Artaud and the surrealists

Artaud joined the Surrealist movement in October 1924, just as their journal was launched and André Breton’s first manifesto appeared. Artaud was a frequent contributor to the journal, La révolution surréaliste, and edited several issues. He also managed the Bureau of Surrealist Research. Like many of the original members, Artaud was expelled from the group by Breton. This happened around 1926.

Site of the Bureau of Surrealist Research, 15 rue Grenelle, Paris

In many ways Artaud’s beliefs meshed well with those of the Surrealists. They shared a capacious definition of poetry. Robert Motherwell, who was a part of the American contingent after the war, explains that “in the eyes of André Breton, a writer truly committed to surrealist principles was indeed a ‘poet,’ whatever the genre of writing. Surrealists were poets by definition. Surrealism was a lyric behavior, with all that it implied of moral principles, unbourgeois situations, and continuous creation.”[1] Artaud’s first creative impulse was poetry—he had, by this time, published his first book, Backgammon in Heaven—and all of his work was a continuation of this initial poetic impulse.

And while Artaud started in poetry, throughout his life he shifted mediums in an unabated search for liberatory expression; he moved from poetry to theater to travel to drawing and back to poetry. This poetic through-line matches the Surrealist beliefs about the connection between texts. In the same interview with Mary Ann Caws, Motherwell states: “The surrealist poets as such rarely made any separation between their texts. Robert Desnos, for example, considered all his poems part of one great poem—just as the great symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé had considered all writing part of one book.”[2] For the Surrealists, every boundary should be transgressed: that of genre, that of rational thought, and those that separate the inside world from the outside world.

In André Breton’s first "Surrealist Manifesto," he proclaims,

in this day and age logical methods are applicable only to solving problems of secondary interest. The absolute rationalism that is still in vogue allows us to consider only facts relating directly to our experience. Logical ends, on the contrary, escape us. It is pointless to add that experience itself has found itself increasingly circumscribed. It paces back and forth in a cage from which it is more and more difficult to make it emerge. […] Under the pretense of civilization and progress, we have managed to banish from the mind everything that may rightly or wrongly be termed superstition, or fancy; forbidden is any kind of search for truth which is not in conformance with accepted practices.[3]

The Surrealists wanted to replace rational thinking with a complete freedom that would come from the unconscious. Artaud, too, was looking for a revolutionary break from rational thinking.

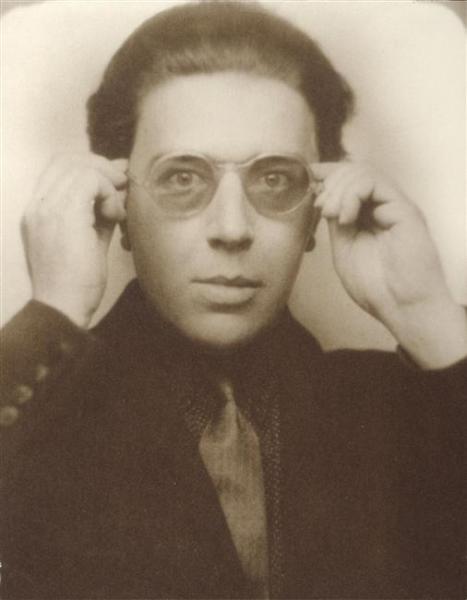

André Breton, 1924

Motherwell described this new way of thinking as a “capillary tissue,” whose role was, to quote Breton, “to guarantee the constant exchange in thought that must exist between the exterior and interior worlds, an exchange that requires the continuous interpenetration of the activity of waking.”[4] Artaud uses this same metaphor of inside/outside world to accuse the Surrealists of missing the point. In “Man Against Destiny,” a lecture Artaud delivered during his trip to Mexico in 1936, Artaud dismisses Surrealism with a detailed critique of Marxism’s failings. The Communist revolution, although “concerned with thought,” doesn’t allow thought its full dynamic movement.[5] Artaud insists that scientific experiment divorces existence from its dynamism. Thought, he asserts, is a combination of three movements: a movement inward, a movement outward, and a rotational movement. Scientific experiment—rational though—means “to look at a landscape through the small end of reality.”[6] There is a parallel challenge with Marxism, which “approaches [thought] from the viewpoint of experiment, that is, from the external world of facts.”[7] Artaud explains that “a preoccupation with the external functions of Man leads one away from a profound understanding of Man. And there is a whole world in the mind. The Communist revolution ignores the internal world of thought.”[8] In Artaud’s estimation, then, the Surrealists latched onto a theory which ran contrary to their central and initial philosophical tenets.

Both Artaud and the Surrealists attack rational, Western thought. In the first “Manifesto of Surrealism,” Breton describes this aversion: “the realistic attitude, inspired by positivism, from Saint Thomas Aquinas to Anatole France, clearly seems to me to be hostile to any intellectual or moral advancement.”[9] But Artaud argues that Marxist thought’s emphasis on external material is a part of the problem: “To arrest thought from the outside and to study it with regard to what it can do is to misunderstand the internal and dynamic nature of thought. It is to refuse to perceive thought in the movement of its internal destiny which no experiment can capture.”[10]

Even further, Artaud sets Marxism against poetry. He declares: “I call poetry today the understanding of this internal and dynamic destiny of thought.”[11] He goes on to say that “poetic understanding is internal, poetic quality is internal. There is a movement today to identify the poetry of the poets with that internal magic force which provides a path for life and makes it possible to act upon life.”[12] For the Surrealists poetry was synonymous with Surrealism, which is why in the beginning of his essay, Artaud makes a point to differentiate Surrealism’s beginnings from where it eventually headed. He describes “that hunger for a pure life which Surrealism was in the beginning” and maintains that this initial impulse “had nothing to do with the fragmentary life of Marxism.”[13]

