Baking with Emily Dickinson

An interview with Houghton librarians Christine Jacobson and Emily Walhout on your virtual birthday party

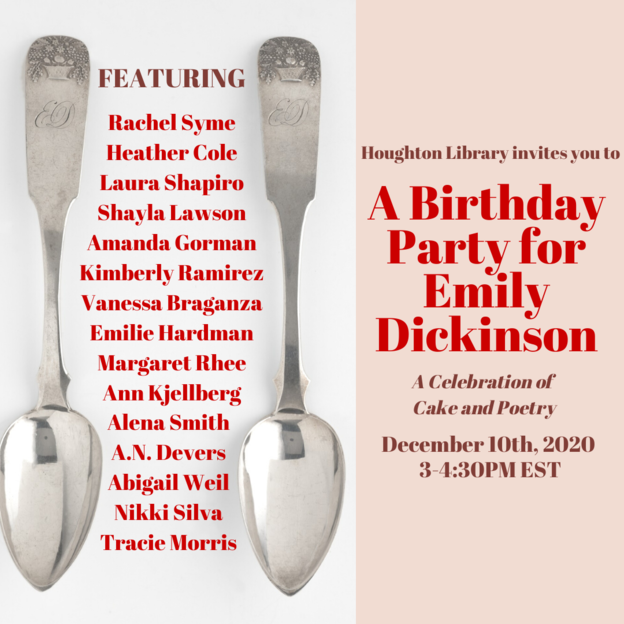

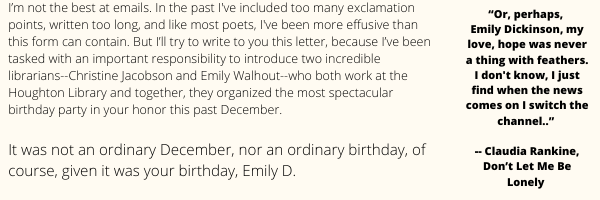

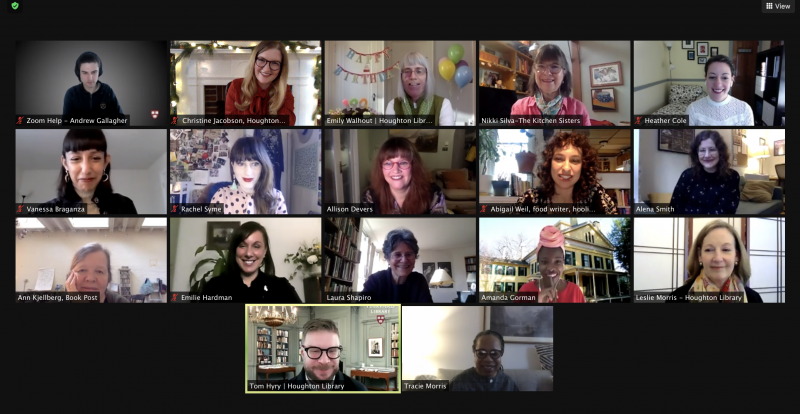

Libarians Christine Jacobson and Emily Walhout introduction (courtesy of the Houghton Library).

Libarians Christine Jacobson and Emily Walhout introduction (courtesy of the Houghton Library).

Some more details: we met via Zoom (not an ordinary December, because we were in a pandemic) and Emily and Christine curated a spectacular list of readers. From poets, television show runners, journalists, food writers, scholars, and numerous individuals from all walks of life, arts, and culture — more than 667 people — to celebrate you.

Group photo of Zoom event (courtesy of the Houghton Library).

Group photo of Zoom event (courtesy of the Houghton Library).

