Poem by Abu Sakhr as transmitted by al-Sukkari & translated by David Larsen

It gives me great pleasure to publish David Larsen's translation & introduction of this excellent 8 century poem with 10 century comments from the classical, though unhappily too little known (at least in Euro-American lands) Arab literary tradition. See also his translation of al-Qali's version of the same poem on Nomadics blog.

*

It is natural to associate ghazal poetry with the tribe of ‘Udhra. ‘Udhra was the tribe of Jamīl Buthayna (d. 701 CE), the lovesick virtuoso whose imitators were called after him "the ‘Udhrī poets." Meanwhile, another West Arabian tribe figuring prominently in the history of the ghazal does not receive nearly enough credit. This is the tribe of Hudhayl - a group of pastoralists and beekeepers who, though slow in adopting Islam, were at the vanguard of the Islamic conquest of Africa. They were also famed as poets, and their work was gathered in a tribal register called Dīwān al-Hudhaliyīn (Collected Poems of the Hudhalīs - Hudhalī being the adjectival form of Hudhayl), where some of the earliest ghazals can be found.

One way to begin the ghazal's origin-narrative is with Abū Dhu’ayb al-Hudhalī, who died on campaign in North Africa in the mid-seventh century, probably before Jamīl was born. Renate Jacobi's 1985 article "Time and Reality in Nasīb and Ghazal" (Journal of Arabic Literature, vol. 16, 1-17) makes a persuasive case for Abū Dhu’ayb as a founding figure. Summary of the case requires a quick dive into Classical Arabic poetic form - namely, the form of the qaṣīda, from which the ghazal descends.

The qaṣīda is the earliest form of Arabic poetry to appear in the literary record. This does not mean that the qaṣīda was the earliest form in existence (an impossible notion), but that it was the form most highly prized by rhapsodes and scholars of the eighth and ninth centuries, who were the first to record Arabic poetry in writing. It is an essentially polythematic form, usually divided into three sections. Of these, only the first section's theme is rigorously predetermined. It is called the nasīb ("amatory prelude"), and the poet's separation from the beloved is always its theme. The nasīb is typically followed by a section devoted to travel and praise of the poet's mount, and a section of praise or blame of a particular individual or tribe typically comes at the end.

It was from this high form that the more popular form emerged in the seventh century. Jacobi describes the early ghazal as an isolation of the nasīb from the qaṣīda's subsequent themes, resulting in a monothematic poem. And with that, the Arabic love poem came into its own - a deceptively simple form, deriving from a deceptively composite one. In the observable history of Arabic poetry, the development of the ghazal was the first formal innovation. In the West, the better-known type of ghazal is a latter-day Persianate form built around verse-end refrains - a structure quite external to the Classical Arabic ghazal, which is recognizable by the dedication of its content to erotic themes.

Abū Ṣakhr came a generation after Abū Dhu’ayb. The most salient detail in his biography would be the time he did in the dungeons of the Anti-Caliph. The Anti-Caliph was a frustrated nobleman of Quraysh (the Prophet Muhammad's tribe) named ‘Abd Allāh ibn al-Zubayr, whose occupation of Mecca from 683 until his defeat in 692 constituted the first civil war in Islam. (Seen in this connection, Jerusalem's Dome of the Rock - completed in 692 by the victorious Umayyad Caliph - takes on the character of a victory monument.) In the local resistance to the Anti-Caliph, Abū Ṣakhr proved his martial worth, living on to die around the same time as Jamīl.

A man of few poems (twenty now known), Abū Ṣakhr loved a woman of a nearby tribe named Laylā bint Sa‘d. According to the Book of Songs of Abu 'l-Faraj al-Iṣbahānī, Laylā married instead a man of her people and left their native Ḥijāz for good. Her departure is the subject and the impetus for this poem, whose seventh verse suggests that it was an eastward departure. In verse 22 it is even apostrophized: Fa-yā hajra Laylā ("O departure of Laylā!"), the poet cries. The departure of the beloved's caravan is a staple of the nasīb, and so is the confrontation with the beloved's onetime encampment, which also happens in the poem - twice, apparently, since the first verse mentions two sites that were vacated by Laylā's tribe.

