Yong Shu Hoong

On the [unofficial] 'Reluctant Yuppie' and 'Reluctant Soldier' Schools of Poetry in Singapore

Yong Shu Hoong is the author of five poetry collections, including Frottage (2005) and The Viewing Party (2013), which won the Singapore Literature Prize in 2006 and 2014, respectively. His poems and short stories have been published in literary journals like Quarterly Literary Review Singapore and Asia Literary Review (Hong Kong), and the anthologies Language for a New Century (W.W. Norton, 2008) and Balik Kampung (Math Paper Press, 2012). He lives in Singapore, where he works as a freelance writer and teaches part-time in tertiary institutions like Republic Polytechnic and Nanyang Technological University (NTU). He was writer-in-residence at NTU from August 2013 to February 2014.

You can listen to Yong Shu Hoon read the poems featured in this interview.

Divya: Shu Hoong, I’ve been thinking about your poem “Hazards Related to the Setting up of a Christmas Tree” ever since I heard you read it at the Singapore Writers Festival last year:

Hazards Related to the Setting up of a Christmas Tree (Listen)

Today, I receive a circular with this warning:

As we celebrate the festive season, it is important

to be aware of the possible hazards…

Yes, the evergreen conifer looks benevolent, but

we should still keep in mind these safety tips:

1. Use Christmas lightings with the approved

Safety Mark. (This applies also to the use of plugs

and extension cords.)

2. Always check for blown bulbs, cracked sockets

and worn cables. (Poorly maintained lighting fixtures

pose a high risk of fire and electric shocks.)

3. The Christmas tree and decorative light fixtures

shall not be placed in such a manner that it obstructs

emergency paths to escape job-related tedium.

4. Check and ensure wirings do not cause tripping,

though you are allowed to trip the light fantastic, once,

after the annual report is signed.

5. Always be sure to turn off the tree lights before leaving –

unless you decide to never return to the office, for good,

and to bow out with a final act of defiance.

6. Always keep water sources away from the Christmas

tree (no matter how much you are tempted

to offer alms to the poor).

7. Always place a fire extinguisher near the tree, in case

it combusts spontaneously with the shame of an advent

candle that has forgotten its preparations.

Divya: What struck me right away was the tone used by the “circulars” that the poem references— that strange bureaucratic document— equal parts benevolence and authoritative brusqueness. The effect is both hilarious and somewhat melancholic. The ‘circulars’ I’ve received are routinely paranoid— they suck the joy of out everything and expose the darkest sides of happiest occasions, just as your poem demonstrates, quite gleefully. The poem shifts away from your other work, which seems to feature a fairly stable, lyric, “I” as the primary speaking position. Could you talk about the list form and documentary-style textual appropriation in this particular poem? What does this form and aesthetic mode make possible for you?

Shu Hoong: Yes, I have to admit that I use “I” a lot in my poems. The “I” would be around 90 per cent autobiographical, tempered sometimes by a need for a little exaggeration to heighten emotional and dramatic effects.

It’s interesting that you mentioned that “Hazards Related to the Setting up of a Christmas Tree” felt like a shift away from the style of my other work. Coincidentally, I have recently been thinking about what I can do to move away from writing poetry too much in the first-person perspective. But this particular poem wasn’t written consciously with that intent in mind.

In the course of my stint as the writer-in-residence at the Nanyang Technological University (NTU) in Singapore, I was accorded the status of a full-time staff, so I got all kinds of mass email circulated to the staff list. On 17 December 2013, I received an email from NTU’s Office of Health & Safety (OHS) with the subject “OHS Alert 56 – Hazards Related To Christmas Tree Set up”. It read:

Dear All,

As we celebrate this festive season, it is important to be aware of the possible hazards related with Christmas tree set up. Please refer to attached file for more safety tips when maintaining your Christmas tree.

My curiosity was aroused. I wondered, what hazards could be associated with the Christmas tree, a benign symbol of festivity and celebration. Naturally, I opened the file to find out more. And from the seven safety tips that were given, I appropriated and deconstructed them to form my poem.

The first two tips were presented almost word for word, save for some minor editing. For some reason, my recent poems have the tendency towards found poetry, where text was appropriated from sources ranging from the Bible to an online job ad.

