On Pages

An interview between Robert Sheppard and Joey Frances

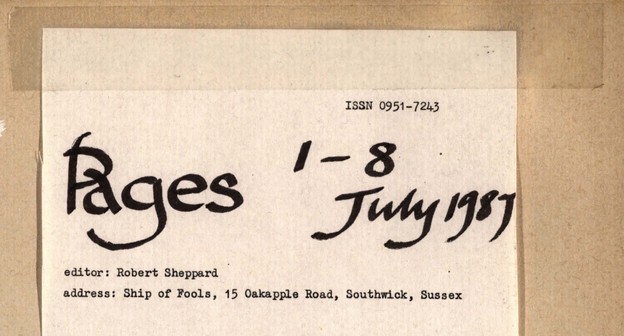

The following interview was conducted over email between Joey Frances and Robert Sheppard in 2017 on the occasion of the Reissues release of Pages, which can be found in Reissues here.

Joey Frances: The first thing I wanted to ask was about the process of putting Pages together. I’ve made some zines in a slightly different context, and small-scale pamphlet- and magazine-making has a big place in the innovative poetry scene — one of the things that was most immediately striking for me when I was scanning the originals is the insight it allowed into the process of making the magazine. I really like how the visual markers of this process show up on the scans. Issue 113–120, which includes drawings by Patricia Farrell, is probably one of the most striking examples, with the pencil lines still visible. I suppose this process was partly led by the properties of the copiers available to you, but the technology and the process is, I think, very different to what I’m familiar with, or how I’d make a zine now. Could you say a bit about how these were put together, what kind of design decisions you were making, and how the methods of production impacted the presentation of the poetry and other work in Pages?

Robert Sheppard: Well, there are the levels of the series, the issue, and the page, I think. I stole the idea from Ian Robinson of Oasis to create a magazine from a limited number of folded pages, in my case, eight, in his slightly more. I’m not sure when I saw Tom Raworth’s In Folio, probably not before I’d started, but I was just getting into what you could do with two sheets of paper, which would be light enough for the basic postage rate and cheap enough to print. I was able to pay for “private printing” at the FE college I worked at in Surrey, and I jumped in almost as soon as I started work there. The idea of publishing two writers seemed obvious: four pages each. (I notice that many online magazines say no more than four pages these days, so it’s an optimum number.) At the level of the page, I decided that I would number the pages sequentially across issues (rather than have issue numbers) to suggest that this was a process as much as a monthly product. Hence the mag’s name. In most cases I asked for camera-ready copy so that I could simply use invisible tape (which, I notice, on the digitalized versions, thirty years later, is no longer invisible!) to paste up the contributions. You notice that Pages 113–120 (the Patricia Farrell–Tom Raworth issue) has Patricia’s original drawings still there: that was an exceptional case, and I knew the drawing would retain its quality if it suffered as few intermediary reproduction stages as possible. We decided to accept whatever quality the college reprographics produced. This was the same principle as with the contemporary Ship of Fools press, which collected the text-image collaborations I made with Patricia; we accepted the result whatever it was. Of course, this was less of a problem with printed text. That issue is unusual in featuring three images.

Frances: It certainly seems in keeping with the spirit of the poetry to allow some element of unpredictability into the production process, and one which to some degree reflects the economics of it as well — I expect on-the-fly use of workplace resources will be pretty familiar to anyone who’s ever made this kind of thing. Another of the most striking pieces of not-strictly-poetry is the cover to Pages 97–104, labelled “Eviction Collage” in the handwritten index which accompanied the set. I’d love to hear a little about the story behind that — both how it came to be included, and if you think it has some contextual function, to imply political or social concerns for the magazine?

Sheppard: If you read my poetry from this time (say, “Coming Down from St George’s Hill”) you will not fail to notice the embattled, even besieged, quality in the tone of voice; the Thatcher years were hard ones for Patricia and me (hopefully not for Stephen, our son, who missed it by being young). I had a supposedly good job at the college, but nowhere to live. We were granted a house in Weybridge by the council, a huge place that literally had empty rooms in it because we didn’t have furniture. But it was on a short lease. The council was worried that tenants would exert their “right” to buy that the Tories had introduced (one of their worst social crimes that we are reaping the results of with little meaningful affordable or social housing today), so we had to be rendered (technically) homeless to be able to get onto the ordinary council house list. I went to court to be declared so (the magistrate gave the council, who were also my employers, a hard time). But it wasn’t lost on me that I was in the same court where Gerrard Winstanley and the Diggers had appeared around 1649 (some of his words are collaged in the design); St. George’s Hill was what is now called a “gated community.” I guess I couldn’t resist slipping that in as the cover; it is social and political content and context but I’m not sure it was done programmatically. Perhaps I should say we used the magazine’s monthly mail out as a chance to propagate some of the Ship of Fools publications that Patricia and I were making, so the magazines are not the whole package, literally. (The recent Ship of Fools Exhibition at Edge Hill University documented some of these.)