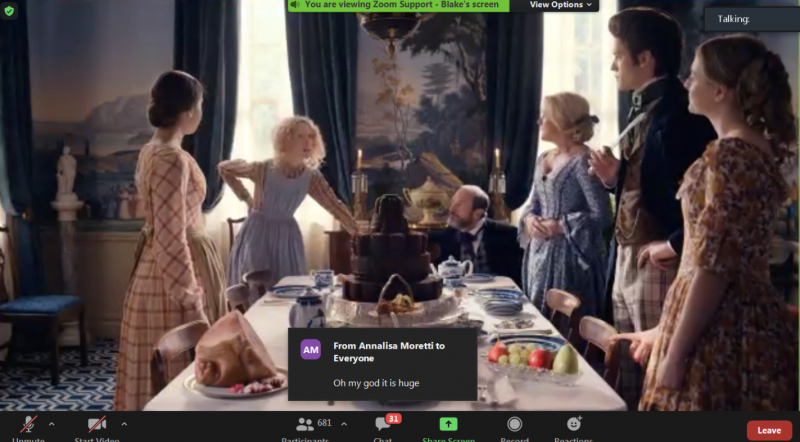

Some of the readers included the poet and performer Tracie Morris, the television showrunner and creator of Apple TV’s Dickinson, Alena Smith, NPR’s Nikki Silva, cocreator of “The Kitchen Sisters,” Rachel Syme of the New Yorker, poet and Shayla Lawson, the young poet and model Amanda Gorman, and more exciting artists and writers. We were able to watch a preview of Dickinson with Alena’s reading. The event was held in December, just before the new year. In a challenging year. By early spring, a few short months later, Amanda would give the most compelling poetry reading for the Presidential inauguration, when our nation finally voted for change. It was so special to hear Amanda speak at your birthday party on how much your poetry meant to her. In addition to Amanda I place the full list of readers below this letter, and how special it was to beside such illuminaries to celebrate you, and black cake.

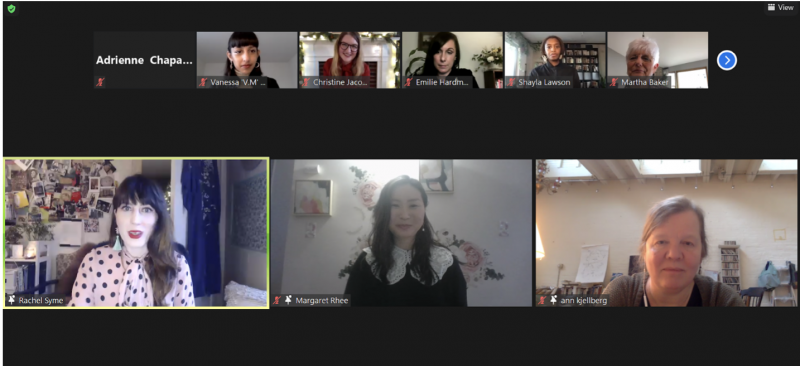

(Courtesy of the Houghton Library.)

(Courtesy of the Houghton Library.)

Because, for this birthday Zoom event, we baked together, ate together, read together, and shared words of yours. Oh, the pleasure. Oh, the love. Somehow you always seem to bring people together, another kind of hope with feathers.

Photo of Dickinson still (courtesy of the Houghton Library).

I wanted to learn more about how Christine and Emily organized such a special event for you and us, and given the ephemerality of Zoom or any reading events, and the eating of cake, I thought it’d be nice to hold space for and archive what occurred. The specialness of celebrating you. The poetry. The community. Light. For when I responded to the invitation by Christine and Emily, I wrote something like, “this event is a kind of salve,” and really it was. I didn’t use numerous exclamation points. I just used that word. Salve.

Emily Walhout (going forward will be called Emily), with other librarians at the Houghton, we’ll learn more later, started baking your black cake in 2015, and it became a tradition.

I should mention that Emily is, alongside a librarian, a professional viola da gamba and baroque cello player of music from 1500–1750. Christine is also a librarian at the Houghton Library, and has expertise in underground Soviet Union and writers and poets. Together, this year they made the perfect pair to create a stunning intergenerational and diverse group of women writers all engaged in your work. (They invited one male poet who could not attend.) Perhaps all for the better, maybe. :)

In the interview below we learn more about how Emily, alongside colleagues such as Emilie Hardman and Heather Cole, helped start the tradition of baking your black cake. With the recent virtual bake and Zoom event Christine and Emily created, with even more people engaging in the tradition, over hundreds internationally, the poetic and baking ritual has grown.