From the third tip onwards, I began to meddle with the words and meanings, and in a way, the tips became my own advice to the reader “to escape job-related tedium” and “to never return to the office”. On hindsight, I think this is my tribute to the “reluctant yuppie” school of poetry that I used to dabble in when I was still working in the corporate world (I worked six years in the banking industry before becoming a freelance writer and part-time lecturer). Ng Yi-Sheng, in a book review of Toh Hsien Min's Means to an End (2008) in the Quarterly Literary Review Singapore, describes such poetry as “meditative segues about disillusionment with office life”.

Towards the end of the poem, the tips seem to take on religious undertone, where I begin to question the meaning of Christmas.

Aesthetically, the list form is reminiscent of what you’d find on a Powerpoint slide or an officious memo. But I have standardized each “safety tip” to three lines, so that when taken as a whole, the tips read like seven uniform-looking stanzas. This might be seen as another departure – when compared to a lot of my recent poems where lines are presented as a single block with no breaking into stanzas.

Ultimately, this poem is less about form, but more about subverting a memo and finding a sense of humour and poetic grace in the authoritative and mundane list of do’s and don’ts.

Divya: In Singapore, I’ve noticed that the majority of the poets I meet work a day-job, where they crunch numbers or work out algorithms or sketch business plans. But, there are also a remarkable number of people who have chosen to become freelance poets and writers— an unimaginable possibility in the United States, unless one is quite independently wealthy. So, I’m intrigued by what you refer to as the “reluctant yuppie” school of poetry— it has certain cross-cultural implications, but also has a distinctly 1990, turn of century stain to it, right? And this is despite the fact that Time magazine published a mock obituary to the Death of the Yuppie in 1987. The term seems to have a kind of elasticity and resilience— still hovering or threatening the artist’s identity: it is a kind of soft nightmare of what we might become if we let our guards down.

In the U.S, my own context for the yuppie stereotype has been folded into a broader category of being a “tool”, I think— referring to someone to works for The System (capital S) without questioning it, or without being able to challenge it. The role of the University within this framework is increasingly one of complicity, of course, with increased privatization and multiple threads of accountability to corporate interests— the Ivory Tower is now just Takashimaya or Shaw Tower and so on.

Could you say more about how that stereotype (“the reluctant yuppie”) and your decision to leave the corporate world? What did you leave it for? If “poetry”— what has that word entailed for you— certainly more than writing and publishing? What has this change in realms made possible for your own living and being in the world?

Shu Hoong: I’ve never really thought about the word “yuppie” in terms of its origin, or its time of origin, but it could well be a term that came out of the 1990s. I wouldn’t be at all surprised to find it in Douglas Coupland’s 1991 novel, Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture, which I quite enjoyed reading way back then.

I guess, relooking at the definition of “Generation X”, I would place myself and a lot of the contemporary Singaporean poets who had come into prominence around the same time as me in the late 1990s – like Aaron Lee, Alvin Pang and Cyril Wong – as being part of that generation.

It’s true that most of us hold some kind of day job – in some instances, very lucrative ones. Among the poets, there are lawyers, full-time teachers or academics, journalists, professionals in the financial industry, as well as high flyers in the public sector. Then there are the freelancers – who write or teach – that get by somehow, without becoming too much of a suffering artist.

Armed with my computer science degree from the National University of Singapore, I first started my working life with a Singapore bank as a system analyst/programmer – a job that I had clinched even before my graduation ceremony (the economy was rosy in the early 1990s). Restlessness took hold of me after a year, and before the second year was up, I had decided to leave the company to do my Master of Business Administration at Texas A&M University at College Station in the United States. I had also wanted to spend the next one and half years overseas, for a change of environment – which ended up inspiring me to start writing poetry and, subsequently, to publish my first book, Isaac (1997).

By the time Isaac was out, I had already gone through another job in IT and made the switch to multimedia and online journalism. “The Sobering Age”, from Isaac, is a prime example of my take on “reluctant yuppie” poetry, questioning: “Isn’t it too early to feel jaded already / since it’s before the appropriate age?” It touches on the negative effects of an office job – wrinkles (from work-related stress, presumably) and fat accumulated around the belly, before ending off with:

But the women reassure you that they

did not see the premature greying of hair-roots.