This is a conventional beginning for a qaṣida, and in a conventional qaṣida it would be followed by sections on other themes. By contrast, Abū Ṣakhr's poem sustains the theme of disappointed love, very much like a ghazal all the way to the poem's end. And yet the poem's tenth-century anthologists (Abū ‘Alī al-Qālī and the above-mentioned Abu 'l-Faraj al-Iṣbahānī) do not call it a ghazal, but a qaṣida. I cannot fully explain this designation, other than to suggest that Abū Ṣakhr's poem may have seemed to its early hearers as an undifferentiated form - a hybrid form marked by its qaṣīda-initiating complaint, which is never quite dispelled. Lament follows lament, tending ever toward greater despair, until the consoling marine fantasy of the poem’s end - if, that is, the "‘Ulayya" of verses 29-31 is the same woman called "Laylā" in the rest of the poem.

Very likely she is, as it happens in early Arabic poetry by men that a single woman will be called by different names. Another Hudhalī tribesman of Abū Dhu’ayb's era named Mulayḥ ibn al-Ḥakam calls the same woman "Su‘dā" and "Laylā" within the space of eight verses. In ghazal poetry it happens too, and in this poem it underlines an evident fact, which is that the ghazal, like the qaṣida, is a modular form. If ghazal is truly the monothematic offshoot of a polythematic form, it has its own component sections all the same, marked out by changes of verb tense and address. The verses about ‘Ulayya are the final section. It is almost as if another poem were being quoted, like a tune’ floating through the window just as the present poem is ending.

There is much to be said for this effect, which is known in other modes and forms of Arabic poetry. (In the muwashshaḥa of Islamic Iberia, the effect is built right in.) When one poem ends with a snatch from another poem, it is something to enjoy, as it is here. It is not however verifiable that the effect was intentional on Abū Ṣakhr's part. In al-Qālī's version, these verses do not make up the closing section of the poem but occur as verses 19 through 21 of a 29-verse whole. And in al-Iṣbahānī's version, the verses do not occur at all.

The high degree of variability in Abū Ṣakhr's poem is what motivates the present group of translations, as well as the choice of platform. For screening poems in multiple versions, the internet is a terrific medium, and I am grateful to Pierre for loaning me his. At a click, the reader may jump between the three versions, plus a fourth, derivative poem attributed to Majnūn Laylā.

To my knowledge, there has been no full-length translation of Abū Ṣakhr's poem in any of its variants. Five verses are excerpted by Mahmud Ahmad Ibrahim in Old Arabic Love Poetry (Amman: Dār Āfāq li-'l-Nashr wa-'l-Tawzī‘, 1994), and by Walid Khazendar there is a six-verse excerpt in Traces of Song (Oxford: St. John's College Research Centre, 2005). Another six verses were translated by John Shakespear in the article "Copy of an Arabic Inscription in Cufic or Karmatic Characters," Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland 6:1 (1841), 175. If any English translation of the Majnūn version is out there, I haven't seen it.

One way to begin the ghazal's origin-narrative is with Abū Dhu’ayb al-Hudhalī, who died on campaign in North Africa in the mid-seventh century, probably before Jamīl was born. Renate Jacobi's 1985 article "Time and Reality in Nasīb and Ghazal" (Journal of Arabic Literature, vol. 16, 1-17) makes a persuasive case for Abū Dhu’ayb as a founding figure. Summary of the case requires a quick dive into Classical Arabic poetic form - namely, the form of the qaṣīda, from which the ghazal descends.

The qaṣīda is the earliest form of Arabic poetry to appear in the literary record. This does not mean that the qaṣīda was the earliest form in existence (an impossible notion), but that it was the form most highly prized by rhapsodes and scholars of the eighth and ninth centuries, who were the first to record Arabic poetry in writing. It is an essentially polythematic form, usually divided into three sections. Of these, only the first section's theme is rigorously predetermined. It is called the nasīb ("amatory prelude"), and the poet's separation from the beloved is always its theme. The nasīb is typically followed by a section devoted to travel and praise of the poet's mount, and a section of praise or blame of a particular individual or tribe typically comes at the end.

