Pooja Nansi

On the whalesongs of Bollywood, sentiment, and the lyric familiar

"Listening to Mukesh"

Pooja Nansi

Driving to your block,

I slide in my father's cassette

of old Hindi songs and

I am humming in twilight

to the legendary

playback singer's baritone

releasing those sounds in that

language that makes me feel like I am

home. In the back of my throat,

I can taste my grandmother's

translucent thin chappatis

that as children we would

hold up

to the light,

the dough so evenly rolled out

by her hands that not

one lump would show.

I never appreciated them till her hands

shook so much,

she could no longer grip

the rolling pin.

I hear the children from the slum

that emerged behind my grandparents small

two-storey apartment block.

They are swearing

in that deliciously punctuated rhythm

only the born-and-bred tongue

can dance to.

I am home for a while.

I can smell dust and kerosene

in the air and hear

high-pitched devotions to the gods

blending without objection

into the stone thud bass

of the latest film song.

Jamming my brakes at a traffic light,

I realise home is supposed to be these

dustless streets and the smells

are alien culinary concoctions,

like pigs' knuckles and chicken anatomy,

that my migrant tastebuds

cannot migrate towards.

I have taught my tongue

to like the garlic sting

of Hainanese chili paste

and form some Hokkien curse words.

It even enjoys the harsh bite of it,

but it is not

a taste, a language

that makes my heart sing

like these notes on my

car stereo.

Jaoon kaha batayen dil,

Duniya badi hain sangdil

Chandini Aiyen Ghar Jalane

Sujhe Na Koyi Manzil.

Tell me where I should go

in a world filled with indifference.

The moonlight filters into my house,

But I do not belong,

neither can I think of a destination.

You can listen to Pooja Nansi read the poems featured in this interview.

Divya: Pooja, I came to your work through one of your early poems, “Listening to Mukesh”, in which you recall playing your father’s cassette tapes in your parked car. In this poem, you write:

I have taught my tongue

to like the garlic sting

of Hainanese chili paste

and form some Hokkien curse words.

It even enjoys the harsh bite of it,

but it is not

a taste, a language

that makes my heart sing

like these notes on my

car stereo.

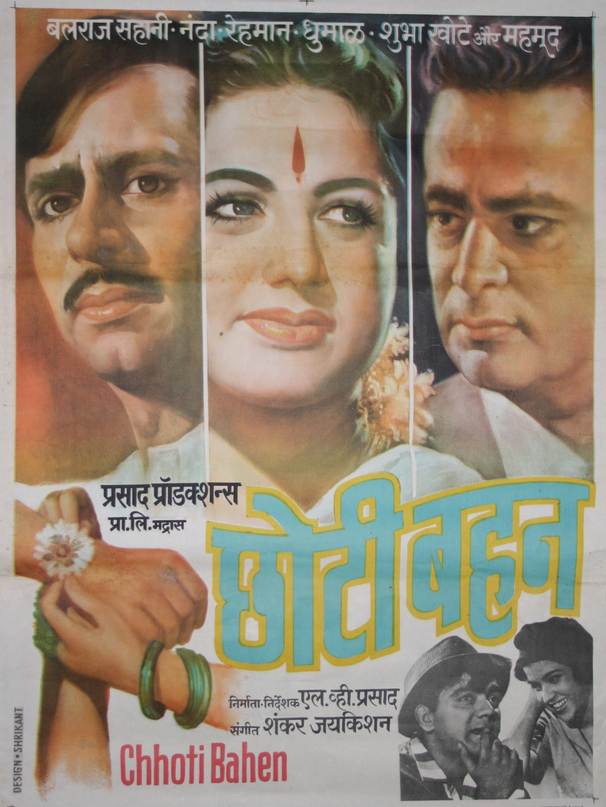

And you follow this admittance, this risky confession, by singing and citing Mukesh, the beloved Indian playback singer and legendary surrogate voice of Raj Kapoor. And you draw from his “Jaoon Kaha Batayen Dil” from the film Chhoti Bahen (1959)

Jaoon kaha batayen dil,

Duniya badi hain sangdil

Chandini Aiyen Ghar Jalane

Sujhe Na Koyi Manzil.

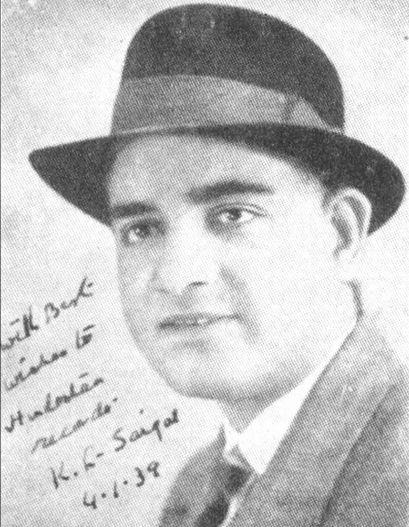

The figure of the tongue that tastes and the tongue that sings in a language one can call one’s own (or one’s home) returns again in a more recent poem, “k.l. saigal’s photograph in my grandfather’s closet”.

k.l. saigal’s photograph in my grandfather’s closet

At 42 he drowned himself to death

in alcohol. Loved music, with an intensity

he could no longer contain.