As long as the wallet is fed. And for that reason,

you straighten your tie and remember work.

After making a brief foray into the exciting dot.com industry, I found myself back in another bank doing web content and product marketing for online banking – right until 2006 before I left my full-time corporate toil completely. In the more recent collection, The Viewing Party (2013), a prose poem titled “Sugar Fix” reminisces about “that past life”, bridging the past and the present life marked by a different happiness:

In that past life, drunk on after-lunch lethargy, I’d sneak away from work, walk a bloated circle before finding a convenience store stocking what I craved. Sleep dissipated by the time I backtracked to my office, I’d leave the chocolate bar untouched upon my desk for the weeks following. Now, I hoard happiness differently: At a cafe having a cup of latte, I steal sugar for my dining table at home. I contemplate equating such transference with money laundering, while powering up my laptop. I don’t play computer games, but derive amusement discovering forgotten sachets within backpacks and worn garments.

Leaving my last job at the bank reflected dissatisfaction on my part, of course. But it had to do more with a certain level of boredom and a realisation that “there’s more to life than this”, rather than actual suffering. Even if there’s any kind of suffering or sacrifice involved, it’s a fair trade for the financial security that the job had accorded.

While people might envy me for the courage to leave the corporate world and embrace a seemingly bohemian lifestyle, I have to admit that I was still pragmatic enough to ensure that a large part of the housing loan on my apartment was paid off before I turned to freelancing. Fortunately, despite initial trepidation, I was able to make enough to make ends meet through jobs that came my way: freelance writing for The Straits Times, as a coordinator for a mentorship programme organised by the National Arts Council, as a part-time instructor at a polytechnic, and so forth.

The result is a better quality of life and greater flexibility to plan my own time. There were stretches when I got even busier freelancing than working full-time, so it wasn’t so much a need to leave full-time work in order to write more or to write better as a poet. My theory is that, if you’re constantly bored with work, you might just end up being more creative – since you’ll be just dying to write and express yourself creatively, the moment you get any free time. It really boils down to time management.

As for quality of writing, I can’t really say if there was a major change before or after I quit the corporate world. Frottage was released in 2005, just prior to the start of my freelancing life – it received good reviews and won the Singapore Literature Prize in 2006. Since then I’ve released two more books – From within the Marrow (2010) and The Viewing Party (2013), which won the Singapore Literature Prize in 2014. I’m hoping the quality of my poetry hasn’t suffered in any way.

Divya: I appreciate what you’re saying about boredom leading to creativity. The German philosopher and cultural theorist Walter Benjamin wrote—and this has stuck with me during those tedious years as temp worker and grader— “Boredom is the dream bird that hatches the egg of experience. A rustling in the leaves drives him away.” It also reminds me, of course of John Cage’s axiom on repetition and duration, which was influenced by Zen practice: “If something is boring after two minutes, try it for four. If still boring, try it for eight, sixteen, thirty-two, and so on. Eventually one discovers that it’s not boring at all but very interesting.” But, conversely, I think these two thinkers’ emancipatory claims become quite complicated once we contextualize them within the numbing hyper-surveillance of the workplace today.

It is not surprising to me that your poetry acknowledges working conditions in multiple ways. After all, Singapore is constitutionally built around an ethic of handwork and meritocratic ascent into the middle-classes. And this is certainly the case in one of your very poignant, precise poems, “Beyond Economical Repair,” in which you consider a rather different kind of labor— that of National Service.

Beyond Economical Repair (Listen)

All that’s left

of my service to the nation:

A broken watch.

But according to Hamilton’s

website, their watches

have unique personality

tempering the American spirit

with Swiss technologies.

Mine has a personality

that is only so-so.

Its glass cracked

at the slightest

confrontation. Is the mettle

of a Singapore soldier that

fragile, that he (and his Badge of Honour

upon the wrist) couldn’t quite

stand up to peacetime’s wear

and tear?

I stare, hapless,

at the watch-face embossed

with the Army’s crest,

partially obscured by the fracture

across the glass, the Joker’s

smirk.

Flipping the watch

over, I’m greeted with promises

that mean nothing now:

genuine leather,

stainless steel.

My full name

is engraved

on the back case

with last-attained rank.

Two and a half years

of active duty,

and a decade more

on the mobilisation list,

boil down to only this.

