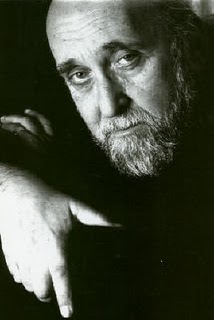

Jerome Rothenberg, 'A Paradise of Poets'

LISTEN TO THE SHOW

Bob Holman spent a few hours away from the at-times paradisal Bowery Poetry Club to help us (PoemTalk regulars Jessica Lowenthal and Randall Couch) figure out what sort of beloved community Jerome Rothenberg had in mind when he wrote his possibly programmatic poem, “A Paradise of Poets.” He published this short poem in a volume called Seedings and only then, a little later, published the book called A Paradise of Poets (which lacks the title poem). Confused? Please don’t be. The poem is a working out of the major preoccupying themes of the book that followed.

Bob Holman spent a few hours away from the at-times paradisal Bowery Poetry Club to help us (PoemTalk regulars Jessica Lowenthal and Randall Couch) figure out what sort of beloved community Jerome Rothenberg had in mind when he wrote his possibly programmatic poem, “A Paradise of Poets.” He published this short poem in a volume called Seedings and only then, a little later, published the book called A Paradise of Poets (which lacks the title poem). Confused? Please don’t be. The poem is a working out of the major preoccupying themes of the book that followed.

And what a book it is! In A Paradise of Poets we re-visit Paradise…err, sorry…Paris, where the ghosts of JR’s modernist forebearers (the generation of 1910, he says) appear to him in the guise of Left Bank street people, well dressed but destitute. He anticipates his own demise; he is lonely yet surrounded by the voices of poets he admires. And he realizes that a paradise of poets is only possible when one poet’s line stops just as the next poet’s line continues, a “line” indeed, as in lineage.

Bob, Jessica and Randall agree in our discussion that this is a heartfelt conclusion and that it must come in stages, beginning with the sort of poetic narcissism under the spell of which the poet believes that no one else can write his poem, even as he is writing over (literally on top of) that of his predecessor.

The world will not end when he does.

Asserting the centrality of such connectedness, Jerome Rothenberg, it was said by Allen Ginsberg, saved us all twenty years. Or, as Bob Holman put it, “He was Google before there was Google.”

May 28, 2008