At 83 when you died,

we found a picture of him

tucked behind the three shirts and four pairs of pants

in your green metal Godrej cupboard.

You had a love affair with the man’s voice

burdened like pregnant thunderstorms,

each note crying for a loss that bore too heavy,

too dull and sharp all at once on his heart.

Tonight I chanced upon the track by accident and listened

with a growing lump in my throat to the voice that raised

goose bumps on my arms. Each one screaming like

a peacock

in resistance to the pain, asking

When the heart itself is broken

Why go on living?

When the heart itself is broken?

And I wished you back with all my heart,

wished us back to that tiny room in Worli,

You in your white linen kurta pajamas

seated one foot on knee in your torn leather chair.

Me sprawled by your feet on the green speckled floor

next to the old JVC radio.

I wished us back dadaji.

Because like you,

I know now

that the saddest sentence in love is

It’s too late.

It’s too late.

You describe your grandfather’s “love affair with the man’s voice”— and it is an intimate one, embodied in the photograph “tucked behind the three shirts and four pairs of pants/in your green metal Godrej cupboard”. Nestled in the soft, familiar folds of family, these iconic voices of Bollywood resound like whalesongs, echoing in your poems, calling us in two directions— back to a domestic past and a political future where we might belong. Tell me more about your own “love affair” with these voices— how did they bring you to poetry, to your family, to your voice?

Pooja: I’ve grown up always having music playing in some form around me. Both sets of grandparents and my parents loved music and it was always in the background playing while my mother would be cooking, or when my father was driving us somewhere. One of my most vivid memories is of one of our many visits to my grandparents in Bombay and there was a channel that would only play old Hindi songs (kind of like MTV when it still played music) and my grandmother would have that on while doing her embroidery or crossword puzzles and she would sing along in her warbly voice.

You put it beautifully Divya, in that they are whalesongs for me. My grandparents have all passed on and I can’t see them or smell them, but there are some songs that tug me right back to being 7 or 8 and being in that house and it helps me locate where I came from.

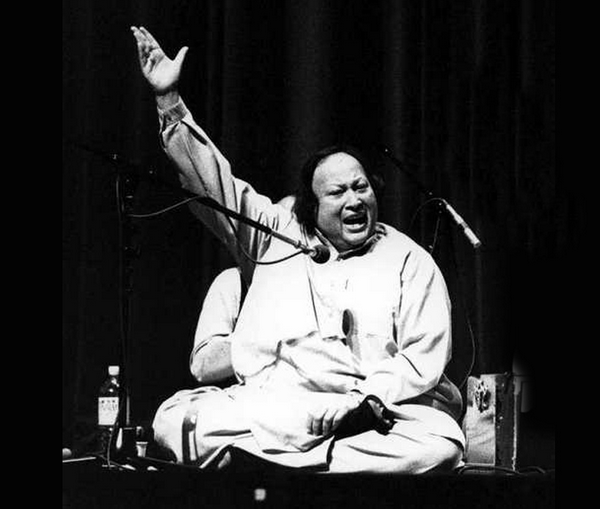

I grew up constantly hearing old Hindi songs, and Ghazals and Qawwalis and my father was my biggest source of supply for this music. So in a sense, his love affair has become mine. He has a massive collection of music and some amazing stories to go along with it. As a teenager he would record music off the radio on to tapes and I remember the annual exercise of cotton and alcohol as he made sure fungus stayed off his cassettes. When we moved to Singapore, he would go to the one store that had a good collection of Hindi music. It was called Lata Music Centre, and it was there that he once met the late, great, Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan himself before the man was famous. When he found out my father had been religiously buying every release of his, he took my dad to lunch.

I could listen to my father’s stories that accompany each song forever, and I could listen to him sing those songs in his voice for even longer than forever.

Divya: Yes, it makes a lot of sense to me that the story and the song would accompany each other. That archives of memory have a cadence is not surprising, but what you’re bringing up here is that family resemblance and genealogy have a kind of borrowed cadence from these musical forms; that the familial story isn’t just a verbal narrative but rather resembles the Qawwali itself— long throaty preambles that lead to improvisations on the same refrain, over and over, multiple voices calling and responding towards increasingly passionate articulation of the tales, until those articulations begin to harmonize toward a synthesis. And, part of this dénouement concerns language, as you and I have discussed— particularly the way inherited languages, mother tongues, become synthesized into contexts for our identities; into nesting places for sentiment.