Divya: The poem brings up, for me, the historical association of trench art— decorative arts made by soldiers during conflict, with the scraps available to them in times of great scarcity or stress. Singapore hasn’t seen military conflict since independence in 1965, but all male citizens and second-generation permanent residents have to contribute to the Nation’s security and defense. So, most Singaporean men have this as an emotional and ideological link. Could you tell us more about this “service to the nation” and how it affects your understanding of masculinity and male-community in Singapore? Has it had an impact on Singaporean literature?

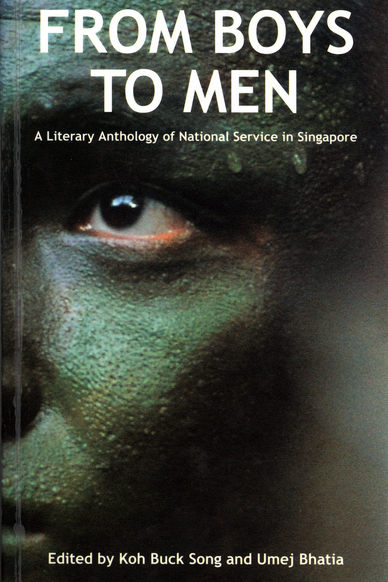

Shu Hoong: With National Service (NS) leaving an indelible mark on the formative years of male Singaporeans (typically, we get drafted at the age of 18), it’s only natural to find the subject featured in the poems of many male poets here. An anthology called From Boys to Men: A Literary Anthology of National Service in Singapore (2002), edited by Koh Buck Song and Umej Bhatia, provides a range of literary responses, including poems from the likes of Boey Kim Cheng, Koh Jee Leong and Gilbert Koh.

In a review published in Quarterly Literary Review Singapore (April 2003), Zhang Ruihe wrote that the book “is a kind of Singaporean bildungsroman, in more ways than one. At the most basic level, it examines the journey from innocence to experience that all NSmen have to go through. At times this involves a triumph over danger, whether real or imagined, as in Dheeraj Bharwani’s ‘Misfire’, a short story about a young second lieutenant who has to detonate a misfired round on his twentieth birthday. At others the feeling is not one of triumph, but of quiet reflection on ‘the sense of tragedy’ that undergirds the fact of mortality, as in Toh Hsien Min’s ‘Casualty’, about a soldier who dies of a mysterious illness.”

My poem “Green Days”, from Isaac, attempts to sum up my fascination and tedium related to serving the nation:

After a long sabbatical

arresting the grey cells,

all I can remember of the army are:

the windswept corridors

the virgin kiss of a cigarette’s butt

the beginning of beer’s aftertaste

curse words in a multiracial society

varying lengths at the showers

a full back of tattoos

invaded by bed bugs

and never staring

at the clock face

so hard.

Maybe this is the “reluctant soldier” school of poetry. But growing up in my household, where my parents are generally approving of government policies, I didn't seek to question the right or wrong of compulsory conscription. Instead, it was accepted as a challenge, alongside other phases of coming of age, without too much whining. To toughen up in advance, I even enrolled in the National Cadet Corp, a uniform group that was among the extracurricular activities offered at my secondary school.

I might not be very athletic, but I think NS has, in some ways, instilled in me the tenacity to tolerate hardship and overbearing people – from seemingly sadistic sergeants, to clueless officers.

My primary and secondary schools were boys’ schools, so I was already familiar with all-boys environments. But being in the army opened my eyes to the values and behaviours of fellow conscripts from different walks of life. A large part of my NS days was spent in my assigned army unit as a vehicle mechanic, with my dirty overalls and greasy toolbox. Being one of the few with a GCE A-level certificate, I interacted with great interest with drivers and fellow mechanics whose education level ranged from secondary school dropouts to holders of GCE N or O-level certificate.

In their midst was a guy who had worked as a temple medium, and gangsters with tattoos. Most of them chain-smoked, swore in Hokkien (a Chinese dialect with expletives also understood by non-Chinese soldiers with Malay or Indian ethnic backgrounds) and often boasted of their sexual conquests involving girlfriends and prostitutes. I guess it doesn't get any more macho than that.

DISCOURSES ON LOCALITY: Singapore