'or we could simply talk about poetry!'

The pioneering digital poetics of Loss Pequeño Glazier

Thus the poet knows which lines the poem could contain but never which lines the poem will contain, these decisions made by the algorithm’s desultory logic. The output is clearly seeded by the poet, each permutation the product of human deliberation, linguistic invention, craft, play, and articulation of the poet’s vision — but the generation of a stanza occurs only at the precise moment of reading. A study in poiesis! — Luna Lunera, Loss Glazier

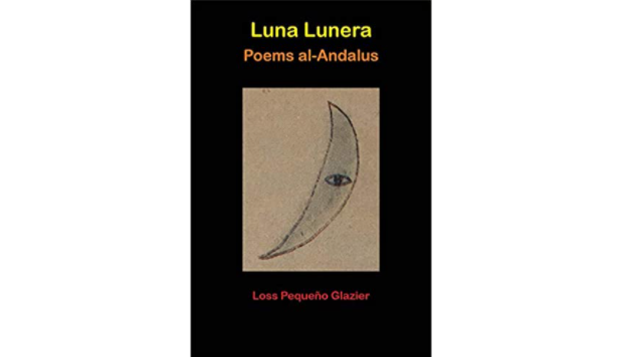

For poet, digital artist, and scholar of e-literature Loss Pequeño Glazier, the intersection of the two — algorithms and poetry — has always intersected. He has done this pioneering work in the inception of the field as a graduate student and professor at SUNY Buffalo, and his book Digital Poetics: the Making of E-Poetries is one of the foundations in the field as the first book-length study of digital poetry published in 2002. His other publications include Anatman, Pumpkin Seed, Algorithm (Salt, 2003); the digital works, white faced bromeliads on 20 hectares (1999, 2012), Io Sono at Swoons (2002, 2020), and Territorio Libre (2003–2010), all featured in digital poetry performance film, Middle Orange | Media Naranja (Buffalo, 2010); and now new book Luna Lunera: Poems al-Andalus (Night Horn Books, 2020).

His most recent book, Luna Lunera: Poems al-Andalus (Night Horn Books, 2020), is a ten-year project culminating in a collection of print poetry drawn from print poetry, digital poetry, and dance performance scores, code, and digital processes. Luna Lunera, the culmination of these language-media works, now appears in print form — the output of multifaceted, cross-media renderings that find expression in the print iteration. Luna Lunera is supplemented on the web with digital poems, solo readings (video), dance performances (video), and supplementary documentation.

SUNY Buffalo’s Department of Media Study, where I currently work, is a place where pioneering figures in media arts taught, including Tony Conrad in composition and video, Hollis Frampton in experimental film, and Loss Glazier in his pioneering work in digital poetics. Currently, Loss Glazier is professor emeritus of media study at SUNY Buffalo, New York; director at the Electronic Poetry Center (now hosted by the Kelly Writers House, University of Pennsylvania); and director of the E-Poetry Festivals. He has also served as artistic director of the annual Digital Poetry & Dance performance (University at Buffalo). He has been called “distinguished writer of electronic poetry” by N. Katherine Hayles. He now lives and writes in the Smoky Mountains.

What follows is a dialogue of exchange, of poetry, and information from Loss in an experimental interview text that sheds light on automated poetics.

The digital is literary

Code is poetic

bpNichol and a legacy

Messy your hands in code to reach

Into the inner poetics

Of digital poetry

Your work in digital poetics has been an intervention and pioneering in the field. Can you describe further your approach to digital poetics, and especially when creating and contributing to the field of electronic literature?

My work centers around the fact that I have always seen digital literature as literary. Few literary people seem interested in cracking open the code and climbing inside. Very few digital practitioners, even now, approach the field from a literary standpoint, most having technical and/or theoretical expertise but no poetic engagement. There are very few poets and almost no other poet-programmers working in digital poetics as a literary space, really since bpNichol (1983).

To me, you have to have your hands in code to enter the inner poetics of the digital poetry medium.

I also think it’s important for an artist to contribute to the community: create gatherings, publish others, etc. Not to expect to receive adulation solely on the basis of their work.

