Antonin Artaud's 'Contradictions'

Two and a half years before his death, Antonin Artaud declared that he was “born otherwise, out of my works and not out of a mother.”[1] This assertion appears in a letter to Henri Parisot, Artaud’s editor at Editions Flammarion, who was soon to publish A Voyage to the Land of the Tarahumara. The letter to Parisot was intended to supplant an earlier preface to the book in which Artaud had stated his conversion to Christianity. Artaud explains,

I was idiotic enough to say that I had been converted to Jesus christ, whereas christ is the thing that I have always most abominated, and this conversion was merely the result of a terrible spell which caused me to forget my own nature and to swallow in the name of communion, here at Rodez, a terrifying number of hosts intended to keep me for as long as possible and if possible eternally in a being which is not my own. This being consists in rising to heaven in spirit instead of descending further and further into hell in the body, that is, into sexuality, which is the soul of all life. Whereas christ carries this being off into the empyrean of clouds and gases where he has been dissolving since eternity. The ascension of the so-called Jesus christ 2000 years ago was merely a rise into an infinite vertical in which he one day ceased to be and in which all that remained of him fell back into the sexual organs of all men as the basis of all libido. Like Jesus christ there is also the one who never descended to earth because man was too small for him and who remained in the abysses of the infinite like a so-called divine immanence who tirelessly, and like a buddha of his own contemplation, waits until the BEING is sufficiently perfect to come down and enter his body, which is the base calculation of a coward and a sluggard who did not want to suffer being, all of being, but let it be suffered by another only to banish this other, this sufferer, and send him to hell when this hallucinate of suffering would have transformed the reality of HIS suffering into a paradise, all prepared for that ghoul of sloth and villainy known as god and Jesus christ. I am one of these sufferers, I am this principal sufferer into whom god means to descend after I am dead but I have 3 daughters who are other sufferers, and I hope that you are also one in your soul, Henri Parisot, for next to god and christ there are angels who claim the same right as he and have always claimed to take over the consciousness of every creature born, although they believe themselves to belong to the inborn.[2]

Artaud’s writings are often fever-pitched, serpentine, and contradictory. In this passage Artaud argues that he does not believe in Jesus Christ. The Christian myth is turned on its head here, but it isn’t completely dismissed. Instead, Artaud takes on the position of Christ—the one who will suffer in order to save others. Artaud is not saving his fellow man, however; he’s suffering so that God doesn’t have to endure the pain of a body. He reasons that God will inhabit his frame (though he also accuses God of being a coward for waiting until Artaud’s suffering has passed through like a purifying fire.) What’s more, Artaud’s is not the only body that will become a host. He knows of at least three other sufferers and a line of angels and other beings (including Christ) who are waiting for a corporeal door to open. At the same time that Artaud dismisses Christ as the Savior, then, he also invokes Jesus within his personal cosmography. This contradiction—invoking the figure he has just renounced—may seem more like a small discrepancy than an outright opposition, but it points to a pattern of fluid discrepancies in Artaud's writing. Artaud's schema is constantly moving.

His letter becomes a larger contradiction when juxtaposed with the one just before it in Antonin Artaud Selected Writings. Written seven months prior and addressed to Artaud’s sister, Marie-Ange, the first letter confesses a renewed faith in God and retracts those sentiments in his seminal book, The Theater and Its Double, which Artaud acknowledges are not “specifically antireligious,” but which were “written in a period of disbelief and estrangement from God and this can be felt in more than one passage.”[3] Artaud confesses this to his sister in order to explain his not having sent her a copy of the The Theater and Its Double. He promises that once he has “perfected a sample of a literature […] capable of uplifting the heart and soul of the reader, I shall send you this, and you will be grateful to me because you will find it beneficial for yourself and your children.”[4] In the span of little over half a year, Artaud moves from an embrace of Christianity to a wild renunciation of Christ and a reconfiguration of the world with his own suffering at its center. And herein lies one of the biggest challenges of reading Artaud.

