The artist's book, informed

Conceptual approaches in the handmade artist's book

My last post explored book artists who work conceptually using print-on-demand technology, but the use of conceptual methodologies extends to those who work in hand-made books as well.

This summer and fall, I have spent time in special collections at the University of Washington (partly in preparation for the Affect and Audience in the Digital Age symposium, and partly to find books for my spring workshop). My next several posts will feature several book artists from among the library's holdings whose work engages with language as data or information, much like those book artists working in the Ruscha tradition of catalogue and documentation.

Tony White

Mentioned in my last post for his theorizing of trends in contemporary "artists' publishing," a subject that comes up in his current blog for Camera Club New York (check it out soon, his stint ends at the end of the year), White is a book artist whose body of work encompasses the ephemeral (text pulped, cooked into jam, and consumed by a cohort of student artists) and the eternal (a set of "pulp" paperbacks) that have been pickled for posterity:

Tony White, From the Literary Kitchen of Tony White (1992), UW Libraries Special Collections. Photographed with permission of the artist.

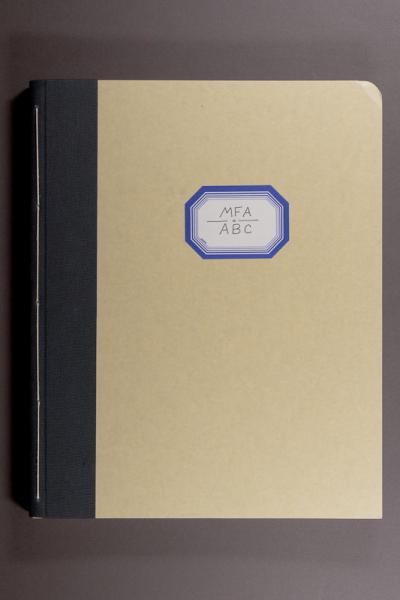

I was intrigued when I came upon his MFA ABC (2001), pictured below. The concept is deceptively simple, as explained on the book's second page:

This is an alphabetical list of words used in 166 artists' statements. These statements, along with their photographs, were "submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut on [a date and a year] by [artist name]. Major in Photography." The statements date from 1971 through 2001.

Tony White, MFA ABC (2001). UW Libraries Special Collections. Photographed with permission of the artist.