Just a year before the event, I met Christine in Cambridge when I was teaching at Harvard on fellowship. My poetry seminar was lucky enough to make a visit to the Houghton with a special guest talk by Christine on your work and a visit to where your books and chairs were held. Christine did a riveting job in her talk to make your work come alive. I’m grateful for her teaching and curating. How extraordinary to have the students, all inspiring, emerging writers and poets and artists, to learn about you hands-on. This is what the archive can do. Here, I first saw how you brought people together. I met Christine because of you. The students met one another, and remet you that day — anew.

In the interview, Emily mentions how you lowered the wooden pail to the children of your neighborhood in Amherst to share your baked goods, and I think about the pleasures of baking, and writing poetry. More than a recipe, baking itself includes ingredients, when placed in order and together, make something wholly new, satisfying, typically sweet, and that brings smiles to faces. You wrote poems and letters, and we must know you used your hands to do something else. Baking for one — mixing, measuring, licking — and perhaps the other with something else more akin to loving and being loved. As Martha Nell Smith writes, “as Paul Valery suggested, ‘a poem, like a piece of music, offers merely a text, which strictly speaking, is only a kind of recipe.’”

The morsel, like the poem that’s read, a poem that’s recited aloud, is heard, then gone. It makes sense, Emily the Baker, Emily the Poet, Emily my love, you do bring us hope.

Here are some photos of the poems the students wrote in response to your archival materials, photographed and posted on the chalkboard. Scrawls of chalk as a response. For this day, I also baked black cake for the first time, my first time baking really. I baked cake for the first time because of you.

Like a perfect black cake, with chosen company, Emily and Christine made something that was not possible in the pandemic. They brought us you, and brought us together because of you. Like a recipe for cake, we came together for something special. And so I write this letter as an introduction to Emily and Christine, because it was in the letter you wrote to Nellie Sweetser that you included your recipe of black cake years ago that still touches us today.

Emily Dickinson place setting from Judy Chicago’s “The Dinner Party,” 1974–1979, Brooklyn Museum. Photo by Philipp Messner, CC BY-NC 2.0.

It felt as if artist Judy Chicago’s “The Dinner Party” came to life. Judy’s installation is a massive and gorgeous funky feminist banquet on a triangular table of thirty-nine settings for important women in history. This piece is iconic within feminist art, and I enjoyed viewing it two years ago at the Brooklyn Museum. The table settings are “china-painted porcelain plates with raised central motifs that are based on vulvar and butterfly forms and rendered in styles appropriate to the individual women being honored.” When I saw the real thing in Brooklyn, it was your place setting I stayed and lingered a bit longer for. It’s written in the Brooklyn Art Museum that you were reclusive, perhaps following many portrayals and writings about you. But we know from scholars such as Martha Nell Smith, Cris Miller, the film Wild Nights by Madeleine Olnek, and Alena’s Dickinson on Apple TV that you were not.

You were a lover, a sister, a baker, and a poet, and more.

In Chicago’s installation, the plate with your name sits atop a mid-nineteenth-century collar of porcelain, frilly lace, ribbon work done in the 1800s. Vibrant, pink, and flowing. All together now. And that’s how the event felt. Like you came to life at “The Dinner Party,” and there we were, able to break cake with you.

I think you would’ve enjoyed as much as we did what Emily and Christine did for your birthday. We had a party. Together.

Gathering people together is an art. A poetic act that continues to extend. I savor these sweet connections and the women and others who make this space happen. It’s you.