It was from this high form that the more popular form emerged in the seventh century. Jacobi describes the early ghazal as an isolation of the nasīb from the qaṣīda's subsequent themes, resulting in a monothematic poem. And with that, the Arabic love poem came into its own - a deceptively simple form, deriving from a deceptively composite one. In the observable history of Arabic poetry, the development of the ghazal was the first formal innovation. In the West, the better-known type of ghazal is a latter-day Persianate form built around verse-end refrains - a structure quite external to the Classical Arabic ghazal, which is recognizable by the dedication of its content to erotic themes.

Abū Ṣakhr came a generation after Abū Dhu’ayb. The most salient detail in his biography would be the time he did in the dungeons of the Anti-Caliph. The Anti-Caliph was a frustrated nobleman of Quraysh (the Prophet Muhammad's tribe) named ‘Abd Allāh ibn al-Zubayr, whose occupation of Mecca from 683 until his defeat in 692 constituted the first civil war in Islam. (Seen in this connection, Jerusalem's Dome of the Rock - completed in 692 by the victorious Umayyad Caliph - takes on the character of a victory monument.) In the local resistance to the Anti-Caliph, Abū Ṣakhr proved his martial worth, living on to die around the same time as Jamīl.

A man of few poems (twenty now known), Abū Ṣakhr loved a woman of a nearby tribe named Laylā bint Sa‘d. According to the Book of Songs of Abu 'l-Faraj al-Iṣbahānī, Laylā married instead a man of her people and left their native Ḥijāz for good. Her departure is the subject and the impetus for this poem, whose seventh verse suggests that it was an eastward departure. In verse 22 it is even apostrophized: Fa-yā hajra Laylā ("O departure of Laylā!"), the poet cries. The departure of the beloved's caravan is a staple of the nasīb, and so is the confrontation with the beloved's onetime encampment, which also happens in the poem - twice, apparently, since the first verse mentions two sites that were vacated by Laylā's tribe.

This is a conventional beginning for a qaṣida, and in a conventional qaṣida it would be followed by sections on other themes. By contrast, Abū Ṣakhr's poem sustains the theme of disappointed love, very much like a ghazal all the way to the poem's end. And yet the poem's tenth-century anthologists (Abū ‘Alī al-Qālī and the above-mentioned Abu 'l-Faraj al-Iṣbahānī) do not call it a ghazal, but a qaṣida. I cannot fully explain this designation, other than to suggest that Abū Ṣakhr's poem may have seemed to its early hearers as an undifferentiated form - a hybrid form marked by its qaṣīda-initiating complaint, which is never quite dispelled. Lament follows lament, tending ever toward greater despair, until the consoling marine fantasy of the poem’s end - if, that is, the "‘Ulayya" of verses 29-31 is the same woman called "Laylā" in the rest of the poem.

Very likely she is, as it happens in early Arabic poetry by men that a single woman will be called by different names. Another Hudhalī tribesman of Abū Dhu’ayb's era named Mulayḥ ibn al-Ḥakam calls the same woman "Su‘dā" and "Laylā" within the space of eight verses. In ghazal poetry it happens too, and in this poem it underlines an evident fact, which is that the ghazal, like the qaṣida, is a modular form. If ghazal is truly the monothematic offshoot of a polythematic form, it has its own component sections all the same, marked out by changes of verb tense and address. The verses about ‘Ulayya are the final section. It is almost as if another poem were being quoted, like a tune’ floating through the window just as the present poem is ending.

There is much to be said for this effect, which is known in other modes and forms of Arabic poetry. (In the muwashshaḥa of Islamic Iberia, the effect is built right in.) When one poem ends with a snatch from another poem, it is something to enjoy, as it is here. It is not however verifiable that the effect was intentional on Abū Ṣakhr's part. In al-Qālī's version, these verses do not make up the closing section of the poem but occur as verses 19 through 21 of a 29-verse whole. And in al-Iṣbahānī's version, the verses do not occur at all.

The high degree of variability in Abū Ṣakhr's poem is what motivates the present group of translations, as well as the choice of platform. For screening poems in multiple versions, the internet is a terrific medium, and I am grateful to Pierre for loaning me his. At a click, the reader may jump between the three versions, plus a fourth, derivative poem attributed to Majnūn Laylā.

