read a text until I’ve translated it—that the perspective I gain from getting inside the language, structures, imagery and rhythms of the text is not accessible through any other process of reading. I wouldn’t necessarily have thought I wanted to get inside the text of the NAFTA document, given that my actual wish is that it not exist at all in its current form. Yet it is always useful—perhaps urgently so—to consider how language structures are deployed to enforce social and economic structures. The process of translating Hugo García Manríquez’s re/vision of that document has illuminated some of the nuances of this reality, while reminding me yet again how crucial it is to find ways to get inside the hollows or fissures between words and re-imagine how to use those spaces as sites of criticality and resistance.

Magda Sayeg, "Mexico City Bus Project"

I wonder if knitting fitted covers for structures illuminates a different or more nuanced understanding of those structures in a congruent way?

(Note to readers: In some browsers, it's not possible to scroll through Hugo's texts as I'd intended. Please click here to read Hugo's text in Spanish, and here to read my translation of Hugo's text in to English, and please pardon the disruption.)

Hugo García Manríquez, "Anti-Humboldt" (español)

Hugo García Manríquez, "Anti-Humboldt" (english)

At one point in the process of translating the text, Hugo and I had this brief exchange (I'm in blue; he's in black):

Parece que en español dice “libre” donde dice “extranjero” o “ajeno” en inglés... hm...

Extraña situación, verdad? Creo que esa zona libre esa unknown quantity flota libre (extranjera) en el documento. Al igual que muchas otras.

It seems that in Spanish it says “free” where it says “foreign” in English... hm...

A strange situation, right? I think that this free zone this unknown quantity floats free (foreign) in the document. Just like many others.

In a later post I’m planning to provide an alternate translation of Hugo’s NAFTA piece—either a more literal translation or a less literal one, depending on your perspective. More literal in the sense of attempting to recreate the meanings (denotative and connotative) and reverberating proximities in Hugo’s word choices, but less literal in not reproducing his process, or the actual language of the original document (which pre-exists my translation, of course). The act of translating Hugo’s process (the meaning of the acts) rather than his language (the meaning of the words) re-invigorates the question of what writing is, in any given instance (and it’s unlikely any two instances would reproduce the same answer to that question), and what is actually manifested by the deceptively simple term text. I’m also reminded of Patrick Greaney and Vincent Kling’s astonishing translation of Heimrad Bäcker’s wonderfully horrifying book transcript, culled entirely from Nazi administrative texts and a few excerpts from the Nuremberg trials. It’s fascinating to read transcript alongside Charles Reznikoff’s Holocaust (some of which you can hear aloud here); the two books together are an amazing tool (teaching-wise or whatever-wise) for thinking about approaches to documentary poetics, how to address large-scale atrocity via meaningful artistic interventions, process-based writing, practices of appropriation, and writing as translation.

Meanwhile, the process of translating Hugo’s renegotiated NAFTA document led to the following conversation, where I’ll print Hugo’s comments in black and my own interjections in blue.

*

It’s interesting, the “decisions” behind each word I chose in Spanish don’t always get “translated”—they don’t manifest in English. Political re-magnetization, once the words are isolated in Spanish, isn’t present in the same passages in English, it seems to me. Undoubtedly it’s there in other moments.

In my experience, the “re-magnetization” that occurs in the transit between languages (which is also inherently a transit between cultures, and hence between distinct if not easily definable spaces of resonance and connotation) hardly ever (or never?) works the same way in one language as it does in another. It’s not that this newly-charged repositioning doesn’t manifest, it’s that it manifests differently. Which is precisely why I think translation is so necessary. A tangible manifestation of difference, evidence of the effects of re-positioning. And aren’t we all repositioning, in some way or another, all the time? Trans positions.

There’s an odd article, Article 2206, in all three versions of the NAFTA document, titled “Authentic Texts,” which reads: “The English, French and Spanish texts of this Agreement are equally authentic.”

I wonder what this means. (Me he preguntado qué quiere esto decir.) And it leaps out at me that in Spanish, as you’ll surely recall, we use the phrase “And what does that WANT to say?” (¿qué QUIERE esto decir?) when we ask about something we don’t understand, but especially when we seek an explanation of a word in another language. As if translation were merely a desire, an approach, but NOT the fulfillment of a term’s meaning.

Perhaps for “Authentic,” we might understand “Specific,” “Untransferrable,” “Irreplaceable”? The magnetization that envelops language and the history of that language and the history of the country in question (which should say, the questioned country), are untransferrable, untranslatable. Perhaps for this reason, the words that survive in Spanish float indifferently within the text in English, because they are merely an approach. And surely the case would be the same, fueran las cosas al revés...