With love,

Margaret

__

This is my letter to the World

That never wrote to Me—

The simple News that Nature told—

With tender Majesty

Her Message is committed

To Hands I cannot see—

For love of Her—Sweet—countrymen—

Judge tenderly—of Me

(Dickinson, Complete Poems, 211)

List of Party Readers

__

Allison Devers, proprietor of the Second Shelf

Shayla Lawson, poet, author, and professor at Amherst College

Alena Smith, creator of Apple TV’s Dickinson

Rachel Syme, staff writer at the New Yorker

Nikki Silva, NPR, the Kitchen Sisters

Laura Shapiro, food writer, author of What She Ate

Tracie Morris, scholar, poet, author, and former Woodberry Poetry Room Creative Fellow

Ann Kjellberg, editor and founder of Book Post

Heather Cole, librarian for Literary and Popular Culture collections at Brown University

Margaret Rhee, poet, new media artist, and assistant professor in media studies at SUNY Buffalo

Emilie Hardman, Head of Archives and Digital Strategy at the Center for Creative Photography

Amanda Gorman, poet and 2017 National Youth Poet Laureate

__

Interview with Christine Jacobson and Emily Walhout

The celebration of Emily Dickinson’s birthday with the baking of black cake is a special Houghton tradition that transforms the archive recipe to actual baking and celebration in person. Can you share how the event began? Who is Team Cake and how does it illuminate Dickinson’s baking, and how has it evolved?

Emily Walhout: First off, you should know that the Emily Dickinson Collection at Houghton Library is the largest collection of the poet’s manuscripts in the world; along with the Dickinson family library and many household artifacts, it preserves more than one thousand autographed poems and some three hundred letters. It is in one of these letters to Nellie Sweetser in the summer of 1883 that Emily tucked in her recipe for black cake. As a seasoned reference assistant in the Public Services department, I’d known about this recipe for some time, and it always surprised me that no one at Houghton had tried it out. It seemed obvious that we needed to do this. But it was not until Emilie Hardman joined our ranks that the wheels started to turn. You see, Emilie is a consummate baker (she even had a business on the side creating vegan wedding cakes), so I’d finally found a willing, and more importantly, capable accomplice. Thus, Team Cake officially launched in the fall of 2015. We two Emilies were joined by Heather Cole, then-assistant curator of Modern Books and Manuscripts, who was forgiven for not being named Emily too.

The idea was to try the recipe, all twenty pounds of it, and serve the cake to our fellow Harvard librarians at a birthday party for the poet in December. Born on December 10, 1830, Emily would have been 185 at our first party. Black cake is a fruitcake, so it is best baked well in advance so it can mature, steeped in brandy, for a couple months before serving. We were committed to sticking to the original manuscript, its ingredients, and instructions (precious few) as strictly as possible, so as to experience as closely as possible what the poet herself may have experienced and to see what we could learn. We discovered that the whole process produced more questions than answers. We pondered or agonized about nearly every ingredient and wondered about or marveled at each process, but three questions that were foremost in our minds were: 1) What is citron, and did she candy it herself or purchase it? 2) Did she use salt? (The recipe does not call for it.) and, 3) Did she have really toned arm muscles from stirring twenty pounds of cake batter?!

I invite you to read our two blog posts that delve more deeply into our process, our questions, and our discoveries about Emily the poet and Emily the baker, black cake, and baking from the archive. Each post includes a delightful video so you can watch along as we bake Emily’s cake:

Baking Emily Dickinson’s black cake from our first celebration on December 11, 2015

and

Emily Dickinson’s Birthday Party: Cake, Hope, and Camaraderie from our party on December 9, 2016.

We’ve continued baking the black cake in September and serving it in December every year since then. Team Cake has a loose and ever-evolving, ever-widening membership, or perhaps fellowship may be a better word. Various friends and colleagues (even a mom once) join in the baking every year. Heather Cole moved on to Brown University, and her successor in Modern Books and Manuscripts, Christine Jacobson, joined in 2018. Emilie Hardman also moved on, first to MIT and now she’s at the Center for Creative Photography in Tucson. But once a member, always a member, at least in spirit. And now given the enormous success of our 2020 virtual bake and Zoom celebration, I think we’ve added hundreds across the globe.