After years of interest in small press, the Mimeo Revolution, descriptive bibliography, and text analysis software, I began in digital poetics when I founded the Electronic Poetry Center (EPC) at SUNY Buffalo. I have directed the EPC since its founding in 1994, a site that predates the web. At the time the web went live, the EPC was the first digital literary site anywhere and may very well still be the largest in sheer resources.

You began researching digital poetics in the 1990s when the internet was being developed. How did you first get interested or see this intersection of poetry/digitality? Given you were at SUNY Buffalo, and the experimental poetry movement with Charles Bernstein, how significant were those collaborations and conversations?

My entry into digital poetics really began with the “Osborne 1” computer in 1981. When I saw how you could change text in memory and output your work instead of backspacing with the erase key on the Selectric typewriter, I was all in! (Though the Selectric’s font elements were really tactile.) This interest was developed through investigations of the Mimeo Revolution, compilable PL/1 and Java, and JavaScript. My research came from practical, theoretical, and hands-on experiences. It was clear to me that code was a form of writing-within-writing. Even to be able to do a little bit of coding opened paths to understanding the medium that third-party computer interfaces were designed to conceal. When I explained the technology to Bernstein in the ’90s, he was very supportive, regularly funding the EPC and providing exposure through his many activities. There was good collaboration between the EPC and the Gray Chair in those days. Keep in mind that the experimental arts/media scene had been stellar for a half century at Buffalo: in poetry with the UB Libraries Poetry Collection; in English with Al Cook, Charles Olson, and Creeley; in music with Morton Feldman and John Cage’s influence; and in media study, especially its legendary era with media makers James Blue, Tony Conrad, Hollis Frampton, Gerald O’Grady, Paul Sharits, Steina and Woody Vasulka, and Peter Weibel (all “digital poets” in a metaphoric sense); and in the Poetics Program with Bernstein, Susan Howe, Federman, and Dennis Tedlock. Buffalo was primed for the latest form of language/media/sound experimentation — and for the digital poetry to be born and put on the Web at the EPC.

How significant was SUNY Buffalo in the development of EPC and digital literature?

The EPC has benefited enormously from being at Buffalo. Robert Creeley was delighted with the possibilities of digital space, and Charles Bernstein, who subsequently held the Gray Chair, was always greatly supportive of our efforts. (Both also embarked on their own related projects. Bernstein continues to contribute to the EPC to this day.) The UB Department of Media Study (with the vision of Roy Roussel and the magnificent energy of Tony Conrad) provided a home base for the EPC and its satellite projects to fully culminate. (Media Study also provided infrastructure for the Digital Media Poetics series I curated from 2002–2017.)

Can you share more on how you developed your key ideas in Digital Poetics: the Making of E-Poetries?

Key ideas really came from building the Electronic Poetry Center itself (structured according to library organization and archival standards), immersion in Poetics Program readings, and in setting out across the world to participate in numerous digital gatherings. Digital literary art offered a kind of lingua franca across cultures, similar to how music can appeal across international lines. One doesn’t always know the words, but the structures, the images, the sounds cross many boundaries. It was happening in various countries at once.

How do you see code and writing code as poetic, and how are words like code?

Code is poetic because “poiesis” literally means the art of “making.” This occurs in all media, including how potters position their hands when at the wheel or when a weaver uses repetition and variation to create their works. Literary code makes literary works. It is “writing” because not only does the code use semantics and syntax to make meaning on the code level but this code level is the structure [that] structures text in online space — a kind of 3-D chess effect. The poet-coder can see how poetic language displays on the screen and move around its underlying code to watch the nuances of the code-language interplay shift subtly on the screen.

Your artistic interests moved into dance, can you share more on why and how dance and e-literature came into conversation?