Or perhaps the term “authentic” refers to an enforced sameness, such that no matter what the text actually says—the denotations or connotations of the words utilized to express the enforced difference a trade agreement of this sort represents (separate and UNequal)—the text is considered, officially, to be authentically the same as itself no matter what.

...strange expressions like “los zócalos submarinos” with such specific resonances for a city like D.F....

It becomes (translates to, though authenticity would deny that transfer): the submarine shelf. A rather surrealist image, in any case. With a certain fascination, but lacking in specificity.

The heart of a city under the sea... A beautiful, and in some way accurate, image, particularly when I consider Los Angeles, whose public face (botox-blotched and boob-job-blemished) is so very distinct from my bicycle-centric experience of the many cities that make up this city.

The zócalo is the central plaza in Mexico City—in a very real and at the same time utterly non-fixed sense, it is one of many hearts of civic life in the city (and is a place of many transformations, alchemical and otherwise). Many, many important activities take place there, from government meetings to large-scale protests, from religious services to archeological explorations, from museum visits to free outdoor concerts and salsa-dancing contests, from transit to loitering, from street vending to pawn-brokering. “The submarine shelf” hardly expresses these resonances in English; shelves are useful, to be sure, but hardly carry the cultural and political weight of a space like the zócalo. Every city and town in Mexico, by the way, has a zócalo—so while the term means something very specific in the context of Mexico City, it also resonates more widely within Mexican consciousness.

There’s really no way to translate this idea/reality and generality/specificity of the zócalo into English. There is no term that combines “Washington Mall” with “town square.” And this leads me to consider the oddness of the term “Mall” in the context of the capital in any case... or perhaps the resonance with consumerism isn’t odd at all, given the workings of capital in the capital and elsewhere.

From the beginning, I thought of the word Limbo for these spaces my project was opening, because it’s so close to Limbs (in English anyway—not so in Spanish, where “limbo” is a direct cognate but “limbs” (miembros) are more kin to members than in-between spaces)—and creates that idea of appendices or appendages (which occur throughout the Agreement, those unattached pieces, like a mutilated body).

In the notes accompanying my project with the NAFTA document, I added this, which I think is relevant:

Instead of writing “like a poet,” to read like one: creating hollows, pauses, holes, limbos

(“Limbo,” sonically bordering limbs, in English: “appendages” (apéndices), “extremities” (extremidades))

From within the hollows of reading itself, unintelligibility emerges by turns, from within that transit. That opacity isn’t a lack of meaning, but rather its compliment. “To mean is to fall.”

Regarding the last line of his letter, which was in quotes, I asked Hugo where the phrase originated. He wrote:

Thanks for noticing that! Here I’m reworking and appropriating something the Argentinean philosopher Óscar del Barco said in an interview. (By the way, del Barco is the Spanish-language translator of Derrida’s Of Grammatology).

Here’s a transcription of the fragment of the interview I included in my first book:

“Isn’t what you’re saying too poetic?”

“I don’t know any other way to say it.”

“You’re naming.”

“Yes, but I don’t want to refer to individuals, but rather to experiences, to occurrences.”

“A soul?”

“No.”

“A body? What do you mean?”

“That everything should be allowed to fall: body, spirit, time, eternity, instant, being, god, transcendence.

“What do you mean by “fall”?

“Fall means fall.”

This last phrase is what I’ve reworked. If falling can only be explained in the very action of falling (i.e. only in falling do we understand what falling means), something similar might be said of meaning (only in meaning do we “understand” what meaning means). And contradictorily, there is a sort of “excess” in the act of writing poetry—an excess that can do nothing but allow itself to fall. I don’t know how to elaborate on this. Perhaps via a dream I had some time ago. In my dream, while I was talking with some other people, I proposed a comparison between Violence and Poetry, because both were “excesses”—one of power, the other of meaning. Both were an overtaking of something. In the dream I believed this to be true. And when I woke up, I felt I had understood something.

In my first book, No oscuro todavía (Not Dark Yet), I use an extraordinary quote from Óscar del Barco as an epigraph:

“What’s deceptive is the fixedness of language. The fact that in language floats our identity, continually, as a pole of all constitution prevents us from understanding that identity is a phantasm that chaos coagulates as language.”

Since then, that epigraph has been “company and measure,” in this new project as well, now that I think about it.

Company and measure, indeed. (Thanks, Creeley!) Perhaps that’s as accurate as any articulation of what translation might be.

Trans positions