I know what debris looks like

On Matt Longabucco's 'M/W' (UDP, 2021)

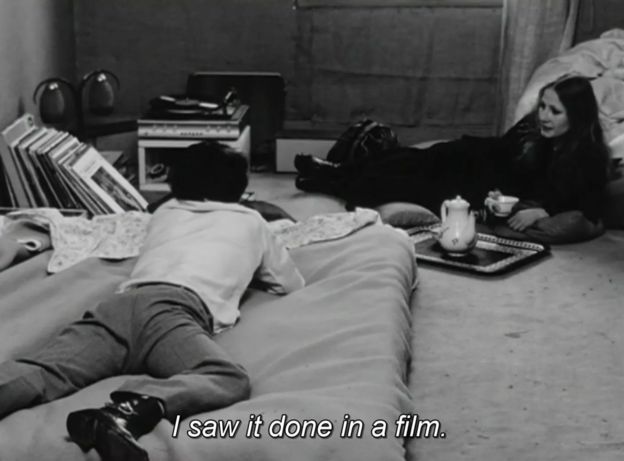

I came upon Matt Longabucco’s book of 2021 mostly by accident and could not stop reading its critical/personal prose poem sections. I had seen the film to which it is a thoughtful historical response but that was years ago. M/W: an essay on Jean Eustache’s La Maman et la Putain is a compelling — focused but also diffuse — response to the film, a great example of how in the field of contemporary poetics writers can contribute works of “close reading” (“close watching”?) that proceed from hybrid convergences of prose poetry, criticism, theory, contemporary politics, and personal reflection. Hilton Als, an admirer of the book (and that makes perfect sense), is right to describe this unusual work as containing “beautiful intensities.”

That Longabucco’s academic training culminated in a dissertation exploring the telling complications of difficulty makes sense as an academic preamble to a phase of a career of writing that has sought, at least as a theme, to start over literarily. Difficult modern writing isn’t difficult as writing but, rather, it is deemed “difficult” because institutionalized critical responses wanted or needed to construct difficulty as a category. So perhaps, leaving aside that critical gesture (certainly, at least in part, self-serving), we are back to writing that makes sense of us in times of crisis. This disposition is indeed a  main strength of M/W but also, just prior to that new work, of a poem of 2020. No wonder that The Brooklyn Rail in spring 2020 sought out Longabucco to comment in verse on that volatile moment — with “But I Have Always Been the Same,” which is in one sense a classic paratactic “New York meditation” (to use its own phrase) and, in another, a radical statement capturing the need to break away from whatever has been thought and written previously, prior to the seemingly insurmountable triple crises (pandemic, racist hatred, climate destruction): “it’s too late to read some of the volumes / I might have finished / back in the day when I could plow through anything.” One can only now, it seemed (and seems?), maintain one’s “legendary thirst” and “eat without ceremony,” and thus “sweep … away … these layers” of “another civilization” that had been botched. The state of the writer-intellectual is in the talent not for making new language but for “retract[ing] all the phrases and images I’d uttered.” Where to go now? Another work, Heroic Dose, seems to be another form of a way forward. It shows him leaning away from “authenticity games,” while continuing the lament of “But I Have Always Been the Same”: “I’ve read so many books,” he writes in Heroic Dose, “it’s like I’ve read none.” Such a self-critical stance augurs, I think, an attractive new sort of culturally responsive literary/readerly history, in which what is “too abstract” prevents us from knowing the terrestrial built realities of “the lintel of the window” and specificity of local psychosocial situations of “bros in the backseat of an uber / just giving up.”

main strength of M/W but also, just prior to that new work, of a poem of 2020. No wonder that The Brooklyn Rail in spring 2020 sought out Longabucco to comment in verse on that volatile moment — with “But I Have Always Been the Same,” which is in one sense a classic paratactic “New York meditation” (to use its own phrase) and, in another, a radical statement capturing the need to break away from whatever has been thought and written previously, prior to the seemingly insurmountable triple crises (pandemic, racist hatred, climate destruction): “it’s too late to read some of the volumes / I might have finished / back in the day when I could plow through anything.” One can only now, it seemed (and seems?), maintain one’s “legendary thirst” and “eat without ceremony,” and thus “sweep … away … these layers” of “another civilization” that had been botched. The state of the writer-intellectual is in the talent not for making new language but for “retract[ing] all the phrases and images I’d uttered.” Where to go now? Another work, Heroic Dose, seems to be another form of a way forward. It shows him leaning away from “authenticity games,” while continuing the lament of “But I Have Always Been the Same”: “I’ve read so many books,” he writes in Heroic Dose, “it’s like I’ve read none.” Such a self-critical stance augurs, I think, an attractive new sort of culturally responsive literary/readerly history, in which what is “too abstract” prevents us from knowing the terrestrial built realities of “the lintel of the window” and specificity of local psychosocial situations of “bros in the backseat of an uber / just giving up.”