Due to the pandemic, the reading celebration and baking this year were virtual, and you both did an incredible job of curating a diverse and intergenerational and interdisciplinary — from the Kitchen Sisters, Alena Smith of Dickinson, to Amanda Gorman before the inauguration! — event of women. It seemed really in the spirit of Dickinson, and could you both share on the process of curating the event, and what elements were important, and how it was different and made possible of holding it virtually versus in person?

Christine Jacobson: While we mourned the interruption of this beloved tradition, moving the baking and birthday celebration to the virtual world presented some really special opportunities. Since we couldn’t bake for our friends and colleagues, we decided that it was important to create a community of bakers by inviting the rest of the world to bake with us from their own kitchens, and encouraging them to share pictures of their bakes online using the hashtag #BakingWithEmilyD. To get the word out, we collaborated on a blog post that explained the tradition.

Crucially, Emily W. devised a reduced recipe that would make one loaf instead of the twenty pounds of cake Emily’s recipe produces so we wouldn’t scare anyone away! Since the cake needs time to steep in brandy before serving, we encouraged bakers to make the cake in the autumn and bring a slice with them to the birthday party in December. It was so cheering to see everyone’s bakes online. You can still see many of those posts here.

When we thought about who we wanted to invite to read at the virtual birthday, we thought about the tapestry of women we know to be part of the Emily Dickinson community — poets and food writers, librarians and booksellers, television creators and radio producers, scholars and educators. The readers were all women Emily and I had come to know in the course of our day-to-day work, which is actually really humbling to think about. I wouldn’t say we necessarily set out to exclusively invite women to participate (in fact, we invited one famous male poet who declined our offer due to a schedule conflict) but once the lineup was in place, it felt right.

Baked goods are ephemeral, and yet Emily Dickinson wrote poems and baked too. It seems baking was a way Emily Dickinson shared baked goods with the neighborhood and reflected on community building. I wondered if you both can reflect on how baking and poetry, or recipes and poetry intersected in Emily’s work/worlds? How does the baking of black cake today extend her legacy or poetic practices?

Jacobson: In her wonderful book, What She Ate, food writer Laura Shapiro writes, “while extraordinary circumstances produce extraordinary women, food makes them recognizable.” When I am asked to teach classes on larger-than-life figures in Houghton’s collections, my challenge is to make someone like Emily Dickinson seem real, rather than an abstract fact, e.g. “Emily Dickinson (b. 1830 d. 1886) is widely regarded as one of the most important figures in American poetry and lived in Amherst, Massachusetts.” While Houghton is lucky to have poems written in Emily’s hand, I think her recipe for black cake helps people connect with her. A recipe exchanged between family members or friends is an intimate gesture of generosity. Even if you’ve never tried your hand at making a fruitcake, you’ve probably made something, saved a recipe, or brought treats to a friend in need. Food is a universal language!

I don’t feel equipped to weigh in on the connection between baking and Dickinson’s poetic practices, so I’ll instead recommend an essay by M. NourbeSe Philip called “Making Black Cake in Combustible Spaces,” which explores Philip’s relationship to black cake as a Caribbean dish, her attempts to describe it using the Caribbean demotic, and the combustible space of Dickinson’s kitchen as a site of consumption where the poet absorbed both ingredients and vernaculars that were not her own, but are reproduced in her black cake and in her poetry. It’s a stunning essay.

Walhout: Aife Murray is someone else whose work investigates Emily’s relationships with her servants. In her book Maid as Muse: How Servants Changed Emily Dickinson’s Life and Language, her blog Maid as Muse, and her multiform project Kitchen Table Poetics, Murray explores the intersections of class, race, and artistic reciprocities in the Dickinson household.

Any other insights you’d like to share from the process of making black cake or the recipes?

