Fighting back

Lillian Allen's poetry of speech, song, and social justice

In 1984, following a tremendously successful year of touring and performing for large audiences across Canada in support of an album entitled De Dub Poets (1983), Lillian Allen, Clifton Joseph, and Devin Haughton sought membership with The League of Canadian Poets. The League is a Canadian literary organization whose mission it is “to nurture the advancement of poetry in Canada” and to promote “the interests of poets.”[1] As Allen recounts in Toronto-based This magazine, their membership applications were denied at a meeting in Regina, Saskatchewan that same year because the League did not recognize them as poets. Instead, they were distinguished as performers. “Are we all supposed to get up and do that?” one League member reportedly quipped.[2] In her poem on the Regina Affair, Allen refers to the League’s decision as an effort to maintain the Board’s firm grasp on literary power and what it meant to be a poet in Canada at that time.[3] It was a moment during which the board, comprised of persons trained in the British lyric tradition, attempted to maintain dominance over what Allen calls their “one poem town,” populated by a poetry that is predominantly white and Eurocentric in its model. After an outpouring of criticism against the League, which included accusations of racism from Allen’s supporters, changes were made to the Board and their original decision was quickly overturned. According to the League of Canadian Poets’ directory, Allen is still a member today.[4]

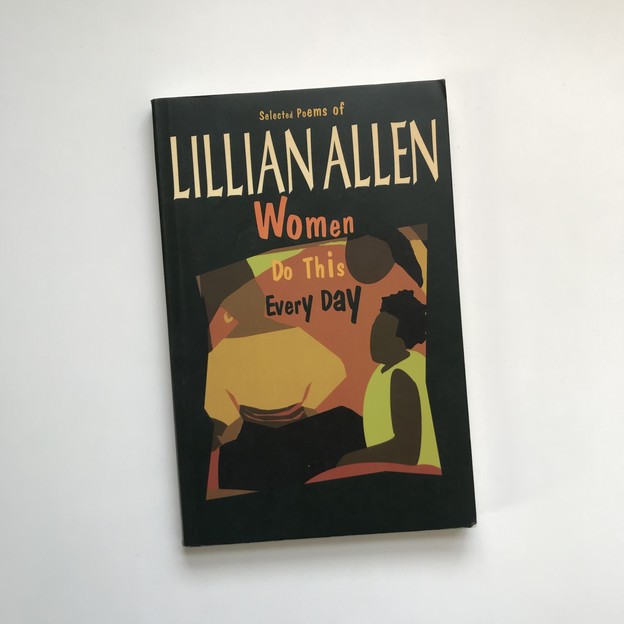

The decision to reject De Dub Poets’ membership application was an effort to deny them access to the institutional support the League offers to its members — funding, travel, event opportunities, programming, etc. This conflict resonates with enduring problems of power and access for poets today in Canada and the United States. Allen fights back with her poetry. She does so with a dynamic poetic of speech and song that combines spoken word and music to create what is known as dub poetry. Since 1984 Allen has been celebrated by creative communities as the recipient of two Juno Awards for Best Reggae/Calypso Album for Revolutionary Tea Party in 1986 and Conditions Critical in 1988. Despite this more mainstream recognition, Allen’s poetry has always served the cause of unsettling institutions that use their power to exclude, especially to exclude persons in vulnerable positions. This is repeatedly demonstrated in her numerous books, including Rhythm an' Hardtimes (1983), Women Do This Every Day (1993), and Psychic Unrest (1999), which contain poems that explicitly address issues of power imbalance, sexism, racism, and police brutality. Allen has also maintained a commitment to grass roots efforts, including small press and independent publishing ventures. Her albums, for example, have been released on her own label Verse to Vinyl. I could go on, but I will note finally that Jacket2 is also hosting an insightful talk by Allen from the 2014 Avant-Canada: Poets, Prophets, Revolutionaries conference at Brock University wherein she discusses the exclusion of dub poets and spoken word artists from literary communities.[5]

Allen’s video recorded 1988 performance of “The Subversives” at the Harbourfront Centre in Toronto demonstrates the social conscience of her poetry, and in that moment, advances the politics of her poetics. Here, Allen performed a version of “The Subversives” to a live audience that is double in length when compared to the 1988 audio recording on Revolutionary Tea Party. It is a ten-minute long version which includes an extended instrumental jam of drum, guitar, bass, and improvised vocals that bring the performance to a crescendo. As they begin the song, Allen calls for her chorus and requests that members of the audience come join her on stage to sing and dance. She asks the tech crew to turn the lights up on the stage, making visible everyone beneath them, and asks: “Everyone wanna joyful night? Everyone wanna make some revolutionary sounds?” And she calls specifically for women to join the stage. The performance is indeed joyful with over twenty people dancing together on stage, chanting the refrain: “We, we are the subversives. We, we are the underground.” The invitation that Allen extends to the audience to join her on stage is significant. Allen begins to take down the wall between artist and audience, between outside and inside. Under the lights of the stage, Allen assists in making bodies visible and present, bodies that otherwise may be unnoticed in the space. In this invitation I find a profound and necessary ethical gesture in Allen’s commitment to using her poetry to make space and celebrate others.[6]

1. Per their website.

2. Lillian Allen, “De-Dub Poets: Renegades in a One Poem Town,” This 21, no. 7, (December 1987/1988): 14–21.

3. Lillian Allen, Women Do This Every Day (Toronto: Women’s Press, 1993), 117.

4. See also Diana Brydon’s essay “One Poem Town? Contemporary Canadian Cultural Debates,” in Voices of Power: Co-operation and Conflict in English Language and Literature (L3: Liege, Belgium, 1997), 211–220.

5. See also Sarah Dowling’s accompanying response to Allen’s talk “Reloading the canon: On Lillian Allen and the history of dub” on Jacket2.

6. Portions of this post were first presented at the 2019 Modern Language Association Convention in Chicago.

Poetries of the Mouth and Canadian Imaginary