And so now this book I came upon, M/W: an essay on Jean Eustache’s La Maman et la Putain (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2021). Eustache’s revered 1973 film (shot in 1972) responds, with a few years’ melancholic retrospection, to the hoped-for radical breakthrough of May ’68 (in Paris but also generally). The reassertion in post-68 Europe of authoritarianism and top-down politics — not just among conservative forces reacting to the cultural and political (and pedagogical) rebellions, but also among despairing radical-left groups and movements — creates a mostly unspoken backstory in this film of personal failed promises and sexual (counter-)revolution. M/W is in one sense a book-length series of critical/theoretical prose poems, each on a page, each assessing the film’s specific retrospection: 1972 looks back on 1968, and what does it see, and how does it feel about how sexual/romantic partners and affective combinations live daily life? One option would have been a critical close reading (or close watching) of the film — a book that draws its larger points by sticking with a single work of art made at a certain pivotal moment in time. In part Longabucco does indeed provide that. But what can a poet do — one who has their own experience to provide as a subject position? Can such a sense of the contemporary (let us say 2011-present, i.e., post-Occupy) shape a sense of 1972’s re-reading of 1968? Of course it can, and should openly (rather than through the making a typical critical undisclosed academic subject position). M/W makes what is typically covert into an overt conversation about our own response to resurgent authoritarianism, inequality, phobias over immigration, fears of real global interanimations among cultures, and anti-Blackness. 2021’s version of 2011’s version of 1972’s version of 1968 forms the experience of reading the frank disclosures of this volume. Important because we must know that our response to the counter-response to recent progressive democratic advances (marriage rights as perhaps one culmination of the "sexual revolution," the emergence of center-left “purple” states, effective movements such as BLM, climate change activism, etc.) aligns with a long specific up-and-down history of which The Mother and the Whore was and is an instructive point along the bumpy extended line. And, then, by watching the film closely, we realize that 1972’s disappointed response to May ’68 was itself a response to “the French Occupation [in World War II], and her [France’s, that is] subsequent engagement to France’s resignation, in the aftermath of those upheavals, to disappointed mediocrity” (p. 30). (In an odd way, La Maman et la Putain is a follow-up to Chronicle of a Summer of 1961, with its mumbling cinéma vérité [non]script constituting an effort to connect the disastrous French role in the genocide of WW2 directly, fifteen normalizing years later, to the last ugly gasps of colonialism in Algeria. The hip conversationalists of Chronicle are exactly as disheartened — and disheartening to us later — as Eustache's people.) Longabucco’s book, by itself being intentionally the antithesis of mediocrity, helps us ward off the post-radical blues and does so, in part, by being responsive writing. “RIDDLE: Why write or read about a movie, rather than simply watch or re-watch it? Why talk [e.g. as he in this book is doing, a great deal] about love when everything you say will be a lie...?” (p. 26) This is a strong and, to me, persuasive motive for making art, an ars poetica that refuses to let writing relinquish its radical critique.

The downbeat “I” of M/W could at any point be the flawed early-seventies Parisian guy, Alexandre, speaking to us through Longabucco’s text, but we know it is also the present writer — frank, chastened, seeking motivation. The honesty is hardly filtered through the fictive focalizer of the film, and this is what frees Longabucco to be so interestingly personal and perhaps to some extent to speak for a generation intellectually and aesthetically coming of age in the late 00’s and 2010s.

I was looking for something better, more free and alive than the role I’d been handed: clumsy and inarticulate thing.... I know what debris looks like, and how shiny it was at the start, and I know what the movies know too, and knew it all along, but I had to live a lot in order to learn how to watch them, rather than watching them, as Alexandre says misleadingly, in order to learn how to live. (p. 108)