Walhout: If you search “Dickinson black cake” on the Internet, you will come up with a host of blogs and videos of other people baking this cake too. People know about it and want to try it, to establish some sort of material connection with one of America’s (perhaps even the world’s) best-loved poets. But if you follow closely, you will see that most others will change up the recipe. I guess that’s to make it more tasty to the modern palate? Do they not trust a nineteenth-century recipe, relatively low in number of ingredients, and certainly low on instructions? When I see all the present-day changes made to the Emily Dickinson recipe, I wonder, “Why mess with an already perfect cake? Especially even before you’ve tried it!” What’s more, if you change the recipe, can you still call it Emily Dickinson’s cake?

And that gets me thinking about origins. Is it really Emily Dickinson’s cake in the first place? Some may know that black cake, or rum cake, is a Christmas season tradition in the Caribbean. Food historians tell us that black cake’s ancestor was probably the British plum pudding, which was brought to the Caribbean by the British, possibly by missionaries, but most certainly also as a result of the sugar and slave trade. The people of the Caribbean took that pudding, substituted local ingredients, notably rum instead of brandy, and dark molasses or burnt sugar syrup, to modify the British pudding to make it their own. This new world cake is much darker, almost black, and richer in flavor. Throughout the Caribbean it is traditional to honor your close friends and relatives with a special gift of black rum cake at holiday time.

Emily’s recipe calls for brandy, the British ingredients, as opposed to rum from the Caribbean. But it also calls for a substantial dose of molasses. So it’s a hybrid — with elements of both old- and new-world cultures. We’ve always used white sugar, but did Emily mean white or could she just have easily used brown? Would historically informed baking allow for brown sugar? The whole process continues to generate questions, as it did in 2015 when we made Cake #1, but isn’t that often the case, perhaps even the point, with archival and historical study?

You’re both librarians at the Houghton, and with expertise not only on Emily Dickinson but also in Russian literature and poetry (Christine), and cello and viola da gamba music (Emily). Would you like to share more on these interests and how they intersect or inform your approach to Dickinson’s archives and celebrating/engaging with her work today?

Jacobson: A phenomenon I’m fascinated by is self-publishing. Writers and poets living in the Soviet Union evaded censorship by producing and circulating their works underground in a format known as “samizdat” (“sam” = self; “izdat” = to publish). Some of the greatest works of Russian literature were first published as samizdat — Bulgakov’s Master and Margarita, Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago, and Akhmatova’s Requiem. Of course, this tradition of expression has surfaced in many places and periods — Black and Indigenous writers in nineteenth-century America self-published pamphlets and narratives to avoid edits by white commercial publishers; LGBTQ, feminist, and fanfic communities forged zine communities throughout the twentieth century; and today platforms like Medium and Tumblr give everyone the power to find their voice and audience. I think it’s interesting and instructive to think about Emily’s fascicles — the bundles of fair copy poems found in her bureau after her death — through this lens. Like the groups mentioned here, Emily’s relationship to publishing was fraught. (NB: Alena Smith’s exploration of this in season 2 of Apple TV+’s Dickinson is spectacular.) However, it’s not clear that Emily sewed her fascicles to find community or audience; but rather, that she found meaning and purpose in the process of their production. (This is not an original idea: several scholars have written compellingly about Emily’s fascicles as a form of publication, including Eleanor Heginbotham and Cristanne Miller, among others.) I believe contrasting Emily’s practice with modes of self-publishing helps students encountering her work for the first time connect with the curious poetry bundles, and raises for them interesting questions about what it means to produce works of art without an audience.

