Modern myths and topographies

Julia Bloch

Editor Julia Bloch reviews four poetry titles that make us think differently about spaces both crowded and open, and histories both told and ready to be rewritten.

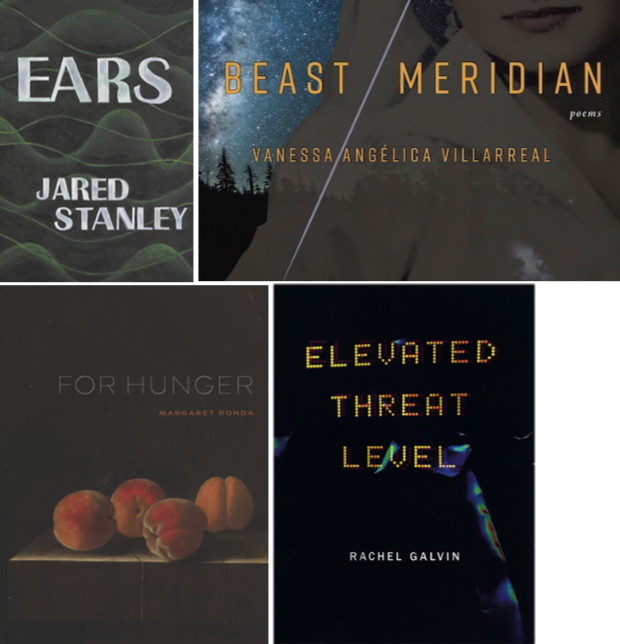

Ears, Jared Stanley (Nightboat, 2017)

“The / poem wasn’t / supposed to be / polemic, it was / supposed to be / about ears finding / their independence / from the will,” Jared Stanley writes in Ears, in which mostly declarative lines delight in their ability to hone in on small surfaces and then swerve out again to deliberative and sweepingly observational registers. A single poem called “The Listening” opens with the cilia’s ability to hear friendship in a scavenger bird’s squawk and ranges into an exegesis of the outer limits of friendship and fate, domestic grime and the harsh life of the Sierra Nevada desert, personality and impersonality. As much as personhood startles up and wanes in this collection, Stanley’s poems retain a fine, physical intimacy. “Relax,” the speaker says; “This specific / emptiness (the / desert’s) is not / about you, it’s / about nobody.”

Beast Meridian, Vanessa Angélica Villarreal (Noemi, 2017)

The poems in Vanessa Angélica Villarreal’s Beast Meridian alternately lull and thrill with mythographical bestiaries (“Asi, mijito: discard the beak & the wattle, the tumored skin hanging from the chicken head”), genealogical interventions (“I inherit a palace of locked doors”), anticolonial laments (“each red egg a hatching star in my hair, / each surface of my life a border and singularity: / the migrant heart sliced into petals by guitar string”), and radical reimaginings (“But as the years pass, the girl unspools animal after animal from her halo and writes its story into her sky”). The poems’ typographical range enacts a series of material excursions into the tensile limits of language’s boundaries: dashes, brackets, slashes, numerals, footnotes, typeovers, caesurae all interrupt and propel the poems forward, while a series of family photographs both anchor and torque Villareal’s historical poetics.

For Hunger, Margaret Ronda (Saturnalia, 2018)

Many of the intensely visual, often concentratedly affective poems in Margaret Ronda’s For Hunger read both as parable — “The baby wants to be fed but the mother is sleeping. The baby needs a new language” — and contemplative daybook — “Today a debt to eat or let rot in the cupboard. Yesterday a body growing distant, earthward. To love is territory and darkness.” Shot through with luminous imagery, Ronda’s poems often burnish their objects only then to render them in vaguer edges, as if the poem needed to veer differently to make its most accurate argument. The book harnesses the power of the elliptical even in proselike lines that gesture toward story. Especially striking is the longer poem “Apple Cake,” which in its narrative omissions draws us toward the shapes of language and story left behind. When the language pulls back in these poems, it’s at just the right moment to let the reader in.

Elevated Threat Level, Rachel Galvin (Green Lantern, 2018)

About a third of the way through Rachel Galvin’s Elevated Threat Level, a poem called “Gutenberg Nation” catalogues the death of eleven US newspapers and the slogans of others, from the Atlanta Journal Constitution’s “Covers Dixie Like the Dew” to the Aspen Daily News’s “If You Don’t Want It Printed, Don’t Let It Happen.” Galvin’s piercingly alert elegies, sonnets, and documentary poems record and refract a series of brutalities, from the murder of journalists to the sly machinations of private equity to the meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant to sorrows recorded by a host of other artists and writers, including Anselm Kiefer and César Vallejo. Each poem makes its own case for how the work of recording history can change our perception of ourselves and others, beginning with the book’s opening poem: “My eyes are polished smooth by sight. They clot like crystals in storm glass, / like beakers of toxin. If we had seen what had been done, / what the helicopter pilot did in our name, // what the special ops team did in our name, what they did / with their hands in our name. What if it were my sister, / what if it were her, what?”