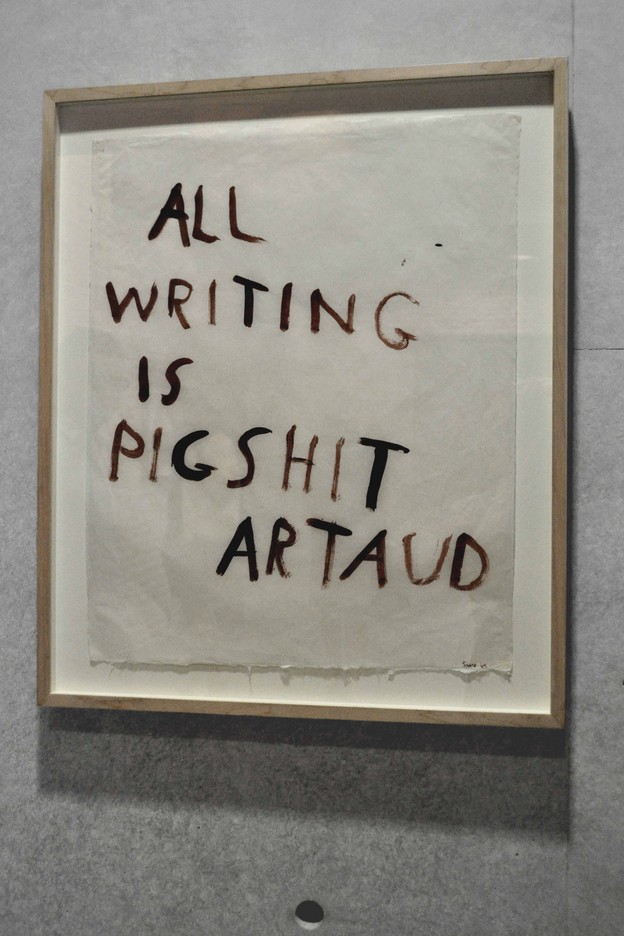

The challenge in recounting the contents of this letter to Parisot, or to talk about Artaud at all, is that a retelling must necessarily linearize the disparate threads of Artaud’s logic. To make sense we must make story. At the center of Artaud’s life was the desire to transcend the constraints of reality, to push toward a revolution in human consciousness, which means Artaud held an impossible aim. His pursuit of this aim was relentless. His complete works—now 26 volumes—includes essays, letters, poems, plays, manifestoes, and genre-bending work, like “The New Revelations of Being,” which indexes notes from a tarot reading. Later in life he took up figure drawing. He was an actor—both on stage and on screen. The breadth of his artistic pursuits demonstrates the hunger of his search. The facility with which Artaud moved between genres, sometimes within the same piece of writing, highlights the extent to which his work folded together (sometimes contradictory) ideas and theories into a complete (albeit fractured) whole. It is difficult to represent this whole without replicating it. His work resists paraphrase in the way poetry does. To explain away his contradictions or make neat sense of his mental wilderness would flatten the work.

Antonin Artaud, 1926

Still, it is possible to judge Artaud’s work—his contradictions, paradoxes, and wild exclamations—through a normative lens. That is to say, it would be easy to identify contradictions in Artaud’s work and dismiss them as manifestations of his mental illness. Artaud spent much of his fourth decade in institutions. The letter to Henri Parisot was written from the asylum at Rodez and likely refers to electroshock therapy when Artaud says, “this conversion was merely the result of a terrible spell which caused me to forget my own nature and to swallow in the name of communion, here at Rodez, a terrifying number of hosts....”[5] But to meet Artaud on society’s terms instead of his own would miss the point. Alexandra Lukes, an Assistant Professor of French at Trinity College in Dublin, constructs an argument about Artaud’s nonsense language which applies to his larger body of work as well.

In "The Asylum of Nonsense: Antonin Artaud's Translation of Lewis Carroll," Lukes asserts that Antonin Artaud’s nonsense language requires the reader to examine the process of meaning-making itself—“the very process of understanding him, ourselves, and others”—if the reader is to understand the text, because “it implies coming to terms with the suffering inherent in any relationship to language and understanding to what extent the process of carving out one’s space in language is precariously balanced between the need for invention and the risk of disarticulation.”[6] To support her position, she first introduces two common readerly responses to Artaud’s nonsense words: either one tries to decipher from the nonsense some “esoteric” meaning or one disregards the ungrammatical, non-semantic parts of the text entirely and focuses instead on the recognizable language. Either approach will only skirt the surface and will miss a major thread of the work. Artaud’s writing is not just demonstrating his alienation by performing it in language, it’s asking us to investigate how we relate (or don’t) to others through language. The contradictions in his texts, these disparate threads, ask us to explore how we relate to and configure our selves. To what extent does internal contradiction challenge our idea of selfhood? What does it mean to live in contradiction?

For Antonin Artaud, living in contradiction meant that he didn’t exist before he created himself through his work. His writing and art were a form of survival. He was born out of his own pain. Antonin Artaud’s suffering was real, and his experience in a body, including the suffering associated with his physical and mental ailments—compounded by a lifelong addiction to narcotic painkillers—constitutes a central concern in his work.

Antonin Artaud’s work—the body of work as a whole—holds a proliferation of central concerns. In the letter to Henri Parisot, we see one of Artaud’s quintessential stances: hyper-negation. Artaud refused to accept common belief systems and instead fused his own system. He rejected the unification of ideas in writing; he rejected Christianity; he rejected Western logic; he rejected Surrealism; he rejected authority. As a result of his subversive spirit, Antonin Artaud sent up the big middle finger at every opportunity. He refused to accept the world as it was. His refusal stands as a revolutionary and generative, creative act in the same vein as CAConrad’s first book. Conrad explains, “The title of my first book with the middle finger cover is Deviant Propulsion. My idea behind the title is that it is the deviants who propel the culture forward whether everyone is ready or not! You ask what is my vision for queer poetry and I say it is something written by poets whether they are homosexual, bisexual, heterosexual, or asexual, but poets who are willing to take on that deviant queerness and confront the madness because the madness is real.”[7] Antonin Artaud was one of the deviants. He confronted the madness with his own madness.

1. Antonin Artaud, “Letter to Henri Parisot,” Antonin Artaud Selected Writings, Ed. Susan Sontag, Tr. Helen Weaver, (New York: Farrar, Strauss, Giroux 1976), 442.

2. Artaud, “Letter to Henri Parisot,” 442.

3. Antonin Artaud, “Letter to Marie-Ange Malausséna,” Antonin Artaud Selected Writings, Ed. Susan Sontag, Tr. Helen Weaver, (New York: Farrar, Strauss, Giroux 1976), 440.

4. Artaud, “Letter to Marie-Ange Malausséna,” 440-441.

5. Artaud, “Letter to Henri Parisot,” 442.

6. Alexandra Lukes, “The Asylum of Nonsense: Antonin Artaud’s Translation of Lewis Carroll,” The Romantic Review, Volume 104, Numbers 1-2, 125.

7. Conrad, CA, The Library of Congress* Censored Interview, CAConrad interviewed by Jasmine Platt, (New Jersey: Bloof Books, 2016), 12.

Language and its double