Walhout: In my life outside of Houghton Library I am a professional viola da gamba and baroque cello player, specializing in Renaissance and Baroque music roughly between 1500 and 1750. This field of early music, sometimes called historically informed performance, is founded on endeavors to discover and replicate to the best of our abilities what composers may have intended, how performers may have played, and what listeners may have heard hundreds of years ago. I think of our black cake endeavors as historically informed baking. When Team Cake sets out to make this massive cake we ask the same questions early musicians ask: “What would we, could we, learn about our forebears and their experiences, their tastes, their creations and their world, by sticking to the recipe as faithfully as we are able? What would we find out? And what in turn would this teach us about ourselves?” These questions are at the heart of archival research. Asking them about recipes in archives is even more fun because food is involved! And along with food comes tradition, generosity, and camaraderie. I think of Emily Dickinson lowering cakes in a basket from her second-floor window to eager children below. I think of her enclosing a little gift of a recipe in a letter to a friend. Food brings people together over time and space. That’s something we desperately need in these times. I love seeing people’s eyes light up and their hearts open when they sample a piece of black cake, view the original recipe written in the poet’s handwriting, and get curious about Emily Dickinson the person, the baker, the poet. It’s a great way to introduce people to Houghton’s Dickinson collection and archives in general. Everyone can relate to food, right? So it’s an easy entry into a place that may seem intimidating otherwise.

Our black cake bake is actually only one in a series of recipe reenactments at Houghton that we call “Cakes from the Collections.” Mary Hyde Eccles was a major donor of eighteenth-century Johnsonian materials to Houghton, and in honor of her birthday in 2016, we baked Eccles cakes from her own handwritten recipe. And just before the pandemic hit we hosted a Valentine’s Day dessert party for our Widener Library colleagues that featured at least fifteen different historical cake and pie recipes from our collections.

What are your favorite Dickinson poems and baked goods?

Jacobson: My favorite Emily Dickinson poem is “We talked as Girls do — .” I love the conspiratorial, subversive vibe of it, as well as the sanctity with which Emily imbues late-night conversations between women.

I was born and raised in Florida, so my favorite desert is key lime pie. (Houghton boasts a literary connection to this treat as well — we have a recipe for key lime pie sent from Elizabeth Bishop to Frank Bidart from 1974.)

Walhout: I’ve got a number that vie for that top position, but if I had to choose my absolute favorite it would probably be “I’m Ceded — I’ve stopped being Their’s.” This one resonates so deeply with me because it so aptly describes my stance toward my own doctrinaire Calvinist upbringing that whenever I read it I wonder in amazement, “Dear Emily, how could you know me so well?” There’s such power and purpose there as Emily writes of her need and intense resolve to grow into and choose her full, authentic self over what others expect of her. For me it is quintessential Dickinson.

A close second is “It might be lonelier.” As a bit of a recluse myself, I sometimes think I might be a bit too attached and accustomed to isolation. (Hate to admit it, but I was pretty much in my element during the pandemic.) Overcoming aloneness and any suffering that comes with it can be daunting work, while taking on a more positive outlook can feel like a bit of a betrayal. Wouldn’t I miss my old lonely self? And despite the fact that I can imagine paths out, indeed, it feels easier, more comfortable, more comforting not to try. But oh, Emily’s alternative is so ecstatic! That image of the Blue Peninsula, appearing so unexpectedly at the end, kills me every time. The relief and sheer blue beauty of it. And I love the double meaning of “to perish of Delight.” She recognizes the ecstasy that awaits, but will she dare reach out to grasp it? If she does, she risks the loss of her familiar lonely self, but she gains a rapturous Delight that is to die for. It’s a tough decision, an inner battle, that I can relate to.

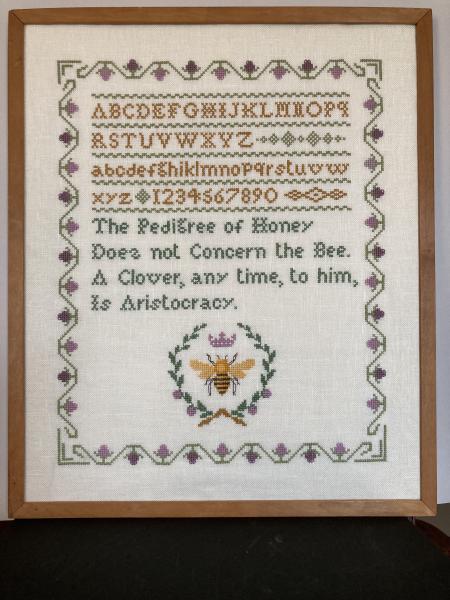

And then I do really like the petite

The Pedigree of Honey

Does not concern the Bee—

A Clover, any time, to him,

Is Aristocracy—

I love the egalitarian sentiment. I even made a cross-stitch sampler of it, inspired by the sampler stitched by Emily’s mother that we have at Houghton Library.