Frances: Could you tell me a little more about the poetic context for the magazine? Besides Oasis and In Folio,what else were you reading, or seeing going on at the time, and how did you see Pages fitting with that?

Sheppard: I think magazine editors often say they simply started a magazine because they could, because the machinery was there. I’m thinking that’s the case here. Bob Cobbing is the big influence: if you’ve got the means of production, use them. I was finishing my PhD at this time and knew the history of little magazines in this country (Migrant in the 1950s, Tzarad in the 1960s) and I’d been early enough on the scene to capture Second Aeon in the 1970s. The big magazines of the 1980s included Ken Edwards’s Reality Studios, which I had written for and I had seen grow from a fascicle into a bound volume. I had no ambitions to take that route. I liked the SMALL in small presses, the LITTLE in little magazines. It was Ken who uttered the essential quote that I later used as a strapline to the first series: “a quick fix of the New British Poetry as it happens.” He caught the immediacy which seemed essential to me. This was a report from the writing desk, almost. The reference to the New British Poetry is a nod to the 1988 anthology The New British Poetry which Ken had helped edit. That was activity at the other end of the presentational spectrum: an anthology that would reach those beyond the small press network, those of us in the know, the elite, the outsiders, the dropouts of poetry, whichever way you look at it. For a heavily detailed account of this period in London — we were close enough in Surrey to feel that we still belonged to that scene — see my piece “The Colony at the Heart of the Empire” in When Bad Times Made for Good Poetry, which gives a sense of the multiplicity of activities going on in the alternative poetries of the time in London. It’s impossible to give a sense of that range, although perhaps it fair to say I saw most of the contributors to Pages reading at one time or another.

Frances: Thank you for your comments on the eviction collage and its context. I’m of that generation that expect our evictions to come arbitrarily from unscrupulous (are they ever much else?) private landlords, since as you say, the social housing has long since been sold off, and we have little expectation of buying. These are the conditions I write, read, and study under, so there is some comfort in the implicit solidarity of that gesture made some thirty years ago, which is, at a simple level, a kind of political gesture which acts other than programmatically, I think.

Your answers have been generous enough to anticipate some of what I might have asked about the kind of “scene” that Pages existed within or helped to constitute. Instead, I wonder about the selection process, and the poetics of Pages. In issue49–56 you enumerated what you perceived to be a number of common “operational axioms” for certain writers from the mid-’80s onwards and stated a need for debate and documentation around these emergent ideas. In issue 65–72 you hope that Pages will be a “variable forum” contributing towards “an active poetics to begin to help delineate a poetry that is ‘as yet largely unwritten,’ to encourage writers to take up its challenges, and to pay detailed attention to the little of its poetry that is already written.” I wonder about the relationship between this and the choice of poetry — was there any conscious effort to choose poetry that reflected a prior poetic ideal, or else to what degree did the poetics included follow as a consequence of the poetry, as well as the discussions of poetics contributed by others? In retrospect, do you feel Pages worked as the kind of testing ground it was intended to be, and how strongly do you feel the process of editing and encountering this work influenced your own developing poetics?