To my knowledge, there has been no full-length translation of Abū Ṣakhr's poem in any of its variants. Five verses are excerpted by Mahmud Ahmad Ibrahim in Old Arabic Love Poetry (Amman: Dār Āfāq li-'l-Nashr wa-'l-Tawzī‘, 1994), and by Walid Khazendar there is a six-verse excerpt in Traces of Song (Oxford: St. John's College Research Centre, 2005). Another six verses were translated by John Shakespear in the article "Copy of an Arabic Inscription in Cufic or Karmatic Characters," Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland 6:1 (1841), 175. If any English translation of the Majnūn version is out there, I haven't seen it.

♦ ♦ ♦

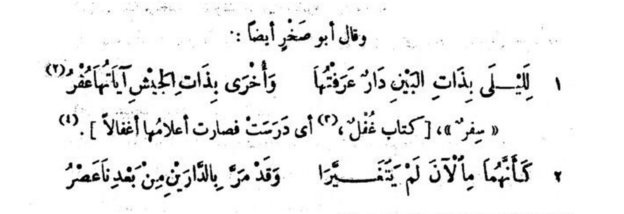

AT DHĀT AL-BAYN I recognized one dwelling as Laylā's,

and another at Dhāt al-Jaysh, with faint brown markings.1

Even now I picture them as if unaltered,

even though both dwellings were long made away with since our time.

Finding them unmade, at a halt by their outline,

I looked away, my eye astream with a flowing tear.

There is evidence in the tear for what I disavow, elucidating

the love I hide, lucid as the moon when it is full.

My fleeting endurance was overcome by her harshness.

It was oppressive to my soul, which fell prey to gauntness.

It was oppressive to my soul, which fell prey to gauntness.

If no more than bygone memory remains of what was

between two lovers, that memory can wear out.

[But] whenever I say: "Now she begins to leave my mind,"

an East wind breezes up at me from daybreak's quarter.

At the mention of her name, my heart quickens

like a rain-drenched sparrow shaking off [its wings].

By the One Who gives cause for weeping and laughter, the One Who

deals death and life, and Whose prerogative it is to give command:

She left me jealous of the wild animals I see in pairs

no clap or shout or flung stone can scatter.

I clave to you, until you said: "He is oblivious to displeasure."2

I paid you visits until you said, "He cannot hold out [much longer]."

Right you are! I am a lovesick fool, assailed

by torments of a heart-pervading passion, or some sorcery.

Beloved are all living things, as long as you may live,

and when a grave contain you, beloved be the dead!

My hands are close to dampness, touching her.

She is [like a pool] ringed with plants of leafy green.3

I make my way to her that she reciprocate [my love];

otherwise, to declare that at dawn we're through.

But no sooner are we alone than I am struck dumb,

abandoned by all cleverness and all reserve.

And I forget what I came to say to her, like the drinker

whose power to remember is robbed by wine,

and [the weightiness of] the affair keeps me from regaining

my balance. As a result, people look at me askance.

Dejected, I go back to wondering aloud, as before:

"When will come the day of hardship's end?"4

There is no good of rapport when likemindedness dies away,

O Laylā, nor in pleasure yielded through compulsion.

I blame you for the days that have elapsed since we were together.

For what we had between us, the nights make no excuse.

O departure of Laylā! You have spared me nothing.

To the anguish of abandonment, you added more.

O love! Let nothing halt the nightly increase

of my ardor for her. Let the Day of Resurrection be my relief.

The evenings we spent at al-Ḥimā - will they never return?

Nor even with the fronds of the flowering mimosa?

Are times gone by never coming back around? Blessings

and thanks to [the Creator]! All that happens is according to Your plan.

The lengths that time went through to come between us

were amazing. Done with what was between us, time stood still,

as if its mutability had not sped the day

[on which] our complications took a leftward twist.

[Time] is deliberate and cares nothing for the vicissitudes

it fires at us, and destiny is on its side.

My love for ‘Ulayya makes me wish we were

aboard a raft at sea, with nothing else between us,5

amid calm waters whose undulating surface no ship crosses,

far from the [high sea's] terrors and green eddies.

that we might bring our souls' anxiety to a carefree end,

and the sea beat back the slanderer we dread.

Notes by al-Sukkarī:

1 [Others transmit the first verse with] sifr, i.e. "obscure writing" [in place of ‘ufr "faint brown"], meaning that the markings have faded and become illegible.

