The territorio libre of baseball

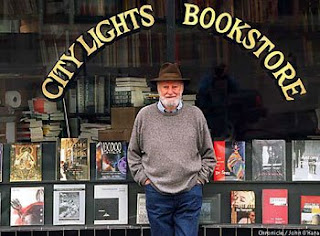

I'm not a huge fan of Lawrence Felinghetti's poems but I've always admired and enjoyed the early figure he cut. The poetry, especially later, is schticky. Well, if you're going to do irreverent liberationist schtick, why not turn the glance at baseball and modernism at once.

I'm not a huge fan of Lawrence Felinghetti's poems but I've always admired and enjoyed the early figure he cut. The poetry, especially later, is schticky. Well, if you're going to do irreverent liberationist schtick, why not turn the glance at baseball and modernism at once.

In "Baseball Canto" Ferlinghetti runs through a crude analogy between the racial and class undersides of baseball and the kind of poetry and poetics that might stand against the exclusivist epic-oriented modernism inherited from Ezra Pound. The analogy only works in a superficial political sense: Tito Fuentes and Willie Mays, beloved by the grungy populace in San Francisco's bleachers, surely hate usury. Poundian modernism becomes an imperialism. It's fast and, as I say, very rough. But funny and fun.

I've made a RealAudio recording of Ferlinghetti reading this poem. If you don't have a RealPlayer on your computer, I apologize. (You can donwload one from Real.com.)

Click here to listen. And here's the poem's text:

Watching baseball, sitting in the sun, eating popcorn,

reading Ezra Pound,

and wishing that Juan Marichal would hit a hole right through the

Anglo-Saxon tradition in the first Canto

and demolish the barbarian invaders.

When the San Francisco Giants take the field

and everybody stands up for the National Anthem,

with some Irish tenor's voice piped over the loudspeakers,

with all the players struck dead in their places

and the white umpires like Irish cops in their black suits and little

black caps pressed over their hearts,

Standing straight and still like at some funeral of a blarney bartender,

and all facing east,

as if expecting some Great White Hope or the Founding Fathers to

appear on the horizon like 1066 or 1776.

But Willie Mays appears instead,

in the bottom of the first,

and a roar goes up as he clouts the first one into the sun and takes

off, like a footrunner from Thebes.

The ball is lost in the sun and maidens wail after him

as he keeps running through the Anglo-Saxon epic.

And Tito Fuentes comes up looking like a bullfighter

in his tight pants and small pointy shoes.

And the right field bleechers go mad with Chicanos and blacks

and Brooklyn beer-drinkers,

"Tito! Sock it to him, sweet Tito!"

And sweet Tito puts his foot in the bucket

and smacks one that don't come back at all,

and flees around the bases

like he's escaping from the United Fruit Company.

As the gringo dollar beats out the pound.

And sweet Tito beats it out like he's beating out usury,

not to mention fascism and anti-semitism.

And Juan Marichal comes up,

and the Chicano bleechers go loco again,

as Juan belts the first ball out of sight,

and rounds first and keeps going

and rounds second and rounds third,

and keeps going and hits paydirt

to the roars of the grungy populace.

As some nut presses the backstage panic button

for the tape-recorded National Anthem again,

to save the situation.

But it don't stop nobody this time,

in their revolution round the loaded white bases,

in this last of the great Anglo-Saxon epics,

in the territorio libre of Baseball.