Pooja: If I sound sentimental, it’s because something about Hindi and Urdu is so beautiful, so melancholic and inherently poetic that an English translation could never do it justice. Every time I listen to these songs, I am so grateful I understand this language that links me back to my past and my grandparents, my sense of personal and collective history. While I understand the language and I can speak it fluently, I cannot read or write in Hindi because I learnt it conversationally. The poems you cite are my very inadequate attempts at articulating my love for it, how it captures home and family for me in a way English ( a language I am better versed in) never can.

The song I cite, in “Listening to Mukesh” is Jaaon Kaha Bata Ae Dil, which literally translates into “Tell me, my heart, where should I go?” and what I love about that song is the twilight loneliness of it. It’s an interesting fact to note, that the lyrics to the song is not in fact written by Mukesh but by Hasrat Jaipuri who was a Hindi and Urdi poet. It was common practice in old Bollywood to have poets be lyricists and for the poets this work would obviously be their largest source of income. It’s little wonder than that the songs and their words tug so hard at my heartstrings because they are poetry.

Divya: It is little wonder. Even now in the Tamil film industry, we have poets like Padmashri Vairamuthu who has collaborated with the Academy Award winning composer A.R. Rahman. Your work is, of course, part of a very long and cross-cultural tradition of the bard, the troubadour (trobairitz, in your case), the carrier of the lyre— could you speak more on how the lyre and the lyric come together for you?

Pooja: How this brought me to my own poetry and music and voice is simply that on some subconscious level I suppose, I’ve never divided poetry and music into two separate things, I’ve always loved the hearing the music of poetry, even if it was the simple music of the human voice. So as a writer, I am drawn to lyrical work, to the music of the line.

The other large force in my poems tends to be nostalgia, which I suppose also runs in my blood. The song I quote in the poem was written in 1959, when my father was a seven year old boy. He’s a romantic at heart. Whenever we visit Bombay, he talks of a simpler time, he points out roads he took to walk to school.

In much the same way, a huge part of me also lives in the past.

The connections between these two poems is also fascinating to me, because I realised them only after I had written both poems years apart. I wrote the Mukesh poem in 2006, and the one about K.L Saigal in 2009, 3 years after my paternal grandfather had passed away.

The song I was listening to when I wrote the K.L Saigal poem was “Jab dil hi toot gaya” The lyrics go “ Jab dil hi toot gaya, hum ji ke kya karenge” which means, “when the heart itself is broken, why go on living” and it felt at the time like I was trying desperately to reach my grandfather by listening to the voice he loved so much because I was so heartbroken at losing him.

I realised the remarkable connection 3 years later in 2012 when writing another poem called “Protocol” that’s in my second collection, where I’ve borrowed the words of another old Hindi song I thought was sung by Saigal , called “Dil Jalta Hain tho Jalne Dei” ( this translates to the opening lines of the poem “if the heart burns, then let it”)

What I didn’t realise when I wrote it was that Mukesh, from my first poem, was such a K.L Saigal fan, that he imitated him in his early songs.

So the song I was in fact thinking was sung by Saigal, was actually sung by Mukesh paying tribute to Saigal. And in much the same way, my dad’s love affair with music harks back to my grandfather’s and both of them I hope will always sing through me so that I can always find my way back home, no matter how far time takes me.

You can listen to Pooja Nansi read the poems featured in this interview.

Pooja Nansi is a poet who believes in the power that performance can lend to the written word. She has published two collections of poetry Stiletto Scars (2007) and Love is an Empty Barstool (2013) , co-edited a poetry anthology of Singaporean Poetry and co-authored a teacher’s resource for Singaporean poetry. She has also participated in poetry projects such as Speechless with the British Council, where she worked in conjunction with poets from London, Ireland, Taiwan, The Philippines, Malaysia and Vietnam and engaged in a month long tour of the UK to explore issues surrounding freedom of speech. Since April 2013, she has been curating a monthly spoken word and poetry event called Speakeasy which has showcased both emerging and established poets from places as diverse as Burma and Botswana. She also runs the Singapore chapter of Burn After Reading. The original London chapter has been run by poet Jacob Sam La Rose since 2011. Burn After Reading is a collective started for young emerging poets (aged 16-24) who are encouraged to write, read, perform and publish as widely as possible. The collective celebrates a diverse range of poetics from 'spoken word' to 'page' and points in between. Since 2009, she has also been one half of the spoken word and music duo The Mango Dollies along with singer-songwriter Anjana Srinivasan. As an educator and writer, she believes strongly in making poetry relevant to the lives of the young people she comes in contact with.

DISCOURSES ON LOCALITY: Singapore