2 A better version of this verse is: "I avoided you, until they said 'He knows not what passion is.'" [Verse eight in Abu 'l-Faraj's version of the poem.]

3 This is Majnūn's verse.

4 The poet's former state is described as either munaḥḥasan, [a passive participle] meaning "confused and unhappy" [thus "dejected" in translation above], or munaḥḥisan, [an active participle] which means the same as mutanaḥḥis: "talking to oneself."

5 Al-ramath [the word for "raft," deriving from Ancient Egyptian rms] is made of timbers lashed together like al-ṭawf [a "floating slab"].

between two lovers, that memory can wear out.

[But] whenever I say: "Now she begins to leave my mind,"

an East wind breezes up at me from daybreak's quarter.

At the mention of her name, my heart quickens

like a rain-drenched sparrow shaking off [its wings].

By the One Who gives cause for weeping and laughter, the One Who

deals death and life, and Whose prerogative it is to give command:

She left me jealous of the wild animals I see in pairs

no clap or shout or flung stone can scatter.

I clave to you, until you said: "He is oblivious to displeasure."2

I paid you visits until you said, "He cannot hold out [much longer]."

Right you are! I am a lovesick fool, assailed

by torments of a heart-pervading passion, or some sorcery.

Beloved are all living things, as long as you may live,

and when a grave contain you, beloved be the dead!

My hands are close to dampness, touching her.

She is [like a pool] ringed with plants of leafy green.3

I make my way to her that she reciprocate [my love];

otherwise, to declare that at dawn we're through.

But no sooner are we alone than I am struck dumb,

abandoned by all cleverness and all reserve.

And I forget what I came to say to her, like the drinker

whose power to remember is robbed by wine,

and [the weightiness of] the affair keeps me from regaining

my balance. As a result, people look at me askance.

Dejected, I go back to wondering aloud, as before:

"When will come the day of hardship's end?"4

There is no good of rapport when likemindedness dies away,

O Laylā, nor in pleasure yielded through compulsion.

I blame you for the days that have elapsed since we were together.

For what we had between us, the nights make no excuse.

O departure of Laylā! You have spared me nothing.

To the anguish of abandonment, you added more.

O love! Let nothing halt the nightly increase

of my ardor for her. Let the Day of Resurrection be my relief.

The evenings we spent at al-Ḥimā - will they never return?

Nor even with the fronds of the flowering mimosa?

Are times gone by never coming back around? Blessings

and thanks to [the Creator]! All that happens is according to Your plan.

The lengths that time went through to come between us

were amazing. Done with what was between us, time stood still,

as if its mutability had not sped the day

[on which] our complications took a leftward twist.

[Time] is deliberate and cares nothing for the vicissitudes

it fires at us, and destiny is on its side.

My love for ‘Ulayya makes me wish we were

aboard a raft at sea, with nothing else between us,5

amid calm waters whose undulating surface no ship crosses,

far from the [high sea's] terrors and green eddies.

that we might bring our souls' anxiety to a carefree end,

and the sea beat back the slanderer we dread.

Notes by al-Sukkarī:

1 [Others transmit the first verse with] sifr, i.e. "obscure writing" [in place of ‘ufr "faint brown"], meaning that the markings have faded and become illegible.

2 A better version of this verse is: "I avoided you, until they said 'He knows not what passion is.'" [Verse eight in Abu 'l-Faraj's version of the poem.]

3 This is Majnūn's verse.

4 The poet's former state is described as either munaḥḥasan, [a passive participle] meaning "confused and unhappy" [thus "dejected" in translation above], or munaḥḥisan, [an active participle] which means the same as mutanaḥḥis: "talking to oneself."

5 Al-ramath [the word for "raft," deriving from Ancient Egyptian rms] is made of timbers lashed together like al-ṭawf [a "floating slab"].

♦ ♦ ♦

Source: Abū Sa‘īd al-Sukkarī (d. 888 CE), Sharḥ ash‘ār al-Hudhaliyīn, ed. ‘Abd al-Sattār Aḥmad Farrāj and Maḥmūd Muḥammad Shākir. Cairo: Maktabat Dār al-‘Urūba, 1963-65 (3 vols.). II.956-9.

Nomadics