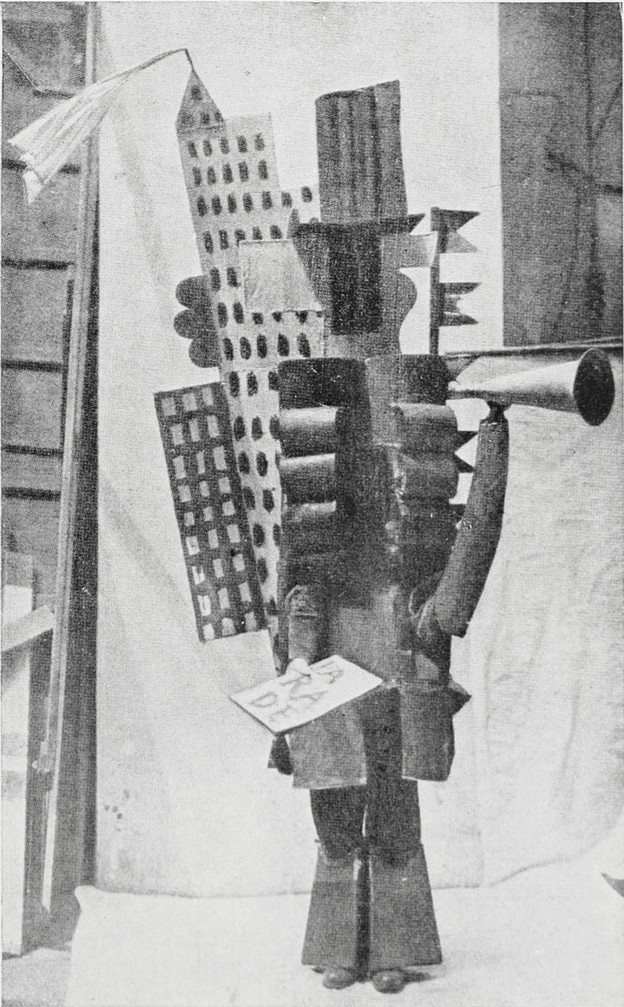

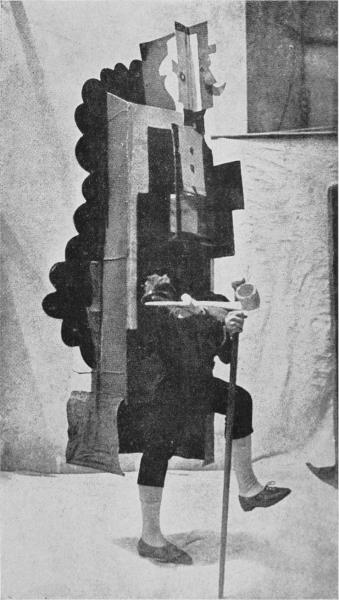

This fundamental disagreement between Artaud and his Surrealist companions manifested in Artaud’s use of the theater as a part of his poetic practice. This is ironic because the term “surrealism” was coined by Guillaume Apollinaire in reference to a stage performance—the ballet “Parade,” performed in 1917. Jean Cocteau and Eric Satie composed the scenario and music, and the sets and costumes were designed by Pablo Picasso.

Pablo Picasso's costume design for Parade, 1917

While Artaud was making a name for himself as a writer, he was simultaneously pursuing an acting career. Artaud’s uncle, Louis Nalpas, was involved in the film industry and helped Antonin get acting jobs. Through his uncle Artaud met Charles Dullin, and in 1922, two years before Artaud joined the Surrealists, he played Tiresias in a production of Antigone. Jean Cocteau adapted the play, Charles Dullin directed it, and Pablo Picassso created the sets. Coco Chanel made the costumes and Arthur Honegger composed the music. Stephen Barber reports that “it was a great success, despite a demonstration on the opening night by the Surrealists, who despised Cocteau for his contacts with Parisian high society.”[14] As the Surrealists embraced Marxism more and more, pursuits like the theater became less and less tolerable. Their differences came to a head with the Alfred Jarry Theatre, a collaborative project Artaud was trying to get off the ground. Stephen Barber characterizes Breton’s reception of the Alfred Jarry Theatre as “acrimonious” and suggests that his objections “stemmed largely from the view that theatre was intrinsically bourgeois and profit-orientated.”[15] While the Surrealists didn’t stay with the Communist Party forever, this foray was long enough to expel Artaud from the Surrealist group.

1. Robert Motherwell qtd in Mary Ann Caws, “Preface: Surrealist Gathering,” Surrealist Poets and Painters: An Anthology, (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2001,) xxviii.

2. Robert Motherwell qtd in Mary Ann Caws, xxviii.

3. André Breton, translated by Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane, Manifestoes of Surrealism, (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1969), 9-10.

4. André Breton qtd in Mary Ann Caws, xxviii.

5. Antonin Artaud, “Man Against Destiny,” Antonin Artaud Selected Writings, Ed. Susan Sontag, Tr. Helen Weaver, (New York: Farrar, Strauss, Giroux 1976), 361.

6. Antonin Artaud, “Man Against Destiny,” 360.

7. Antonin Artaud, “Man Against Destiny,” 361.

8. Antonin Artaud, “Man Against Destiny,” 361.

9. André Breton, translated by Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane, Manifestoes of Surrealism, (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1969), 6.

10. Antonin Artaud, “Man Against Destiny,” 362.

11. Antonin Artaud, “Man Against Destiny,” 362.

12. Antonin Artaud, “Man Against Destiny,” 362.

13. Antonin Artaud, “Man Against Destiny,” 357.

14. Stephen Barber, The Anatomy of Cruelty: Antonin Artaud: Life and Works, (np: Sun Vision Press, 2013, 18.

Language and its double