Given the disembodied, “virtual” nature of digital writing, I took time to concentrate on its physical manifestations. Since dancers express themselves artistically through their bodies, it was very interesting to see how they would interpret digital literature. To perform my texts onstage as they danced also opened doors to vocal performance as the physical embodiment of my work. One of poetry’s many faces is in performance. Working with dancers allowed me to experience whole new approaches to performance — and there is nothing like professional-level black-box-theatre dance performance to immerse one into a swirl of creative energies! All this makes your work on the page and onscreen so much richer. It is also a true learning experience to reach across disciplines.

What is array poetics, and how does it inform your current work Luna Lunera?

Array poetics is a specific mechanism in coded poetry that allows the author to define a region and then, instead of putting one phrase in that region, ask an algorithm to select from a range of variant phrases. If the array exists at the end of a line, for example, this allows you to tell the machine to select from a set of specific, author-produced choices to end that line but to vary which individual variant it puts in at a given moment. Thus, the author knows what might appear but never what will appear at any given time. This opens up a whole new world of compositional invention. It really energizes your relation to language! (Plus, you are never limited to just one lexical choice, allowing you to stretch and bend your creative expression in ways that fixed text does not allow.) As a poet, after I watch literally thousands of unpredictable variations in a text I created, a deeper knowledge of the work is acquired. One now sees inside the poem or has some sense of inner dynamics underlying the interactivity of the words, how they slip, how they rub together. Luna Lunera takes that inner knowledge and builds back out again to create a print book — not just a composed text but a poem enriched by having seen their variants in a multitude of variations, settings, and across media, producing the finished articulation: a book.

Please share more on [how] the concepts and inspirations of Luna Lunera can successfully cross over from the world of its themes (Lascaux caves, Edinburgh Castle, Robin Blaser’s “The Moth Poem,” Andalusia) to a tapestry of language textures, made vivid by digital engagement, language play, visuality, “book-ness,” and dance choreography.

In terms of the thematic sections of Luna Lunera, just as a stage is a setting for dance, they have settings — as you mentioned — in “real” (or imaginary) worlds. In each of these settings [documented in “Scenes”], there are different locations, conversations, or histories that the poems take up. At the same time, the digital process engages the textures of the language of these settings and weaves them into an aesthetic response shown through in the author-created interface of the digital versions of the poems [also accessible on the site]. Luna Lunera, as a book, is a reading of the “complete” poem — the versions, the variants, the performances, the choreography (videos also available on the webpage), the interfaces, the arrays, the code — as a single, author-produced text. After so much digital, physical, and creative activity, a book comes into being — poetics!

Currently, I’m focusing on diversity and inclusion with the Electronic Literature Organization, and as you have pioneered in the field, I wondered if you had any recommendations on how the field and the organization could be more diverse?

That’s a little difficult because outside of the main repositories of wealth in the world — the US/Canada, Europe, Australia — many of the world’s people are still working on basic economic needs, so it may be that we have more access to digital artistic expression. In this country, specifically, I think you need to look hard at what’s been done by persons of diversity — there are many — and they mostly go unheralded. They have not, for the most part, received awards. Further, if any new awards are created, it’s tricky ground. I think it’s important to make them at the level of mainstream awards, being wary of marginalizing them accidentally as, for example, “best Latino work,” or “best work with Spanish content.” (Though, of course, those awards have great value in inspiring others!) Yet, a Latino should be able to win “best work” on equal terms. It’s hard to go against systemic inequities. I know. I would further suggest that awards require literary merit clearly separate from administrators, figureheads, or academics. It may take thinking broadly about the “digital” and “literary” to accomplish this. There must be artistic merit for this all to matter! I appreciate the question. I am grateful for your attention to this important area.

Loss Pequeño Glazier

N.B. All works available here. “Early Visual Works” (Viz Études, On Your Marx, Cordoniz) are under “Libros de Papyrokinesis”; “Media Naranja” (Bromeliads-Io Sono-Territorio triad) are under “L’êtres: E-Poésies Fondamentales”; “The Cuchufleta” works are represented by “cuchutexto” (one section of them); and Luna Lunera (“Etymon,” “Guillemets,” “not-moth,” and “Mudéjar, Alcazar”) appears per se, with additional material (esp. “Scenes”) on its own page.

Automated Poetics