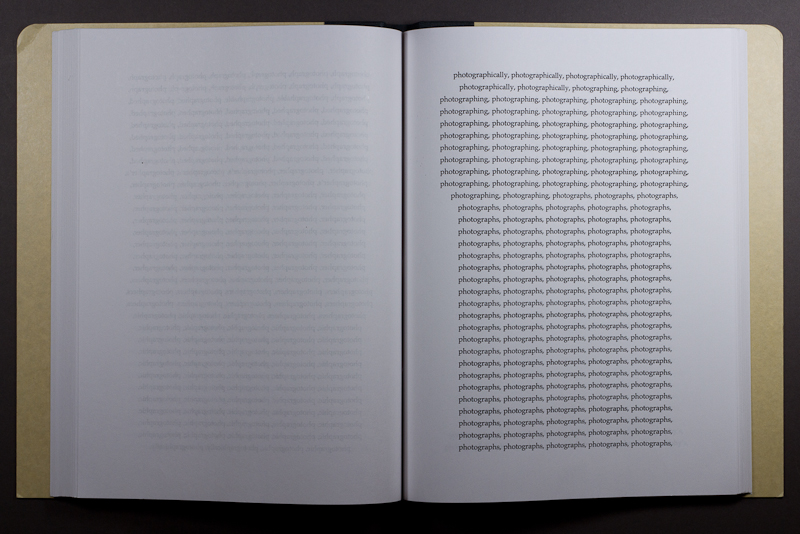

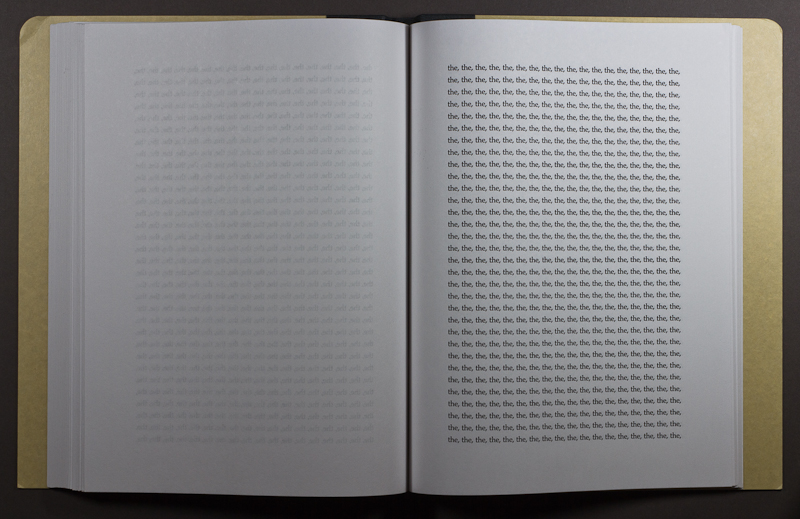

The book, bound in what looks like the sort of archival case in which such a thesis might be filed, contains exactly what it purports: an alphabetized word list—the ABC of the MFA. Though stripped of context, the work bears traces of its academic-theoretical intent in the language that surfaces upon reading. The text is, in fact, all surface, and while it does not provide a deep reading experience, it is still a mesmerizing one. Alphabetizing the contents unifies what we presume are diverse sources into a collective voice, leveling the text both thematically and visually. Because the typescript is monospaced, patterns emerge. A page of "the" iterates nothing but itself, presenting an opaque wall of language. The word "and" provides more than three pages of hypotactic delay. The words that normally serve as mortar become brick, lending integrity to even the tiniest article used to buttress these artists' statements. Yet it becomes clear in flipping through this text that the anonymized sources share a concern with medium—not their material medium, but in fact their artistic medium, photography, a term that shows up in numerous variations (photograph, photographs, photographer, etc.—enough to fill more than 5 pages). These artists have learned their ABCs, and they namecheck the requisite terms to demonstrate their familiarity with their field.

In another context, this would be a digital humanities project (revealing the most and least common terms, recurring themes, and likely pairings), or perhaps the database for one of the many "artists' statement" generators now found online. It can be read as a satire of the MFA, but also as an anthropological study, like Mark Rutkoski's conceptual Words of Love (Les Figues Press), an alphabetized frequency index of all the words in Shakespeare's sonnets.

A colophon at the back of the book lists the names of each artist whose work White scraped, and documents the process of the book's creation. One expects to find that these theses were simply copied and pasted into a program that quickly sorted them alphabetically (one can find many such tools online), but the process was, in fact, one of methodical typing:

I started this book in June of 2001 and finished about one year later. During the entire summer I visited the Art of the Book collection 2-3 times per week on my lunch hour. I made photocopies of every single artist statement. During the fall and winter, I retyped all the artist statements. In order to sort all the words alphabetically in my word processing software I had to type one word at a time; then a comma; then hard return. In effect creating a single column. After typing about 15-20 pages at a time I would sort the text alphabetically. In the early spring of 2—2 I finished the data entry and began formatting the document: from a single column to paragraphs.

I used a Macintosh G-4 with Microsoft Word 6.0.1. The type is Palatino. There will be a lettered edition (A to Z) with cloth spines and 40 pt. board covers. The text block will be perfect bound with PVA and then pamphlet sewn for strength. While the library binding is not "pretty" it is functional and, I feel, conceptually in line with the project.

This "lunch poem," refuses to be digested. Its very process requires the artist to "process" the work of his predecessors in the same fashion as the work of contemporary conceptual poets.

When I emailed White to ask about the painstaking work that went into crafting this apparently-craftless artifact, he explained:

"When I made the MFA ABC book, I was working at Yale University Library in the book and paper conservation lab. I was making very little money and only had access to my Macintosh Classic computer that I had been dragging around since 1991. Yes OCR technology was available, but it was very imperfect at that time, and I was told the cleanup would be very time consuming. A few friends also suggested I collaborate with a computer programmer, but I did not know anyone who could help. Plus I did not mind the process."

The book is now abvailable in hardcover on lulu.

Selected Further Reading:

Artists' books in the age of digital publishing