Sheppard: Looking back, the selection is quite eclectic, isn’t it? There are all sorts of poets there, and that’s its strength I feel, say Sheila E. Murphy, Kelvin Corcoran, and Harry Gilonis together in one issue. But at the same time, I was acutely aware that some of the poets around me, Gilbert Adair, Adrian Clarke, Ulli Freer, and others were straining for a new poetry and I tried to develop a poetics (what I would now regard as a speculative, writerly discourse rather than a manifesto) adequate to that work, work largely associated with the non-concrete poetry that was coming out of the Writers Forum workshop and developing at the SubVoicive reading series. I thought that the events at the Poetry Society in the 1970s had atomized a literary scene and it needed putting back on the right tracks. The arrogance or ignorance of youth! In 1988 Gilbert Adair coined that term “linguistically innovative poetry” — while adding “for which we haven’t yet a satisfactory name”! — which is now quite widely used as a synonym for avant-garde or experimental poetry — but we wanted to define it quite narrowly for a smaller group of writers who perhaps admired the procedures of Allen Fisher, a great influence and a Pages contributor, rather than say Eric Mottram, who seemed to be looking back to the New American Poetry rather than to the contemporary Language Poets, and still licking his wounds from the Poetry Society affair, or the Cambridge grouping which seemed too involved with the example of JH Prynne, great though he is. The result was less Pages the “quick fix” than the 1991 anthology I coedited with Adrian Clarke, Floating Capital: new poets from London. Notice this is all very London-centered activity, though the contributors to the magazine came from all round the country (Raworth and Ric Caddel for example) and abroad (Hanne Bramness; Creeley was a good catch, looking back!). The term “linguistically innovative poetry” was taken up at an academic conference in Southampton in 1994 by both Britons and US poets; again see When Bad Times Made for Good Poetry, where my talk “Beyond Anxiety” is reprinted. By the end of the conference everybody seemed to be using it. A result of a sort, I suppose … But to return to my original poetics statement in Pages, although this is the souped-up version from Floating Capital, this was my poetics (cum-manifesto) for myself, and I hoped, for others:

Poetry must extend the inherited paradigms of ‘poetry’; that this can be accomplished by delaying, or even attempting to eradicate, a reader’s process of naturalisation; that new forms of poetic artifice and formalist techniques should be used to defamiliarize the dominant reality principle in order to operate a critique of it; and that poetry can use indeterminacy and discontinuity to fragment and reconstitute text to make new connections so as to inaugurate fresh perceptions, not merely mime the disruption of capitalist production. The reader thus becomes an active co-producer of these writers’ texts, and subjectivity becomes a question of linguistic position, not of self-expression or narration. Reading this work can be an education of activated desire, not its neutralisation by means of a passive recognition.

It’s a mashup of Veronica Forrest-Thomson, Shklovsky, Adorno, Marcuse, Barthes, and others. In a lot of ways, I still believe some of these tenets, but I like to think today I can be multiform (as Pages was in fact) rather than near tub-thumpingly dogmatic in my commitment to unfinish. The term I used, “operational axioms,” to describe these points, is bullshit. Poetics has to be open to continual change. Of course, the poems from Fisher and Raworth that I published (from Gravity and Eternal Sections respectively) influenced me enormously. But then so might the Colin Simms or the John Seed — it’s difficult to say. But, as Adrian Clarke has recently noted so laconically, in a piece for Robert Hampson, about the 1980s in general, and about wordcount metrics in particular: “Late C20 London Neo-Formalism has possibly failed to take its rightful place in literary history so far through its participants’ temperamental disinclination — we did not number an André Breton in our modest ranks.” It creased me up when I read that!

Frances: As you say — I think the selection of work in Pages was rather eclectic, and if the tone of some of your editorial pieces is ever a little strident, it seems to me that’s directed out to a more mainstream poetic culture which barely noticed poetry of the kind you were publishing. But that’s an old story, my point is that I think the eclecticism of the poetry and poetics in Pages does suggest a somewhat multiform approach to these questions of developing poetics. It was certainly a pleasure to read through all that variety as I was copying them. Anyway, I think that about covers my major bases. People may be interested, from a historical point of view, in the kind of numbers of copies were being sent out each month — and, besides that, if there’s anything else you’d like noted on the magazine for posterity, any other stories you’d like told before we tie up?

Sheppard: Numbers: it never exceeded one hundred, I know that. It was a cottage industry, and I do remember that I didn’t manage to keep up the promise of monthly publication. It is a shock to realize that I had to send back poems by the underrated Asa Benveniste and some excellent short lyrics by John James. But I did manage, of course, to do a second series, under the strapline “resources for the linguistically innovative poetries,” but it was less ziney, even in size: A4 pages featuring one poet per issue, with poems, poetics, a critical article, and a bibliography. Getting articles written by others for no reward was a slow process, and I’m glad I didn’t attempt regular publication. I selected twelve poets, so I wonder whether I conceived of this as monthly over a year. The poets were: Alan Halsey, Ulli Freer, John Wilkinson, Adrian Clarke, cris cheek, Rod Mengham, Virginia Firnberg, Ken Edwards, Peter Middleton, Hazel Smith and — the last to get done, bringing the page count to 445, and dated 1998 — Maggie O’Sullivan. By that time, we were in Liverpool. A third series was attempted in 2005 on my blogzine Pages, but it petered out, or rather, it transformed into a literary blog, which is still going today. So, in one sense, Pages never finished.

Reissues commentary