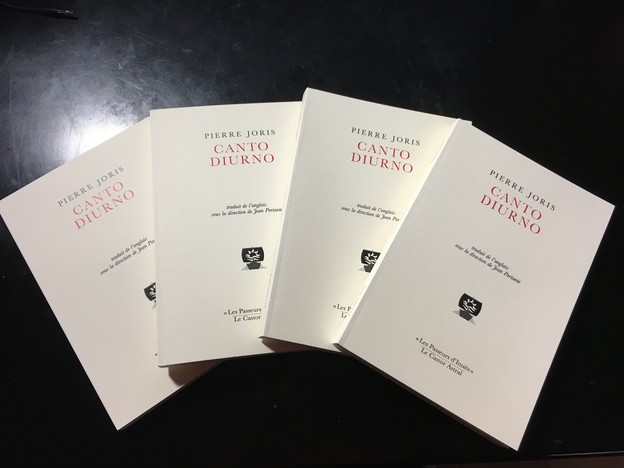

Just Out: 'Canto Diurno'

Selected poems in French

Canto Diurno, my Selected Poems (1972-2012) in French (translations coordinated by Jean Portante) and with a foreword by Charles Bernstein, was published this month by Le Castor Astral in their “Les Passeurs d’Inuits” series. Many thanks to Jean Portante, Jean-Yves Reuzeau, Jacques Darras, and Charles Bernstein for their invaluable contributions.

Here, an extract of Charles Bernstein’s foreword:

Pierre Joris’s Cantos Diurno are never solemn, but they acknowledge the “darkness that surrounds,” as Robert Creeley once put it, that we are always behind our ideals, hopes, aspirations, premonitions, regrets, fears — behind both in the sense of supporting and after, trying to catch up, desperately for the most part, but in these poems not desperate but fortunate, in good humors and with humor.

American poetry is born in second languages, it is our bounty and the secret of our success, if we have any, as much as Samson’s long hair was, once upon a time, the source of his strength. That’s why any attempt to homogenize and assimilate undermines the foundations of our poetics.

Joris’s work is marked by a rare virtue for an American poet: couragio. Everybody is always talking about affect, but no one ever does anything about it. We used to say “lifts your spirits,” but that applies more to Thanksgiving balloons than to verse that challenges. I want a poetry, like this, that changes my mind, puts me in the sway of currents of resistance and change. Where the courage is not just what is said but what is refused: the sanctity of the fixed place, nation or ideal, banner or standard. It’s not just the tyranny of monolingualism that Joris’s verse contests, it’s the tyranny of all forms of monomania: single-mindedness in perspective, style, politics, form, language, identity, desire. “I speak in voices / always always / other people's voices / a thousand mouths.” — We all turned away from virtues when that meant some uppity guy telling us the way we lead our lives is base. What happens if the base speaks in a basso profundo, as in being pro fun with doing more than the done?

Intellectus is not a dirty word. While so much of American poetry culture has run from thick historical context and wit as if they were a European disease, Joris has made a poetry that overthrows the hierarchies but not the minding, tending, churning, plowing, fermenting, and fomenting.

I want to claim Joris as an American poet par excellence, but that is only if we understand “American” as dissolving into the “image nation” (Robin Blaser’s term) — “the city which is syntax” — of non-national possibility. To be neither here nor there, French nor German, Luxembourgish nor Americanische, is to inhabit a provisionality among and between, a toggling that creates a space of rhythmic intensities (“true movement unencumbered”) that confounds binaries and repels axiomatic allegiances. (…)

Joris’s “daily song” is a tracing of a definite but undefined course. The poet recognizes the necessity of a rhetorical address from “the center of my center of nowhere.” Nowhere but still always here, at this long-delayed hearing that determines neither guilt nor innocence but rather makes ways (makes waves) to actualize copability (the ability to cope), which along with adaption, translation, miscegenation, and élan is a guiding force of these beguiling works.

Nomadics