(Needlepoint by Emily Walhout, courtesy of Emily Walhout.)

Favorite baked good? Cake has got to be my favorite. I’ll take most any kind, but I must say that I am delighted when December comes along and I get to have black cake again. The spices are extraordinarily tasty, and they linger on the tongue in such an intoxicating way. (Or maybe that’s the brandy.) Granted, there’s no one stopping me from making black cake all year round, but the tradition has become a cherished one to look forward to as winter sets in.

What are your next projects?

Jacobson: As an enormous fan of Apple TV+’s Dickinson, I’m working on bringing creator and producer Alena Smith to the library to discuss the research and design process of the show. We’re in the early stages of planning this event, so watch Houghton Library’s website for more details. I’m also excited for Houghton to launch this fall its website on “Slavery, Abolition, Emancipation, and Freedom,” a project I’ve been working on led by our colleague, the Digital Collections manager Dorothy Berry. The website will bring together over two thousand digitized letters, manuscripts, publications, pamphlets, and ephemera that document the Black American experience from the founding of the Republic through Reconstruction. But frankly, reopening the library to the public after the pandemic, and meeting the immediate needs of students, faculty, and researchers is our collective “project” at the moment!

Walhout: It’s time to start thinking about our seventh annual Dickinson birthday celebration. September, cake-baking time, is right around the corner. Due to the continuing uncertainties of COVID, we’re not certain what form the celebration will take this year. Will we be able to serve cake and coffee at an in-person gathering in December? We’ll have to see. In any case, Team Cake will bake again this fall, and then we’ll figure out what to do with four 9 x 13 pans-worth of rich, raisiny Delight.

Attendees at the 2020 Zoom party were clamoring for another online event in 2021, and we’re certainly considering this in addition to an in-person cake-tasting party. Last year’s roster of luminaries is a hard act to follow, and we’ll try to concoct a program that will be different but equally engaging and uplifting. It’s so satisfying to reach out to a community of Dickinson lovers beyond Harvard Yard, but who knows whether people will be able to stomach any more Zoom at that point. During the open mic portion of the 2020 virtual party, a number of attendees spontaneously shared their own music, poems, or visual art, and it was very moving. So we’re thinking that 2021’s event will more intentionally revolve around art. Perhaps a program will include artists whose work is inspired by Dickinson, and we’ll certainly invite the wider audience to create Emily-inspired art of any kind and share their work at the afterparty. We did a similar thing back in 2015 for our very first celebration, but we only solicited our Houghton Library colleagues, gathering about a dozen submissions in response to the Dickinson-style prompt:

Make something—anything—

Having something—

Anything—to do

with Emily Dickinson.

The little in-house art exhibition added something special to the novel black cake-eating festivities and was very well-received, so we’re thinking this will be a promising way to go for this December. It’s all about sparking creativity and engagement, and creating a sense of community, appreciation, and gratitude. Besides enjoying some wonderful poetry and some really good cake, of course.

Biographies

Christine Jacobson

Christine Jacobson is assistant curator of Modern Books and Manuscripts at Houghton Library, Harvard’s rare book and manuscript library, where she is responsible for stewarding the library’s collections from the nineteenth century through the present day. She also writes book reviews and convenes the Bookish Book Club, an international virtual book club for reading books about books.

Emily Walhout

Emily Walhout has had the great pleasure of being a reference assistant in the Public Services department of Houghton Library for over thirty-five years. Outside the library's walls she is a professional chamber musician specializing in music from the Renaissance and Baroque, performing regularly on bass instruments of those periods — viola da gamba, Baroque cello, lirone, and bass violin.

Automated Poetics